PASSOVER READINGS Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Should Bakeries Which Are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? a Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER

Should Bakeries Which are Open on Shabbat Be Supervised? A Response to the Rabinowitz-Weisberg Opinion RABBI HOWARD HANDLER This paper was submitted as a response to the responsum written by Rabbi Mayer Rabinowitz and Ms. Dvora Weisberg entitled "Rabbinic Supervision of Jewish Owned Businesses Operating on Shabbat" which was adopted by the CJLS on February 26, 1986. Should rabbis offer rabbinic supervision to bakeries which are open on Shabbat? i1 ~, '(l) l'\ (1) The food itself is indeed kosher after Shabbat, once the time required to prepare it has elapsed. 1 The halakhah is according to Rabbi Yehudah and not according to the Mishnah which is Rabbi Meir's opinion. (2) While a Jew who does not observe all the mitzvot is in some instances deemed trustworthy, this is never the case regarding someone who flagrantly disregards the laws of Shabbat, especially for personal profit. Maimonides specifically excludes such a person's trustworthiness regarding his own actions.2 Moreover in the case of n:nv 77n~ (a violator of Shabbat) Maimonides explicitly rejects his trustworthiness. 3 No support can be brought from Moshe Feinstein who concludes, "even if the proprietor closes his store on Shabbat, [since it is known to all that he does not observe Shabbat], we assume he only wants to impress other observant Jews so they will buy from him."4 Previously in the same responsum R. Feinstein emphasizes that even if the person in The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. -

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 143 - Having a Secular Name Ou Israel Center - Fall 2019

5779 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 143 - HAVING A SECULAR NAME OU ISRAEL CENTER - FALL 2019 A] WHAT IS A ‘JEWISH NAME’? •There are different levels as to how ‘Jewish’ a name is. Consider the difference between the following: - A Hebrew name from the Tanach 1 eg Avraham, Yehonatan, Esther etc. - A Tanach name which has been shortened or adapted eg Avi, Yoni, Esti, Sari. - A Tanach name which is not normally used - eg Ogli, Mushi, Mupim, Chupim, Ard, Kislon. What about Adam? - The English translation of a Hebrew name eg Abraham, Jonathan, Deborah. - A non-biblical Hebrew name which is commonly used by observant Jews eg Zvi, Ari, Rina, Shira. - A non-Hebrew name which is only used by observant Jews eg Velvel, Mottel, Mendel, Raizel, Sprintze, Kalonimus Kalman. - A non-Jewish name which has been explicitly accepted by Jews - eg Alexander - A non-Jewish name which is commonly used by Jews and non-Jews eg Andrew, Jason, Susan, Lucy. - A non-Jewish name which has connotations relating to other religions eg Paul, Luke, Mary. - A non-Jewish name which is directly connected to another religion eg Chris, Mohammed, Jesus. B] NAMES, WORDS AND REALITY «u¯kt r e h rJt kf u u·kt r e Hv n ,u t r k o ºstvk t tcHu o hºnXv ;ugkF ,t u v s&v ,'H(kF v )nst*vi n ohek,t wv r. Hu 1. (ugcy hpk uk ,utbv una tuv :wuna tuvw aurhpu - e"sr) /u *n J t01v vH( Jp1b o4st*v yh:c ,hatrc At the very outset of creation, the animals were brought to Adam so that he could name them. -

