God's Blessed Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Women's Heritage Trail

MARYLAND WOMEN’S HERITAGE TRAIL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 101112131415161718192021 A A ALLEGANY COUNTY WASHINGTON COUNTY CECIL COUNTY GARRETT COUNTY CARROLL COUNTY HARFORD COUNTY B B BALTIMORE COUNTY FREDERICK COUNTY C C BALTIMORE CITY KENT COUNTY D ollowollow thethe footstepsfootsteps HOWARD COUNTY D ollow the footsteps and wander the paths where in Southern Maryland, to scientists, artists, writers, FMaryland women have built our State through- educators, athletes, civic, business and religious MONTGOMERY COUNTY F QUEEN ANNE’S out history. Follow this trail of tales and learn about leaders in every region and community. Visit these ANNE ARUNDEL E COUNTY E the contributions made by women of diverse back- sites and learn about women’s accomplishments. COUNTY grounds throughout Maryland – from waterwomen Follow in the footsteps of inspirational Maryland on the Eastern Shore to craftswomen of Western women and honor our grandmothers, mothers, Maryland, to civil rights activists of Baltimore and aunts, cousins, daughters and sisters whose contri- F Central Maryland, to women who worked the land butions have shaped our history. F Washington D.C. TALBOT WESTERN MARYLAND REGION PRINCE GEORGE’S COUNTY ALLEGANY COUNTY Anna Eleanor Roosevelt Memorial Tree COUNTY CAROLINE G Chesapeake and Ohio (C&0) Canal National Historic Park Gladys Noon Spellman Parkway COUNTY G Jane Frazier House Adele H. Stamp Student Union Elizabeth Tasker Lowndes Home Mary Surratt House The Woodyard Archeological Site FREDERICK COUNTY CALVERT H Beatty-Creamer House H Nancy Crouse House CENTRAL MARYLAND REGION CHARLES COUNTY COUNTY Barbara Fritchie Home ANNE ARUNDEL COUNTY Hood College Annapolis High School Ladiesburg Banneker-Douglass Museum National Museum of Civil War Medicine DORCHESTER COUNTY Charles Carroll House of Annapolis National Shrine of Elizabeth Ann Seton Chase-Lloyd House Helen Smith House and Studio I Coffee House I Steiner House/Home of the WICOMICO COUNTY Government House Frederick Women’s Civic Club ST. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

Manual of the Legislature of New Jersey

STATE OF NEW JERSEY FITZGERALD & GOSSON West Ena. x^^^.a Street, SO^ER'^ILLE, .V. J. N. B. BICHAHDSON, GROCERIES AND PROVISIONr West End. Main Street, SOMERl/ILLE, f^. J, r ^(?^ Sfeabe ©i j^ew JeF^ey. MUNUSL ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTH SESSION ^^"^^^ ^^^aRY NEW j: 185 W. ^^t^ £.Lreet Trei COPYRIGHT SECURED. TRENTON, N. J.: Compiled fkom Official Documents and Careful Reseakch, by FITZGERALD & GOSSON, Legislative Reporters. Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1883, by THOMAS F. FITZGERALD AND LOUIS C. GOSSON, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. >§®=" The newspaper press are welcome to use such parts of the work as they may desire, on giving credit therefor to the Manual. INTRODUCTORY THE INIanual of the One Hundred and Eighth Session of the Legislature of New Jersey is, we trust, an improvement on preceding volumes. We have honestly striven every year to make each succeeding book suj^e- rior to all others, and hope, ere long, to present a work which will take rank with the best of its kind published in the United States. To do this we need a continuance of the support heretofore given us, and the official assist- ance of the Legislature. We are confident that this little hand-book, furnished at the small cost of one dollar a volume, is indispensable to every legislator, State official and others, who can, at a moment's notice, refer to it for information of any sort connected with the politics and affairs of State. The vast amount of data, compiled in such a remarkably concise manner, is the result of care- ful research of official documents; and the sketches of the Governor, members of the Judiciary, Congressmen, members of the Legislature, and State officers, are authentic. -

