Making Public Service Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Cite This Article

This is an Accepted Manuscript of a chapter published in Me- dia Convergence Handbook Vol. 1. Journalism, Broadcasting, and Social Media Aspects of Convergence To cite this article: Villi, Mikko, Matikainen, Janne and Khaldarova, Irina (2015) Recommend, Tweet, Share: User-Distributed Content (UDC) and the Convergence of News Media and Social Networks. In Media Convergence Handbook Vol. 1. Journalism, Broadcast- ing, and Social Media Aspects of Convergence, edited by Ar- tur Lugmayr and Cinzia Dal Zotto. Heidelberg: Springer, 289- 306. 2 Recommend, Tweet, Share: User- Distributed Content (UDC) and the Convergence of News Media and Social Networks Mikko Villi [email protected] Janne Matikainen [email protected] Irina Khaldarova [email protected] Abstract The paper explores how the participatory audience dis- seminates the online content produced by news media. Here, user- distributed content (UDC) acts as a conceptual framework. The con- cept of UDC refers to the process by which the mass media con- verge with the online social networks through the intentional use of social media features and platforms in order to expand the number of content delivery channels and maximize visibility online. The focus of the paper is both on the news media’s internal use (social plugins) and external use (Facebook pages, Twitter accounts) of social media tools and platforms in content distribution. The study draws on the examination of fifteen news media in seven countries. The data con- sists of almost 50,000 news items and the communicative activity surrounding them. The three main findings of the study are: (1) the audience shares online news content actively by using social plugins, (2) the activity of the news media in social media (especial- ly on Facebook and Twitter) impacts the activity of the audience, and (3) the news media are more active on Twitter than on Face- 3 book, despite the fact that the audience is often more active on Face- book. -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

The Per Gessle Selection - Sommartider Vitt Och Rosé Har Premiär Idag!

2013-04-08 12:09 CEST The Per Gessle Selection - Sommartider vitt och rosé har premiär idag! Per Gessle är van vid succéer och eftersom både kritiker och publik älskade hans italienska viner ”Furet” och ”Kurt och Lisa” är han, liksom vi, mer än nöjd med sin debut i vinbranschen. Nu är det dags för två läckra franska uppföljare i The Per Gessle Selection - boxarna ”Sommartider” - en vit och en rosé. Världspremiär i beställningssortimentet idag, den 8 april! Inget kan vara mer efterlängtat efter en evighetslång vinter än ett löfte om ljusare och varmare tider! Per Gessle står själv för den somriga box-dekoren som leder tankarna till härliga, lata sommardagar. Tillsammans med en av Frankrikes mest kända vinproducenter, François Lurton, har han skapat de två nya vinerna av sydfranska druvor. Det vita ”Sommartider” är en läcker kombination av druvorna gros manseng och sauvignon blanc. Friskt, fruktigt och fräscht som en sommardag med fina toner av citrus, lime och svart vinbärsblad. Härligt alldeles på egen hand och jättegott till fisk, kyckling och sallader. ”Sommartider” rosé är skapad av 100% syrah. Sydfranskt somrigt med doft och smak av hallon, röda vinbär och örter. Svalkande gott och sommarens bästa pick-nickvin som matchar det mesta i matväg! . Per Gessle håller världsklass som artist och han väljer förstås att samarbeta med de bästa i sitt vinprojekt ”The Per Gessle Selection”. Tillsammans med topproducenten Allegrini skapade han två hyllade viner från Toscana, ”Furet” döpt efter Pers hemmakvarter i Halmstad och ”Kurt & Lisa" - en hyllning till Pers föräldrar. Francois Lurton är alltså nästa kvalitetsproducent att medverka i ”The Per Gessle Selection”. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

European Public Service Broadcasting Online

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI, COMMUNICATIONS RESEARCH CENTRE (CRC) European Public Service Broadcasting Online Services and Regulation JockumHildén,M.Soc.Sci. 30November2013 ThisstudyiscommissionedbytheFinnishBroadcastingCompanyǡYle.Theresearch wascarriedoutfromAugusttoNovember2013. Table of Contents PublicServiceBroadcasters.......................................................................................1 ListofAbbreviations.....................................................................................................3 Foreword..........................................................................................................................4 Executivesummary.......................................................................................................5 ͳIntroduction...............................................................................................................11 ʹPre-evaluationofnewservices.............................................................................15 2.1TheCommission’sexantetest...................................................................................16 2.2Legalbasisofthepublicvaluetest...........................................................................18 2.3Institutionalresponsibility.........................................................................................24 2.4Themarketimpactassessment.................................................................................31 2.5Thequestionofnewservices.....................................................................................36 -

