Resilience and Christian Virtues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minding the Body Interacting Socially Through Embodied Action

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1112 Minding the Body Interacting socially through embodied action by Jessica Lindblom Department of Computer and Information Science Linköpings universitet SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2007 © Jessica Lindblom 2007 Cover designed by Christine Olsson ISBN 978-91-85831-48-7 ISSN 0345-7524 Printed by UniTryck, Linköping 2007 Abstract This dissertation clarifies the role and relevance of the body in social interaction and cognition from an embodied cognitive science perspective. Theories of embodied cognition have during the past two decades offered a radical shift in explanations of the human mind, from traditional computationalism which considers cognition in terms of internal symbolic representations and computational processes, to emphasizing the way cognition is shaped by the body and its sensorimotor interaction with the surrounding social and material world. This thesis develops a framework for the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition, which is based on an interdisciplinary approach that ranges historically in time and across different disciplines. It includes work in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, phenomenology, ethology, developmental psychology, neuroscience, social psychology, linguistics, communication, and gesture studies. The theoretical framework presents a thorough and integrated understanding that supports and explains the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition. It is argued that embodiment is the part and parcel of social interaction and cognition in the most general and specific ways, in which dynamically embodied actions themselves have meaning and agency. The framework is illustrated by empirical work that provides some detailed observational fieldwork on embodied actions captured in three different episodes of spontaneous social interaction in situ. -

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

Enable Electric in King George Cont

SUNDAY, 30 JULY, 2017 The King George took on an entirely different shape as the ENABLE ELECTRIC heavy rain fell on already-deadened ground. Despite the Epsom Oaks being staged in a thunderstorm, the latest Juddmonte IN KING GEORGE sensation had it slick there as she readily turned back Rhododendron (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) on June 2 and it was even quicker as she completed the double in the Irish equivalent two weeks prior to this. Tactics were certain to play a significant part here, with her potentially tricky draw in seven leaving her vulnerable to early scrimmaging, but Frankie was happy to let her bounce out and put her head in front until Maverick Wave crossed over to provide the lead. With Highland Reel (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}) for company as they ignored the pacemaker, Enable settled perfectly and had stablemate Jack Hobbs (GB) (Halling) behind along with Idaho as Ulysses travelled with his customary ease and Jim Crowley tracked their every move. Before the turn for home Highland Reel was the first to struggle, and as he laboured and Ulysses nipped up his inner Enable dominates a rain-soaked King George | Racing Post Idaho lost vital momentum, but Enable moved forward with Jack Hobbs and for a brief period a Gosden one-two was likely. It is rare that the mud flies in the G1 King George VI and Whereas the pink-and-green surged on, the royal blue began to Queen Elizabeth S., a AWin And You=re In@ for the GI Breeders= drop away and it was Ulysses who was left to chase the runaway Cup Turf at Del Mar in November, but Khalid Abdullah=s Enable filly. -

Viktor Frankl Institut Online Bibliographie: Zeitschriftenartikel

VIKTOR FRANKL INSTITUT ONLINE BIBLIOGRAPHIE: ZEITSCHRIFTENARTIKEL A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A → Abadjieff, Esperanza María: "El amor en la pareja: posibilidad de una familia saludable", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XII, Nr.22, Mayo 1996, p. 37 Abinya, Irina: Celebrating the Meaning of the Moment through Photography: An Experiential Report. The International Forum for Logotherapy, Volume 38, Number 2, Autumn 2015, p. 69 Aboumrad, Elma Arozqueta: La plenitud del instante. Revista Mexicana de Logoterapia, Numero 23 / Primavera 2010, p. 66 Abrami, Leo Michael: The healing power of humor in logotherapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, Volume 32, Number 1, Spring 2009, p. 7 Abrami, Leo Michael: Vocation and Freedom. The International Forum for Logotherapy, Volume 35, Number 2, Autumn 2012, p. 80 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Reseña de libros: «Logoterapia: una alternativa ante la frustración existencial y las adicciones» de Efren Martínez Ortíz", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XV, Nr.28, Mayo 1999, p. 48 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "La búsqueda de sentido y su efecto terapéutico", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XV, Nr.28, Mayo 1999, p. 4 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Acto recordatorio con motivo de la muerte de Viktor Frankl", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XIII, Nr.25, Noviembre 1997, p. 8 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "El sentido y sus implicancias terapéuticas", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XI, Nr.20, Mayo 1995, p.22 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Drogadependencia desde la visión antropológica", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año IX, Nr.16, Abril 1993, p.22 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Comentario acerca del VI° Congreso Argentino I Encuentro Puntano de Logoterapia", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año VII, Nr.13, Noviembre 1991, p. -

