Cohors I Aelia Dacorum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coin Hoards from the British Isles 2015

COIN HOARDS FROM THE BRITISH ISLES 2015 EDITED BY RICHARD ABDY, MARTIN ALLEN AND JOHN NAYLOR BETWEEN 1975 and 1985 the Royal Numismatic Society published summaries of coin hoards from the British Isles and elsewhere in its serial publication Coin Hoards, and in 1994 this was revived as a separate section in the Numismatic Chronicle. In recent years the listing of finds from England, Wales and Northern Ireland in Coin Hoards was principally derived from reports originally prepared for publication in the Treasure Annual Report, but the last hoards published in this form were those reported under the 1996 Treasure Act in 2008. In 2012 it was decided to publish summaries of hoards from England, Wales, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and the Channel Islands in the British Numismatic Journal on an annual basis. The hoards are listed in two sections, with the first section consisting of summaries of Roman hoards, and the second section providing more concise summaries of medieval and post-medieval hoards. In both sections the summaries include the place of finding, the date(s) of discovery, the suggested date(s) of deposition, and the number allocated to the hoard when it was reported under the terms of the Treasure Act (in England and Wales) or the laws of Treasure Trove (in Scotland). For reasons of space names of finders are omitted from the sum- mary of medieval and post-medieval hoards. Reports on most of the English and Welsh hoards listed are available online from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) website: select the ‘Search our database’ bar under finds.org.uk/database, and type in the treasure case number without spaces (e.g. -

Roman Britain in the Third Century AD

Roman Britain in the third century AD Despite Claudius’s invasion of Britain in AD 43, the population was still largely British with the local administrative capital at Venta Belgarum - now Winchester. By the 3rd century there was political unrest across the Roman Empire, with a rapid succession of rulers and usurpers. Some were in power for only a few months before being killed by rivals or during wars, or dying from disease. The situation became even more unstable in AD 260 when Postumus, who was Governor of Lower Germany, rebelled against the central rule of Rome and set up the breakaway Gallic Empire. For the next 14 years the Central and Gallic Empires were ruled separately and issued their own coinage. Despite the turmoil in the Empire as a whole, Britain appears to have experienced a period of peace and prosperity. More villas were built, for example, and there is little evidence of the barbarian raids that ravaged other parts of the Empire. Map showing the Gallic and Central Empires, courtesy of Merritt Cartographic 1 The Boldre Hoard The Boldre Hoard contains 1,608 coins, dating from AD 249 to 276 and issued by 12 different emperors. The coins are all radiates, so-called because of the radiate crown worn by the emperors they depict. Although silver, the coins contain so little of that metal (sometimes only 1%) that they appear bronze. Many of the coins in the Boldre Hoard are extremely common, but some unusual examples are also present. There are three coins of Marius, for example, which are scarce in Britain as he ruled the Gallic Empire for just 12 weeks in AD 269. -

Siegfried Found: Decoding the Nibelungen Period

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (Gdańsk, February 2018) SIEGFRIED FOUND: DECODING THE NIBELUNGEN PERIOD CONTENTS I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? 2 II Siegfried the Dragon Slayer and the Dragon Legion of Victorinus 12 III Time of the Nibelungen. How many migration periods occurred in the 1st millennium? Who was Clovis, first King of France? 20 IV Results 34 V Bibliography 40 Acknowledgements 41 VICTORINUS (coin portrait) 2 I Was Emperor VICTORINUS the historical model for SIEGFRIED of the Nibelungen Saga? The mythical figure of Siegfried from Xanten (Colonia Ulpia Traiana), the greatest hero of the Germanic and Nordic sagas, is based on the real Gallic emperor Victorinus (meaning “the victorious”), whose name can be translated into Siegfried (Sigurd etc.), which means “victorious” in German and the Scandinavian languages. The reign of Victorinus is conventionally dated 269-271 AD. He is one of the leaders of the so-called Gallic Empire (Imperium Galliarum; 260-274 AD), mostly known from Historia Augusta (Thayer 2018), Epitome de Caesaribus of Aurelius Victor (Banchich 2009), and the Breviarum of Eutropius (Watson 1886). The capital city of this empire was Cologne, 80 km south of Xanten. Trier and Lyon were additional administrative centers. This sub-kingdom tried to defend the western part of the Roman Empire against invaders who were taking advantage of the so-called Crisis of the Third Century, which mysteriously lasted exactly 50 years (234 to 284 AD). Yet, the Gallic Empire also had separatist tendencies and sought to become independent from Rome. The bold claim of Victorinus = Siegfried was put forward, in 1841, by A. -

