BANDSAW BOXES Quick and Easy to Build -- with a “One-Of-A-Kind” Flair That Makes Them Sell Fast, Too

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art Carpenter

Art Carpenter's first chair, an experiment using rawhide and lathe-turned parts, satisfies his criteria for good furniture: 'First, it looks like a chair—it doesn't look like an eagle or a tree—you know right away where to put your butt. Second, it lasts, it's rugged, it will stand the use for which it was meant for many years without repair. This has been a desk chair in my shop for 22 years, and its joints are as tight today as they were when they were made. Third, there is a directness and clarity of construc- tion, which gives pleasure to the hand and to the eye. And fourth, it is relatively fast to produce, given the primitive methods of my shop.' under his mother's maiden name, Espenet) is more than a role model—he has nurtured the growth of a generation of inde- pendent designer-craftsmen. Ask the successful woodworkers in the San Francisco Bay Area how they began and you'll hear, "I taught myself, except for some time I spent with Art." Even those who don't spend more than an afternoon at Carpenter's shop leave with practical direction to make it on their own—which is really the spirit of the Guild. The Bau- lines Guild works because it is the simple extension of the self-styled craftsmen who characterize the Bay Area. It prob- ably would not have worked so well were it not for the special place Bolinas is, but it's hard to imagine the Guild at all without Art Carpenter. -

Dry Kiln Operator's Manual

United States Department of Agriculture Dry Kiln Forest Service Operator's Forest Products Laboratory Manual Madison, Wisconsin Agriculture Handbook No. 188 Dry Kiln Operator’s Manual Edited by William T. Simpson, Research Forest Products Technologist United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory 1 Madison, Wisconsin Revised August 1991 Agriculture Handbook 188 1The Forest Products Laboratory is maintained in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. This publication reports research involving pesticides. It does not contain recommendations for their use, nor does it imply that the uses discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesticides must be registered by appropriate State and/or Federal agencies before they can be recommended. CAUTION, Pesticides can be injurious to humans, domestic animals, desirable plants, and fish or other wildlife-if they are not handled or applied properly. Use all pesticides selectively and carefully. Follow recommended practices for the disposal of surplus pesticides aand pesticide containers. Preface Acknowledgments The purpose of this manual is to describe both the ba- Many people helped in the revision. We visited many sic and practical aspects of kiln drying lumber. The mills to make sure we understood current and develop- manual is intended for several types of audiences. ing kiln-drying technology as practiced in industry, and First and foremost, it is a practical guide for the kiln we thank all the people who allowed us to visit. Pro- operator-a reference manual to turn to when questions fessor John L. Hill of the University of New Hampshire arise. It is also intended for mill managers, so that they provided the background for the section of chapter 6 can see the importance and complexity of lumber dry- on the statistical basis for kiln samples. -

Investigation of Selected Wood Properties and the Suitability for Industrial Utilization of Acacia Seyal Var

Fakultät Umweltwissenschaften - Faculty of Environmental Sciences Investigation of selected wood properties and the suitability for industrial utilization of Acacia seyal var. seyal Del and Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Delile grown in different climatic zones of Sudan Dissertation to achieve the academic title Doctor rerum silvaticarum (Dr. rer. silv.) Submitted by MSc. Hanadi Mohamed Shawgi Gamal born 23.09.1979 in Khartoum/Sudan Referees: Prof. Dr. Dr. habil. Claus-Thomas Bues, Dresden University of Technology Prof Dr. Andreas Roloff, Dresden University of Technology Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. František Hapla, University of Göttingen Dresden, 07.02.2014 1 Acknowledgement Acknowledgement First of all, I wish to praise and thank the god for giving me the strength and facilitating things throughout my study. I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Prof. Dr. Dr. habil. Claus-Thomas Bues , Chair of Forest Utilization, Institute of Forest Utilization and Forest Technology, Dresden University of Technology, for his continuous supervision, guidance, patience, suggestion, expertise and research facilities during my research periods in Dresden. He was my Father and Supervisor, I got many advices from his side in the scientific aspect as well as the social aspects. He taught me how to be a good researcher and gives me the keys of the wood science. I am grateful to Dr. rer. silv. Björn Günther for his help and useful comments throughout the study. He guides me in almost all steps in my study. Dr.-Ing. Michael Rosenthal was also a good guide provided many advices, thanks for him. I would also like to express my thanks to Frau Antje Jesiorski, Frau Liane Stirl, Dipl.- Forsting. -

