On Cue 1 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brothers Wreck by Jada Alberts Director Leah Purcell Set & Costume Designer Dale Ferguson Lighting Designer Luiz Pampolha Composer & Sound Designer Brendan O’Brien

Media Release April 2014 Belvoir presents Brothers Wreck By Jada Alberts Director Leah Purcell Set & Costume Designer Dale Ferguson Lighting Designer Luiz Pampolha Composer & Sound Designer Brendan O’Brien With Cramer Cain Lisa Flanagan Rarriwuy Hick Hunter Page-Lochard Bjorn Stewart Belvoir St Theatre | Upstairs 24 May – 22 June 2014 ‘it shouldn’t be this hard... but look around ay? You're not the only one who's lost a brother this way.’ Brothers Wreck begins with a death: on a hot morning under a house in Darwin, Ruben wakes to find his cousin Joe hanging from the rafters. The play that follows tells the story of how Ruben’s family, little by little, brings Ruben back from the edge. It is a confronting and honest exploration of grief and loss but ultimately redemption. Jada Alberts, winner of the 2013 Balnaves Foundation Indigenous Playwright’s Award, is an actor and theatre-maker with a powerful voice and a clear vision to tell the stories of her community. She is one of a growing group of young Indigenous artists who have looked to each other as much as they have to their elders for inspiration. Her play emerges from the gathering voices of this new generation and tells a deeply relevant and current story of the reality of life for many Indigenous families. An outstanding cast of Indigenous artists has been assembled. Rarriwuy Hick is gaining attention for her television performances in Redfern Now and The Gods of Wheat Street (ABC1). She is also a compelling stage actor, as well as a dancer and choreographer with Bangarra Dance Theatre. -

Final-Brochure-2020.Pdf

Ngadlu tampinthi Kaurna We acknowledge the Kaurna miyurna yaitya yarta-mathanya people as the traditional custodians Wama Tarntanyaku. of the Adelaide Plains. Parnaku yailtya, parnaku tapa We recognise and respect their purruna, parnaku yarta ngadlu cultural heritage, beliefs and tampinthi. Yalaka Kaurna Miyurna relationship with the land. itu yailtya, tapa purruna, yarta kuma We acknowledge that they are puru martinthi, puru warri-apinthi, of continuing importance to the puru tangka martulayinthi. Ngadlu Kaurna people living today and tampinthi purkarna pukinangku, pay respects to Elders past, yalaka, tarrkarritya. present and future. 2 2 A MESSAGE FROM MITCHELL So, shall we have some fun together? New Australian works of great heart, wit and humanity. New international works of great Shall we lift the curtain, open the door, enter daring and dazzling originality from and with into worlds strange, familiar or new? diverse voices. Classics reinvented to connect history to the here and now. Shall we get set for some of the greatest times that we will ever have in a theatre? There’s a lot of comedy coming your way this year - some satirical, some black and some Sound good? Well, come on in. deeply twisted. Plus works that will break apart the very notions of what you think theatre is. But I’m thrilled to be joining State Theatre all of our works will engage your mind and heart Company South Australia as its new Artistic as fulsomely as your funny bones are tickled. Director. I’ve loved working for this company in the past and I have loved witnessing so many You will leave many of our shows this of the brilliant works it has produced. -

Screen Australia Annual Report 2011/12 Published by Screen Australia October 2012 ISSN 1837-2740 © Screen Australia 2012

Screen Australia Annual Report 2011/12 Published by Screen Australia October 2012 ISSN 1837-2740 © Screen Australia 2012 The text in this Annual Report is released subject to a Creative Commons BY licence (Licence). This means, in summary, that you may reproduce, transmit and distribute the text, provided that you do not do so for commercial purposes, and provided that you attribute the text as extracted from Screen Australia’s Annual Report 2011/12. You must not alter, transform or build upon the text in this Annual Report. Your rights under the Licence are in addition to any fair dealing rights which you have under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cwlth). For further terms of the Licence, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/au/. You are not licensed to reproduce, transmit or distribute any still photographs contained in this Annual Report without the prior written permission of Screen Australia. This Annual Report is available to download as a PDF from www.screenaustralia.gov.au Front cover image from The Sapphires. Screen Australia Annual Report 2011/12 Correction Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport Screen Australia Annual Report 2011/12 Producer Offset and Co-productions – page 74: Incorrect total (173) for Producer Offset Provisional Certificates issued in 2011/12. It should read: 145 Provisional Certificates. Producer Offset and Co-productions – page 76: Under heading Certificates issued in 2011/12, the figures for Producer Offset Provisional Certificates (Features – 78; Non-feature documentaries – 54; TV and other – 41; Total – 173) are incorrect. The table should read: Certificates issued in 2011/12 Final Provisional Number Offset value ($m) Features 47 24 127.29 Non-feature documentaries 55 98 18.21 TV and other 43 39 58.45 Total 145 161 203.96 Note: Figures may not total exactly due to rounding. -

