Conference Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

Viktor Frankl Institut Online Bibliographie: Zeitschriftenartikel

VIKTOR FRANKL INSTITUT ONLINE BIBLIOGRAPHIE: ZEITSCHRIFTENARTIKEL A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z A → Abadjieff, Esperanza María: "El amor en la pareja: posibilidad de una familia saludable", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XII, Nr.22, Mayo 1996, p. 37 Abinya, Irina: Celebrating the Meaning of the Moment through Photography: An Experiential Report. The International Forum for Logotherapy, Volume 38, Number 2, Autumn 2015, p. 69 Aboumrad, Elma Arozqueta: La plenitud del instante. Revista Mexicana de Logoterapia, Numero 23 / Primavera 2010, p. 66 Abrami, Leo Michael: The healing power of humor in logotherapy. The International Forum for Logotherapy, Volume 32, Number 1, Spring 2009, p. 7 Abrami, Leo Michael: Vocation and Freedom. The International Forum for Logotherapy, Volume 35, Number 2, Autumn 2012, p. 80 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Reseña de libros: «Logoterapia: una alternativa ante la frustración existencial y las adicciones» de Efren Martínez Ortíz", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XV, Nr.28, Mayo 1999, p. 48 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "La búsqueda de sentido y su efecto terapéutico", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XV, Nr.28, Mayo 1999, p. 4 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Acto recordatorio con motivo de la muerte de Viktor Frankl", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XIII, Nr.25, Noviembre 1997, p. 8 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "El sentido y sus implicancias terapéuticas", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año XI, Nr.20, Mayo 1995, p.22 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Drogadependencia desde la visión antropológica", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año IX, Nr.16, Abril 1993, p.22 Acevedo, Gerónimo A.: "Comentario acerca del VI° Congreso Argentino I Encuentro Puntano de Logoterapia", Revista: "LOGO: teoría, terapia, actitud", Buenos Aires, Año VII, Nr.13, Noviembre 1991, p. -

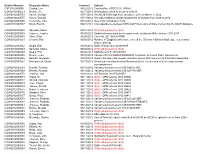

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2012000005 Guidos, Lori 06/22/2012 Contract No

Control Number Requester Name Scanned Subject CNT2012000005 Guidos, Lori 06/22/2012 Contract No. HSSCCG11J00088 COW2012000553 Melton, K.E. 05/31/2012 Information related to Vacancy 624276 COW2012000554 Vance, Donald 05/31/2012 All USCIS FOIA logs from January 1, 2011 to March 1, 2012 COW2012000555 Vance, Donald 05/31/2012 Records relating to all USCIS payment to Verizon from 2009 to 2010 COW2012000556 Ciccarone, Lilin 05/16/2012 New York Immigration Fund COW2012000557 Mock, Brentin 06/01/2012 Correspondence between DHS and Fl Secretary of State concerning the SAVE database COW2012000558 Zamudio, Maria 06/01/2012 Withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2012000559 Holmes, Jennifer 06/05/2012 Statistical Information on decsions made by Asylum Officers from 1991-2011 COW2012000560 Viker, Elliot 06/05/2012 Case No. 201106424 PRMI COW2012000561 Choucri, Mai 06/06/2012 Number of Egyptians who have entered the US from 1990 to include age, sex, marital status, and city COW2012000562 Siegal, Erin 06/06/2012 DOS referral Case 201001905 COW2012000563 Zamudio, Maria 06/06/2012 Withheld pursuant to (b)(6) COW2012000564 Siegal, Erin 06/06/2012 DOS Referral F-2010-00014 COW2012000565 Newell, Jean 06/07/2012 Vacancy ID CIS-596922-FDNS/NSC to include Selection Panel Documents COW2012000566 Estrella, Alejandro 06/07/2012 Inquiry into how many people and their names that requester is financially supporting COW2012000567 Montgomery, David 06/10/2012 All documents submitted by Manassas Ballet Theater and related congressional correspondence COW2012000568 Debrito, Ricardo -

UNIVERSIDADE DE SOROCABA PRÓ-REITORIA ACADÊMICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO Elaine Marasca Garcia Da Costa

