David O. Mckay S Confrontation with Communism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

The Keys That Never Rust

The Keys That Never Rust Elder James E. Faust Of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles Ensign, Nov. 1994, 72-74 A few months ago, my beloved Ruth, Elder Holland very much, saying in substance, ‘Now, if they kill me, and his sweet Patty, and I accompanied a group into the you have all the keys and all the ordinances and you can fascinating old city of Jerusalem to look for the door confer them upon others, and the powers of Satan will with the name of Hyde carved on it. The enchanting not be able to tear down the kingdom as fast as you will smells of the open containers of spices and the sounds of be able to build it up, and upon your shoulders will the men selling their wares were exhilarating. As we entered responsibility of leading this people rest.’ ” (Joseph St. Saviour’s Monastery, looking for the door, we Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, comp. Bruce R. entered into old passageways surrounded by stone walls. McConkie, 3 vols. [Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954–56], We were told that some parts of the walls went back to 1:259) the time of the Crusaders. On one wall hung an After learning of the deaths of the Prophet Joseph assortment of ancient rusted keys. Some of these keys and the Patriarch Hyrum, Wilford Woodruff reports his were huge. All were larger than the keys we use today. meeting with Brigham Young, who was then the Many of them were very ornate. Many of the doors the President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, as keys were made to open no longer exist, or if they do, the follows: “I met Brigham Young in the streets of Boston, keys and the locks would be too rusty to open them. -

Professionalization of the Church Historian's Office

“There Shall Be A Record Kept Among You:” Professionalization of the Church Historian’s Office J. Gordon Daines III University Archivist Brigham Young University Slide 1: The archival profession came into its own in the 20th century. This trend is reflected nationally with the development of the National Archives and the establishment of the Society of American Archivists. The National Archives provided evidence of the value of trained staff and the Society of American Archivists reached out to records custodians across the country to help them professionalize their skills. National trends were reflected locally across the country. This presentation examines what it means to be a profession and how the characteristics of a profession began to manifest themselves in the Church Historian’s Office of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It also examines how the recordkeeping practices of the Church influenced acceptance of professionalization. Professionalization and American archives Slide 2: It is not easy to define what differentiates an occupation from a profession. Sociologists who study the professions have described a variety of characteristics of professions but have generated very little consensus on which of these characteristics are the fundamental criteria for defining a profession.1 As Stan Lester has noted “the notion of a ‘profession’ as distinct from a ‘non-professional’ occupation is far from clear."2 In spite of this lack of clarity about what defines a profession, it is still useful to attempt to distill a set of criteria for defining what a profession is. This is particularly true when studying occupations that are attempting to gain status as a profession. -

Download the Full Magazine (16.7Mb)

b Spring/Summer 2018 • Law Quadrangle OPENING 5 Quotes You’ll See… …In This Issue of the Law Quadrangle 1. “ In many ways, juries are more ready than the law to hold cybercriminals accountable. Jurors understand we aren’t living in a puritanical world anymore and this kind of conduct isn’t acceptable.” (p. 16) 2. “ Between the ideological poles is the big middle ground of Americans who believe climate change is an issue and want something done about it. And they’re willing to support getting their energy from renewable sources—especially now that it doesn’t cost more.” (p. 31) 3. “ Entering law school, I didn’t think I would be advising art and design students on how to make steam more imaginative, but I did and it was really fun.” (p. 50) Law Quadrangle 4. “ I suspect that I am the only person who went to jail directly as a result of having the privilege to study at Michigan Law • Spring/Summer 2018 School.” (p. 65) 5. “I was a junior associate at Jones Day with no real background in immigration law, but I couldn’t stand by knowing this person would face certain persecution and possibly death if she were forced to leave the United States.” (p. 84) 1 06 A MESSAGE FROM DEAN WEST 0 8 BRIEFS 10 Senior Day 12 Student Scholarship Banquets 14 IN PRACTICE 14 A Case of Five-Ring Fever 16 Bringing Cybercrimes to Justice and the Law up to Speed 17 Opportunity and Complexity in the Middle East 18 COVER STORY 18 The Legal Climate of Climate Change 46 FEATURES 46 Navigating a Sea Change 48 Paradise Found 50 @UMICHLAW 50 Linking Detroit’s Small Businesses with U-M Resources 52 Does v. -

