The West of Dale L. Morgan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fawn Brodie and Her Quest for Independence

Fawn Brodie and Her Quest for Independence Newell G. Bringhurst FAWN MCKAY BRODIE IS KNOWN IN MORMON CIRCLES primarily for her con- troversial 1945 biography of Joseph Smith — No Man Knows My History. Because of this work she was excommunicated from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In the 23 May 1946 summons, William H. Reeder, presi- dent of the New England Mission, charged her with apostasy: You assert matters as truths which deny the divine origin of the Book of Mormon, the restoration of the Priesthood and of Christ's Church through the instrumentality of the Prophet Joseph Smith, contrary to the beliefs, doctrines, and teachings of the Church. This reaction did not surprise the author of the biography. For Brodie had approached the Mormon prophet from a "naturalistic perspective" — that is, she saw him as having primarily non-religious motives. As she later noted: "I was convinced before I ever began writing that Joseph Smith was not a true Prophet" (1975, 10). Writing No Man Knows My History was Brodie's declaration of independence from Mormonism. In the words of Richard S. Van Wagoner, Brodie's "compulsion to rid herself of the hooks that Mor- monism had embedded in her soul centered on her defrocking Joseph Smith" (1982, 32). She herself, in a 4 November 1959 letter to her uncle, Dean Brim- hall, described the writing of the biography as "a desperate effort to come to terms with my childhood." NEWELL G. BRINGHURST is an instructor of history and political science at College of the Sequoias in Visalia, California. -

BRODIE: the a Personal Look at Mormonisrn’S Best-Known Rebel

BRODIE: the A personal look at Mormonisrn’s best-known rebel RICHARD S. VAN WAGONER LMOST as much as we love to love our folk unseen influences which shape our destinies, I took my heroes, we Mormons love to hate our heretics. stand with the ’heretics’; and, as it happened, my own AWe lick our chops at the thought of John C. was the first woman’s name enrolled in their cause. Bennett spending his autumn years raising chickens in The most recent name enrolled on the list of women Polk City, Iowa--so far a fall for the once-proud heretics is Sonia Johnson. Trading barbs with Utah’s Brigadier General in the Invincible Light Dragoons of Mormon Senator Orrin Hatch, Johnson quickly rose to Illinois and member of Joseph Smith’s First Presidency. prominence as a fervent spokeswoman for "Mormons We remember with delight millionaire Sam Brannan of for ERA." Her outspoken opposition to Church political California gold rush fame, once high and mighty enough activism over the Equal Rights Amendment resulted in to refuse to give up Church tithes until Brigham Young national press attention, loss of her Church sent a "receipt signed by the Lord," dying of a bowel membership, and delicious hissings from Church infection, wifeless and penniless. We retell with relish members in general. the sad tale of stroke-ravaged Thomas B. Marsh, the man who might have been Church president upon The best-known Mormon rebel of all time, however, Joseph Smith’s death, returning to the Church in 1856 "a neither led a protest movement against polygamy nor poor decrepid [sic], broken down old man . -

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 8 Number 1 Article 14 1996 “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Gary F. Novak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Novak, Gary F. (1996) "“The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol8/iss1/14 This Historical and Cultural Studies is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Gary F. Novak Reference FARMS Review of Books 8/1 (1996): 122–67. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Review of Dale Morgan On Early Mormonism: Correspondence and a New History (1986), edited by John Phillip Walker. John Phillip Walker, ed. Dale Morgan On Early Mor· mOllism: Correspondence and a New History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1986. viii + 414 pp., with bibliography, no index. $20.95 (out of print). Reviewed by Gary F. Novak "The Most Convenient Form of Error": Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon We are onl y critica l about the th ings we don't want to believe. -

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Book Reviews 149 Book Reviews WILL BAGLEY. Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002. xxiv + 493 pp. Illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index. $39.95 hardback.) Reviewed by W. Paul Reeve, assistant professor of history, Southern Virginia University, and Ardis E. Parshall, independent researcher, Orem, Utah. Explaining the violent slaughter of 120 men, women, and children at the hands of God-fearing Christian men—priesthood holders, no less, of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is no easy task. Biases per- meate the sources and fill the historical record with contradictions and polemics. Untangling the twisted web of self-serving testimony, journals, memoirs, government reports, and the like requires skill, forthrightness, integrity, and the utmost devotion to established standards of historical scholarship. Will Bagley, a journalist and independent historian with sever- al books on Latter-day Saint history to his credit, has recently tried his hand at unraveling the tale. Even though Bagley claims to be aware of “the basic rules of the craft of history” (xvi), he consistently violates them in Blood of the Prophets. As a result, Juanita Brooks’ The Mountain Meadows Massacre remains the most definitive and balanced account to date. Certainly there is no justification for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Mormon men along with Paiute allies acted beyond the bounds of reason to murder the Fancher party, a group of California-bound emigrants from Arkansas passing through Utah in 1857. It is a horrific crime, one that Bagley correctly identifies as “the most violent incident in the history of America’s overland trails” (xiii), and it belongs to Utah and the Mormons. -

Jedediah Strong Smith's Lands Purchased by Ralph Smith in Ohio

Newsletter of the Jedediah Smith Society • University of the Pacific, Stockton, California FALL/WINTER 2010 - SPRING 2011 Jedediah Strong Smith’s located in Richland County, Green Township. (Note: Dale Morgan’s book seems to be mistaken when it says that they moved Lands to Ashland County Ohio in 1817. Ashland County did not exist until 1846, having been made up of parts of Wayne and Richland Purchased by Ralph Smith in Ohio Counties.) It is assumed that young Jedediah Strong Smith lived By Roger Williams with his parents and siblings at this location until approximately 1820, when he left home, headed west and ended up in St. Louis, Missouri in the early spring of 1821. It was also inferred that the I have read the book “Jedediah Smith Smith family was not monetarily well off, so that may have been a and the Opening of the West” by Dale factor in Jedediah S. Smith’s decision to leave home. (2) Morgan, copyright 1953; wherein he has provided several letters of Jedediah I have searched the tax records as far back as 1826 and have S. Smith to his mother and father and not found where Jedediah Smith Sr. or Ralph Smith owned land his brother Ralph Smith. This is a in Green Township. It is not a far stretch to believe that they may wonderful book on Jedediah Smith and have rented land, share cropped, or operated another general store his family. In Mr. Morgan’s book there and lumber sales that were actually owned by another person. is a note saying that Jedediah S. -

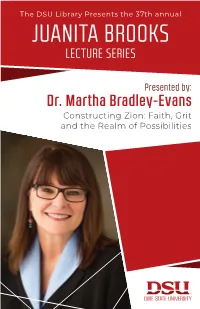

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

Dale Morgan, Writer's Project, and Mormon History As a Regional Study

Dale Morgan, Writer's Project, and Mormon History as a Regional Study Charles S. Peterson AT THE 1968 ANNUAL MEETING of the Utah Historical Society, Juanita Brooks read a paper about the Southern Utah Records Survey of the early and mid-1930s that had been a forerunner to the Federal Writers' Project. She began with a direct and earthy line, "Jest a Copyin — Word fr Word," and concluded with equal directness that the survey had taught her to see each record and to see it whole (Brooks 1969). They were simple lines and understated, but between them and hid- den beyond was an adventure of the mind, a story about the person- alities and events of one of the most exciting intellectual endeavors ever to take place in Mormon country. She spoke that evening about Dixie's poverty, about a king's ransom in pioneer diaries, about discov- ery, collection, and transcription, and about remarkable personal ded- ication. Fortunately Brooks spoke also about friends made along the way. Most notably she praised her long-time colleague and advocate, Dale Morgan, whose work with the Writers' Project was the first step in a remarkable career as a historian of regional topics including state his- tory, mountain men and exploration, and the Mormon experience. This essay will take a look at Dale Morgan in the context of the Utah Records Survey and the Federal Writers' Project, with the intent to know him better and to shed light on regionalism's influence on Mormon history. CHARLES S. PETERSON is a professor emeritus of history at Utah State University, professor of history at Southern Utah University, former editor of the Western Historical Quarterly, and former director of the Utah Historical Society (1969-71). -

Madeline Mcquown, Dale Morgan, and the Great Unfinished Brigham Young Biography

Madeline McQuown, Dale Morgan, and the Great Unfinished Brigham Young Biography Craig L. Foster SHORTLY AFTER COMPLETING THE DEVIL DRIVES: A Life of Sir Richard Burton in 1967, Fawn M. Brodie wrote to her friend Dale Morgan confessing that she had "been periodically haunted by the desire to do a biography of Brigham Young." She mentioned that she had been encouraged by "many people" and "more than one publisher."1 Knowing that Morgan's close friend, Madeline R. McQuown, had been working for a number of years on her own Brigham Young biography, Brodie stated that she had stayed away from Young. However, since "so many years [had] gone by with no" McQuown-written biography, Brodie asked Morgan to "frankly" tell her what the status was of McQuown's long-awaited book.2 Morgan quickly responded that McQuown's manuscript was "sub- stantially complete" and "so massive" that "it may have to be a two-vol- ume work." He reported that McQuown had "done an amazing research job" and that at least one publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, had expressed inter- est.3 Notwithstanding Morgan's praise of McQuown's work and discour- agement of Brodie's interest in Brigham Young, Brodie persisted, ex- plaining that W.W. Norton wanted her to write a biography. Her Utah 1. Brodie to Morgan, 14 Aug. 1967, in Newell G. Bringhurst, "Fawn M. Brodie After No Man Knows My History: A Continuing Fascination for the Latter-day Saints and Mormon His- tory," 14-15, privately circulated, copy in my possession. 2. Ibid. 3. Ibid., 15. -

Introduction to John D. Lee Trial Transcripts

Introduction to John D. Lee Trial Transcripts LaJean Purcell Carruth Two reporters, Adam S. Patterson and Josiah Rogerson, recorded the proceedings of the John D. Lee trials in Pitman shorthand.1 Rogerson and Patterson each recorded the first Lee trial, from jury selection to closing arguments. Patterson made a like record of the second Lee trial. The only extant Rogerson shorthand for the second Lee trial is a single legal plea.2 As independent records of the actual court proceedings, the original Rogerson and Patterson shorthand reports of the first trial largely corroborate and complete each other. And when all their notes are combined, they provide by far the most complete and most accurate record of the John D. Lee trials available. Three contemporary transcripts were made from these shorthand records: the Rogerson transcript, the Boreman transcript, and a partial transcript, probably by Patterson, of the second trial.3 On the surface, the history of the creation of the transcripts—as given by transcribers Josiah Rogerson and Waddington Cook, whom Judge Jacob S. Boreman hired to transcribe Patterson’s shorthand—seems straightforward: (1) Patterson transcribed only the testimony portion of the second trial for Lee’s appeal in early 1877.4 (2) Rogerson began to transcribe his own shorthand into the Rogerson 1 transcript in 1883.5 (3) Judge Boreman, who presided over both Lee trials, desired to publish the trial transcripts for profit. He hired Patterson’s former student, Cook, to transcribe Patterson’s shorthand notes; the result became known as the Boreman transcript.6 Careful analysis of the original shorthand and resulting transcripts reveals a far more complex story. -

Awards Received by University of Utah Press Publications

Awards Received by University of Utah Press Publications 2018 Mormon History Association (MHA) Best Biography Award to Carol Cornwall Madsen for Emmeline B. Wells: An Intimate History Brian McConnell Book Award from the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research to Holly Cusack-McVeigh for Stories Find You, Places Know Wayland D. Hand Prize from the American Folkore Association to Margarita Marin-Dale for Decoding Andean Mythology Ordinary Trauma by Jennifer Sinor was selected as a finalist for the 15 Bytes Book Award for Creative Nonfiction. 2017 Evans Biography Award to Gregory Prince for Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History John Whitmer Historical Association’s Brim Biography Book Award to Gregory Prince for Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History Utah Division of State History Francis Armstrong Madsen Best Book Award to Matthew Garrett for Making Lamanites: Mormons, Native Americans, and the Indian Student Placement Program, 1947-2000 Mormon History Association Best Personal History/Memoir Award to Kerry William Bate for The Women: A Family Story Charles Redd Center Clarence Dixon Taylor Historical Research Award to Jerry Spangler and Donna Spangler for Last Chance Byway: The History of Nine Mile Canyon and Nine Mile Canyon: The Archaeological History of an American Treasure 15 Bytes Book Award for Creative Nonfiction to Immortal for Quite Some Time by Scott Abbott 2016 School for Advanced Research Linda Cordell Prize to Scott G. Ortman for Winds from the North: Tewa Origins and Historical Archaeology Mormon History Association Best First Book Award to David Hall for A Faded Legacy: Amy Brown Lyman and Mormon Women’s Activism, 1872-1959 Best of the Best of University Presses ALA/AAUP to The Mapmakers of New Zion: A Cartographic History of Mormonism by Richard Francaviglia Utah Division of State History Meritorious Book Award to Charles S.