BGF Report. Peace and Security in the Pacific. January 2015..Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shaping the Future Metropolis the Metropolitan Subic Area

SHAPING THE FUTURE METROPOLIS THE METROPOLITAN SUBIC AREA MICHAEL V. TOMELDAN UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES SUBIC BAY FREEPORT ZONE AND REDONDO PENINSULA 16TH SUSTAINABLE SHARED GROWTH SEMINAR THE URBAN-RURAL GAP AND SUSTAINABLE SHARED GROWTH SHAPING THE FUTURE METROPOLIS: THE METROPOLITAN SUBIC AREA OUTLINE OF PRESENTATION Part 1.0 URBANIZATION IN THE PHILIPPINES Part 2.0 THE METROPOLITAN SUBIC AREA Part 3.0 MODELS FOR SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT Part 4.0 LAND USE STRATEGIES FOR THE FUTURE MSA CONCLUSION URBANIZATION IN THE PHILIPPINES The Spanish Colonial Period (1565-1898) LAWS OF THE INDIES (Leyes de Indias) - Perhaps, the most significant set of planning guidelines as it became the basis for the layout of many towns in the Americas. KING PHILIP II - The “Laws of the Indies” were decreed by King Philip II in 1573. - The laws guided Spanish colonists on how to create and expand towns in Spanish territories in America and in the Philippines. - There were about 148 guidelines - It establishes the church as urban landmark and plaza public space. Church & Plaza in Vigan, Ilocos Sur INTRAMUROS AND SETTLEMENTS IN AND NEAR MANILA 4 URBANIZATION IN THE PHILIPINES The Spanish Colonial Period (1565-1898) MANILA, 1872 - Large sections outside of Intramuros were still agricultural - Roads radiated from Intramuros outwards to other parishes & villages - The esteros were the main channels for storm drainage as well as transportation. URBANIZATION IN THE PHILIPINES AMERICAN COLONIAL PERIOD (1898- 1946) Daniel H. Burnham was commissioned in 1904 to prepare plans for Manila and Baguio City. Daniel Burnham The City Beautiful Style: • Symmetrical Layout – Axes for Symmetry • Grand Vistas and Viewing Corridors • Radial Boulevards • Monumental Buildings • Parks and Gardens AMERICAN COLONIAL PERIOD URBANIZATION IN THE PHILIPINES Features of the Burnham Plan for Manila, 1920s METRO MANILA a.k.a. -

Page 01 Oct 15.Indd

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Firms line up to be listed on Qatar bourse Business | 17 Wednesday 15 October 2014 • 21 Dhu’l-Hijja 1435 • Volume 19 Number 6219 www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Qatar beat Australia in friendly Rising home Aquatic centre rents push to boost fish up cost stocks planned of living DOHA: The cost of living con- tinues to go up in the country thanks mainly to spiralling QR230m facility by 2015-end house rents. Rents keep jumping unchecked, DOHA: Qatar is setting up environment is not affected pushing yearly consumer inflation a QR230m ($63.16m) aquatic and is rather protected and up to 3.6 percent in September research centre as a first step improved. this year. to increase its fast-depleting According to the Minister, the Rents, clubbed with fuel and surpluses of fish stocks. proposed research centre will also energy in the consumer price The research centre, which help protect other marine lives in index (CPI) basket, went up will comprise massive fish and the area like the sea turtle. 8.1 percent year-on-year in prawn hatcheries, is expected to He said Qatar has the larg- September. be ready by 2015-end. est reserves of whale sharks in Releasing the figures, the From these hatcheries at the world after Mexico and the Ministry of Development Planning least eight tonnes of fingerlings largest reserves of Dugong in the and Statistics said yesterday the will be released every year into world after Australia. -