Strike up the Bandsaw

“America’s leading woodworking authority”™ Strike Up the Bandsaw • Step by Step construction instruction. • A complete bill of materials. • Exploded view and elevation drawings. • How-to photos with instructive captions. • Tips to help you complete the project and become a better woodworker. To download these plans, you will need Adobe Reader installed on your computer. If you want to get a free copy, you can get it at: Adobe Reader. Having trouble downloading the plans? • If you're using Microsoft Internet Explorer, right click on the download link and select "Save Target As" to download to your local drive. • If you're using Netscape, right click on the download link and select "Save Link As" to download to your local drive. WOODWORKER'S JOURNAL ©2007 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published in Woodworker’s Journal “The Complete Woodworker: Time-Tested Projects and Professional Techniques for Your Shop and Home” WJ128 A bandsaw is a tremendously versatile and useful tool—but only if it’s running well. Properly set up, it allows you to create poetry out of wood. Out of adjustment it can cause Blade vocabulary usage that would impress the Thrust guard most seasoned boatswain’s mate. bearing adjustment Tuning up your bandsaw is not a huge undertaking. A couple of quick steps to better align and control your blade will have you cutting smoothly in just a few minutes. Most modern bandsaws have a system of Thrust bearing thrust bearings (those little metal wheels that Guide block the blade’s back edge bumps into) and guide Guide block set screws adjustment blocks that hold the blade in proper alignment. -

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019

SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume Adkins, Jim DAW1019 Native American Baskets Part 1 2014 20 DAW1021 Native American Baskets Part 2 2014 21 Arledge, Jimmie DAW0490 Surface Embellishment 2004 10 Avisera, Eli DAW0789 Bowl with Leaves Inlay 2010 1 DAW0791 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring 2010 2 DAW0793 Boxes with New Ideas: Texturing and Coloring in Off-Center 2010 3 DAW0795 Goblet w/Star Segment & Trembleur 2010 4 DAW0797 Square Bowl w/ Off-Center 2010 5 Baldwin, Doug DAW2358 Photography for Wood Turners 2015 1 DAW2360 Photoshop for Wood Turners 2015 2 DAW2660 Light & Shadow - Photographing Wood Objects 2017 1 Barnes, Gary DAW2420 Three-Piece Stacking Salt/Spice Box 2016 1 Bassett, Kevin DAW0665 Turning a Double Natural Edge Bowl 2008 1 DAW2422 An Acorn Ring Box w/ Secret Compartment 2016 2 Batty, Stuart DAW0733 Bowl Turning Techniques using a Gouge 2009 3 DAW0735 The Six Fundamental Wooduring Cuts 2009 4 DAW0755 Dueling Lathes: two different ways to turn a bowl 2009 14 DAW2424 Stuart Batty & Mike Mahoney Dual 2016 3 DAW2426 Bowl Turning w/ the 40/40 Grind 2016 4 DAW2428 Perfecting the Art of Cutting 2016 5 DAW2430 Seven Set-up Fundamentals 2016 6 DAW2692 Stuart Batty and Mike Mahoney Dual 2017 17 Beaver, John DAW2432 Bangles 2016 7 DAW2434 Flying Rib Vase 2016 8 1 SWAT Videos by Demonstrator 1/12/2019 media id title year volume DAW2436 Wave Bowls 2016 9 Berry, Bill DAW0737 Turning Tree Crotches 2009 5 DAW2352 Air Brushing on Turnings 2014 26 Bosch, Trent DAW0462 Carving 2003 1 DAW0464 Basic Bowl -

Sandpaper Presentati#2250F0

SAN JOAQUIN FINE WOODWORKERS ASSOCIATION Meeting Presentation Outline December 18, 2004 Sandpaper and Sanding Techniques • Introduction (Roger) o Introduction of Presenters o Overview of Presentation • Making Sense of Sandpaper (Roger) o Industrial term is “Coated Abrasives” o Definition of “Coated Abrasive” o History of Sandpaper o Present major points of Strother Purdy article . Mr. Purdy was an editor for Fine Woodworking for 4 years . Article was published in issue #125, pages 62-67 o Purdy quote “Sanding is necessary drudge work, improved only by spending less time doing it” o Key to choosing the right sandpaper is knowing how it works o Sandpaper works like a cutting tool . Under magnification, abrasive grains look like small irregularly shaped sawteeth . The grains are supported by a cloth or paper backing and two adhesive bonds • The make coat bonds them to the backing • The size coat locks them into position o As sandpaper is pushed across wood the abrasive grains dig into the surface & cut out minute shavings, called swarf in industry jargon . To the naked eye, these shavings look like dust, but magnified they look like the shavings produced by saws or other cutting tools . The spaces between the abrasive grains serve an important role - they work the way gullets on sawblades do, giving the shavings a place to go . That's why sandpaper designed for wood has what's called an open coat, where only 40% to 70% of the backing is covered with abrasive . Closed-coat sandpaper, where the backing is entirely covered with abrasive, is not appropriate for sanding wood because the swarf has no place to go and quickly clogs the paper o Stearated Sandpaper . -