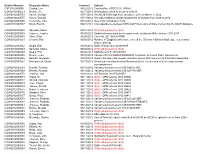

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2012000005 Guidos, Lori 06/22/2012 Contract No

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2012000005 Guidos, Lori 06/22/2012 Contract No. HSSCCG11J00088 COW2012000553 Melton, K.E. 05/31/2012 Information related to Vacancy 624276 COW2012000554 Vance, Donald 05/31/2012 All USCIS FOIA logs from January 1, 2011 to March 1, 2012 COW2012000555 Vance, Donald 05/31/2012 Records relating to all USCIS payment to Verizon from 2009 to 2010 COW2012000556 Ciccarone, Lilin 05/16/2012 New York Immigration Fund COW2012000557 Mock, Brentin 06/01/2012 Correspondence between DHS and Fl Secretary of State concerning the SAVE database COW2012000558 Zamudio, Maria 06/01/2012 Withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2012000559 Holmes, Jennifer 06/05/2012 Statistical Information on decsions made by Asylum Officers from 1991-2011 COW2012000560 Viker, Elliot 06/05/2012 Case No. 201106424 PRMI COW2012000561 Choucri, Mai 06/06/2012 Number of Egyptians who have entered the US from 1990 to include age, sex, marital status, and city COW2012000562 Siegal, Erin 06/06/2012 DOS referral Case 201001905 COW2012000563 Zamudio, Maria 06/06/2012 Withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2012000564 Siegal, Erin 06/06/2012 DOS Referral F-2010-00014 COW2012000565 Newell, Jean 06/07/2012 Vacancy ID CIS-596922-FDNS/NSC to include Selection Panel Documents COW2012000566 Estrella, Alejandro 06/07/2012 Inquiry into how many people and their names that requester is financially supporting COW2012000567 Montgomery, David 06/10/2012 All documents submitted by Manassas Ballet Theater and related congressional correspondence COW2012000568 Debrito, Ricardo -

UNIVERSIDADE DE SOROCABA PRÓ-REITORIA ACADÊMICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO Elaine Marasca Garcia Da Costa

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE SOROCABA PRÓ-REITORIA ACADÊMICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO Elaine Marasca Garcia da Costa SAÚDE NA EDUCAÇÃO: INDÍCIOS DE CONGRUÊNCIAS ENTRE SALUTOGÊNESE E PEDAGOGIA WALDORF Sorocaba/SP 2017 2 Elaine Marasca Garcia da Costa SAÚDE NA EDUCAÇÃO: INDÍCIOS DE CONGRUÊNCIAS ENTRE SALUTOGÊNESE E PEDAGOGIA WALDORF Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade de Sorocaba, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Educação. Orientadora: Profª Drª Vilma Lení Nista- Piccolo. Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Jonas Bach Jr. Sorocaba/SP 2017 3 Ficha Catalográfica Costa, Elaine Marasca Garcia. C871s Saúde na educação : indícios de congruências entre Salutogêne- se e Pedagogia Waldorf / Elaine Marasca Garcia da Costa. -- Sorocaba, 2017. 307f. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Vilma Lení Nista-Piccolo. Co-orientador: Prof. Dr.Jonas Bach Jr. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de Sorocaba, Sorocaba, SP, 2017. 1. Educação para a saúde. 2. Waldorf - Método de educação. Salutogênese. I. Nista-Piccolo, Vilma Lení, orient. II. Bach Jr., Jonas, co-orient. III. Título. IV. Indícios de congruências entre Salutogênese e Pedagogia Waldorf. V. Universidade de Sorocaba. 4 5 A Yolanda, minha mãe; Benedita, minha avó; Catarina e Maria Lúcia, minhas professoras. 6 AGRADECIMENTOS A todos que, direta ou indiretamente, participaram desse trabalho, física, anímica ou espiritualmente. Esta pesquisa também é fruto de cooperação científica entre a Universidade de Sorocaba e a Alice Salomon Hochschule Berlin – Alemanha. 7 Quando a natureza sadia do homem atua como um todo; quando ele se sente no mundo como um todo grande, belo, digno e valioso; quando o bem estar harmonioso lhe proporciona um encantamento livre, então o próprio Universo, se pudesse sentir a si mesmo, alegrar-se-ia como se tivesse cumprido sua missão, admirando o auge de sua evolução e de sua essência (GOETHE). -