CHALLENGING the EXCLUSIVE PAST 16 - 19 March 2016 // Baltimore, Maryland

// CHALLENGING THE EXCLUSIVE PAST 16 - 19 March 2016 // Baltimore, Maryland A Joint Annual Meeting of the National Council on Public History and the Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, Image ID# B64-9 (top) and ID# PP177-101A Society for History in the Federal Government (bottom). RENAISSANCE BALTIMORE HARBORPLACE HOTEL A Joint Annual Meeting of the National Council on Public History and the Society for History in the Federal Government 16-19 March 2016 Renaissance Baltimore Harborplace Hotel Baltimore, MD Picketers outside Ford’s Theatre in Baltimore. Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Tweet using #ncph2016 Society, Image ID# HEN-00-A2-178. CONTENTS Schedule at a Glance .............................. 2 Registration ................................................ 5 Hotel Information ...................................... 5 Travel Information .................................... 6 History of Baltimore ..................................7 Tours and Field Trips ..............................14 Special Events ..........................................16 Workshops ...............................................20 Conference Program .............................23 Index of Presenters ................................42 NCPH Committees .................................44 Registration Form ...................................59 2016 PROGRAM COMMITTEE MEMBERS Gregory Smoak, The American West Center, University of Utah (Chair) Carl Ashley, U.S. Department of State (Co-Chair) Kristin Ahlberg, U.S. Department of State Michelle Antenesse Laurie -

Nunc Pro Tunc

THE UNITED STATES Fall 2016 DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSE Y HISTORICAL SOCIETY NUNC PRO TUNC Inside this Issue: Honoring Our Chiefs Chief Judge Simandle Receives the AFBNJ’s 2016 Brennan Award Portrait Unveiling: The Hon. Garrett E. Brown, Jr. An Exhibit: The Addonizio Trial Trenton Courthouse Jury Room Dedication: The Hon. Anne E. Thompson Remembering: Edgar Y. Dobbins Hon. Jerome B. Simandle Hon. Garrett E. Brown, Jr. The D.N.J.’s First Chief Probation Officer By Wilfredo Torres Celebrating: The 225th Anniversary of the D.N.J. U.S. Attorney’s Office By Mikie Sherrill, Esq. Remembering: Selma, Alabama and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 By Andrea Lewis-Walker 2015 Clarkson S. Fisher Hon. John W. Bissell Hon. Anne E. Thompson Award-Winning Essay: “Taste Tells” ____________________________________________________ By Gregory Mortensen, Esq. Recently our Court’s current and three previous Chief Judges have been honored in various ways for their extraordinary On Behalf of The Historical Society: service to the people of New Jersey — including, for two of Patrick J. Murphy III, Esq. them, having played critical roles as assistant federal prosecutors Editor in a watershed conviction with national impact and historic import. Herein, the Historical Society showcases those honors. NUNC PRO TUNC Page 2 Chief Judge Jerome B. Simandle Receives the AFBNJ’s 2016 Brennan Award On the evening of June 16, 2016, the As- sociation of the Federal Bar of New Jersey be- stowed the William J. Brennan, Jr. Award, its highest honor, upon New Jersey’s two top ju- rists: D.N.J. -

HISTORY of ROCKAWAY TOWNSHIP by JAMES H. NEIGHBOUR. THIS Township Lies in the Northeastern Part of the County and Embraces More

