Women in the Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legend of Romulus and Remus

THE LEGEND OF ROMULUS AND REMUS According to tradition, on April 21, 753 B.C., Romulus and his twin brother, Remus, found Rome on the site where they were suckled by a she-wolf as orphaned infants. Actually, the Romulus and Remus myth originated sometime in the fourth century B.C., and the exact date of Rome’s founding was set by the Roman scholar Marcus Terentius Varro in the first century B.C. According to the legend, Romulus and Remus were the sons of Rhea Silvia, the daughter of King Numitor of Alba Longa. Alba Longa was a mythical city located in the Alban Hills southeast of what would become Rome. Before the birth of the twins, Numitor was deposed by his younger brother Amulius, who forced Rhea to become a vestal virgin so that she would not give birth to rival claimants to his title. However, Rhea was impregnated by the war god Mars and gave birth to Romulus and Remus. Amulius ordered the infants drowned in the Tiber, but they survived and washed ashore at the foot of the Palatine hill, where they were suckled by a she-wolf until they were found by the shepherd Faustulus. Reared by Faustulus and his wife, the twins later became leaders of a band of young shepherd warriors. After learning their true identity, they attacked Alba Longa, killed the wicked Amulius, and restored their grandfather to the throne. The twins then decided to found a town on the site where they had been saved as infants. They soon became involved in a petty quarrel, however, and Remus was slain by his brother. -

Humanitas–Clementia and Clementia Caesaris Ancient and Modern Caesar

European Journal of Science and Theology, September 2012, Vol.8, No.3, 263-269 _______________________________________________________________________ HUMANITAS–CLEMENTIA AND CLEMENTIA CAESARIS ANCIENT AND MODERN CAESAR Iulian-Gabriel Hruşcă* Romanian Academy, Iasi Branch, Str. T. Codrescu, Nr. 2, Iasi, Romania (Received 11 May 2012) Abstract Humanitas Romana is a concept that crosses both the Republican age of Rome and the Roman imperial period. In the Republic, clementia was both a personal attribute and a public virtue, intended to differentiate the Romans from the other peoples of antiquity in a sense of a moral superiority. In the Roman imperial period, the concept of humanitas Romana began to manifest more and more significantly through its component part, clementia, which became a cardinal virtue of the emperor and a judicial principle. With the coming to power of Julius Caesar, the notion of Clementia Caesaris was born. Afterwards, the status of Clementia Caesaris was enhanced during the Principate of Augustus. The emperor tends to become a provider of human rights. In a certain respect, if we refer to the principles of democracy, this transfer of the centre of gravity to the emperor in terms of human rights is negative. However, we could not assert that at that time were only negative aspects. We might consider as positive aspects the evolution of the concept of humanitas Romana through its component, the virtue of clementia, or the increased multicultural side of the Roman state. Despite the negative perception of Rome today, the clemency of ancient Caesar had reminiscences over time. The modern Caesar has tried to turn to Rome for lessons both positive and negative. -

Livy's View of the Roman National Character

James Luce, December 5th, 1993 Livy's View of the Roman National Character As early as 1663, Francis Pope named his plantation, in what would later become Washington, DC, "Rome" and renamed Goose Creek "Tiber", a local hill "Capitolium", an example of the way in which the colonists would draw upon ancient Rome for names, architecture and ideas. The founding fathers often called America "the New Rome", a place where, as Charles Lee said to Patrick Henry, Roman republican ideals were being realized. The Roman historian Livy (Titus Livius, 59 BC-AD 17) lived at the juncture of the breakdown of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. His 142 book History of Rome from 753 to 9 BC (35 books now extant, the rest epitomes) was one of the most read Latin authors by early American colonists, partly because he wrote about the Roman national character and his unique view of how that character was formed. "National character" is no longer considered a valid term, nations may not really have specific national characters, but many think they do. The ancients believed states or peoples had a national character and that it arose one of 3 ways: 1) innate/racial: Aristotle believed that all non-Greeks were barbarous and suited to be slaves; Romans believed that Carthaginians were perfidious. 2) influence of geography/climate: e.g., that Northern tribes were vigorous but dumb 3) influence of institutions and national norms based on political and family life. The Greek historian Polybios believed that Roman institutions (e.g., division of government into senate, assemblies and magistrates, each with its own powers) made the Romans great, and the architects of the American constitution read this with especial care and interest. -