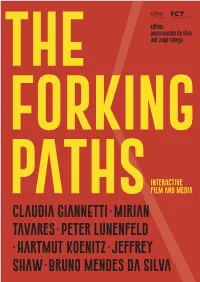

Cadavre Exquis Forking Paths from Surrealism to Interactive Film

THE FORKING PATHS – INTERACTIVE FILM AND MEDIA Editors: Bruno Mendes da Silva Jorge Manuel Neves Carrega CIAC – Centro de Investigação em Artes e Comunicação da Universidade do Algarve FCHS – Universidade do Algarve, Campus de Gambelas, 8005-139 Faro www.ciac.pt | [email protected] ISBN: 978-989-9023-53-6 ISBN (versão eletrónica): 978-989-9023-54-3 Cover: Bloco D Composition, pagination and graphic organization: Juan Manuel Escribano Loza ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FOR THE AUTHORS © 2021 Copyright by Bruno Mendes da Silva and Jorge Manuel Neves Carrega This publication is funded by national funds through the project “UIDP/04019/2020 CIAC” of the Foundation for Science and Technology. Claudia Giannetti is a researcher specialized in contemporary art, aesthetics, media art and the relation between art, science and technology. She is a theoretician, writer and exhibitions curator. For 18 years she war director of institutions and art centres in Spain, Portugal and Germany, including MECAD\ Media Centre of Art & Design (Barcelona) and the Edith- Russ-Haus for Media Art (Oldenburg, Germany). She has curated more than hundred exhibitions and cultural events in international museums. She was Professor in Spanish and Portuguese universities for the past two decades, and visiting professor and lecturer worldwide. She performs the function of adviser in several international multimedia and media art projects. Giannetti has published more than 160 articles and fifteen books in various languages, including: Ars Telemati- ca –Telecomunication, Internet and Cyberspace (Lisbon, 1998; Barcelona, 1998); Aesthetics of the Digital –Syntopy of Art, Science and Technology (Barcelona, 2002; New York/Vienna, 2004; Lisbon, 2011); The Capricious Reason in the 21st Cen- tury: The avatars of the post-industrial information society (Las Palmas, 2006); The Discreet Charm of Technology (Madrid/ Badajoz, 2008); AnArchive(s) – A Minimal Encyclopedia on Archaeology and Variantology of the Arts and Media (Olden- burg, 2014); Image and Media Ecology. -

Kollektivavtal Film TV Video 2017-2020

FILM, TELEVISION AND VIDEO FILMING AGREEMENT 2021–2023 Valid: 2021-01-01 – 2023-05-31 CONTENTS GENERAL PROVISIONS 5 1 Employment 5 2 General obligations 6 3 Cancelled production and breach of contract 7 4 Interruption of service 8 5 Payment of fee and other remuneration 8 6 Travel and subsistence allowances 9 7 Income from employment and annual leave 9 8 Collective agreement occupational pension and insurance 9 9 Working hours 10 10 Special employment provisions 10 SPECIAL PROVISIONS FOR ARTISTS 10 11 Period of employment and fees 10 12 Performance day and performance day remuneration 11 13 Working hours 12 14 Overtime pay 14 15 Work outside the period of employment and special work 15 16 Clothing, wigs and makeup 16 17 General obligations 16 SPECIAL PROVISIONS FOR DIRECTORS 16 18 17 19 17 20 17 21 17 22 18 23 18 24 19 SPECIAL PROVISIONS FOR CHOREOGRAPHERS, SET DESIGNERS AND COSTUME DESIGNERS 19 25 19 26 19 SPECIFIC PROVISIONS FOR THE FOLLOWING PROFESSIONAL CATEGORIES: 19 27 Working hours 20 28 Scheduling working hours 21 29 Unsocial working hours 22 30 Overtime 23 Tnr 690 31 Exceptions to the rules on remuneration for unsocial working hours and overtime under Clauses 29 and 30 23 32 Calculation bases for overtime pay, etc. 24 33 Notice of overtime 24 34 Travel time allowance 24 35 Supplementary duties after the end of the period of employment 25 PAY/FEES/REMUNERATION 26 36 Minimum pay for artists 26 37 Directors 28 § 38 Choreographers, set designers, costume designers and chief photographer (A-photo) 29 39 Minimum pay for technical employees 30 RIGHTS OF USE, ETC. -

BONNIER ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Table of Contents

BONNIER ANNUAL REPORT 2017 Table of Contents Board of Directors’ Report 3 Consolidated Income Statements 12 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 12 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position 13 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 15 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flow 16 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 17 The Parent Company’s Income Statements 42 The Parent Company’s Statements of Comprehensive Income 42 The Parent Company’s Balance Sheets 43 The Parent Company’s Statements of Changes in Equity 44 The Parent Company’s Statements of Cash Flow 44 Notes to the Parent Company’s Financial Statements 45 Auditor’s Report 55 Multi-year Summary 57 Annual Report for the financial year January 1- December 31, 2017 The Board of Directors and the CEO of Bonnier AB, Corporate Registration No. 556508-3663, herewith submit the following annual report and consolidated financial statements on pages 3-54. Translation from the Swedish original BONNIER AB ANNUAL REPORT 2017 2 Board of Directors’ Report The Board of Directors and the CEO of Bonnier AB, corporate reg- Books includes the Group’s book businesses. It includes Bon- istration no. 556508-3663, herewith submit the annual report and nierförlagen, Adlibris, Pocket Shop, Bonnier Media Deutschland, consolidated financial statements for the 2017 financial year. Bonnier Publishing in England, Bonnier Books in Finland, Akateeminen (Academic Bookstore) in Finland, 50% in Cappelen The Group’s business area and Damm in Norway and BookBeat. 2017 was a year of contrasts, Bonnier is a media group with companies in TV, daily newspapers, where above all the German and Swedish publishers continued to business media, magazines, film production, books, e-commerce perform strongly, while physical retail had a challenging year. -