HISTORY OF ROCKAWAY TOWNSHIP BY JAMES H. NEIGHBOUR. THIS township lies in the northeastern part of the county and embraces more territory by over 3,000 acres than any other township in the county. Its length from Newfoundland to Shongum is about twenty miles, and its width from Powerville to the Jefferson township line near Luxemburg is about twelve miles. It was erected in 1844 from parts of Pequannock and Hanover townships, by an act of the Legislature, and made the eleventh township in the county. The principal part was taken from Pequannock, or from "Old Pequannock" as it is frequently called because Pequannock has existed since the year 1740 as a separate and distinct township. The history of Rockaway township prior to 1844 will naturally apply to those parts of Pequannock and Hanover up to that date. This township was settled principally by the Hollanders; at least there were many families of that nationality in the lower or eastern part of the township, who came there about 1715. In the act of 1844 creating the township of Rockaway the boundaries are given as follows: "Beginning at the bridge over the Pequannock River, at Charlottenburg iron works, and thence running a straight line to the north end of the county bridge first above Elijah D. Scott’s forge at Powerville; and to include all that part of Hanover that may lie to the north and west of said line; thence a straight line to the center of the natural pond in Parsippany woods called Green’s Pond; thence a straight line to the corner of the townships of Morris, Hanover and -

BMI Membership Benefits

BMI Membership Benefits • Unlimited daily admission for one year • 10% off in BMI Gift Shop • Free access to archives & 10% off photocopies • 10% off birthday party packages • Advance notice of exhibit openings • Invitations & reduced rates to BMI events/programs • The Production Line weekly online newsletter • Members-Only monthly online newsletter • Invitations to BMI Member-only events & special offers • Discounts to area attractions* • Discounts at select restaurants (present your membership card to server): HarborQue, 1125 S. Charles Street Mother’s Federal Hill Grille, 1113 S. Charles Street Hull Street Blues, 1222 Hull Street LP Steamers, 1100 E Fort Avenue Regi’s Bistro, 1002 Light Street Membership Levels Individual $35, Senior (62+) $25 Membership privileges for one individual Household $55 [MOST POPULAR] Two adults & up to 6 children/grandchildren under 18 Four one-time use museum passes Membership Listed Below Include: Reciprocal admission to local and national museums* 20% off admission for two people per visit Anchor $100 Two adults & up to 6 children/grandchildren under 18 Six one-time use museum passes Crane $120 [GREAT VALUE] Four adults & up to 6 children/grandchildren under 18 Eight one-time use museum passes Two membership cards Generator $250 Four adults & up to 6 children/grandchildren under 18 Ten one-time use museum passes Propeller $500 Four adults & up to 6 children/grandchildren under 18 Ten one-time use museum passes Opportunity for private tour *Discount information can be found at www.thebmi.org (Continues >>>) Hours: Open Tuesday – Sunday 10 a.m. – 4 p.m. Closed: Mondays, Memorial Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day Free Parking! 1415 Key Highway, Inner Harbor South, Baltimore, MD 21230 410-727-4808/www.thebmi.org Reciprocal Admission Programs GREATER BALTIMORE HISTORY ALLIANCE BMI Members who join at $100 or more enjoy free general admission at 41 participating museums. -

Manual of the Legislature of New Jersey

r Date Due T— ^ J328 Copy 3 M29i| N. J. :ianual of the Legisla- ture of New Jersey 1891 J328 Copy 3 M29U N. J. Manual of the Legis- lature of Uei'j Jersey 1691 DATE DUE BORROWER'S NAME New Jersey State Library Department of Education Trenton, New Jersey 08625 Ifc^V^3^^>K~•#tW>'>0-' =• LEON ABBETT, Governor. STATE OF NEW JERSEY. MANUAL f egislature of New Jersey Compliments of T. F. FITZGERALD, Publisher. SSION, 1891 S2>Si% CU7^3 BY AUTHORITY OF THE LEGISLATURE. COPYRIGHT SECURED. Trenton; N. J. T. F. FITZGERALD, LEGISLATIVE REPORTER, Compiler and Publisher. Entered, according to act of Congress, in the year 1890, by THOMAS F. FITZGERALD, In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. 0~ The newspaper press are welcome to use such parts of the work as they may desire, on giving credit therefor to the Manual. MacCrellish & Quigley, Printers, Opp. Post Office, Trenton, N. J. RIW JERSEY STATE LIBRARY DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION TEINTON. NEW JERSEY EfiirEMDfl'If 1891 1891 JAN. JULY 15 16 22 23 29 30 AUG. FEB. 5 12 19|.v 2627 25 26 ...I... MAR. SEPT. i\ 2 8 9 1516 262; 22 23 29 30 APRIL 2' 3 OCT. 6 7 1314 20 21 27 28 MAY. NOV. 3; 4 1011 1718 24 25 JUNE. DEO. 1| 2 8[ 9 1516 22 23 29 30 PERPETUAL CALENDAR FOR ASCERTAINING THE DAY OF THE WEEK FOR ANY YEAR BETWEEN 1700 AND 2199. Table of Dominical Month. Letters. year of the Jan. Oct. century. Feb. Mar. -