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE SOROCABA PRÓ-REITORIA ACADÊMICA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO Elaine Marasca Garcia da Costa SAÚDE NA EDUCAÇÃO: INDÍCIOS DE CONGRUÊNCIAS ENTRE SALUTOGÊNESE E PEDAGOGIA WALDORF Sorocaba/SP 2017 2 Elaine Marasca Garcia da Costa SAÚDE NA EDUCAÇÃO: INDÍCIOS DE CONGRUÊNCIAS ENTRE SALUTOGÊNESE E PEDAGOGIA WALDORF Tese apresentada à Banca Examinadora do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade de Sorocaba, como exigência parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Educação. Orientadora: Profª Drª Vilma Lení Nista- Piccolo. Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Jonas Bach Jr. Sorocaba/SP 2017 3 Ficha Catalográfica Costa, Elaine Marasca Garcia. C871s Saúde na educação : indícios de congruências entre Salutogêne- se e Pedagogia Waldorf / Elaine Marasca Garcia da Costa. -- Sorocaba, 2017. 307f. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Vilma Lení Nista-Piccolo. Co-orientador: Prof. Dr.Jonas Bach Jr. Tese (Doutorado em Educação) - Universidade de Sorocaba, Sorocaba, SP, 2017. 1. Educação para a saúde. 2. Waldorf - Método de educação. Salutogênese. I. Nista-Piccolo, Vilma Lení, orient. II. Bach Jr., Jonas, co-orient. III. Título. IV. Indícios de congruências entre Salutogênese e Pedagogia Waldorf. V. Universidade de Sorocaba. 4 5 A Yolanda, minha mãe; Benedita, minha avó; Catarina e Maria Lúcia, minhas professoras. 6 AGRADECIMENTOS A todos que, direta ou indiretamente, participaram desse trabalho, física, anímica ou espiritualmente. Esta pesquisa também é fruto de cooperação científica entre a Universidade de Sorocaba e a Alice Salomon Hochschule Berlin – Alemanha. 7 Quando a natureza sadia do homem atua como um todo; quando ele se sente no mundo como um todo grande, belo, digno e valioso; quando o bem estar harmonioso lhe proporciona um encantamento livre, então o próprio Universo, se pudesse sentir a si mesmo, alegrar-se-ia como se tivesse cumprido sua missão, admirando o auge de sua evolução e de sua essência (GOETHE). -

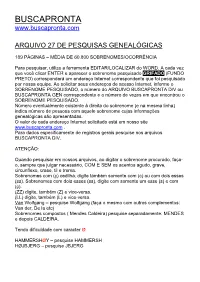

Adams Adkinson Aeschlimann Aisslinger Akkermann

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 27 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 189 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 60.800 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

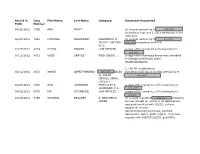

Recv'd in FOIA Case Number First Name Last Name Company Document Requested 04/25/2012 7359 ANN PRATT All Records Pertaining to I

Recv'd in Case First Name Last Name Company Document Requested FOIA Number 04/25/2012 7359 ANN PRATT all records pertaining to (b)6, (b)7c including a copy any I-130’s pertaining to the individual 04/25/2012 7454 CRISTINA MONTERREY MONTERREY & all records pertaining to (b)6, (b)7c TELLEZ LAW FIRM (b)6, (b)7c encounters with ICE PLLC 04/25/2012 8429 ALEXIS TORRES LAW OFFICES a copy of the complete a-file belonging to (b)6, (b)7c 04/12/2012 8472 ROSE SANTOS FOIA GROUP, . a copy of the following documents identified to HSHQDC06D00026 Order HSCETC09J00035 1.) All TO modifications 04/12/2012 8473 JORGE LOPEZ-MORENO (b)6, (b)7c GILES everything ICE has in its files pertaining to W. DALBY (b)6, (b)7c CORRECTIONAL FACILITY 04/25/2012 8926 MEG JACOBSON PRITCHETT & a copy of the complete a-file belonging to JACOBSON, P.S. (b)6, (b)7c 04/25/2012 9570 KIP STEINBERG LAW OFFICES a copy of the complete a-file belonging to (b)6, (b)7c 04/25/2012 9766 RICHARD BRACKEN R. BRACKEN & all records regarding (b)6, (b)7c including ASSOC but not limited to: copies of all applications and petitions filed with USCIS, notices, departure records, decisions/denials/approvals, parolled documents, OSC’s, EOIR records, interview records with INS/ICE/USCIS, and RFE’s 04/02/2012 10277 CHRISTINE HASS NBC 7 SAN DIEGO current policy regarding sex hormones for transgendered detainees in ICE custody. The names of the sex hormone medications provided for transgendered detainees and the quantity issued to these detainees from the time period of Jan 2010 to present. -

