Monuments and Massacre: the Art of Remembering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Review of at Sword's Point, Part 1: a Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858

Mormon Studies Review Manuscript 1105 Review of At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858; At Sword’s Point, Part 2: A Documentary History of the Utah War, 1858-1859, edited by William P. MacKinnon. Brent M. Rogers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr2 Part of the Mormon Studies Commons Rogers: Review of At Sword’s Point, Part 1: Title Review of At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858; At Sword’s Point, Part 2: A Documentary History of the Utah War, 1858-1859, by William P. MacKinnon. edited Author Brent M. Rogers Reference Mormon Studies Review (201 ): 126 131. ISSN 2156-8022 (print), 2156-80305 8 (online)– DOI https://doi.org/10.18809/msr.2018.0117 Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1 Submission to Mormon Studies Review 126 Mormon Studies Review wins but instead how different peoples are made vulnerable by each new adjustment. Neil J. Young is an Affiliated Research Scholar with the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University. He is the author of We Gather Together: The Religious Right and theProblem of Interfaith Politics (Oxford, 2015). William P. MacKinnon, ed. At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858. Vol. 10 of the series Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier, edited by Will Bagley. Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2008. William P. MacKinnon, ed. At Sword’s Point, Part 2: A Documentary History of the Utah War, 1858–1859. -

Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 8 Number 1 Article 14 1996 “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Gary F. Novak Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Novak, Gary F. (1996) "“The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol8/iss1/14 This Historical and Cultural Studies is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title “The Most Convenient Form of Error”: Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Gary F. Novak Reference FARMS Review of Books 8/1 (1996): 122–67. ISSN 1099-9450 (print), 2168-3123 (online) Abstract Review of Dale Morgan On Early Mormonism: Correspondence and a New History (1986), edited by John Phillip Walker. John Phillip Walker, ed. Dale Morgan On Early Mor· mOllism: Correspondence and a New History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1986. viii + 414 pp., with bibliography, no index. $20.95 (out of print). Reviewed by Gary F. Novak "The Most Convenient Form of Error": Dale Morgan on Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon We are onl y critica l about the th ings we don't want to believe. -

A Tangled Skein

A Tangled Skein a Tangled Skein A Companion Volume to The Baker Street Irregulars’ Expedition to The Country of the Saints Edited by Leslie S. Klinger New York The Baker Street Irregulars 2008 Conan Doyle Was Right Danites,Avenging Angels,and Holy Murder in the Mormon West WILL BAGLEY “Who controls the past,” ran the Party slogan, “controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.” And yet the past, though of its nature alterable, never had been altered. Whatever was true now was true from everlasting to everlasting. It was quite simple. All that was needed was an unending series of victories over your own memory. — George Orwell, 1984. S a native-born son of Utah and a fifth-generation Latter-day Saint, I am A honored to welcome the Baker Street Irregulars to our fair city on the Great Salt Lake and to the hallowed halls of the Alta Club. While I al- ways strive to be a gentleman and a scholar, I am going to relax my usual meticu- lous erudite standards in this paper in the hope of sharing some of the fun I have with Utah history. I am also going to take off the gloves and engage in some his- torical hand-to-hand combat. As my friend and colleague — and your fellow Irregular, “Enoch J. Drebber,” has pointed out so effectively in his paper later in this volume, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle visited Utah for the first time in 1923 to share his religious convictions with the Mormons, a population whose deeply held faith was as controversial and unortho- dox as his own. -

WRESTLING BRIGHAM in the Remaining Sixty Pages, Bagley Dis- Cusses the Fate of Such Massacre Planners Or Participants As Isaac C

62-65_briggs_botp_review.qxd 12/23/02 11:36 AM Page 62 SUNSTONE was convicted in the second and was ulti- BOOK REVIEW mately executed by firing squad in early 1877, the same year Brigham Young died. More than a third of the narrative deals with the events of this twenty-year period. WRESTLING BRIGHAM In the remaining sixty pages, Bagley dis- cusses the fate of such massacre planners or participants as Isaac C. Haight, Philip BLOOD OF THE PROPHETS:BRIGHAM YOUNG Klingensmith, John M. Higbee, and William AND THE MASSACRE AT MOUNTAIN MEADOWS H. Dame, all of whom died between 1880 and 1910. He briefly treats the contributions by Will Bagley of massacre commentators such as Josiah University of Oklahoma Press, 2002 Gibbs, Josiah Rogerson, Orson Whitney, and 493 pages, $39.95 Robert Baskin. And he highlights the final years of the last of the militia participants and the Fancher party’s surviving children. Reviewed by Robert H. Briggs In the final chapter and epilogue, Bagley recounts Juanita Brooks’s courageous revela- tion of the details of the massacre in the early 1950s, the tentative efforts toward reconcilia- tion between descendants of the Arkansas Historian Will Bagley identifies the victims, train and of southern Utah militiamen in- heroes, and villains of the Mountain cluding John D. Lee, and the successive placing of monuments in 1990 and 1999 at Meadows massacre, but focuses especially the Mountain Meadows massacre site as on the question, “What did Brigham Young more fitting remembrances of the dead. Here and earlier, as he pays respect and know and when did he know it?” acknowledges intellectual debts, Bagley praises Brooks as one of the West’s “best and bravest historians” (xiii) and announces that Y DUSK ON Friday, 11 September tury has brought the conditions that sur- his work “is not a revision but an extension 1857, the massacre at Mountain round horrific massacres into sharper focus. -