Conference Papers

CONFERENCE PAPERS Annual Conference of the National Association of Jewish Center Workers June 8-12,1968 Detroit, Michigan NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH CENTER WORKERS 15 East 26th Street • New York, N.Y. I 001 0 י י G> iA .3 ~ ע H£ A//UaiCMN JEWISH COMMITTEE־1 Biaustein Library {׳"־ PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE AH of us who had-the privilege of taking part in the 1968 , י -V ' ' NAJCW Conference in Oetroit are exceedingly grateful to I Mi 11iam Kahn and Rose Movitch, Chairman and Co-Chairman respec- tively pf the Conference Program Committee. They and their co-workers developed a program which was most relevant to the times and, therefore, to the theme of the Conference, "Society in Crisis: The Response of the Jewish Community." The papers contained in this volume were presented at the plenary meetings and at the institute and workshop Sessions. We express our deep appreciation; to the writers of the papers, as well as to Herman 1. Sainer •for guiding the preparation of this volume. A particular word of appreciation is due to Mrs, Ethel Greenwaid for her skillful and dedicated service as office secretary for NAjCW. The cooperation of Mrs. Pearl Goldstein, and of the production staff of JWB is also noted with deep appreciation. The publication of this edition of the Conference Papers per- petuates the Idea conceived by Louis Kraft, Honorary President of NAJCW, that it is of great value to the Jewish Community Center field to preserve the product of NAJCW's Annual Conferences through such an annual volume. HERBERT MlLLMAN President INTRODUCTION It was a good feeling once aga(^: seeing old and new colleagues and having the opportunity to share experiences of the past year. -

![Newgate Stud Co & Anor V Penfold & Anor [2004] EWHC 2993](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6189/newgate-stud-co-anor-v-penfold-anor-2004-ewhc-2993-1446189.webp)

Newgate Stud Co & Anor V Penfold & Anor [2004] EWHC 2993

Newgate Stud Co & Anor v Penfold & Anor [2004] EWHC 2993 (Ch) (21 December 2004) Source: http://www.bailii.org Cite as: [2004] EWHC 2993 (Ch) Neutral Citation Number: [2004] EWHC 2993 (Ch) Case No: HC03C02972 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE CHANCERY DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL 21/12/2004 B e f o r e : THE HONOURABLE MR JUSTICE DAVID RICHARDS ____________________ Between: (1) Newgate Stud Company (2) Newgate Stud Farm LLC Claimants - and - (1) Anthony Penfold (2) Penfold Bloodstock Limited Defendants ____________________ Anthony Trace QC and Edmund Cullen (instructed by Baker & McKenzie) for the Claimants Jeremy Stuart-Smith QC and Graeme McPherson (instructed by Charles Russell) for the Defendants Hearing dates: 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 27 and 29 July 2004 ____________________ HTML VERSION OF JUDGMENT ____________________ Crown Copyright © Mr Justice David Richards : 1. HRH Prince Fahd bin Salman al Saud was a prominent figure in the racing and bloodstock world. In the 1980s and 1990s he was acknowledged as one of the leading owners and breeders of high-class thoroughbred horses, achieving a number of notable successes. Prince Fahd was the nephew of King Fahd of Saudi Arabia. His father was governor of Riyadh and he himself held high office in Saudi Arabia. 2. The racing and bloodstock interests of Prince Fahd were organised in Europe through Newgate Stud Company (Newgate UK), an unlimited company formed in 1983 under the Companies Act 1948 to 1981. Newgate Stud Farm Inc was formed in 1985 in Kentucky to conduct his racing and bloodstock activities in the United States. -

2020 Stallions Brochure

THE AGA KHAN STUDS Success Breeds Success 2020 60 Years of Breeding and Success Horses in pre-training at Gilltown Stud CONTENTS Breeders’ Letter 5 Dariyan 8 Harzand 20 Sea The Stars 32 Siyouni 44 Zarak 56 Success Breeds Success 68 60 Years of Breeding and Racing 72 Group One Winners 79 Contacts 80 Dourdana on the left and Darinja with her colt foal by Pivotal Soriya and her filly foal by Golden Horn 4 Dear Breeders, 2020 marks the 60th anniversary of His Highness the Aga Khan taking responsibility for the family thoroughbred enterprise. This breeding and racing activity have evolved and progressed over the decades and the Aga Khan Studs now boast high-class commercial stallions, prestigious maternal lines, and successful racehorses that have gathered more than 150 Group 1 victories. The Aga Khan Studs flagship sires, Sea The Stars and Siyouni, are members of the elite ranks of European stallions and both enjoyed further Classic glory in 2019. Gilltown Stud’s Sea The Stars won a second consecutive Irish Oaks thanks to the exceptional Star Catcher, also winner of the Prix Vermeille and British Champions Fillies & Mares Stakes, while Crystal Ocean shared Longines World’s Best Racehorse honours with Enable and Waldgeist, and champion stayer Stradivarius recorded a streak of ten consecutive races. Haras de Bonneval resident Siyouni was again crowned leading French-based sire. His principal representative was Pat Downes Prix du Jockey Club hero and Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe third Sottsass, and 2018 Prix de Diane winner Laurens brought her Manager, Irish Studs Group 1 score up to six with victory in the Prix Rothschild during August. -

