Art Carpenter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2000 Popular Woodworking

Popular Woodworking ® www.popularwoodworking.com 42 62 In This Issue Best New 37 Tools of 1999 Before you buy another tool, check out our picks of the 12 best new tools of the year. The Amazing Rise of 42 Home Woodworking You probably think you work 56 54 wood to relax or make furniture for your loved ones. The real reason you’re a woodworker is there are powerful and inexpen- sive machines now on the mar- ket and the fact that people have the money to buy them. 37 By Roger Holmes Table Saw Tenon Jig 52 With many woodworking jigs, simplicity is best. Cabinetmaker Glen Huey shows you how to build the tenoning jig he uses everyday to make tenons and even sliding dovetails. By Glen Huey 58 2 POPULAR WOODWORKING January 2000 America’s BEST Project Magazine! In Every Issue Out On a Limb 6 Welcome Aboard Letters 8 Mail from readers Endurance Test 18 Marples Blue Chip Chisels Flexner on Finishing 22 Why water-based finishes haven't caught on yet Projects From 28 the Past Modular Table and Chairs 52 Tool Test 30 New nailers from Porter-Cable, new Skil drills, Dremel’s new scrollsaw and the Osborne miter guide for your table saw 80 Caption the Cartoon 56 Step Tansu 66 The Incredible Tilting Win a set of Quick Grip clamps Inspired by the traditional cabi- Router Stand Tricks of the Trade netry of Japan, this chest can be Stop busting your knuckles and 84 Custom marking gauges,build your pressed into service in almost any straining your back when you ad- own assembly hammer room of your house. -

Apprenticeship-Type Schemes and Structured Work-Based Learning Programmes Latvia

Apprenticeship-type schemes and structured work-based learning programmes Latvia This article on apprenticeship-type schemes and structured work-based learning programmes is part of a set of articles prepared within Cedefop’s ReferNet network. It complements general information on VET systems available online at http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/Information-services/vet-in-europe-country- reports.aspx. ReferNet is a European network of national partner institutions providing information and analysis on national VET to Cedefop and disseminating information on European VET and Cedefop work to stakeholders in the EU Member States, Norway and Iceland. The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of Cedefop. The article is based on a common template prepared by Cedefop for all ReferNet partners. The preparation of this article has been co-financed by the European Union and AIC. Authors: Zinta Daija, Baiba Ramina, Inga Seikstule © Copyright AIC, 2014 Contents A. Definitions and statistics / basic information ..................................................................... 2 A.1. Apprenticeship in crafts .................................................................................................... 2 A.2. Work-based learning pilot projects .................................................................................... 3 B. Specific features of the above schemes/programmes in Latvia in relation to the following policy challenges identified at the EU level ...................................................................... -

Suggested Courses for Handicraft) an Area of Industrial Arts, for Schools in Thailand

SUGGESTED COURSES FOR HANDICRAFT) AN AREA OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS, FOR SCHOOLS IN THAILAND SUGGESTED COURSES FOR HANDICRAFT~ AN AREA OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS, FOR SCHOOLS IN THAILAND by TongpoonRuamsap II Bachelor of Science Oklahoma State University of Agriculture and Applied Science 1959 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma State University of Agriculture and Applied Science;· in partial fulfillment of the requirements for-the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 1960 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 2 1960 SUGGESTED COURSES FOR HANDICRAFT, AN AREA OF INDUSTRIAL ARTS , FOR SCHOOLS IN THAILAND TONGPOON RUAMSAP Master of Science 1960 THESIS APPROVED: Thesis Advisor, Associate Professor and Head, Department of Industrial Arts Education Dean of the Graduate School 452833 ii ACKNOWLEDG:MENT The author wishes to express his appreciation and grati tude to the following people who helped make this study possible. First to his advisor, Professor Cary L. Hill, Head, School of Industrial Arts Education, Oklahoma State University, for his kind and patient advice and assistance. Second, to Professor Mrs. Myrtle c. Schwarz for her kind assistance and encouragement. Third, to the State Superintendents of Public Instruction of the following states: Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Louisiana, Ohio, Virginia, and Wisconsin. Appreciation is extended t·o Professor John B. Tate and Professor L. H. Bengtson,·who gave kind instructions to the author throughout his study at Oklahoma State University. Tongpoon Ruamsap August, 1959 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I., INTRODUCTION •••••_•&ct•o•••••e•• 1 Part A.. The General Scope of the Study. .. • • 3 The Origin of_th~ Study ........... .. " 3 Needs for the Study ......... -