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Book Reviews 149 Book Reviews WILL BAGLEY. Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002. xxiv + 493 pp. Illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index. $39.95 hardback.) Reviewed by W. Paul Reeve, assistant professor of history, Southern Virginia University, and Ardis E. Parshall, independent researcher, Orem, Utah. Explaining the violent slaughter of 120 men, women, and children at the hands of God-fearing Christian men—priesthood holders, no less, of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is no easy task. Biases per- meate the sources and fill the historical record with contradictions and polemics. Untangling the twisted web of self-serving testimony, journals, memoirs, government reports, and the like requires skill, forthrightness, integrity, and the utmost devotion to established standards of historical scholarship. Will Bagley, a journalist and independent historian with sever- al books on Latter-day Saint history to his credit, has recently tried his hand at unraveling the tale. Even though Bagley claims to be aware of “the basic rules of the craft of history” (xvi), he consistently violates them in Blood of the Prophets. As a result, Juanita Brooks’ The Mountain Meadows Massacre remains the most definitive and balanced account to date. Certainly there is no justification for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Mormon men along with Paiute allies acted beyond the bounds of reason to murder the Fancher party, a group of California-bound emigrants from Arkansas passing through Utah in 1857. It is a horrific crime, one that Bagley correctly identifies as “the most violent incident in the history of America’s overland trails” (xiii), and it belongs to Utah and the Mormons. -

Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows Will Bagley

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 42 Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-2003 Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows Will Bagley Thomas G. Alexander Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Alexander, Thomas G. (2003) "Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows Will Bagley," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 42 : Iss. 1 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol42/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Alexander: <em>Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Moun will bagley blood of the prophets Bpighambrigham young and the massacre at mountain meadows norman university of oklahoma press 2002 reviewed by thomas G alexander he massacre at mountain meadows remains one of the most heinous Ttheand least understood crimes in the history of the american west how a militia unit of god fearing christians could have murdered more than 120 people in cold blood seems beyond comprehension in a previous book I1 attempted to understand the massacre by comparing it to the mas- sacres of christian armeniansArmenians by moslem turks of jews by christian ger mans and ofmoslem bosniansBosnians by christian serbsgerbs 11I1 did not say as bagley flippantly claims -

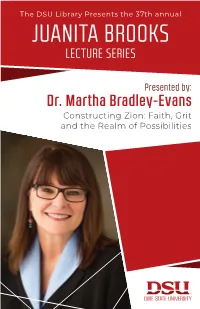

Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The DSU Library Presents the 37th annual JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES Presented by: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit and the Realm of Possibilities THE JUANITA BROOKS LECTURE SERIES PRESENTS THE 37TH ANNUAL LECTURE APRIL 1, 2020 DIXIE STATE UNIVERSITY Constructing Zion: Faith, Grit, and the Realm of Possibilities By: Dr. Martha Bradley-Evans Copyright 2020, Dixie State University St. George, Utah 84770. All rights reserved 2 3 Juanita Brooks Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author. She is recognized, by scholarly consensus, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been lifelong friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her work through this lecture series. Dixie State University and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner family. 5 the Honorary AIA Award from AIA Utah. In 2014 the Outstanding Achievement Award from the YWCA and was made a fellow of the Utah State Historical Society. She is the past vice chair of the Utah State Board of History, a former chair of the Utah Heritage Foundation. Dr. Bradley’s numerous publications include: Kidnapped from that Land: The Government Raids on the Short Creek Polygamists; The Four Zinas: Mothers and Daughters on the Frontier; Pedastals and Podiums: Utah Women, Religious Authority and Equal Rights; Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet, 1839- 1844; Plural Wife: The Autobiography of Mabel Finlayson Allred, and Glorious in Persecution: Joseph Smith, American Prophet 1839-44 among others. -