THE FRACTURE of IMPERIAL ROME the Rise and Fall of the Gallic Empire 260-274 CE a Set of Eight Bronze Coins

THE FRACTURE OF IMPERIAL ROME The Rise and Fall of the Gallic Empire 260-274 CE A Set of Eight Bronze Coins Coin type and grade may vary Order code: 8GALLICEMPBOX somewhat from image Beginning with the reign of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE, the Roman Empire enjoyed two full centuries of peace and prosperity. The Pax Romana was unprecedented in both duration and territory—at its height, Rome controlled the entire Mediterranean region: most of Europe, including Britannia; all of North Africa from Gibraltar to Egypt; and a vast swath of the Middle East stretching into Mesopotamia and the Caucasus. Governing that many diverse populations so effectively, and for so long, is a feat unrivaled in the annals of history. To do so, the Romans established the most efficient system of administration the world had ever known. Career bureaucrats—prefects, politicians, tax collectors—maintained the system regardless of who was seated on the throne. During the Pax Romana, Rome also boasted a series of strong, stable emperors. Although there were periods of unrest, these tended to be short. After the death of Nero, three family dynasties provided the Empire with a consistent succession of emperors. By the third century CE, the empire began to show signs of collapse. A parade of emperors took the throne, mostly from the ranks of the military. Years of civil war and open revolt led to an erosion of territory. In the year 260, in a battle on the Eastern front, the Emperor Valerian was taken prisoner by the hated Persians. He died in captivity, and his corpse was stuffed and hung on the wall of the palace of the Persian king. -

On the Roman Frontier1

Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Impact of Empire Roman Empire, c. 200 B.C.–A.D. 476 Edited by Olivier Hekster (Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Lukas de Blois Angelos Chaniotis Ségolène Demougin Olivier Hekster Gerda de Kleijn Luuk de Ligt Elio Lo Cascio Michael Peachin John Rich Christian Witschel VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/imem Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016036673 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1572-0500 isbn 978-90-04-32561-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32675-0 (e-book) Copyright 2016 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Stoke Lyne Coin Hoards and the Roman Crisis of the Third Century

Stoke Lyne coin hoards and the Roman Crisis of the Third Century Oxfordshire Museum and Oxfordshire Museum Services are pursuing the possible acquisition of two Roman coin hoards found by a metal detectorist in 2016 near Stoke Lyne (near Bicester). The total number of coins in the hoards is approximately 2200 and the majority of the coins date from the late third century AD. The earliest coins have a higher silver content but the bulk of the hoard is made up of a debased copper alloy coinage. The earliest coins would seem have been struck between 271 AD and 284 AD. The coins are not of high commercial value but help to consolidate and extend our knowledge of the Roman presence in North Oxfordshire. The coins in the hoards were struck in one of the most chaotic periods of the later Roman Empire. The Roman period, 235 - 284 AD, has been called, by later historians, ‘The Crisis of the Third Century’. For a short time, the Empire became ungovernable as a single unit and split into three components under three or more different leaders and warlords. After this short period of instability, the Empire was temporarily re-united under Aurelian (284 AD) and then formally split by Diocletian (293 AD) into a Western half to be centred on Rome and an Eastern half to be centred on Nicomedia and other eastern cities. Simply put, the Empire had become too big with too huge borders to be governed centrally from Rome in an age of increasing barbarian activity and economic complexity. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/02/2021 01:07:49PM Via Free Access MAPPING the CRISIS of the THIRD CENTURY