Cattive Acque Contaminazione Ambientale E Comunità Violate Cattive Acque

A. Zamperini e M. Menegatto e M. Zamperini A. Cattive acque Contaminazione ambientale e comunità violate Cattive acque. Contaminazione ambientale e comunità violate Contaminazione acque. Cattive A cura di Adriano Zamperini e Marialuisa Menegatto Presentazione di Telmo Pievani VA ADO UP P PADOVA UNIVERSITY PRESS Prima edizione 2021, Padova University Press Titolo originale: CATTIVE ACQUE. CONTAMINAZIONE AMBIENTALE E COMUNITÀ VIOLATE © 2021 Padova University Press Università degli Studi di Padova via 8 Febbraio 2, Padova www.padovauniversitypress.it Redazione Padova University Press Progetto grafico Padova University Press ISBN 978-88-6938-243-7 In copertina: foto Marco Carmignan This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY-NC-ND) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/) CATTIVE ACQUE CONTAMINAZIONE AMBIENTALE E COMUNITÀ VIOLATE A cura di Adriano Zamperini e Marialuisa Menegatto Presentazione di Telmo Pievani VA ADO UP P Indice Presentazione 11 Telmo Pievani Introduzione 15 Adriano Zamperini, Marialuisa Menegatto PARTE PRIMA Psicologia sociale dei disastri ecologici Ambiente e violenza 21 Adriano Zamperini Atti di violenza 21 Orientamenti teorici 24 Environmental violence 25 Green criminology 27 Ecological violence 30 Verso una nuova prospettiva psicosociale 32 Violenza 34 Perpetratori 38 Vittime 41 Spettatori 47 Violenza eco-psicologica 50 Disastri tecnologici e conseguenze psicosociali 53 Adriano Zamperini, Marialuisa Menegatto, Sara Lezzi, Michele Musolino Rischio e vita quotidiana 53 Disastri -

Female Rats by Voluntary Exercise

Basic and Clinical September, October 2020, Volume 11, Number 5 Research Paper: Overcomeing Cognitive Impairments of Sleep-deprived Ovariectomized (OVX) Female Rats by Voluntary Exercise Mohammad Amin Rajizadeh1,2 Khadijeh Esmaeilpour2* , Sina Motamedy2 , Fatemeh Mohtashami Borzadaranb2 , Vahid Sheibani1,2* 1. Department of Physiology, School of Medicine, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran. 2. Neuroscience Research Center, Institute of Neuropharmacology, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman, Iran. Use your device to scan and read the article online Citation: Rajizadeh, M. A., Esmaeilpour, Kh., Motamedy, S., Mohtashami Borzadaranb, F., & Sheibani, V. (2020). Cognitive Impairments of Sleep-Deprived Ovariectomized (OVX) Female Rats by Voluntary Exercise. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 11(5), 573-586. http://dx.doi.org/10.32598/bcn.9.10.505 : http://dx.doi.org/10.32598/bcn.9.10.505 A B S T R A C T Introduction: Previous studies demonstrated that forced and voluntary exercise had ameliorative effects on behavioral tasks followed by Sleep Deprivation (SD) in intact female Article info: rats. The main goal of this research was evaluating the impact of voluntary exercise on Received: 11 Aug 2019 cognitive functions while SD and ovariectomization is induced in female wistar rats. First Revision:25 Aug 2019 Methods: The rats were anesthesized combining dosage of ketamine and xylazine. Then, both Accepted: 08 Nov 2019 ovaries were eliminated and 3 weeks after surgery the animals entered the study. The exercise Available Online: 01 Sep 2020 protocol took 4 weeks of voluntary exercise in a wheel which was connected to home cage. For inducing a 72 hours deprivation the multiple platforms was applied. -