Provenance 2020-08-04

Maryland Province Archives, Detailed Provenance The Archives of the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus (also referred to as the Maryland Province Archives, or MPA), has been on deposit at the Booth Family Center for Special Collections (BFCSC) at Georgetown University since 1977. The Maryland Province made two additional deposits to the BFCSC in 1992 and 2011. In 2018, the University and the Province signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), which renewed the agreement placing the MPA on deposit and allowed the BFCSC to continue preserving these materials and making them available to researchers. The MOU also made provisions for additional, unspecified materials to be sent from the Province to the BFCSC. The Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen retains ownership of the collection. Selection of Georgetown as Repository and Early Finding Aids The selection of Georgetown University as the home of the MPA reflects the institution’s historical role within the Province. In the early nineteenth century, Georgetown College served as the principal residence of the Provincials and Procurators. The Maryland Province also followed the customary practice of the Society of Jesus by depositing the records of their Houses at the “academy” geographically closest to them. Accordingly, Georgetown College was the logical repository for the records of the missions in Maryland and Pennsylvania and the plantations established to support the Province. The MPA also includes papers of the Province that were initially collected by the Georgetown University Archives (GUA). There are some Provincial documents that were probably inadvertently retained by the GUA when the College’s records were separated from the Province’s records in the 1850s. -

The Maryland Jesuits

PART I THE JESUIT MISSION OF MISSOURI CHAPTER I THE MARYLAND JESUITS § I. THE MARYLAND MISSION The history of the Jesuit Mission of Maryland begins with the name of Father Andrew White, who, with his fellow-Jesuits, Father John Altham and Thomas Gervase, a coadjutor-brother, was among the passengers that disembarked from the Ark at St. Clement's Island, Maryland, March 25, 1634. The "Apostle of Maryland," as Father White has come to be known, labored strenuously through fourteen years on behalf of the white and Indian population of the colony, leav ing behind him on his forced return to England an example of mis sionary zeal which his Jesuit successors sought to follow lor a century and more down to the painful period of the Suppression As a conse quence of that event the former Jesuit priests of the Maryland Mission organized themselves into a legal body known as the "Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen" for the purpose of holding by due legal tenure the property belonging to the Society of Jesus in Maryland and of restoring it to the Society in case the latter should be canonically reestablished x During the entire period of the Suppression the Jesuits maintained a canonical existence in Russia When in 1803 Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore and his coadjutor, Bishop Leonard Neale, both former Jesuits themselves, petitioned the Father General, Gabriel Gruber, to affiliate the Maryland ex-Jesuits to the Society as existing in Russia, the latter in a communication from St. Petersburg authorized Bishop Carroll to prepare the way for a Jesuit mission in Maryland by appointing a superior. -