The Ideology of the John Birch Society

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-1966 The Ideology of the John Birch Society Max P. Peterson Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Peterson, Max P., "The Ideology of the John Birch Society" (1966). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7982. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7982 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THEIDEOLOGY OFTHE JOHN BIRCH SOCIETY by Y1ax P. Peterson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTEROF SCIENCE in Political Science Approved: Major Professor Head of Department Dean of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 1966 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to Dr. Milton C. Abrams for the many hours of consultation and direction he provided throughout this study. To Dr. M. Judd Harmon, I express thanks, not only for his constructive criticism on this work, but for the constant challenge he offers as a teacher. A very special thanks is given my wife, Karen, for her countless hours of typing, but first and foremost for the encouragement, u nderstanding, and devotion that she has given me throu ghout my graduate studies. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter I. The Background and Organization of the John Birch Society 4 The Beginning 4 The Symbol 7 The Founder 15 Plan of Action 21 Organizational Mechanics 27 Chapter II. -

Ezra Taft B Enso N

Teachings of Presidents of the Ezra Presidents of Church: of Benson Taft Teachings Teachings of Presidents of the Church Ezra Taft Benson TEACHINGS OF PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH EZRA TAFT BENSON Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Books in the Teachings of Presidents of the Church Series Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (item number 36481) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Brigham Young (35554) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: John Taylor (35969) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Wilford Woodruff (36315) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Lorenzo Snow (36787) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith (35744) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Heber J. Grant (35970) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: George Albert Smith (36786) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: David O. McKay (36492) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Fielding Smith (36907) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Harold B. Lee (35892) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Spencer W. Kimball (36500) Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Ezra Taft Benson (08860) To obtain copies of these books, go to your local distribution center or visit store.ld s.or g. The books are also available at LDS.or g and on the Gospel Library mobile application. Your comments and suggestions about this book would be ap- preciated. Please submit them to Curriculum Development, 50 East North Temple Street, Salt Lake City, UT 84150-0024 USA. Email: cur -development@ ldschurch. org Please give your name, address, ward, and stake. -

President Joseph Fielding Smith, a Dedicated Servant in the Lord's

President Joseph Fielding Smith, a dedicated servant in the Lord’s kingdom 116 CHAPTER 8 The Church and Kingdom of God “Let all men know assuredly that this is the Lord’s Church and he is directing its affairs. What a privilege it is to have membership in such a divine institution!” From the Life of Joseph Fielding Smith Joseph Fielding Smith’s service as President of the Church, from January 23, 1970, to July 2, 1972, was the culmination of a lifetime of dedication in the Lord’s kingdom. He joked that his first Church assignment came when he was a baby. When he was nine months old, he and his father, President Joseph F. Smith, accompanied Pres- ident Brigham Young to St. George, Utah, to attend the dedication of the St. George Temple.1 As a young man, Joseph Fielding Smith served a full-time mis- sion and was later called to be president in a priesthood quorum and a member of the general board of the Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association (the forerunner to today’s Young Men organization). He also worked as a clerk in the Church Historian’s office, and he quietly helped his father as an unofficial secretary when his father was President of the Church. Through these ser- vice opportunities, Joseph Fielding Smith came to appreciate the Church’s inspired organization and its role in leading individuals and families to eternal life. Joseph Fielding Smith was ordained an Apostle of the Lord Jesus Christ on April 7, 1910. He served as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles for almost 60 years, including almost 20 years as President of that Quorum. -

