Introduction to John D. Lee Trial Transcripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 8 Number 1 Article 14 1996 “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Gary F. Novak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Novak, Gary F. (1996) "“The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol8/iss1/14 This Historical and Cultural Studies is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Gary F. Novak Reference FARMS Review of Books 8/1 (1996): 122–67. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Review of Dale Morgan On Early Mormonism: Correspondence and a New History (1986), edited by John Phillip Walker. John Phillip Walker, ed. Dale Morgan On Early Mor· mOllism: Correspondence and a New History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1986. viii + 414 pp., with bibliography, no index. $20.95 (out of print). Reviewed by Gary F. Novak "The Most Convenient Form of Error": Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon We are onl y critica l about the th ings we don't want to believe. -

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Book Reviews 149 Book Reviews WILL BAGLEY. Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002. xxiv + 493 pp. Illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index. $39.95 hardback.) Reviewed by W. Paul Reeve, assistant professor of history, Southern Virginia University, and Ardis E. Parshall, independent researcher, Orem, Utah. Explaining the violent slaughter of 120 men, women, and children at the hands of God-fearing Christian men—priesthood holders, no less, of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is no easy task. Biases per- meate the sources and fill the historical record with contradictions and polemics. Untangling the twisted web of self-serving testimony, journals, memoirs, government reports, and the like requires skill, forthrightness, integrity, and the utmost devotion to established standards of historical scholarship. Will Bagley, a journalist and independent historian with sever- al books on Latter-day Saint history to his credit, has recently tried his hand at unraveling the tale. Even though Bagley claims to be aware of “the basic rules of the craft of history” (xvi), he consistently violates them in Blood of the Prophets. As a result, Juanita Brooks’ The Mountain Meadows Massacre remains the most definitive and balanced account to date. Certainly there is no justification for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Mormon men along with Paiute allies acted beyond the bounds of reason to murder the Fancher party, a group of California-bound emigrants from Arkansas passing through Utah in 1857. It is a horrific crime, one that Bagley correctly identifies as “the most violent incident in the history of America’s overland trails” (xiii), and it belongs to Utah and the Mormons. -

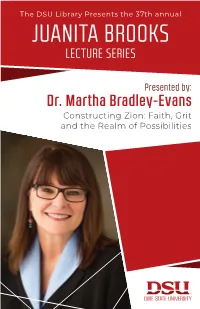

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

Awards Received by University of Utah Press Publications

Awards Received by University of Utah Press Publications 2018 Mormon History Association (MHA) Best Biography Award to Carol Cornwall Madsen for Emmeline B. Wells: An Intimate History Brian McConnell Book Award from the International Society for Contemporary Legend Research to Holly Cusack-McVeigh for Stories Find You, Places Know Wayland D. Hand Prize from the American Folkore Association to Margarita Marin-Dale for Decoding Andean Mythology Ordinary Trauma by Jennifer Sinor was selected as a finalist for the 15 Bytes Book Award for Creative Nonfiction. 2017 Evans Biography Award to Gregory Prince for Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History John Whitmer Historical Association’s Brim Biography Book Award to Gregory Prince for Leonard Arrington and the Writing of Mormon History Utah Division of State History Francis Armstrong Madsen Best Book Award to Matthew Garrett for Making Lamanites: Mormons, Native Americans, and the Indian Student Placement Program, 1947-2000 Mormon History Association Best Personal History/Memoir Award to Kerry William Bate for The Women: A Family Story Charles Redd Center Clarence Dixon Taylor Historical Research Award to Jerry Spangler and Donna Spangler for Last Chance Byway: The History of Nine Mile Canyon and Nine Mile Canyon: The Archaeological History of an American Treasure 15 Bytes Book Award for Creative Nonfiction to Immortal for Quite Some Time by Scott Abbott 2016 School for Advanced Research Linda Cordell Prize to Scott G. Ortman for Winds from the North: Tewa Origins and Historical Archaeology Mormon History Association Best First Book Award to David Hall for A Faded Legacy: Amy Brown Lyman and Mormon Women’s Activism, 1872-1959 Best of the Best of University Presses ALA/AAUP to The Mapmakers of New Zion: A Cartographic History of Mormonism by Richard Francaviglia Utah Division of State History Meritorious Book Award to Charles S. -

The Rise of Mormon Cultural History and the Changing Status of the Archive

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 The rise of Mormon cultural history and the changing status of the archive Joseph M. Spencer San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Spencer, Joseph M., "The rise of Mormon cultural history and the changing status of the archive" (2009). Master's Theses. 3729. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.umb6-v8ux https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3729 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF MORMON CULTURAL HISTORY AND THE CHANGING STATUS OF THE ARCHIVE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Library and Information Science San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Library and Information Science by Joseph M. Spencer August 2009 UMI Number: 1478575 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1478575 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Full Issue BYU Studies