EPILOGUE John Nicols - 9789047420903 Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 01:07:49PM via free access MAPPING THE CRISIS OF THE THIRD CENTURY John Nicols The Greek philosopher and sophist Protagoras would surely not mind this reuse of one of his most famous statements. “Concerning the crisis of the third century, I have no means of knowing whether there was one or not, or of what sort of a crisis it may have been. Many things prevent knowledge including the obscurity of the subject and the brevity of human life.”1 Within these proceedings one nds striking disagreement about whether there was a crisis as the term has been conventionally understood. And, if there was one, when did it begin? Dictionaries de ne our word crisis as: “An unstable condition, as in political, social, or economic affairs, involving an impending abrupt or decisive change”. During the years 235 to 285, the Roman Empire surely did enter a period of instability. The patterns of ‘emperor mak- ing and breaking’ and of barbarian invasion during this period mark in my estimation the characteristics of a major political crisis. Indeed, when one compares the overall stability of the Roman imperial system and government of the mid-second to that of the mid-third century, the differences are readily apparent both in terms of leadership and defense.2 In sum, that there was a ‘crisis’ is a fundamental assumption of this paper; but it is also a demonstrable proposition. I am moreover especially concerned here not only how to understand the nature of the crisis as a complex set of related events, but also how to explain the complexities of the crisis to others, especially to students. -

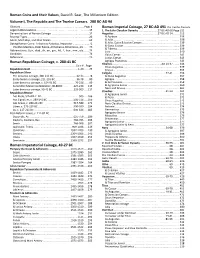

Roman Coins and Their Values, David R. Sear, the Millenium

Roman Coins and their Values , David R. Sear, The Millenium Edition Volume I, The Republic and The Twelve Caesars. 280 BC-AD 96 Glossary ........................................................................ ............ Page 8 Roman Imperial Coinage, 27 BC-AD 491 The Twelve Caesars Legend Abbreviations ................................................... ................... 15 1. The Julio-Claudian Dynasty .........................27 BC-AD 68 . Page 311 Denominations of Roman Coinage .............................. ................... 17 Augustus ...........................................................27 BC-AD 14 ......... 312 Reverse Types ............................................................... ................... 26 & Agrippa ......................................................................... ......... 336 Mints, Mint Map, and Mint Marks................................ ................... 65 & Julia ............................................................................... ......... 338 Dating Roman Coins: Tribunicia Potestas, Imperator .. ................... 72 & Julia, Gaius & Lucius Caesars ........................................ ......... 339 Pontifex Maximus, Pater Patrae, Armeniacus, Britannicus, etc. ....... 73 & Gaius Caesar ................................................................. ......... 339 & Tiberius ......................................................................... ......... 339 Abbreviations: Cuir., diad., dr., ex., gm., hd., l., laur., mm., etc ........ 74 Livia ................................................................................. -

Recent Finds of Roman Coins in Lancashire: Third Report

RECENT FINDS OF ROMAN COINS IN LANCASHIRE: THIRD REPORT David Shatter Since the publication of my last note in these Transactions (Shotter 1994), the Centre for North-West Regional Studies at Lancaster University has published a First supplement (1995) to my Roman coins from north-west England (1990); this included all coin-finds from the county that had been notified up to October 1994. The present note, therefore, takes up from that point to include finds that have been reported since then, together with fresh information on finds already recorded. HOARDS 1. BORWICK (MANOR FARM). More details have come to light regarding a hoard which was found in 1993, but of which little information was initially available (Shotter 1995, p. 52). It is now known that the hoard consisted of approximately fifty coins, which have been distributed amongst various parties. Sixteen of these have been presented for examination, most of which have been poorly preserved and are very worn, not surprising in view of the fact that the latest coin was an issue of Julia Domna. The sixteen coins are: Vespasian 1 (as) Domitian 1 (sestertius) Hadrian 6 (4 sestertii, inc. R.I.C. 586, 596; dupondius; as) Antoninus Pius 1 (as) 198 David Shatter Faustina I 3 (2 sestertii, inc. R.I.C. (Antoninus) 1139; dupondius) Marcus Aurelius 1 (sestertius) Faustina II 1 (sestertius) Septimus Severus 1 (dupondius) Julia Domna 1 (sestertius, R.I.C. 859) Contrary to the earlier report, a denarius (an issue of Antoninus Pius) did not belong to the hoard (see below, casual find 2). -