Une Analyse À Travers Le Modèle Exigences/Ressources F

Peut-on compenser les conditions de travail contraignantes ? Une analyse à travers le modèle exigences/ressources F. Silveri To cite this version: F. Silveri. Peut-on compenser les conditions de travail contraignantes ? Une analyse à travers le modèle exigences/ressources. Sciences de l’environnement. Doctorat Sciences de Gestion, Université de Montpellier, 2017. Français. NNT : 2017MONTD050. tel-02607274 HAL Id: tel-02607274 https://hal.inrae.fr/tel-02607274 Submitted on 16 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THESE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR DELIVREE PAR L’UNIVERSITÉ DE MONTPELLIER Préparée au sein de l'Ecole Doctorale d'Economie et de Gestion – (ED 231) et de l'unité de recherche Montpellier Research in Management (EA 4557) Spécialité Sciences de Gestion - CNU 06 Peut-on compenser des conditions de travail contraignantes ? Une analyse à travers le modèle exigences/ressources. Présentée par Federica SILVERI Le 15 Novembre 2017 Sous la direction de Sophie MIGNON et Catherine MACOMBE Devant le jury composé de Sophie MIGNON, Professeur des universités., U. de Montpellier Catherine MACOMBE, Dr. HDR, IRSTEA Emmanuel ABORD de CHATILLON, Professeur des universités., U. de Grenoble Alpes Daniele MASCIA, Associate professor, U. -

21. Celostátní Kongres K Sexuální Výchově 2013

21. CELOSTÁTNÍ KONGRES K SEXUÁLNÍ VÝCHOVĚ V ČESKÉ REPUBLICE PARDUBICE 2013 19. – 21. září 2013 Editor: JUDr. Miroslav Mitlöhner, CSc. Editorka: Mgr. Zuzana Prouzová Tento pracovní materiál neprošel autorskou korekturou SBORNÍK REFERÁTŮ 2013 Sborník.indd 271 13.09.13 12:07 21. CELOSTÁTNÍ KONGRES K SEXUÁLNÍ VYCHOVĚ V ČESKÉ REPUBLICEICE PARDUBICE 20132013 SBORNÍK REFERÁTŮ Recenzentka: Doc. PhDr.PhDr. MarieMariie Zouharová,ZoZ uharová, Ph.D. – PPdFdF UP v OlOlomoucioomouci Recenzent: Doc. PaPaedDr.edDr. LaLadislavdislav PPodroužek,odroužek, PhPh.D.h.D. – PPdPdFF ZČZČUU v PlznPlznii EdEditor:iitor: JUDr.JUDr. MiroslavMirosllav Mitlöhner,Mitlöhner, CSCCSc.c.. Editorka:Editorkaa: Mgr.Mgrr. ZZuzanauzana PrPProuzováouzzováá TeTentonto prpracovníaccovo ní materiál neneprošelprošel aautorskouutoro skouu kkorekturouorekturou Sborník.indd 1 13.09.13 12:06 21. CELOSTÁTNÍ KONGRES K SEXUÁLNÍ VYCHOVĚ V ČESKÉ REPUBLICE PARDUBICE 2013 pořádaný Společností pro plánování rodiny a sexuální výchovu Sexuologickou společností ČLK JEP a Ústavem sociální práce Univerzity Hradec Králové VE DNECH 19. – 21. ZÁŘÍ 2013 NA RADNICI V PARDUBICÍCH pod záštitou MUDr. Štěpánky Fraňkové, primátorky města Pardubic a Prof. RNDr. Josefa Hynka, MBA, Ph.D, rektora Univerzity Hradec Králové za podpory Statutárního města Pardubic a dalších partnerů Akreditace MŠMT č. j.: 39 429/2011-25-912 ISBN 978-80-905386-1-0 Sborník.indd 2 13.09.13 12:06 PREZIDENT KONGRESU Doc. MUDr. Peter Koliba, CSc. Gynekologická ambulance Gynartis, s.r.o. ČESTNÉ PŘEDSEDNICTVO Prof. JUDr. Dagmar Císařová, DrSc. vysokoškolská učitelka Právnické fakulty Univerzity Karlovy Praha MUDr. Hanka Fifková sexuoložka, místopředsedkyně SPRSV MUDr. Štěpánka Fraňková, primátorka statutárního města Pardubic MUDr. Miroslav Havlín ženský lékař Prof. RNDr. Josef Hynek, Ph.D., MBA rektor Univerzity Hradec Králové JUDr. -