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 53 | Issue 3 Article 1 9-1-2014 Full Issue BYU Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Studies, BYU (2014) "Full Issue," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 53 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol53/iss3/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Advisory Board Alan L. Wilkins, chairStudies: Full Issue James P. Bell Donna Lee Bowen Douglas M. Chabries Doris R. Dant R. Kelly Haws Editor in Chief John W. Welch Church History Board Richard Bennett, chair 19th-century history Brian Q. Cannon 20th-century history Kathryn Daynes 19th-century history Gerrit J. Dirkmaat Involving Readers Joseph Smith, 19th-century Mormonism Steven C. Harper in the Latter-day Saint documents Academic Experience Frederick G. Williams cultural history Liberal Arts and Sciences Board Barry R. Bickmore, co-chair geochemistry Eric Eliason, co-chair English, folklore David C. Dollahite faith and family life Susan Howe English, poetry, drama Neal Kramer early British literature, Mormon studies Steven C. Walker Christian literature Reviews Board Eric Eliason, co-chair English, folklore John M. Murphy, co-chair Mormon and Western Trevor Alvord new media Herman du Toit art, museums Angela Hallstrom literature Greg Hansen music Emily Jensen new media Megan Sanborn Jones theater and media arts Gerrit van Dyk Church history Specialists Casualene Meyer poetry editor Thomas R. -

Leonard Arrington, Church Historian: Lessons Learned

THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES presents The 34th Annual Lecture LEONARD ARRINGTON, CHURCH HISTORIAN: Lessons Learned by Gregory A. Prince, Ph.D St. George Tabernacle February 16, 2017 7:00 P.M. Co-sponsored by Dixie State University Library St. George, Utah and the Obert C. Tanner Foundation This page intentionally blank Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consent, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwaver- ing courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. Copyright 2018, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770 All rights reserved Gregory A. Prince was born in Santa Monica, California in 1948, but his familial roots are embedded deeply in the red sand of Southern Utah, with five generations of his ancestors, beginning with George Prince in the 1860s, having pioneered and lived in St. George and New Harmony. Dr. Prince enrolled in Dixie Junior College in 1965 and graduated as valedictorian in 1967. After a two-year proselytizing mission for the LDS Church in Brazil, he enrolled in the UCLA School of Dentistry, graduat- ing as valedictorian in 1973. He remained at UCLA for two additional years of Gregory A. -

Monuments and Massacre: the Art of Remembering

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2006 Monuments and Massacre: The Art of Remembering Lafe Gerald Conner Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Conner, Lafe Gerald, "Monuments and Massacre: The Art of Remembering" (2006). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 714. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/714 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MONUMENTS AND MASSACRE: THE ART OF REMEMBERING by Lafe Gerald Conner Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENT HONORS in History Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Department Honors Advisor Chris Conte Sue Shapiro Director of Honors Program Christie Fox UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT 2006 Monuments and Massacre The Art of Remembering Lafe Conner Honors Thesis April 26, 2006 "What else is there, after all, besides memory and dreams, and the way they mix with land and air and water to make us all whole? " 1 Robert Michael Pyle. I Rain transfonned the dusty trail outside our trailer into a highway of sediments speeding and settling. Inside the trailer I pulled on my boots and raincoat while my dad slipped into a larger version of his own . Then, with my two brothers , we embarked in puddle play. Aimed at impeding the torrent , we employed any object; rocks, branches, wood chips, even our own wet boots and hands . -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 16, 1990

Journal of Mormon History Volume 16 Issue 1 Article 1 1990 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 16, 1990 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (1990) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 16, 1990," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol16/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 16, 1990 Table of Contents • --The Power Of Place and the Spirit of Locale: Finding God on Western Trails Stanley B. Kimball, 3 • --Fawn M. Brodie, "Mormondom's Lost Generation," and No Man Knows My History Newell G. Bringhurst, 11 • --Remembering Nauvoo: Historiographical Considerations Glen M. Leonard, 25 • --The Nauvoo Heritage of the Reorganized Church Richard P. Howard, 41 • --Mormon Nauvoo from a Non-Mormon Perspective John E. Hallwas, 53 • --The Significance of Nauvoo for Latter-day Saints Ronald K. Esplin, 71 • --Learning to Play: The Mormon Way and the Way of Other Americans R. Laurence Moore, 89 This full issue is available in Journal of Mormon History: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol16/iss1/ 1 Journal of Mormon History VOLUME 16, 1990 Editorial Staff LOWELL M. DURHAM, JR., Editor ELEANOR KNOWLES, Associate Editor MARTHA SONNTAG BRADLEY, Associate Editor JACK M. LYON, Associate Editor KENT WARE, Designer PATRICIA J. -

NHD Project Guidebook

Rio Grande Depot | 5.7 | March 18, 2020 NHD UTAH PROJECT GUIDEBOOK 2020-21 __________________________ Communication in History: The Key to Understanding CONTENTS Getting Started FAQs .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Annual Planning Calendar ........................................................................................................ 5 Divisions & Categories ............................................................................................................. 6 History Day Roadmap ............................................................................................................... 7 Breaking it Down ..................................................................................................................... 8 NHD Judging Criteria ................................................................................................................ 9 Theme & Topic 2021 Annual Theme .................................................................................................................. 11 Right-Sizing Your Topic ........................................................................................................... 12 Utah History Topic Ideas ..................................................................................................... 13-14 Topic Proposal Form ............................................................................................................... 15 Do Your Research