Ancient Coin Reference Guide

Ancient Coin Reference Guide Part One Compiled by Ron Rutkowsky When I first began collecting ancient coins I started to put together a guide which would help me to identify them and to learn more about their history. Over the years this has developed into several notebooks filled with what I felt would be useful information. My plan now is to make all this information available to other collectors of ancient coinage. I cannot claim any credit for this information; it has all come from many sources including the internet. Throughout this reference I use the old era terms of BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domni, year of our Lord) rather than the more politically correct BCE (Before the Christian era) and CE (Christian era). Rome With most collections, there must be a starting point. Mine was with Roman coinage. The history of Rome is a subject that we all learned about in school. From Julius Caesar, Marc Anthony, to Constantine the Great and the fall of the empire in the late 5th century AD. Rome first came into being around the year 753 BC, when it was ruled under noble families that descended from the Etruscans. During those early days, it was ruled by kings. Later the Republic ruled by a Senate headed by a Consul whose term of office was one year replaced the kingdom. The Senate lasted until Julius Caesar took over as a dictator in 47 BC and was murdered on March 15, 44 BC. I will skip over the years until 27 BC when Octavian (Augustus) ended the Republic and the Roman Empire was formed making him the first emperor. -

This Remarkable Collection of Genuine Coins

This remarkable collection of genuine coins traces the history of the Empire from the late second through the fourth centuries, a period of tumult and uncertainty, when emperors came and went, almost none of them dying of natural causes. The Roman Empire was the greatest the world had ever known. Its dominions stretched from Britain to Persia, from the Maghreb to Northern Europe, and encompassed every inch of shoreline along the great Mediterranean Sea. While Rome endured for centuries, establishing a system of colonization and administration that is still copied today, the Empire was always on the brink of collapse. Indeed, the definitive history of Rome, Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, covers the period from 98 through 1590 CE. In other words, Rome’s decline and fall lasted for almost 15 centuries! This remarkable collection of genuine bronze coins traces the history of the Empire from the late second through the fourth centuries, a period of tumult and uncertainty, when emperors came and went, almost none of them dying of natural causes. Indeed, the entire history of the Roman Empire is revealed in its coinage. Coins were the newspapers of their day, used not only to exchange for goods and services, but to share information. The portraits, legends, and reverse iconographies describe the adoration of the emperors and their heirs and families, and communicate imperial agendas in the realms of politics, religion, domestic life and the military. All of this history is handed down to us on these ancient coins. 1. -

Roma Secunda Trier in Late Antiquity

Hans-Peter Kuhnen Roma Secunda Trier in Late Antiquity When writing on Trier�s Roman past modern historians, since the early nineteenth century, followed almost exclusively the ancient writers in viewing the late Ro- man period as an age of military defeat and economic decline, ending with catastrophic destructions of ancient city life. Archaeology however, in the last few decades, has in vain looked for wide spread destruc- tion layers to be connected with Germanic invasions in the fourth and fifth centuries. Instead, the excavators found indications of an undisturbed transformation process between the ancient and the medieval city, thus establishing archaeology as an independent source of historical information. Trier: a late Roman metropolis Trier�s history as an Imperial centre started in the later third century: after an agricultural and economic boom of more than two centuries, the city became, together with Cologne, one of the capitals of the Gallic Empire. Between 260 and 274 A.D. the city issued coins bearing the portraits of the usurpators Postumus, Victorinus Tetricus I and Tetricus II who claimed to be Emperors of the Gaulish and Germanic provinces of the Roman Empire.1 Twelve years after the suppression of the usurpation by Empe- ror Aurelian in 274 A.D. Trier was chosen as residence by Maximianus, Diocletian�s colleague in the Tetrarchy. In 293/4 A.D. an Imperial mint was opened in the Mosella capital, and from 306 to 315 A.D., in succession of 1 K.J. Gilles, Das Münzkabinett im Rheinischen Landesmuseum Trier. Ein Überblick zur trierischen Münzgeschichte (Trier 1996) 22f.