Dry Kiln Schedules for Commercial Woods-Temperateand Tropical

United States Department of AgricuIture Dry Kiln Schedules Forest Service Forest for Commercial Woods Products Laboratory Temperate and Tropical General Technical Report FPL-GTR-57 R. Sidney Boone Charles J. Kozlik Paul J. Bois Eugene M. Wengert Abstract Acknowledgments This report contains suggested dry kiln schedules for The authors wish to thank Mr. Hiroshi Sumi, Wood over 500 commercial woods, both temperate and TechnoIogy Division , Forestry and Forest Prod u c t s tropical. Kiln schedules are completely assembled Research Institute, Ibaraki, Japan, for supplying and written out for easy use. Schedules for several schedules for Japanese as well as several tropical thicknesses and specialty products (e.g. squares, woods. Significant assistance in computer handle stock, gunstock blanks) are given for many programming and table formatting was provided by species. The majority of the schedules are from the David B. McKeever, Research Forester, and world literature, with emphasis on U.S., Canadian, and W. W. Wlodarczyk, Computer Programmer Analyst, British publications. Revised schedules have been both of the Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, suggested for western U.S. and Canadian softwoods U.S. Department of Agriculture, Madison, WI. and for the U.S. southern pines. Current thinking on high-temperature drying (temperatures exceeding 212 °F) schedules for both softwoods and hardwoods is reflected in suggested high-temperature schedules for selected species. Keywords: Lumber drying, hardwoods, softwoods, kiln drying, conventional-temperature ( < 180 °F) schedules, elevated-temperature (180-212 °F) schedules, high-temperature ( > 212 °F) schedules, tropical woods, temperate woods. August 1988 Boone, R. Sidney; Kozlik, Charles J.; Bois, Paul J.; Wengert, Eugene M. -

2018: Going by So Quickly. As a Club We’Ve Had a Really Perhaps We Can Find Someone Good Year

VALLEY WOODWORKERS OF WEST VIRGINIA JUNE 2018 Volume 28 Issue 6 The June 2018 Next Meeting May 10, 2018 6:30pm VWWV Headquarters NOVICE TO PROFESSIONAL, JOINING TOGETHER FOR THE JOY OF WOODWORKING. IN THIS ISSUE 2018: Going by so quickly. As a club we’ve had a really perhaps we can find someone good year. So far, our to come teach it to the club. members have learned We are only 27 weeks until about table saw safety, Christmas, so that means we Show & Tell common woodworking need to put our Santa’s helper We love seeing what our members have joints, router planning, and been making! hats on and start making toys steam beading of wood. for our area’s girls and boys. If Page 2 Dozens of projects have everyone contributes a little been shared with the club bit, a lot can get done! including bandsaw boxes of all shapes and sizes, blankest chests, side tables, wooden toys, candlestick holders, platters and bowls. Let’s make the rest of the year even better! Share a skill you have with the club by Shop update giving a presentation to the The club’s workshop update from our Shop membership, or suggest a skill director. you would like to learn, and Page 6 VALLEY WOODWORKERS OF WEST VIRGINIA JUNE 2018 | Issue 6 2 Show & Tell Andy Sheetz: Wooden toys- He shared wooden airplanes, toy cars loving called “minis” and a tool set comprised of a square, a handsaw, a mallet, a chisel and a tool tray. All the toys are finished with salad bowl finish in case someone should decide to take a bite out of them. -

Multi Drawer Bandsaw Box

instructables Multi Drawer Bandsaw Box by Highlandboxes. What i used 1 douglas fir board 1 inch thick and 6 inches wide 1 douglas fir board 1/2 inch thick 6 inch wide Thickness planer Sanding grits - 120, 180, 240, 360, 400, 600 sanding sealer suede tex and glue wood glue Spray Lacquer https://youtu.be/5kL3PxkVZHc Multi Drawer Bandsaw Box: Page 1 Step 1: For this project i used 2 Douglas fir boards one 1 inch thick and 1 1/2 inch thick both 6 inches wide. I cut the 1 inch board into 5 x 12 inch sections these will be the top bottom and 3 drawer sections. I also 2 x 12 of the 1/2 inch boards these will go between the draw sections. I put all the boards though the thickness planer before putting them in the order i wanted them to be placed in box. Step 2: Next i take 3 1 inch drawer boards and draw out the plan for the drawers using a compass for the curved drawers. The designing of the drawers takes a while if you want to use the space well, but you are free to design any style of draw you wish. I had some square and some oval the oval ones can be pushed or pulled out of the box. Multi Drawer Bandsaw Box: Page 2 Step 3: I then cut all the drawers out leaving the frame for these. I then glued frame for the drawers in place. After the glue had dried i sanded and used sand sealer before gluing the box together leaving the drawers out . -