Traditional Knowledge Systems and the Conservation and Management of Asia’S Heritage Rice Field in Bali, Indonesia by Monicavolpin (CC0)/Pixabay

ICCROM-CHA 3 Conservation Forum Series conservation and management of Asia’s heritage conservation and management of Asia’s Traditional Knowledge Systems and the Systems Knowledge Traditional ICCROM-CHA Conservation Forum Series Forum Conservation ICCROM-CHA Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Rice field in Bali, Indonesia by MonicaVolpin (CC0)/Pixabay. Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Edited by Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court Forum on the applicability and adaptability of Traditional Knowledge Systems in the conservation and management of heritage in Asia 14–16 December 2015, Thailand Forum managers Dr Gamini Wijesuriya, Sites Unit, ICCROM Dr Sujeong Lee, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Forum advisors Dr Stefano De Caro, Former Director-General, ICCROM Prof Rha Sun-hwa, Administrator, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Mr M.R. Rujaya Abhakorn, Centre Director, SEAMEO SPAFA Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts Mr Joseph King, Unit Director, Sites Unit, ICCROM Kim Yeon Soo, Director International Cooperation Division, Cultural Heritage Administration (CHA), Republic of Korea Traditional Knowledge Systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage Edited by Gamini Wijesuriya and Sarah Court ISBN 978-92-9077-286-6 © 2020 ICCROM International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property Via di San Michele, 13 00153 Rome, Italy www.iccrom.org This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution Share Alike 3.0 IGO (CCBY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo). -

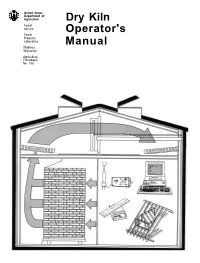

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

Investigation of Selected Wood Properties and the Suitability for Industrial Utilization of Acacia Seyal Var

Fakultät Umweltwissenschaften - Faculty of Environmental Sciences Investigation of selected wood properties and the suitability for industrial utilization of Acacia seyal var. seyal Del and Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile grown in different climatic zones of Sudan Dissertation to achieve the academic title Doctor rerum silvaticarum (Dr. rer. silv.) Submitted by MSc. Hanadi Mohamed Shawgi Gamal born 23.09.1979 in Khartoum/Sudan Referees: Prof. Dr. Dr. habil. Claus-Thomas Bues, Dresden University of Technology Prof Dr. Andreas Roloff, Dresden University of Technology Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. František Hapla, University of Göttingen Dresden, 07.02.2014 1 Acknowledgement Acknowledgement First of all, I wish to praise and thank the god for giving me the strength and facilitating things throughout my study. I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Prof. Dr. Dr. habil. Claus-Thomas Bues , Chair of Forest Utilization, Institute of Forest Utilization and Forest Technology, Dresden University of Technology, for his continuous supervision, guidance, patience, suggestion, expertise and research facilities during my research periods in Dresden. He was my Father and Supervisor, I got many advices from his side in the scientific aspect as well as the social aspects. He taught me how to be a good researcher and gives me the keys of the wood science. I am grateful to Dr. rer. silv. Björn Günther for his help and useful comments throughout the study. He guides me in almost all steps in my study. Dr.-Ing. Michael Rosenthal was also a good guide provided many advices, thanks for him. I would also like to express my thanks to Frau Antje Jesiorski, Frau Liane Stirl, Dipl.- Forsting. -

Strike up the Bandsaw

“America’s leading woodworking authority”™ Strike Up the Bandsaw • Step by Step construction instruction. • A complete bill of materials. • Exploded view and elevation drawings. • How-to photos with instructive captions. • Tips to help you complete the project and become a better woodworker. To download these plans, you will need Adobe Reader installed on your computer. If you want to get a free copy, you can get it at: Adobe Reader. Having trouble downloading the plans? • If you're using Microsoft Internet Explorer, right click on the download link and select "Save Target As" to download to your local drive. • If you're using Netscape, right click on the download link and select "Save Link As" to download to your local drive. WOODWORKER'S JOURNAL ©2007 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published in Woodworker’s Journal “The Complete Woodworker: Time-Tested Projects and Professional Techniques for Your Shop and Home” WJ128 A bandsaw is a tremendously versatile and useful tool—but only if it’s running well. Properly set up, it allows you to create poetry out of wood. Out of adjustment it can cause Blade vocabulary usage that would impress the Thrust guard most seasoned boatswain’s mate. bearing adjustment Tuning up your bandsaw is not a huge undertaking. A couple of quick steps to better align and control your blade will have you cutting smoothly in just a few minutes. Most modern bandsaws have a system of Thrust bearing thrust bearings (those little metal wheels that Guide block the blade’s back edge bumps into) and guide Guide block set screws adjustment blocks that hold the blade in proper alignment. -