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources Tier 1 Final EIS Volume 1 NEC FUTURE Appendix EE.09 - Cultural Resources: Data Geography Affected Environment Environmental Consequences Context Area NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE State County Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line DC District of Columbia 10 21 0 10 21 0 0 3 0 0 4 0 49 249 0 54 248 0 MD Prince George's County 0 7 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 23 0 1 23 0 MD Anne Arundel County 0 3 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 8 0 0 8 0 MD Howard County 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 1 3 0 MD Baltimore County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 10 0 MD Baltimore City 3 44 0 3 46 0 0 1 0 0 5 0 25 212 0 26 213 0 MD Harford County 0 5 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 12 0 1 15 0 MD Cecil County 0 6 2 0 8 2 0 0 2 0 1 2 0 11 2 0 11 2 DE New Castle County 3 64 2 3 67 2 0 2 1 0 5 2 3 187 1 4 186 2 PA Delaware County 0 4 0 1 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 18 0 1 18 0 PA Philadelphia County 9 85 1 10 87 1 0 2 1 3 4 1 57 368 1 57 370 1 PA Bucks County 3 8 1 3 8 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 3 15 1 3 15 1 NJ Burlington County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 17 0 1 17 0 NJ Mercer County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 0 2 0 0 2 5 40 1 6 40 1 NJ Middlesex County 1 20 2 1 20 2 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 42 2 1 42 2 NJ Somerset County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 4 0 NJ Union County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 1 1 0 2 1 2 17 1 2 17 1 NJ Essex County 1 24 1 1 26 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 65 1 1 65 1 NJ Hudson County -

Open National Register Form

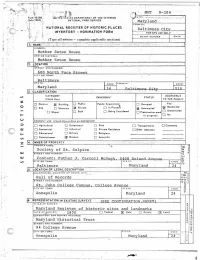

'! . ii .J . ··f o;~ - ~ '! ~· .;.' tr· r -< ~ MHT B-10 4 -. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR .• "-~~ ~ED ':~A~ ES J . NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ..~ ._· COUNT,Y: .,_ .. "'"' NATIONAL REGI STER OF HISTORIC PLACES Baltimor e Citv INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM F FOR NPS USE ONLY \f ENTRY .NUMBER DATE .. (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) : ..· . ..{ .•.·.. .·.·· :·: COMMON: .l .~ -. Mother Seton House ,, AN D I OR HISTORIC: _.... , _ ___Mo __t her Seton Hou se !2. LO C AT IO~N:.._~~~~~~~~~~~-'-"~~~~.-.:..' ~~~"--~~~~~~~~~~ STREET ANO NUMBER: 600 Nort h Pac a StreP+ CITY OR TOWN: Bal timore STATE I CODE !COUNTY : I CODE Maryland I ? .d I ~::. 1 +-.; ..... ~-~ ("';..., .. I c; H I 'C'-'ASSIFICATtON .. =~ 13. '" -· ' . .:• ... : ... CATEGORY ACCESS! BL E V) OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC :z D District ..ca Building D Public Public Acqui s i ti on: 0 Occupied Yes: 0 .. Restricted D Site 0 Structure QI Private O In Process Ga Unoccupied Ga ,. Un_ re s tri cled 0 Object 0 Bo1h 0 Being Consiclerecl 0 Preservation work 0 No ... in progress 0 u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) :::> 0 Agricultural 0 Government 0 Pork 0 Transporfolion 0 Comme nls a:: 0 Comme rcial 0 lndustriol 0 Privole Reside nce 0 ~! her (Specify) ... 0 Eclucational 0 Military 0 Religious Enterroinmenl Museum Scienllfic 0 ~ D - :z !, . OWNER OF PROPERTY 'OWNER'S NAME: ::s:: .. Q) ,.. Society of St. Sulpice -t W STREET AND NUMBER: ~ "' ...... w Contact: Father J. Carroll McHurrh ~40R Rn l ~Mn nuonp~ Q) CITY OR TOWN: S TA TE:: CODE ::i !)., Baltimore Maryland 24 .. ~~5-~ ......_L_O_t ATfON OF~ i'foA"C'6escRiPTiDN couRTHOUSE , RE GISTRY oF D E EDS.