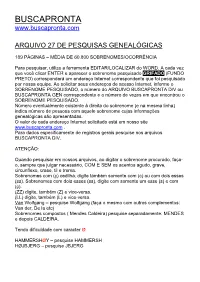

Adams Adkinson Aeschlimann Aisslinger Akkermann

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 27 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 189 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 60.800 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expression Quadrennial Periodic Report 2016-2019 - United Arab Emirates

2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expression Quadrennial Periodic Report 2016-2019 - United Arab Emirates General Information Describe the multi-stakeholder consultation process established for the preparation of this report, including consultations with relevant ministries, public institutions, local governments and civil society organizations Official letters were sent to 103 stakeholders including federal and local governments, private and public institutions and civil society organizations, inviting them to appoint a focal point within their organizations who can work with the UAE National Commission to prepare the UAE’s QPR for the period 2016-2019. One-on-one meetings were held with each stakeholder to discuss the objectives of the report and address any questions regarding the report. All stakeholders provided their input to the report in writing. In many cases, multiple follow up phone calls and meetings were held with stakeholders to further refine the responses. Further, the National Commission team conducted extensive desk research to find examples of good practices. The responses from stakeholders were studied, and together with the results of the desk research served to shape the report as seen below. The UAE National Commission has had to edit, paraphrase, summarize, and supplement some information submitted by partners to ensure a holistic narrative, accuracy, readability, and suitability for the purposes of this report. Furthermore, it must be noted that the information provided in the report is a reflection of the data available at the time of writing and that, in some cases, what is included in this report may be adapted, refocused or amended. -

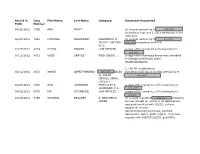

Recv'd in FOIA Case Number First Name Last Name Company Document Requested 04/25/2012 7359 ANN PRATT All Records Pertaining to I

Recv'd in Case First Name Last Name Company Document Requested FOIA Number 04/25/2012 7359 ANN PRATT all records pertaining to (b)6, (b)7c including a copy any I-130’s pertaining to the individual 04/25/2012 7454 CRISTINA MONTERREY MONTERREY & all records pertaining to (b)6, (b)7c TELLEZ LAW FIRM (b)6, (b)7c encounters with ICE PLLC 04/25/2012 8429 ALEXIS TORRES LAW OFFICES a copy of the complete a-file belonging to (b)6, (b)7c 04/12/2012 8472 ROSE SANTOS FOIA GROUP, . a copy of the following documents identified to HSHQDC06D00026 Order HSCETC09J00035 1.) All TO modifications 04/12/2012 8473 JORGE LOPEZ-MORENO (b)6, (b)7c GILES everything ICE has in its files pertaining to W. DALBY (b)6, (b)7c CORRECTIONAL FACILITY 04/25/2012 8926 MEG JACOBSON PRITCHETT & a copy of the complete a-file belonging to JACOBSON, P.S. (b)6, (b)7c 04/25/2012 9570 KIP STEINBERG LAW OFFICES a copy of the complete a-file belonging to (b)6, (b)7c 04/25/2012 9766 RICHARD BRACKEN R. BRACKEN & all records regarding (b)6, (b)7c including ASSOC but not limited to: copies of all applications and petitions filed with USCIS, notices, departure records, decisions/denials/approvals, parolled documents, OSC’s, EOIR records, interview records with INS/ICE/USCIS, and RFE’s 04/02/2012 10277 CHRISTINE HASS NBC 7 SAN DIEGO current policy regarding sex hormones for transgendered detainees in ICE custody. The names of the sex hormone medications provided for transgendered detainees and the quantity issued to these detainees from the time period of Jan 2010 to present.