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume Adkins, Jim DAW1019 Native American Baskets Part 1 2014 20 DAW1021 Native American Baskets Part 2 2014 21 Arledge, Jimmie DAW0490 Surface Embellishment 2004 10 Avisera, Eli DAW0789 Bowl with Leaves Inlay 2010 1 DAW0791 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring 2010 2 DAW0793 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring in Off-Center 2010 3 DAW0795 Goblet w/Star Segment & Trembleur 2010 4 DAW0797 Square Bowl w/ Off-Center 2010 5 Baldwin, Doug DAW2358 Photography for Wood Turners 2015 1 DAW2360 Photoshop for Wood Turners 2015 2 DAW2660 Light & Shadow - Photographing Wood Objects 2017 1 Barnes, Gary DAW2420 Three-Piece Stacking Salt/Spice Box 2016 1 Bassett, Kevin DAW0665 Turning a Double Natural Edge Bowl 2008 1 DAW2422 An Acorn Ring Box w/ Secret Compartment 2016 2 Batty, Stuart DAW0733 Bowl Turning Techniques using a Gouge 2009 3 DAW0735 The Six Fundamental Wooduring Cuts 2009 4 DAW0755 Dueling Lathes: two different ways to turn a bowl 2009 14 DAW2424 Stuart Batty & Mike Mahoney Dual 2016 3 DAW2426 Bowl Turning w/ the 40/40 Grind 2016 4 DAW2428 Perfecting the Art of Cutting 2016 5 DAW2430 Seven Set-up Fundamentals 2016 6 DAW2692 Stuart Batty and Mike Mahoney Dual 2017 17 Beaver, John DAW2432 Bangles 2016 7 DAW2434 Flying Rib Vase 2016 8 1 SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume DAW2436 Wave Bowls 2016 9 Berry, Bill DAW0737 Turning Tree Crotches 2009 5 DAW2352 Air Brushing on Turnings 2014 26 Bosch, Trent DAW0462 Carving 2003 1 DAW0464 Basic Bowl -

Law As Craft

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 54 Issue 6 Issue 6 - November 2001 Article 2 11-2001 Law as Craft Brett G. Scharffs Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Brett G. Scharffs, Law as Craft, 54 Vanderbilt Law Review 2243 (2001) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol54/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Law as Craft Brett G. Scharffs 54 Vand. L. Rev. 2245 (2001) This Article explores the similarities between the law and other craft traditions, such as carpentry, pottery, and quilting. Its thesis is that law--and in particular adjudica- tion--combine elements of what Aristotle described as practical wisdom, or phronesis, and craft, or techne. Craft knowledge is learned practically through experi- ence and demonstrated through practice, and is contrasted with other concepts, including art, science, mass production, craftiness, and hobby. Crafts are characterized by four simul- taneous identities. First, crafts are made by hand-one at a time-and require not only talent and skill, but also experience and what Karl Llewellyn called "situation sense." Second, crafts are medium specific and are always identified with a material and the technologies invented to manipulate that ma- terial. Third, crafts are characterized by the use and useful- ness of craft objects. -