The Premiere Fund Slate for MIFF 2021 Comprises the Following

The MIFF Premiere Fund provides minority co-financing to new Australian quality narrative-drama and documentary feature films that then premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). Seeking out Stories That Need Telling, the the Premiere Fund deepens MIFF’s relationship with filmmaking talent and builds a pipeline of quality Australian content for MIFF. Launched at MIFF 2007, the Premiere Fund has committed to more than 70 projects. Under the charge of MIFF Chair Claire Dobbin, the Premiere Fund Executive Producer is Mark Woods, former CEO of Screen Ireland and Ausfilm and Showtime Australia Head of Content Investment & International Acquisitions. Woods has co-invested in and Executive Produced many quality films, including Rabbit Proof Fence, Japanese Story, Somersault, Breakfast on Pluto, Cannes Palme d’Or winner Wind that Shakes the Barley, and Oscar-winning Six Shooter. ➢ The Premiere Fund slate for MIFF 2021 comprises the following: • ABLAZE: A meditation on family, culture and memory, indigenous Melbourne opera singer Tiriki Onus investigates whether a 70- year old silent film was in fact made by his grandfather – civil rights leader Bill Onus. From director Alex Morgan (Hunt Angels) and producer Tom Zubrycki (Exile in Sarajevo). (Distributor: Umbrella) • ANONYMOUS CLUB: An intimate – often first-person – exploration of the successful, yet shy and introverted, 33-year-old queer Australian musician Courtney Barnett. From producers Pip Campey (Bastardy), Samantha Dinning (No Time For Quiet) & director Danny Cohen. (Dist: Film Art Media) • CHEF ANTONIO’S RECIPES FOR REVOLUTION: Continuing their series of food-related social-issue feature documentaries, director Trevor Graham (Make Hummus Not War) and producer Lisa Wang (Monsieur Mayonnaise) find a very inclusive Italian restaurant/hotel run predominately by young disabled people. -

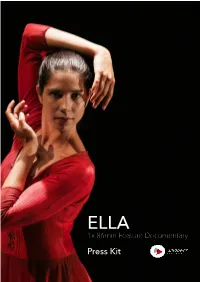

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

Hot Topics Indigenous Dvds May 2015

Hot topics Indigenous DVDs This guide contains descriptions of DVDs released Redfern now: the complete series since 2013 and an alphabetical listing of older releases. directed by Catriona McKenzie … et al. 761 min. Australian Broadcasting Anzacs: remembering our heroes. Corporation, 2015. DVD RED 11 x 15 min. SBS, 2015. DVD ANZ “Celebrated by audiences and critics alike, A series of 11 15-minute documentaries over two series and one telemovie, the produced by NITV which acknowledges the multiple award-winning Redfern now contributions of Indigenous people to explores powerful stories of contemporary Australia’s military efforts from the time of inner-city Indigenous life.” – Back cover. the Boer War to the present day. Classification : MA (Strong sexual violence and themes) Classification : PG (Mild themes) The Library also holds copies of both series 1 and series 2 as The Central Park five directed by Ken standalone DVDs. Burns, David McMahon and Sarah Burns. 112 min. Sydney: SBS1, 2013. Utopia: an epic story of struggle and DVD THE resistance by John Pilger. 110 min. + extras. Antidote Films, 2013. DVD UTO This film “tells the story of the five black and Latino teenagers from Harlem who were “Utopia is a vast region in northern Australia wrongly convicted of raping a white woman and home to the oldest human presence on in New York City’s Central Park in 1989. earth. ‘This film is a journey into that secret The film chronicles The Central Park country,’ says John Pilger, ‘It will describe Jogger case, for the first time from the perspective of these five not only the uniqueness of the first teenagers whose lives were upended by this miscarriage of Australians, but their trail of tears and justice.” – PBS website. -

DEADLYS® FINALISTS ANNOUNCED – VOTING OPENS 18 July 2013 Embargoed 11Am, 18.7.2013

THE NATIONAL ABORIGINAL & TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER MUSIC, SPORT, ENTERTAINMENT & COMMUNITY AWARDS DEADLYS® FINALISTS ANNOUNCED – VOTING OPENS 18 July 2013 Embargoed 11am, 18.7.2013 BC TV’s gripping, award-winning drama Redfern in the NBA finals, Patrick Mills, are finalists in the Male Sportsperson Now is a multiple finalist across the acting and of the Year category, joining two-time world champion boxer Daniel television categories in the 2013 Deadly Awards, Geale, rugby union’s Kurtley Beale and soccer’s Jade North. with award-winning director Ivan Sen’s Mystery Across the arts, Australia’s best Indigenous dancers, artists and ARoad and Satellite Boy starring the iconic David Gulpilil. writers are well represented. Ali Cobby Eckermann, the SA writer These were some of the big names in television and film who brought us the beautiful story Ruby Moonlight in poetry, announced at the launch of the 2013 Deadlys® today, at SBS is a finalist with her haunting memoir Too Afraid to Cry, which headquarters in Sydney, joining plenty of talent, achievement tells her story as a Stolen Generations’ survivor. Pioneering and contribution across all the award categories. Indigenous award-winning writer Bruce Pascoe is also a finalist with his inspiring story for lower primary-school readers, Fog Male Artist of the Year, which recognises the achievement of a Dox – a story about courage, acceptance and respect. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander musicians, will be a difficult category for voters to decide on given Archie Roach, Dan Sultan, The Deadly Award categories of Health, Education, Employment, Troy Cassar-Daley, Gurrumul and Frank Yamma are nominated. -