The Makers Meeting 2019

Newsletter of the Sonoma County Woodworkers Association Volume 39, Issue 11 December 2019 The Makers Meeting 2019 The long wait for rain has finally ended, and with The next date on our calendar is our official Annual it the attendant anxiety over danger of wildfire. Meeting, to be held on December 10 at 7pm, also in Whew! the Sonoma County Museum. This meeting The Evening with the Judges saw a large entails elections and decisions about turn out of the membership, as everyone association business for the coming listened attentively to what the three year. It is also the Makers Meeting, judges had to say. Had the Show which may well be the most Chair, on behalf of the Museum anticipated meeting of the year, staff, not placed a time limit on the when the makers of the Artistry meeting, we might still be there. It in Wood entries discuss their was a fun and educational evening. pieces and field questions from In addition to the traditional Best the audience. Whether you are a of category awards, the judges maker or someone who simply bestowed Awards of Excellence appreciates good craft, don’t on sixteen spectacular examples of miss this one. It promises to be a woodwork. In fact, all 74 pieces in fun evening. the Show are exemplary works. The Show opened to the public on Friday, November 22, and was the largest opening night audience in this editor’s memory. Award of Excellence: A Mouse’s Life by Paul Marini Kudos to Don Jereb and his team for a first-rate job. -

February 2019

VALLEY WOODWORKERS OF WEST VIRGINIA Volume 29 Issue 2 February 2019 Next Meeting February 21,2019, 6:30 pm VWWV Headquarters N Novice to professional joining together for the joy of woodworking. IN THIS ISSUE are lined up and topics for other presentations are under Hello Members! Club Project Beginnings If you trust groundhogs, spring is consideration. What (or who) would purportedly just around the corner. you like to see? New Member Initiative That means days that are longer, On a final note, consider how Club Reminders & Tidbits warmer, and of course, the arrival of warmer weather is going to affect spring cleaning. I’d like to encourage your woodworking. Do you have an club members to consider bringing unheated shop that will see more those tools they don’t really need (or use as the temperature gets more wish to upgrade) to the March bearable? Or will outdoor activities meeting for auction. This benefits pull you away from woodworking your club and of course, provides until weather cools back down? that needed space for the items you What are your short-term priorities win at the auction. Don’t deny it… for spring? there’ll be things up for auction that you just can’t live without. I look forward to seeing everyone at the club! January Show & Tell Speaking of your club, I encourage everyone to participate in the shop Sincerely- Table Saw Alignment activities. Shop hours are running Events of Interest smoothly and it’s very satisfying to Jason Brown,2019 VWWV President Club Contact Information see the progress members are making on their projects. -

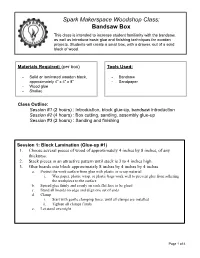

Spark Makerspace Woodshop Class: Bandsaw

Spark Makerspace Woodshop Class: Bandsaw Box This class is intended to increase student familiarity with the bandsaw, as well as introduce basic glue and finishing techniques for wooden projects. Students will create a small box, with a drawer, out of a solid block of wood. Materials Required: (per box) Tools Used: - Solid or laminated wooden block, - Bandsaw approximately 4” x 4” x 8” - Sandpaper - Wood glue - Shellac Class Outline: Session #1 (2 hours) : Introduction, block glue-up, bandsaw introduction Session #2 (4 hours) : Box cutting, sanding, assembly glue-up Session #3 (2 hours) : Sanding and finishing Session 1: Block Lamination (Glue-up #1) 1. Choose several pieces of wood of approximately 4 inches by 8 inches, of any thickness. 2. Stack pieces in an attractive pattern until stack is 3 to 4 inches high. 3. Glue boards into block approximately 8 inches by 4 inches by 4 inches a. Protect the work surface from glue with plastic or scrap material i. Wax paper, plastic wrap, or plastic bags work well to prevent glue from adhering the workpiece to the surface b. Spread glue thinly and evenly on each flat face to be glued c. Stand all boards on edge and align one set of ends d. Clamp i. Start with gentle clamping force, until all clamps are installed ii. Tighten all clamps firmly e. Let stand overnight Page 1 of 4 Session 2: Cutting, Sand, and Glue-up #2 1. Choose which side of the block is going to be the front face, and which will be the bottom. a.