Conference Proceedings

CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS 14th Annual International Bata Conference for Ph.D. Students and Young Researchers 25/4/2018 1 Conference Proceedings DOKBAT 14th Annual International Bata Conference for Ph.D. Students and Young Researchers Tomas Bata University in Zlín Faculty of Management and Economics Mostní 5139 – Zlín, 760 01 Czech Republic Copyright © 2018 by authors. All rights reserved. Digital publishing – www.dokbat.utb.cz. Published in 2018. Edited by: Ing. et Ing. Monika Hýblová ISBN: 978-80-7454-730-0 DOI: 10.7441/dokbat.2018 The publication was released within the DOKBAT conference, supported by the IGA project No. SVK/FaME/2018/002. Many thanks to the reviewers who helped ensure the quality of the papers. No reproduction, copies or transmissions may be made without written permission from the individual authors. HOW TO CITE: Surname, First Name. (2018). Title. In DOKBAT 2018 - 14th Annual International Bata Conference for Ph.D. Students and Young Researchers (Vol. 14). Zlín: Tomas Bata University in Zlín, Faculty of Management and Economics. Retrieved from http://dokbat.utb.cz/conference-proceedings/ ISBN: 978-80-7454-730-0 CONTENT BUILDING CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP THROUGH THE SOCIAL NETWORKS IN THE FIELD OF E-COMMERCE IN CZECHIA - CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK OF RESEARCH Ottó Bartók ............................................................................................................................. 6 ENTERPRISE PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS OF THE SLOVAK HEALTH SPA SECTOR BY APPLYING SELECTED MODERN FINANCIAL METHODS Veronika Čabinová, Erika -

TEKA Komisji Architektury, Urbanistyki I Studiów Krajobrazowych XIV-2 2018

POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK ODDZIAŁ W LUBLINIE POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BRANCH IN LUBLIN TEKA ISSN 1895-3980 KOMISJI COMMISSION ARCHITEKTURY, OF ARCHITECTURE, TEKA URBANISTYKI URBAN PLANNING I STUDIÓW AND LANDSCAPE KRAJOBRAZOWYCH STUDIES KOMISJI ARCHITEKTURY, URBANISTYKI KRAJOBRAZOWYCH I STUDIÓW ARCHITEKTURY, KOMISJI XIV/2 VOLUME XIV/2 TEKA KOMISJI ARCHITEKTURY, URBANISTYKI I STUDIÓW KRAJOBRAZOWYCH COMMISSION O ARCHITECTURE, URBAN PLANNING AND LANDSCAPE STUDIES POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES BRANCH IN LUBLIN TEKA COMMISSION OF ARCHITECTURE, URBAN PLANNING AND LANDSCAPE STUDIES Volume XIV/2 Lublin 2018 POLSKA AKADEMIA NAUK ODDZIAŁ W LUBLINIE TEKA KOMISJI ARCHITEKTURY, URBANISTYKI I STUDIÓW KRAJOBRAZOWYCH Tom XIV/2 Lublin 2018 Redaktor naczelny prof. dr hab. inż. arch. Elżbieta Przesmycka, Politechnika Wrocławska Rada Naukowa prof. dr hab. arch. Mykola Bevz (Politechnika Lwowska, Ukraina) Rolando-Arturo Cubillos-González (Catholic University of Colombia, Kolumbia) prof. dr hab. Jan Gliński, czł. rzecz. PAN Charles Gonzales (Director of Planning Cataño Ward, Puerto Rico) arch. dipl. ing. (FH) Thomas Kauertz (Hildesheim, Niemcy) dr hab. inż. arch. Jacek Kościuk (Politechnika Wrocławska, Polska) dr. eng. arch. Bo Larsson (Lund, Szwecja) prof. dr hab. inż. arch. Krzysztof Pawłowski (Politechnika Lubelska, Polska) dr Larysa Polischuk (Ivanofrankowsk, Ukraina) prof. dr hab. inż. arch. Elżbieta Przesmycka (Politechnika Wrocławska, Polska) prof. nadzw. dr hab. inż. Krystyna Pudelska (Uniwersytet Przyrodniczy w Lublinie, Polska) prof. dr hab. inż. arch. Petro Rychkov (Rivne University of Technology, Ukraina) prof. Svietlana Smolenska (Charków, Ukraina) Redakcja naukowa tomu XIV/1−4 prof. dr hab. inż. arch. Elżbieta Przesmycka, Politechnika Wrocławska Recenzenci prof. nadzw. dr hab. inż. arch. Andrzej Białkiewicz (Politechnika Krakowska, Polska) prof. dr hab. Mariusz Dąbrowski (Politechnika Lubelska, Polska) dr hab.