Evaluating Robert Remini's Joseph Smith and Will Bagley's Brigham Youngs

A Biographer's Burden: Evaluating Robert Remini's Joseph Smith and Will Bagley's Brigham Youngs Newell G. Bringhurst DURING THE PAST YEAR, I have had the opportunity to read and review two sig- nificant books Robert Remini's Joseph Smith (New York: Viking Press, 2003) and Will Bagley's Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Mas- sacre at Mountain Meadows (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002). The two reviews—one for each book and each for a different publication—were extremely brief and perfunctory due to space limitations. This prevented me from doing full justice to the books, and I wish to rectify that now. I confess from the onset that I am favorably impressed with both. Both provide fresh, il- luminating insights into their principal subjects, Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, thereby advancing the craft of Mormon biography, although I do find deficiencies in both works. The books have received nationwide attention, in- cluding reviews in such prestigious publications as the New York Times and the New York Review of Books.2 Such widespread notice would seem to suggest a coming-of-age for Mormon historical scholarship. Indeed, the fact that non-Mormon Robert Remini, a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and a nationally renowned Jacksonian scholar, would choose to write on Joseph Smith lends credence to such a coming of age. Remini is known for his definitive multi-volume biogra- phy of President Andrew Jackson, and he is a winner of the National Book Award. He has produced a compelling and, on the whole, sympathetic biogra- 1. -

Blood and Thunder

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library THE RUNAWAY OFFICIALS REVISITED: REMAKING THE MORMON IMAGE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA by Bruce W. Worthen A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History The University of Utah May 2012 Copyright © Bruce W. Worthen 2012 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The thesis of Bruce W. Worthen has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: W. Paul Reeve , Chair March 2, 2012 Date Approved Edward Davies, II , Member March 2, 2012 Date Approved L. Ray Gunn , Member March 2, 2012 Date Approved and by Isabel Moreira , Chair of the Department of History and by Charles A. Wight, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT In September of 1851, four federal officials left Utah Territory after serving less than four months. Chief Justice Lemuel G. Brandebury, Associate Justice Perry E. Brocchus, Territorial Secretary Broughton D. Harris, and Indian Subagent Henry R. Day created a furor in Congress with their reports of Brigham Young‘s rebellion against federal authority. This came as a great surprise in Washington since over the previous five years, Mormon agents had created an image of the Latter-day Saints as mainstream Americans who were loyal to the United States and had a conventional form of republican government. Unfortunately, the Compromise of 1850 resulted in Congress imposing an unwanted territorial government on the Mormons. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

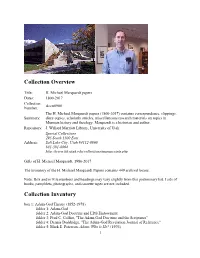

Collection Inventory Box 1: Adam-God Theory (1852-1978) Folder 1: Adam-God Folder 2: Adam-God Doctrine and LDS Endowment Folder 3: Fred C

Collection Overview Title: H. Michael Marquardt papers Dates: 1800-2017 Collection Accn0900 Number: The H. Michael Marquardt papers (1800-2017) contains correspondence, clippings, Summary: diary copies, scholarly articles, miscellaneous research materials on topics in Mormon history and theology. Marquardt is a historian and author. Repository: J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah Special Collections 295 South 1500 East Address: Salt Lake City, Utah 84112-0860 801-581-8864 http://www.lib.utah.edu/collections/manuscripts.php Gifts of H. Michael Marquardt, 1986-2017 The inventory of the H. Michael Marquardt Papers contains 449 archival boxes. Note: Box and/or File numbers and headings may vary slightly from this preliminary list. Lists of books, pamphlets, photographs, and cassette tapes are not included. Collection Inventory box 1: Adam-God Theory (1852-1978) folder 1: Adam-God folder 2: Adam-God Doctrine and LDS Endowment folder 3: Fred C. Collier, "The Adam-God Doctrine and the Scriptures" folder 4: Dennis Doddridge, "The Adam-God Revelation Journal of Reference" folder 5: Mark E. Peterson, Adam: Who is He? (1976) 1 folder 6: Adam-God Doctrine folder 7: Elwood G. Norris, Be Not Deceived, refutation of the Adam-God theory (1978) folder 8-16: Brigham Young (1852-1877) box 2: Adam-God Theory (1953-1976) folder 1: Bruce R. McConkie folder 2: George Q. Cannon on Adam-God folder 3: Fred C. Collier, "Gospel of the Father" folder 4: James R. Clark on Adam folder 5: Joseph F. Smith folder 6: Joseph Fielding Smith folder 7: Millennial Star (1853) folder 8: Fred C. Collier, "The Mormon God" folder 9: Adam-God Doctrine folder 10: Rodney Turner, "The Position of Adam in Latter-day Saint Scripture" (1953) folder 11: Chris Vlachos, "Brigham Young's False Teaching: Adam is God" (1979) folder 12: Adam-God and Plurality of Gods folder 13: Spencer W.