The Presidents of the Church the Presidents of the Church

The Presidents of the Church The Presidents of the Church Teacher’s Manual Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah © 1989, 1993, 1996 by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 2/96 Contents Lesson Number and Title Page Helps for the Teacher v 1 Our Choice to Follow Christ 1 2 The Scriptures—A Sure Guide for the Latter Days 5 3 Revelation to Living Prophets Comes Again to Earth 10 4 You Are Called to Build Zion 14 5 Listening to a Prophet Today 17 6 The Prophet Joseph Smith—A Light in the Darkness 23 7 Strengthening a Testimony of Joseph Smith 28 8 Revelation 32 9 Succession in the Presidency 37 10 Brigham Young—A Disciple Indeed 42 11 Brigham Young: Building the Kingdom by Righteous Works 48 12 John Taylor—Man of Faith 53 13 John Taylor—Defender of the Faith 57 14 A Missionary All Your Life 63 15 Wilford Woodruff—Faithful and True 69 16 Wilford Woodruff: Righteousness and the Protection of the Lord 74 17 Lorenzo Snow Served God and His Fellowmen 77 18 Lorenzo Snow: Financing God’s Kingdom 84 19 Make Peer Pressure a Positive Experience 88 20 Joseph F. Smith—A Voice of Courage 93 21 Joseph F. Smith: Redemption of the Dead 98 22 Heber J. Grant—Man of Determination 105 23 Heber J. Grant: Success through Reliance on the Lord 110 24 Turning Weaknesses and Trials into Strengths 116 25 George Albert Smith: Responding to the Good 120 26 George Albert Smith: A Mission of Love 126 27 Peace in Troubled Times 132 iii 28 David O. -

EDUCATION in ZION We Move Forward Faithfully Into the Future Only by Understanding Our Past

EDUCATION IN ZION We move forward faithfully into the future only by understanding our past. Our founding stories reveal to us the higher purposes for which our forebears strove, and help us know the path that we should follow. Come unto me … and learn of me. —Matthew 11:28–29 I am the light, and the life, and the truth of the world. —Ether 4:12 I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit. —John 15:5 I am the good shepherd: the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep. —John 10:11 Feed my lambs. … Feed my sheep. —John 21:15–17 As Latter-day Saints, we believe Christ to be the Source of all light and truth, speaking through His prophets and enlightening and inspiring people everywhere. Therefore, we seek truth wherever it might be found and strive to shape our lives by it. In the Zion tradition, we share the truth freely so that every person might learn and grow and in turn strengthen others. From our faith in Christ and our love for one another, our commitment to education flows. Feed My Lambs, Feed My Sheep, by a BYU student, after a sculpture in the Vatican Library Hand-tufted wool rug, designed by a BYU student Circular skylight, Joseph F. Smith Building gallery [L] “Feed My Lambs … Feed My Sheep,” by a BYU student, after a sculpture in the Vatican Library [L] Hand-tufted wool rug, designed by a BYU student [L] Circular skylight, Joseph F. -

The Return of Oliver Cowdery

The Return of Oliver Cowdery Scott H. Faulring On Sunday, 12 November 1848, apostle Orson Hyde, president of the Quorum of the Twelve and the church’s presiding ofcial at Kanesville-Council Bluffs, stepped into the cool waters of Mosquito Creek1 near Council Bluffs, Iowa, and took Mormonism’s estranged Second Elder by the hand to rebaptize him. Sometime shortly after that, Elder Hyde laid hands on Oliver’s head, conrming him back into church membership and reordaining him an elder in the Melchizedek Priesthood.2 Cowdery’s rebaptism culminated six years of desire on his part and protracted efforts encouraged by the Mormon leadership to bring about his sought-after, eagerly anticipated reconciliation. Cowdery, renowned as one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon, corecipient of restored priesthood power, and a founding member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had spent ten and a half years outside the church after his April 1838 excommunication. Oliver Cowdery wanted reafliation with the church he helped organize. His penitent yearnings to reassociate with the Saints were evident from his personal letters and actions as early as 1842. Oliver understood the necessity of rebaptism. By subjecting himself to rebaptism by Elder Hyde, Cowdery acknowledged the priesthood keys and authority held by the First Presidency under Brigham Young and the Twelve. Oliver Cowdery’s tenure as Second Elder and Associate President ended abruptly when he decided not to appear and defend himself against misconduct charges at the 12 April -