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

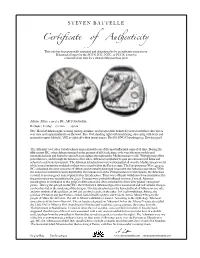

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Graham Jones

Ni{ i Vizantija XIV 629 Graham Jones SEEDS OF SANCTITY: CONSTANTINE’S CITY AND CIVIC HONOURING OF HIS MOTHER HELENA Of cities and citizens in the Byzantine world, Constantinople and its people stand preeminent. A recent remark that the latter ‘strove in everything to be worthy of the Mother of God, to Whom the city was dedicated by St Constantine the Great in 330’ follows a deeply embedded pious narrative in which state and church intertwine in the city’s foundation as well as its subse- quent fortunes. Sadly, it perpetuates a flawed reading of the emperor’s place in the political and religious landscape. For a more nuanced and considered view we have only to turn to Vasiliki Limberis’ masterly account of politico-religious civic transformation from the reign of Constantine to that of Justinian. In the concluding passage of Divine Heiress: The Virgin Mary and the Creation of Christianity, Limberis reaffirms that ‘Constantinople had no strong sectarian Christian tradition. Christianity was new to the city, and it was introduced at the behest of the emperor.’ Not only did the civic ceremonies of the imperial cult remain ‘an integral part of life in the city, breaking up the monotony of everyday existence’. Hecate, Athena, Demeter and Persephone, and Isis had also enjoyed strong presences in the city, some of their duties and functions merging into those of two protector deities, Tyche Constantinopolis, tutelary guardian of the city and its fortune, and Rhea, Mother of the Gods. These two continued to be ‘deeply ingrained in the religious cultural fabric of Byzantium.. -

Diana (Old Lady) Apollo (Old Man) Mars (Old Man)

Diana (old lady) Dia. (shuddering.) Ugh! How cold the nights are! I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel the night air a great deal more than I used to. But it is time for the sun to be rising. (Calls.) Apollo. Ap. (within.) Hollo! Dia. I've come off duty - it's time for you to be getting up. Enter APOLLO. He is an elderly 'buck' with an air of assumed juvenility, and is dressed in dressing gown and smoking cap. Ap. (yawning.) I shan't go out today. I was out yesterday and the day before and I want a little rest. I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel my work a great deal more than I used to. Dia. I'm sure these short days can't hurt you. Why, you don't rise till six and you're in bed again by five: you should have a turn at my work and just see how you like that - out all night! Apollo (Old man) Dia. (shuddering.) Ugh! How cold the nights are! I don't know how it is, but I seem to feel the night air a great deal more than I used to. But it is time for the sun to be rising. (Calls.) Apollo. Ap. (within.) Hollo! Dia. I've come off duty - it's time for you to be getting up. Enter APOLLO. He is an elderly 'buck' with an air of assumed juvenility, and is dressed in dressing gown and smoking cap. -

Let's Think About This Reasonably: the Conflict of Passion and Reason

Let’s Think About This Reasonably: The Conflict of Passion and Reason in Virgil’s The Aeneid Scott Kleinpeter Course: English 121 Honors Instructor: Joan Faust Essay Type: Poetry Analysis It has long been a philosophical debate as to which is more important in human nature: the ability to feel or the ability to reason. Both functions are integral in our composition as balanced beings, but throughout history, some cultures have invested more importance in one than the other. Ancient Rome, being heavily influenced by stoicism, is probably the earliest example of a society based fundamentally on reason. Its most esteemed leaders and statesmen such as Cicero and Marcus Aurelius are widely praised today for their acumen in affairs of state and personal ethics which has survived as part of the classical canon. But when mentioning the classical canon, and the argument that reason is essential to civilization, a reader need not look further than Virgil’s The Aeneid for a more relevant text. The Aeneid’s protagonist, Aeneas, is a pious man who relies on reason instead of passion to see him through adversities and whose actions are foiled by a cast of overly passionate characters. Personages such as Dido and Juno are both portrayed as emotionally-laden characters whose will is undermined by their more rational counterparts. Also, reason’s importance is expressed in a different way in Book VI when Aeneas’s father explains the role reason will play in the future Roman Empire. Because The Aeneid’s antagonists are capricious individuals who either die or never find contentment, the text very clearly shows the necessity of reason as a human trait for survival and as a means to discover lasting happiness. -

Intimations of Dido and Cleopatra in Some Contemporary Portrayals of Elizabeth I

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange Faculty Publications Classics Spring 1999 Intimations of Dido and Cleopatra in Some Contemporary Portrayals of Elizabeth I Clifford Weber Kenyon College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Weber, Clifford, "Intimations of Dido and Cleopatra in Some Contemporary Portrayals of Elizabeth I" (1999). Faculty Publications. Paper 10. https://digital.kenyon.edu/classics_pubs/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Intimations of Dido and Cleopatra in Some Contemporary Portrayals of Elizabeth I Author(s): Clifford Weber Source: Studies in Philology, Vol. 96, No. 2 (Spring, 1999), pp. 127-143 Published by: University of North Carolina Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4174634 . Accessed: 08/10/2014 15:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of North Carolina Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studies in Philology. -

Chapter Five: Cupid and Psyche

Chapter Five: Cupid and Psyche (from Mythology for Today Hamilton’s Mythology) 1. Venus becomes jealous because Psyche’s surpassing beauty has transfixed all the mortals, so that they forget Venus, and neglect her temples and altars. 2. Venus plans to have her son, Cupid, shoot Psyche with a love arrow, so that Psyche will fall in love with a hideous creature. Venus’ plan fails because Cupid himself falls in love with the beautiful Psyche. 3. Psyche’s father believes that he must leave her on the summit to be claimed by her serpent‐husband, for this is what he has been told by the Oracle of Apollo. However, the truth is that Cupid has arranged this himself, so that he can carry Psyche away as his own bride. 4. Her sisters become jealous of Psyche’s superior riches and treasures. 5. Psyche is torn between her love for and her faith in her husband, and the doubt and fear her sisters cause her to feel. She is unable to live with the uncertainty of not knowing the truth. 6. When Psyche sees that her husband is a beautiful youth, she feels too ashamed of her suspicion that she is about to plunge the knife intended for him into her own breast. However, her hand trembles and the knife falls. This faltering saves her own life, but also causes her to drip some lamp oil on Cupid, who sees that she has betrayed him and runs away. 7. Psyche is made to separate by kind a huge mixed mass of tiny grains; ants separate them for her. -

Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham's Minerva Britanna

Brief Chronicles IV (2012-13) 89 Triangular Numbers in Henry Peacham’s Minerva Britanna: A Study in Jacobean Literary Form Roger Stritmatter his article investigates the presence of a concealed and previously undetected numerical symbolism in a Stuart-era emblem book, Henry TPeacham’s Minerva Britanna (1611). Although alien to modern conceptions of art, emblem books constitute one of the most widely published and popular genres in early modern book production. Drawing from an eclectic tradition of literary, religious, and iconological traditions, the emblem book combined words and images into complex patterns of signification, often of a markedly didactic character. Popular in all the European vernaculars, it appealed to a wide range of Renaissance readers, from the nearly illiterate (by virtue of its illustrated nature) to the most erudite (by virtue of its reputation for dazzling displays of intellectual and aesthetic virtuosity). By convention the emblem was divided into three parts: superscriptio, pictura, and subscriptio: the superscriptio was the short legend or motto that typically appeared at the top of the page; below it appeared the pictura – the emblem per se – followed by the subscriptio, a longer responsive analysis, usually written in verse, which completed the design. While emblem book scholars still debate the exact relationship between the three parts – and no doubt individual emblem writers themselves sometimes conceived of it in different ways, Deitrich Walter Jöns’ definition constitutes a useful and standard point