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania It Is 1968, Rural Western Austra

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania Abstract: In two Australian coming-of-age feature films, Australian Rules and September, the central young characters hold idyllic notions about friendship and equality that prove to be the keys to transformative on- screen behaviours. Intimate intersubjectivity, deployed in the close relationships between the indigenous and nonindigenous protagonists, generates multiple questions about the value of normalised adult interculturalism. I suggest that the most pointed significance of these films lies in the compromises that the young adults make. As they reach the inevitable moral crisis that awaits them on the cusp of adulthood, despite pressures to abandon their childhood friendships they instead sustain their utopian (golden) visions of the future. It is 1968, rural Western Australia. As we glide along an undulating bitumen road up ahead we see, from a low camera angle, a school bus moving smoothly along the same route. Periodically a smattering of roadside trees filters the sunlight, but for the most part open fields of wheat flank the roadsides and stretch out to the horizon, presenting a grand and golden vista. As we reach the bus, music that has hitherto been a quiet accompaniment swells and in the next moment we are inside the vehicle with a fair-haired teenager. The handsome lad, dressed in a yellow school uniform, is drawing a picture of a boxer in a sketchpad. Another cut takes us back outside again, to an equally magnificent view from the front of the bus. This mesmerising piece of cinema—the opening of September (Peter Carstairs, 2007)— affords a viewer an experience of tranquillity and promise, and is homage to the notion of a golden age of youth. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

2018 Brochure Web.Pdf

SEASON 2018 2 A message from Kip Williams 5 The top benefits of a Season Ticket 10 Insight Events 13 Get the most out of your Season Ticket THE PLAYS 16 Top Girls 18 Lethal Indifference 20 Black is the New White 22 The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui 24 Going Down 26 The Children 28 Still Point Turning: The Catherine McGregor Story 30 Blackie Blackie Brown 32 Saint Joan 34 The Long Forgotten Dream 36 The Harp in the South: Part One and Part Two 40 Accidental Death of an Anarchist 42 A Cheery Soul SPECIAL OFFERS 46 Hamlet: Prince of Skidmark 48 The Wharf Revue 2018 HOW TO BOOK AND USEFUL INFO 52 Let us help you choose 55 How to book your Season Ticket 56 Ticket prices 58 Venues and access 59 Dates for your diary 60 Walsh Bay Kitchen 61 The Theatre Bar at the End of the Wharf 62 The Wharf Renewal Project 63 Support us 64 Thank you 66 Our community 67 Partners 68 Contact details 1 A MESSAGE FROM KIP WILLIAMS STC is a company that means a lot to me. And, finally, I’ve thought about what theatre means to me, and how best I can share with It’s the company where, as a young teen, I was you the great passion and love I have for this inspired by my first experience of professional art form. It’s at the theatre where I’ve had some theatre. It’s the company that gave me my very of the most transformative experiences of my first job out of drama school. -

Company B ANNUAL REPORT 2008

company b ANNUAL REPORT 2008 A contents Company B SToRy ............................................ 2 Key peRFoRmanCe inDiCaToRS ...................... 30 CoRe ValueS, pRinCipleS & miSSion ............... 3 FinanCial Report ......................................... 32 ChaiR’S Report ............................................... 4 DiReCToRS’ Report ................................... 32 ArtistiC DiReCToR’S Report ........................... 6 DiReCToRS’ DeClaRaTion ........................... 34 GeneRal manaGeR’S Report .......................... 8 inCome STaTemenT .................................... 35 Company B STaFF ........................................... 10 BalanCe SheeT .......................................... 36 SeaSon 2008 .................................................. 11 CaSh Flow STaTemenT .............................. 37 TouRinG ........................................................ 20 STaTemenT oF ChanGeS in equiTy ............ 37 B ShaRp ......................................................... 22 noTeS To The FinanCial STaTements ....... 38 eDuCaTion ..................................................... 24 inDepenDenT auDiT DeClaRaTion CReaTiVe & aRTiSTiC DeVelopmenT ............... 26 & Report ...................................................... 49 CommuniTy AcceSS & awards ...................... 27 DonoRS, partneRS & GoVeRnmenT SupporteRS ............................ 28 1 the company b story Company B sprang into being out of the unique action taken to save Landmark productions like Cloudstreet, The Judas