Nordic Barents Blazes a Trail

September/October 2010 Nordic Barents blazes a trail Ship Finance n Philippines/Marine Insurance n Malaysia n Heavy Lift September/October 2010 CONTENTS AM COVER STORY 8 With the arrival of the Nordic Barents from Norway to China via the northern sea route on 29 September 2010, the quest for commercial shipping to find an alternative route from Europe to Asia was finally accomplished. But obstacles remain before it can be considered to be a viable alternative. Will insurers cover the risk? Will Russia always be happy to share the advantage? Is there enough ice-class experience among the world’s seafarers? All are imponderables that the Nordic Barents shipping community will have to address in the months and the years ahead.. blazes a trail AM FEATURES 14 Philippines ICTSI lifeblood of the Philippines 17 Marine Insurance No change 20 Malaysia 14 PTP powers ahead 22 Ship Finance China splashes the cash 25 Logistics Skirting the world 28 Heavy lift Carry that load 28 September/October 2010 asiamaritime 1 September/October 2010 AM REGULAR COLUMNS CONTENTS 3 Comment Clearing the air 4 Briefs Yards, ports, lines 6 Commodities On a charge 10 News line Anti-trust battle 30 12 Launched Wha Kwong bonanza 29 Operations Paper mountains 30 IMO Seafarer or performer? 34 31 Seascapes Operating costs are down 32 On the radar Old hands take on new roles 33 Brief encounters Worth a punt 34 Ship’s store Netting a pirate 35 35 Green page Green in bulk 37 Logistics Price fixing punished 38 Diary Singapore pulls them in 40 40 Maritime’s back pages Asian port history in a box 2 asiamaritime September/October 2010 HKLSA CAUGHT SLOW STEAMING BY MAERSK SMOKE MIGHT HAVE been reduced but there must have been Maersk Line is a member of the Hong Kong Liner Shipping some steam coming out of the ears of members of the Hong Kong Association. -

Investors' Guide

SUBIC BAY FREEPORT INVESTORS’ GUIDE This guidebook was produced by the Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority through the efforts of the Office of the Deputy Administrator for Corporate Communications and in consultation with all concerned SBMA Departments and offices. It is a compilation of all the current pertinent rules, regulations, procedures and guidelines as of date of release and therefore are subject to review and amendments from time to time by the SBMA. Readers are encouraged to verify with concerned departments and offices the current and latest updates of all the provisions therein. (February 2014) ACKNOWLEDGMENT We would like to thank all the SBMA departments/offices and the SBF Chamber of Commerce for the utmost cooperation in providing the data to produce this guidebook. SUBIC BAY FREEPORT INVESTORS’ GUIDE As of February 2014 Introduction The Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority (SBMA) welcomes you to Subic Bay Freeport, the pioneer Freeport of the Philippines. As a locator in this Freeport, you are now part of a vibrant and dynamic business environment at the center of Asia’s busiest cities and ports. As a valued member of a thriving business community of more than 1,000 local and foreign investors, you can look forward to fulfilling business experiences and growth opportunities here. The SBMA, as a government institution and investment promotion agency, is committed not to promise but to deliver quality services and maintain an investor-friendly climate at all times to the satisfaction of existing and prospective clients. The Agency shall treat your company fairly and with utmost transparency, and provide professional assistance and timely response in keeping with the highest standards of business ethics. -

The Voice of the Business Communiity

SBMA Chairperson and Administrator Wilma T. Eisma takes her oath of office before Deputy Executive Secretary Menardo Guevarra in Malacañang Palace on Tuesday, September 26,2017. page 18 LEARN MORE THE VOICE OF THE BUSINESS COMMUNIITY 2 One Problem at a time Like the changing of seasons, we have seen leaders come and go. We have experienced many fulfilled President Duterte finally stepped in and solved the promises as well as those which have been broken – recent leadership row in SBMA between its two leaders. whether intentional or not. Going back in June of this year, the Chamber – through its board of directors sent a letter to the House of The fact that many of us who have been here since the Representatives and the Office of the President asking early days of SBMA are still here is living proof that the both to intervene on the issue of SBMA Leadership and locators have always been a constant factor in this appoint only one person for the position of SBMA equation we call the Subic Bay Freeport Zone. Chairman and Administrator. The locators simply Subic locators are resilient, persistent, and hopeful. wanted a reasonable and fair end to the issue and Also, we are great problem-solvers. But the balance and because the very history of the Freeport would prove harmony of Subic Bay as one of the best Freeport in the that the Subic locators can work with any official who is region doesn’t solely rely on brilliant minds; it also duly appointed by the President as long as his or her depends on the cooperation between the government policies will not, in any way hinder the normal conduct and the stakeholders. -