A Critical Policy Analysis on Swedish Regulation of Public Officials

From Public Service to Corporate Positions: A Critical Policy Analysis on Swedish Regulation of Public Officials Transitioning to Non-State Activities Heraclitos Muhire Supervisor: Isabel Schoultz Examiner: Måns Svensson Abstract The topic of government and state officials leaving public service for the private sector has been a recurring talking point in the last decades with multiple countries in the OECD enacting different forms of regulation to contain potential conflicts of interest. In Sweden, legislation specifically regulating the phenomenon was not passed until 2018, when the Act Concerning Restrictions in the Event of Ministers and State Secretaries Transitioning to Non- state Activities (2018:676) (henceforth the Act) was enacted. The Act came with caveats such as the lack of sanctions in case of breach against the regulation as well as only limiting its legal subjects to ministers and state secretaries. This thesis investigates the problem representation that led to the provisions in the Act by conducting Bacchi & Goodwin’s (2016) policy analysis called What’s the Problem Represented to Be (WPR approach) on the legislative history of the Act. By employing Gramsci’s (1971) theoretical concepts of ideology and hegemony and Fisher’s (2009) capitalist realism, the thesis finds that the legislative history sees the issue of transitions between public and private sector as a problem if individuals misuse the otherwise positive exchange of information and knowledge between the public sector and private sector which could erode public trust in state institutions. The findings also indicate that the legislative history does not highlight the role of the private sector, e.g. -

Nordisk Film & Tv Fond, Agreement, 2020–2024

NORDISK FILM & TV FOND, AGREEMENT, 2020–2024 Nordic Council of Ministers (the culture ministers) and the Danish Broadcasting Corporation (DR), TV2 Danmark A/S, Yleisradio OY, MTV OY, the Icelandic National Broadcasting Service (RUV), Síminn, Sýn hf / Stöð 2, the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), TV2 A/S Norway, Discovery Networks Norway, Sveriges Television AB, TV4 AB, Discovery Networks Sweden, C More Entertainment, NENT/Viaplay, the Danish Film Institute, the Finnish Film Foundation, the Icelandic Film Centre, the Norwegian Film Institute and the Swedish Film Institute. OBJECTIVE ARTICLE 1 The purpose of the Nordisk Film & TV Fond, henceforth referred to as the Fund, is to promote the production and distribution of Nordic audiovisual works of high quality, in accordance with rules set out in the Fund’s statutes and administrative guidelines. STATUS AND ACTIVITIES ARTICLE 2 1. The Fund is subject to the legal requirements that apply to funds in the country in which it is based. 2. The Fund must operate in accordance with its statutes, which are enclosed with this agreement, and with the administrative guidelines laid down by the Fund’s Board. ARTICLE 3 1. The above-mentioned parties (hereinafter referred to as the Parties) to this agreement (the Agreement), agree that the Nordic Council of Ministers (the culture ministers), in consultation with the Parties, will lay down statutes for the Fund’s activities. The statutes must at all times be in accordance with the relevant legislation in the country in which the Fund is based. 2. The Nordic Council of Ministers can, in consultation with the Parties, make changes and additions to the statutes. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

Se Bilaga 1 Tillstånd Att Sända Tv Och Sökbar Text-Tv

1/13 Dnr 19/02700 m.fl. BESLUT 2020-02-18 PARTER Se bilaga 1 SAKEN Tillstånd att sända tv och sökbar text-tv __________________ BESLUT Ansökningar om tillstånd som beviljas Myndigheten för press, radio och tv beviljar tillstånd att sända tv och sökbar text-tv för de programtjänster som anges i uppställningen nedan. Förutsättningarna för sändningarna framgår av respektive programtjänsts villkorsbilaga. De anmälda beteckningarna för programtjänster som omfattas av svensk jurisdiktion godkänns. För övriga programtjänster registreras beteckningen. Programtjänstens beteckning Villkors- Dnr Tillståndshavare Inom parentes anges bilaga sändningskvalitet 19/03283 Al Jazeera Media Network Al Jazeera English (sd) tv2020:1 19/03201 Axess Publishing AB Axess (sd) tv2020:2 19/03204 BBC Studios Distribution Ltd BBC Earth (sd) tv2020:3 19/03209 BBC Global News Ltd BBC World News (sd) tv2020:4 19/03237 C More Entertainment AB C More First (sd) tv2020:5 19/03241 C More Entertainment AB C More Fotboll & Stars HD (hd) tv2020:6 19/03242 C More Entertainment AB C More Golf & SF-kanalen (sd) tv2020:7 19/03240 C More Entertainment AB C More Hockey & Hits (sd) tv2020:8 19/03243 C More Entertainment AB C More Live (sd) tv2020:9 19/03238 C More Entertainment AB C More Series (sd) tv2020:10 | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |