Leonard Arrington, Church Historian: Lessons Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and the Reported Incident on the Stairs

Hales: Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and the Stairs Incident 63 Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and the Reported Incident on the Stairs Brian C. Hales Several authors have written that during the Nauvoo period Emma Smith may have had a violent altercation with Eliza R. Snow, one of Joseph’s plural wives.1 Different narratives of varying credibility are sometimes amalgam- ated and inflated to create a flowing storyline of questionable accuracy. For example, Samuel W. Taylor penned this dramatic account in Nightfall at Nau- voo: Eliza got out of bed, feeling queasy. It was early, the house quiet. Perhaps she’d be sick this morning again. Better go out back to the privy, in case. She stepped from her room just as Joseph’s door opened. He paused a moment looking at her with affection—big, handsome, vital, her husband for time and eternity!—then they came together. She whispered, had he decided what to do? He nodded. They could meet at Sarah Cleveland’s this afternoon to talk it over. Two-thirty. A wild cry, then Emma was upon them with a broom-stick. Joseph staggered back. Emma flailed at Eliza with the heavy stick, calling her names, screaming. Eliza, trying to shield her head with her arms, dashed for the stairs, stumbled, fell headlong, and went head over heels down the steep steps as everything went black. She awakened in bed. Emma was there, and Joseph, together with Dr. Bern- hisel. “Eliza,” Emma said, “I’m sorry. .” “I understand,” Eliza said. Her voice came as a weak whisper. -

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 8 Number 1 Article 14 1996 “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Gary F. Novak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Novak, Gary F. (1996) "“The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol8/iss1/14 This Historical and Cultural Studies is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Gary F. Novak Reference FARMS Review of Books 8/1 (1996): 122–67. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Review of Dale Morgan On Early Mormonism: Correspondence and a New History (1986), edited by John Phillip Walker. John Phillip Walker, ed. Dale Morgan On Early Mor· mOllism: Correspondence and a New History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1986. viii + 414 pp., with bibliography, no index. $20.95 (out of print). Reviewed by Gary F. Novak "The Most Convenient Form of Error": Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon We are onl y critica l about the th ings we don't want to believe. -

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Book Reviews 149 Book Reviews WILL BAGLEY. Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002. xxiv + 493 pp. Illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index. $39.95 hardback.) Reviewed by W. Paul Reeve, assistant professor of history, Southern Virginia University, and Ardis E. Parshall, independent researcher, Orem, Utah. Explaining the violent slaughter of 120 men, women, and children at the hands of God-fearing Christian men—priesthood holders, no less, of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is no easy task. Biases per- meate the sources and fill the historical record with contradictions and polemics. Untangling the twisted web of self-serving testimony, journals, memoirs, government reports, and the like requires skill, forthrightness, integrity, and the utmost devotion to established standards of historical scholarship. Will Bagley, a journalist and independent historian with sever- al books on Latter-day Saint history to his credit, has recently tried his hand at unraveling the tale. Even though Bagley claims to be aware of “the basic rules of the craft of history” (xvi), he consistently violates them in Blood of the Prophets. As a result, Juanita Brooks’ The Mountain Meadows Massacre remains the most definitive and balanced account to date. Certainly there is no justification for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Mormon men along with Paiute allies acted beyond the bounds of reason to murder the Fancher party, a group of California-bound emigrants from Arkansas passing through Utah in 1857. It is a horrific crime, one that Bagley correctly identifies as “the most violent incident in the history of America’s overland trails” (xiii), and it belongs to Utah and the Mormons. -

Ezra Taft B Enso N

Teachings of Presidents of the Ezra Presidents of Church: of Benson Taft Teachings Teachings of Presidents of the Church Ezra Taft Benson TEACHINGS OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH EZRA TAFT BENSON Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Books in the Teachings of Presidents of the Church Series Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (item number 36481) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young (35554) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: John Taylor (35969) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Wilford Woodruff (36315) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Lorenzo Snow (36787) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith (35744) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Heber J. Grant (35970) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: George Albert Smith (36786) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: David O. McKay (36492) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Fielding Smith (36907) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Harold B. Lee (35892) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Spencer W. Kimball (36500) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Ezra Taft Benson (08860) To obtain copies of these books, go to your local distribution center or visit store.ld s.or g. The books are also available at LDS.or g and on the Gospel Library mobile application. Your comments and suggestions about this book would be ap- preciated. Please submit them to Curriculum Development, 50 East North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-0024 USA. Email: cur -development@ ldschurch. org Please give your name, address, ward, and stake. -

The Presidents of the Church the Presidents of the Church

The Presidents of the Church The Presidents of the Church Teacher’s Manual Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 1989, 1993, 1996 by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 2/96 Contents Lesson Number and Title Page Helps for the Teacher v 1 Our Choice to Follow Christ 1 2 The Scriptures—A Sure Guide for the Latter Days 5 3 Revelation to Living Prophets Comes Again to Earth 10 4 You Are Called to Build Zion 14 5 Listening to a Prophet Today 17 6 The Prophet Joseph Smith—A Light in the Darkness 23 7 Strengthening a Testimony of Joseph Smith 28 8 Revelation 32 9 Succession in the Presidency 37 10 Brigham Young—A Disciple Indeed 42 11 Brigham Young: Building the Kingdom by Righteous Works 48 12 John Taylor—Man of Faith 53 13 John Taylor—Defender of the Faith 57 14 A Missionary All Your Life 63 15 Wilford Woodruff—Faithful and True 69 16 Wilford Woodruff: Righteousness and the Protection of the Lord 74 17 Lorenzo Snow Served God and His Fellowmen 77 18 Lorenzo Snow: Financing God’s Kingdom 84 19 Make Peer Pressure a Positive Experience 88 20 Joseph F. Smith—A Voice of Courage 93 21 Joseph F. Smith: Redemption of the Dead 98 22 Heber J. Grant—Man of Determination 105 23 Heber J. Grant: Success through Reliance on the Lord 110 24 Turning Weaknesses and Trials into Strengths 116 25 George Albert Smith: Responding to the Good 120 26 George Albert Smith: A Mission of Love 126 27 Peace in Troubled Times 132 iii 28 David O. -

The Return of Oliver Cowdery

The Return of Oliver Cowdery Scott H. Faulring On Sunday, 12 November 1848, apostle Orson Hyde, president of the Quorum of the Twelve and the church’s presiding ofcial at Kanesville-Council Bluffs, stepped into the cool waters of Mosquito Creek1 near Council Bluffs, Iowa, and took Mormonism’s estranged Second Elder by the hand to rebaptize him. Sometime shortly after that, Elder Hyde laid hands on Oliver’s head, conrming him back into church membership and reordaining him an elder in the Melchizedek Priesthood.2 Cowdery’s rebaptism culminated six years of desire on his part and protracted efforts encouraged by the Mormon leadership to bring about his sought-after, eagerly anticipated reconciliation. Cowdery, renowned as one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon, corecipient of restored priesthood power, and a founding member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had spent ten and a half years outside the church after his April 1838 excommunication. Oliver Cowdery wanted reafliation with the church he helped organize. His penitent yearnings to reassociate with the Saints were evident from his personal letters and actions as early as 1842. Oliver understood the necessity of rebaptism. By subjecting himself to rebaptism by Elder Hyde, Cowdery acknowledged the priesthood keys and authority held by the First Presidency under Brigham Young and the Twelve. Oliver Cowdery’s tenure as Second Elder and Associate President ended abruptly when he decided not to appear and defend himself against misconduct charges at the 12 April -

Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Arrington Annual Lecture Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures 9-24-2015 Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman Quincy D. Newell Hamilton College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/arrington_lecture Part of the History Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Newell, Quincy D., "Narrating Jane: Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman" (2015). 21st annual Arrington Lecture. This Lecture is brought to you for free and open access by the Leonard J. Arrington Mormon History Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arrington Annual Lecture by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LEONARD J. ARRINGTON MORMON HISTORY LECTURE SERIES No. 21 Narrating Jane Telling the Story of an Early African American Mormon Woman by Quincy D. Newell September 24, 2015 Sponsored by Special Collections & Archives Merrill-Cazier Library Utah State University Logan, Utah Newell_NarratingJane_INT.indd 1 4/13/16 2:56 PM Arrington Lecture Series Board of Directors F. Ross Peterson, Chair Gary Anderson Philip Barlow Jonathan Bullen Richard A. Christenson Bradford Cole Wayne Dymock Kenneth W. Godfrey Sarah Barringer Gordon Susan Madsen This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-1-60732-561-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60732-562-8 (ebook) Published by Merrill-Cazier Library Distributed by Utah State University Press Logan, UT 84322 Newell_NarratingJane_INT.indd 2 4/13/16 2:56 PM Foreword F. -

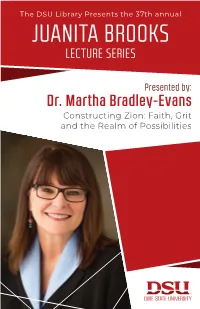

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

Ezra Taft Benson

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 9 Number 1 Article 12 4-1-2008 Profiles of the Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson John P. Livingstone [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Livingstone, John P. "Profiles of the Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 9, no. 1 (2008). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol9/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Profiles of the Prophets: Ezra Taft Benson John P. Livingstone John P. Livingstone ([email protected]) is an associate professor of Church history at Brigham Young University. The last few years of President Spencer W. Kimball’s life were fraught with poor health and diminished strength. When Ezra Taft Benson received the phone call announcing the death of the venerable old prophet, he was stricken with grief and reverence for the heavy task that now fell on him. On the Sunday following President Kimball’s death, November 10, 1985, the Quorum of the Twelve met in the Salt Lake Temple at three in the afternoon. During this most solemn of assemblies, Presi- dent Benson asked Gordon B. Hinckley and Thomas S. Mon- son to serve as his counselors. President Howard W. Hunter, next in seniority, set apart Ezra Taft Benson as President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

Joseph Smith Sex Offender?

Recovery Board : RfM Recovery from Mormonism (RfM) discussion forum. Joseph Smith: The Founding Sex Fiend of Posted by: steve benson ( ) Mormonism (5 Exhibits) Date: October 26, 2015 02:34PM EXHIBIT A: Joseph Smith's "Revelation" on Polygamy was Expressly Designed by Him to Facilitate Him Having Sex with His Multiple Wives In a past thread, RfM poster "ness" stated: "Well, this is a new TBM explanation; There is no solid evidence that JS married other men's wives or children under 18 years old. "Heard this one before? Or is this TBM just totally wrapped up in his delusions? From what I gather, most TBMs accept that Joseph Smith married other mens wives and young girls. "Asking for 'solid proof' (what else does he want? Joseph Smith to appear to him personally saying he banged other mens wives?) while the whole church is based on a boy who claimed he saw God. There is no SOLID proof of Joseph Smith claims, no proof of the Book of Mormon , no proof of the Church's claims, and that's good enough for a TBM because they 'know it's true.'" ("There's NO SOLID proof," posted by "ness," on "Recovery from Mormnmism" discussion board, 7 February 2914, at:http://exmormon.org/phorum/read.php? 2,1162992,1162992#msg-1162992) RfM poster "Deconstructor's" research flatly contradicts such true-believing hogwash. From his own examination of the topic: "'Did Joseph Smith Have Sex with His Wives?' "1. Did Joseph Smith Have More Than One Wife While He Was Alive? "Absolutely. Just check Joseph Smith's official Church marriage record at www.familysearch.org [reportedly no longer available].