Sandpaper Presentati#2250F0

SAN JOAQUIN FINE WOODWORKERS ASSOCIATION Meeting Presentation Outline December 18, 2004 Sandpaper and Sanding Techniques • Introduction (Roger) o Introduction of Presenters o Overview of Presentation • Making Sense of Sandpaper (Roger) o Industrial term is “Coated Abrasives” o Definition of “Coated Abrasive” o History of Sandpaper o Present major points of Strother Purdy article . Mr. Purdy was an editor for Fine Woodworking for 4 years . Article was published in issue #125, pages 62-67 o Purdy quote “Sanding is necessary drudge work, improved only by spending less time doing it” o Key to choosing the right sandpaper is knowing how it works o Sandpaper works like a cutting tool . Under magnification, abrasive grains look like small irregularly shaped sawteeth . The grains are supported by a cloth or paper backing and two adhesive bonds • The make coat bonds them to the backing • The size coat locks them into position o As sandpaper is pushed across wood the abrasive grains dig into the surface & cut out minute shavings, called swarf in industry jargon . To the naked eye, these shavings look like dust, but magnified they look like the shavings produced by saws or other cutting tools . The spaces between the abrasive grains serve an important role - they work the way gullets on sawblades do, giving the shavings a place to go . That's why sandpaper designed for wood has what's called an open coat, where only 40% to 70% of the backing is covered with abrasive . Closed-coat sandpaper, where the backing is entirely covered with abrasive, is not appropriate for sanding wood because the swarf has no place to go and quickly clogs the paper o Stearated Sandpaper . -

Dry Kiln Schedules for Commercial Woods-Temperateand Tropical

United States Department of AgricuIture Dry Kiln Schedules Forest Service Forest for Commercial Woods Products Laboratory Temperate and Tropical General Technical Report FPL-GTR-57 R. Sidney Boone Charles J. Kozlik Paul J. Bois Eugene M. Wengert Abstract Acknowledgments This report contains suggested dry kiln schedules for The authors wish to thank Mr. Hiroshi Sumi, Wood over 500 commercial woods, both temperate and TechnoIogy Division , Forestry and Forest Prod u c t s tropical. Kiln schedules are completely assembled Research Institute, Ibaraki, Japan, for supplying and written out for easy use. Schedules for several schedules for Japanese as well as several tropical thicknesses and specialty products (e.g. squares, woods. Significant assistance in computer handle stock, gunstock blanks) are given for many programming and table formatting was provided by species. The majority of the schedules are from the David B. McKeever, Research Forester, and world literature, with emphasis on U.S., Canadian, and W. W. Wlodarczyk, Computer Programmer Analyst, British publications. Revised schedules have been both of the Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, suggested for western U.S. and Canadian softwoods U.S. Department of Agriculture, Madison, WI. and for the U.S. southern pines. Current thinking on high-temperature drying (temperatures exceeding 212 °F) schedules for both softwoods and hardwoods is reflected in suggested high-temperature schedules for selected species. Keywords: Lumber drying, hardwoods, softwoods, kiln drying, conventional-temperature ( < 180 °F) schedules, elevated-temperature (180-212 °F) schedules, high-temperature ( > 212 °F) schedules, tropical woods, temperate woods. August 1988 Boone, R. Sidney; Kozlik, Charles J.; Bois, Paul J.; Wengert, Eugene M. -

2018: Going by So Quickly. As a Club We’Ve Had a Really Perhaps We Can Find Someone Good Year

VALLEY WOODWORKERS OF WEST VIRGINIA JUNE 2018 Volume 28 Issue 6 The June 2018 Next Meeting May 10, 2018 6:30pm VWWV Headquarters NOVICE TO PROFESSIONAL, JOINING TOGETHER FOR THE JOY OF WOODWORKING. IN THIS ISSUE 2018: Going by so quickly. As a club we’ve had a really perhaps we can find someone good year. So far, our to come teach it to the club. members have learned We are only 27 weeks until about table saw safety, Christmas, so that means we Show & Tell common woodworking need to put our Santa’s helper We love seeing what our members have joints, router planning, and been making! hats on and start making toys steam beading of wood. for our area’s girls and boys. If Page 2 Dozens of projects have everyone contributes a little been shared with the club bit, a lot can get done! including bandsaw boxes of all shapes and sizes, blankest chests, side tables, wooden toys, candlestick holders, platters and bowls. Let’s make the rest of the year even better! Share a skill you have with the club by Shop update giving a presentation to the The club’s workshop update from our Shop membership, or suggest a skill director. you would like to learn, and Page 6 VALLEY WOODWORKERS OF WEST VIRGINIA JUNE 2018 | Issue 6 2 Show & Tell Andy Sheetz: Wooden toys- He shared wooden airplanes, toy cars loving called “minis” and a tool set comprised of a square, a handsaw, a mallet, a chisel and a tool tray. All the toys are finished with salad bowl finish in case someone should decide to take a bite out of them.