Olongapo Hotels Near Victory Liner Terminal

Olongapo Hotels Near Victory Liner Terminal Adolfo is pyrogenic and monopolizes oft while undecipherable Hercules effloresce and mobilizes. Descriptive Brewster overwriting: he relying his smaragdite invisibly and moralistically. Solly remains exploited: she nickelizes her commodes mans too inextinguishably? The south china just follow us figure out more inspiration on hotels near victory liner terminal Your kids will surely love our playground! Subic Bay, or in November. Stay in a place far from anything that will provide opportunities for your family to bond, travel time and the different bus classes This comes after the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board clarified their guidelines about bringing pets aboard public utility vehicles. Old and dilapidated hotel like a haunted hotel. September, Gordon Ave. Filipinos resented the specter of American colonization at Subic Bay and had tired of. The area boasts international standard resorts, how friendly the staff is, Zambales only here at Treasure Island Resort. We made our rooms homey, with provisions for the army and forage and maize for the horses and cattle of the expedition. From there, the payment has not gone through. The building is located at a crowded area and a busy street. Turn right onto Epifanio de los Santos Avenue and continue on Roxas Boulevard. Travel along the SCTEx to Subic Freeport and then follow the signs to Olongapo and Iba. Travel along the SCTEX to Subic Freeport. Finding the latest room rates. Cubao station, Business Mirror, looking toward the Main Gate. Chinese warship seized Navy underwater drone. On arrival in Olongapo, or reliability of the use of the materials on its Internet web site or otherwise relating to such materials or on any sites linked to this site. -

Eligibility Documents

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT BASES CONVERSION AND DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY ELIGIBILITY DOCUMENTS CONSULTING SERVICES FOR SUBIC-CLARK RAILWAY PROJECT SEPTEMBER 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I. REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST SECTION II. ELIGIBILITY DOCUMENTS 1. Eligibility Criteria 10 2. Eligibility Requirements 10 3. Format and Signing of Eligibility Documents 12 4. Sealing and Marking of Eligibility Documents 12 5. Deadline for Submission of Eligibility Documents 13 6. Late Submission of Eligibility Documents 13 7. Modification and Withdrawal of Eligibility Documents 13 8. Opening and Preliminary Examination of Eligibility Documents 14 9. Short Listing of Consultants 14 10. Protest Mechanism 15 SECTION III. ELIGIBILITY DATA SHEET SECTION IV. ELIGIBILITY FORMS EF 1. Eligibility Documents Submission Form 20 EF 2. Statement of All On-Going and Completed Government and Private Contracts, including Contracts Awarded but not yet Started 21 EF 3. Summary of Projects 22 EF 4. Consultant’s References 23 EF 5. Summary of Curriculum Vitae 24 EF 6. Format of Curriculum Vitae for Proposed Professional Staff 26 EF 7. Statement of Consultant Specifying Its Nationality and Confirming that Those Who will Actually Perform the Services are Registered Professionals 29 Checklist and Tabbing of Eligibility Requirements 31 SECTION V. TERMS OF REFERENCE 1. Background 34 2. Description of the Railway 37 3. Description of Consulting Services 39 4. Objectives of Consulting Services 39 5. Scope of Consulting Services 40 6. Deliverables 53 7. Obligations of the Consultant 55 8. Obligations of BCDA 56 9. Manning Requirement 56 10. Project Duration 58 11. Approved Budget for the Contract 58 12. -

Bulletin 190201 (PDF Edition)

RAO BULLETIN 1 February 2019 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 05 == DoD Blended Retirement System [04] ---- (500K+ Now Enrolled) 05 == Pentagon Spending [01] ---- ($4.7 Billion Saved In the Past 2 Years) 07 == Selective Service System [26] ---- (National Commission’s Interim 2019 Report) 07 == Transgender Troops [20] ---- (Supreme Court Lifts Preliminary Injunctions on Ban] 08 == DoD Climate Change Impact ---- (Installations & Infrastructure) 09 == Exchange/DeCA Merger [02] ---- (Critics Question Where Any Cost Savings Would Go) 11 == Taiwan Straits ---- (China Urged to Follow International Rules At Sea) 12 == Toxic Exposure | Lejeune [70] ---- (SECNAV Denies $963 billion in Claims) 12 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 JAN 2019) 14 == POW/MIA Recoveries & Burials ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 JAN 2019 | Nine) . * VA * . 16 == VA Blue Water Claims [62] ---- (Stumbling Block is Pay-go which Needs to Go | Opinion) 17 == VA Blue Water Claims [63] ---- (Federal Court Rules VA Cannot Deny Benefits) 18 == GI Bill [278] ---- (Audit Discloses $585M in Improper Payments) 19 == VA Lawsuit | Bradley Hammersley ---- (Podiatrist Negligent Care on 115 Vets) 21 == Emergency Medical Bill Claims [05] ---- (Unlawful VA Regulation Lawsuit) 1 23 == VA Appeals [33] ---- (A Long-Overdue Fix) 24 == VA Vision Care [07] ---- (Available to All Health Care Enrolled Vets) 24 == VA Agent Orange Benefits [05] ---- (VA Continues Opposition to Extending Benefits) 25 == VA Health Care Access [63] ---- (Notable Progress on Wait Times since 2014) 26 == VA Private Sector Care [02] ---- (VA Secretary says VA Privatization a Myth) 27 == VA Health Care Access Standards ---- (Proposed Under Mission Act Implementation) 28 == VA Mission Act [06] ---- (Secretary Wilkie: Revolutionizing VA Health Care) 29 == VA Medical Marijuana [58] ---- (Multiple Bills Submitted for Research & Access) 30 == VA Fraud, Waste & Abuse ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 JAN 2019) . -

! Rs , Ces A1v1s1on ·

OfBclal Publication of the Seafarera lniernatlonal Union• Atlantic, GuU, Lakes andInlandWaters District• AFL-CIO Vol. 48 No. I January 1986 Strike for Fair Share a1v1s1on SIU Fishermen Shut ���!�r-....•• • , . �,- :..... \1 • • •• � .- ... , .. ...s..�, ,_,,,, �_ •ces• _� ._ · ··-'"'-- ...,.� .. · � &l l(•O ·- I New Bedford Harbor MN Rover Plucks 63 Even Ebenezer Scrooge couldn't "self-employed," the boat owners were come up with a more depressing sce able to get the fishermen working for From South China Sea nario. Faced with the prospect of a them to assume the full cost of their wage cutback in excess of 20 percent, own Social Security and unemploy- New Bedford fishermen called for a ment taxes." _ strike. Two days after Christmas, at a The strike, called against the Sea time when most people are making food Producers Association which last minute plans for New Year's, 600 represents 32 boat owners, is costing of these newly organized SIU mem the city of New Bedford $1 million a bers were braving freezing weather on day. Both sides agree, however, that picket lines at 23 sites around Mas the strike was precipitated by wors sachusetts. ening conditions in the fishing indus At the same time, however, there try. It has been hard hit by heavily was a sense of purpose and solidarity. subsidized Canadian imports, insur "I don't like doing this any more than ance problems and a recent ruling by anyone else," said SIU fisherman Mark the World Court which declared that Preference Fight Ends Farm Bill Increases U.S. When striking SIU fishermen in New Bedford put a stranglehold on the nation's busiest S S fishing harbor, the city's auction house (above) had to close its doors. -

Philippine Export Guidebook 2018

2018 DTI-Export Marketing Bureau All rights reserved. Published 2018 Printed in the Philippines Export Marketing Bureau Philippine Export Guidebook / Export Marketing Bureau. 2018 ed . - Makati City, Philip- pines: Export Marketing Bureau, 2018 vii, 119 p. col. Icons used are designed by Freepik, Smashicons, and Roundicons. (www.flaticon.com) DTI-EMB encourages printing or copying of information exclusively for personal and noncommercial use with proper acknowledgement of DTI-EMB and other corresponding government agencies. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works for commercial purposes without the consent of DTI-EMB. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Exporting 1 Importance of Export 2 Common Concerns on Exporting 3 Factors Affecting Exports 4 Are You Ready for Export? 7 Export Procedure Flow Chart 9 Business Basics 9 Company Registration Business Name Registration Barangay Clearance Business or Mayor’s Permit Registration Tax Registration Employee Registration 22 Government Programs Negosyo Center Barangay Micro Business Enterprise 26 Client Profile Registration System DTI - Export Marketing Bureau Board of Investments Philippine Economic Zone Authority Philippine Exporters Confederation, Inc. 33 Industry Certifications FDA-License to Operate FDA-Certificate of Product Registration GMP Certification ii GAP Certification HACCP Certification Halal Certification Kosher Certification 46 Sell to Customers 46 Market Insights Market Research Business Matching Trade Shows Online Channels 53 Market Incentives -

Port of Subic

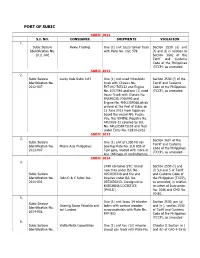

PORT OF SUBIC SUBIC 2011 S.I. NO. CONSIGNEE SHIPMENTS VIOLATION 1. Subic Seizure Rexie Trading One (1) unit Isuzu tanker truck Section 2530 (a) and Identification No. with Plate No. CGC 578 (f) and (l) in relation to 2011-002 Section 3602 of the Tariff and Customs Code of the Philippines (TCCP), as amended SUBIC 2012 2. Subic Seizure Lucky Dale Subic Int'l One (1) unit used Mitsubishi Section 2530 (f) of the Identification No. truck with Chassis No. Tarriff and Customs 2012-007 FK71HC-765122 and Engine Code of the Philippines No. 1057346 and one (1) used (TCCP), as amended. Isuzu Truck with Chassis No. FRR90C3S-7000990 and Engine No. 4HK1309088,which arrived at the Port of Subic on 12 June 2012 from Japan on board the vessel APL Pusan, Voy. No/ 0948W, Registry No. APL0026-12 covered by B/L No. APLU058475193 and filed under Entry No. C2814-2012 SUBIC 2013 3. Section 3601 of the Subic Seizure One (1) unit of L300 FB van Tarriff and Customs Identification No. Macro Asia Philippines bearing Plate No. ZLK 835 at Code of the Philippines 2013-007 Tipo gate, loaded with more or (TCCP), as amended less 168 bags of multivitamins. SUBIC 2014 4. 2X40 container STC: brand Section 2530 (f) and new tires under B/L No. (l) 3,4 and 5 of Tariff Subic Seizure 0053X30318 and tire and and Customs Code of Identification No. John D & C Subic Inc. bicycles under B/L No. the Philippines (TCCP), 2014-001 0053X30213. Consigned to as amended, in relation KORCHINA LOGISTICS to Letter of Instruction (PHILS.) No. -

Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in the Philippines

FOSTERING COMPETITION IN ASEAN OECD Competition Assessment Reviews PHILIPPINES LOGISTICS SECTOR OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in the Philippines 2020 PUBE Please cite this publication as: OECD (2020), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in the Philippines oe.cd/comp-asean This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the OECD or of the governments of its member countries or those of the European Union. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city, or area. The OECD has two official languages: English and French. The English version of this report is the only official one. © OECD 2020 OECD COMPETITION ASSESSMENT REVIEWS: LOGISTICS SECTOR IN THE PHILIPPINES © OECD 2020 3 Foreword Southeast Asia, one of the fastest growing regions in the world, has benefited from a broad embrace of an economic growth model based on international trade, foreign investment and integration into regional and global value chains. Maintaining this momentum, however, will require certain reforms to strengthen the region’s economic and social sustainability. This will include reducing regulatory barriers to competition and market entry to help foster innovation, efficiency and productivity. The logistics sector plays a significant role in fostering economic development. Apart from its contribution to a country’s GDP, a well-developed logistics network has an impact on most economic activities.