Vol. 02 No. 1 Religious Educator

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 2 Number 1 Article 13 4-1-2001 Vol. 02 No. 1 Religious Educator Religious Educator Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Educator, Religious. "Vol. 02 No. 1 Religious Educator." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 2, no. 1 (2001). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol2/iss1/13 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RE COVER FALL 2001 10/17/01 10:26 AM Page 1 THE RELIGIOUS EDUCATOR • PERSPECTIVES ON • GOSPEL THE PERSPECTIVES RESTORED THE RELIGIOUS EDUCATOR Choosing the “Good Part” Jeremiah’s Imprisonment and INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Date of Lehi’s Departure The Sanctity of Food: A Latter-day Saint Perspective The Faith of a Prophet: BrighamYoung’s Life and Service—— VOL 2 NO 1 • 2001 A Pattern of Applied Faith Elder D. Todd Christofferson Jeremiah’s Imprisonment and the Date of Lehi’s Departure S. Kent Brown and David Rolph Seely The Faith The Sanctity of Food: A Mormon Perspective Paul H. Peterson of a Prophet: Choosing the “Good Part” Brent L. Top BrighamYoung’s Life and Service “He That Hath the Scriptures, Let Him Search Them” Elder D. Todd Christofferson Gaye Strathearn What Is Education? RELIGIOUS CENTER STUDIES • BRIGHAM UNIVERSITY YOUNG Matthew O. Richardson Reproving with Sharpness——When? Robert L. -

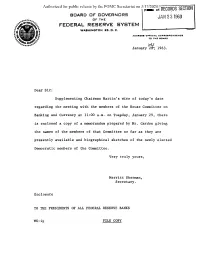

R in Records Section Jan2 3 1963

Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 3/17/2020 R INRECORDS SECTION BOARD OF GOVERNORS JAN2 3 1963 OF THE FEDERAL RESERVE SYST EM WASHINGTON 25. D. C. ADDRESS OFFICIAL CORRESPONDENCE TO THE BOARD January 1963. Dear Sir: Supplementing Chairman Martin's wire of today's date regarding the meeting with the members of the House Committee on Banking and Currency at 11:00 a.m. on Tuesday, January 29, there is enclosed a copy of a memorandum prepared by Mr. Cardon giving the names of the members of that Committee so far as they are presently available and biographical sketches of the newly elected Democratic members of the Committee. Very truly yours, Merritt Sherman, Secretary. Enclosure TO THE PRESIDENTS OF ALL FEDERAL RESERVE BANKS MS:ig FILE COPY Authorized for public release by the FOMC Secretariat on 3/17/2020RECD IN RECORDS SECTION JAN 25 1963 January 24, 1963 To Board of Governors Subject: Composition of the House From Robert L. Cardon Committee on Banking and Currency. The House today elected 13 Republican members of the Banking and Currency Committee, completing the roster as follows: Democrats Republicans Wright Patman, of Texas, Chairman Clarence E. Kilburn, of New York Albert Rains, of Alabama William B. Widnall, of New Jersey Abraham J. Multer, of New York Eugene Siler, of Kentucky William A. Barrett, of Pennsylvania Paul A. Fino, of New York Leonor Kretzer (Mrs. John B.) Florence P. Dwyer, of New Jersey Sullivan, of Missouri Seymour Halpern, of New York Henry S. Reuss, of Wisconsin James Harvey, of Michigan Thomas L.