Parshat Tzav

Parshat Tzav Shabbat HaGadol 8 Nissan 5778 / March 24, 2018 Daf Yomi: Avodah Zara 68; Nach Yomi: 2 Shmuel 11 Weekly Dvar Torah A project of the NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG ISRAEL SPONSORED BY THE HENRY, BERTHA AND EDWARD ROTHMAN FOUNDATION ROCHESTER, NY,CLEVELAND, OHIO, CIRCLEVILLE, OHIO Just One Speck Rabbi Shlomo Hochberg Mara D'atra, Young Israel of Jamaica Estates, NY In memory of my beloved father, Rabbi Dr. Hillel Hochberg, z”tl, HaRav Hillel ben Yeshayahu Eliyahu, who passed away Erev Pesach, 14 Nissan 5752. The poem, Chasal Siddur Pesach, popularly known to us as the Nirtzah component of the Hagaddah, actually comprises just the last four lines of a lengthy Halachic Piyyut composed by the Gaon, Rav Yosef Tuv Elem. It is to be said on the morning of Shabbat HaGadol. The Piyyut, Elokai Haruchos L’chol Basar, details the numerous regulations of Pesach preparation. Among the Halachot cited, are the laws of kashering utensils for Pesach, in which Rav Yosef Tuv Elem notes regarding “knives that were used with chometz meals, it is best to make them like new.” The Rav, Moreinu Verabeinu Harav Hagaon Rav Yosef Dov Haleivi Soloveitchik, zt”l, explained that this idea of making them like new is actually a special rule of kashering chometz utensils for Pesach (similar to utensils of Kedoshim, of ritual sacrifices) which does not apply to kashering utensils from traif to kosher. Codified by Maimonides, this rule mandates that, when kashering utensils by hag’alah (purging), the traif utensil becomes kosher as soon as it has been dipped into boiling water. -

Passover Songs

Passover Songs Standing at the Sea by Peter and Ellen Allard Standing at the sea - mi chamocha (3x) Freedom’s on our way. Singing and dancing - mi chamocha (3x) Freedom’s on our way Freedom… The sea she parts… Walking through the water… Freedom… On the other side… *clap* one God… Freedom… Ha Lachma Anya Ha lachma, ha lachma anya Di achalu, achalu avhatana B’ara, b’ara d’Mitzrayim 4 Questions Ma nishtanah ha-lailah hazeh mikol haleilot? Mikol haleilot? Sheb’chol haleilot, anu ochlin chameitz u-matzah? Chameitz u-matzah? Ha-lailah hazeh, ha-lailah hazeh, kulo matzah (2x) Sheb’chol haleilot, anu ochlin sh’ar y’rakot? Sh’ar y’rakot? Ha-lailah hazeh, ha-lailah hazeh, maror, maror (2x) Sheb’chol haleilot, ein anu matbilin afilu pa’am echat? Afilu pa’am echat? Ha-lailah hazeh, ha-lailah ha-zeh, sh’tei f’amim (2x) Sheb’chol haleilot, anu ochlin bein yoshvin u-vein m’subin? Bein yoshvin u-vein m’subin? Ha-lailah hazeh, ha-lailah hazeh, kulanu m’subin (2x) Avadim Hayinu Avadim hayinu, hayinu Ata b’nei chorin, b’nei chorin Avadim hayinu Ata, ata b’nei chorin Avadim hayinu Ata, ata b’nei chorin, b’nei chorin Bang Bang Bang Bang, bang, bang, hold your hammers low, Bang, bang, bang, give a heavy blow For it’s work, work, work, every day and every night, For it’s work, work, work, when it’s dark and when it’s light. Dig, dig, dig, dig your shovels deep, Dig, dig, dig, there’s no time to sleep, For it’s work, work, work, every day and every night, For it’s work, work, work, when it’s dark and when it’s light. -

Download Ji Calendar Educator Guide

xxx Contents The Jewish Day ............................................................................................................................... 6 A. What is a day? ..................................................................................................................... 6 B. Jewish Days As ‘Natural’ Days ........................................................................................... 7 C. When does a Jewish day start and end? ........................................................................... 8 D. The values we can learn from the Jewish day ................................................................... 9 Appendix: Additional Information About the Jewish Day ..................................................... 10 The Jewish Week .......................................................................................................................... 13 A. An Accompaniment to Shabbat ....................................................................................... 13 B. The Days of the Week are all Connected to Shabbat ...................................................... 14 C. The Days of the Week are all Connected to the First Week of Creation ........................ 17 D. The Structure of the Jewish Week .................................................................................... 18 E. Deeper Lessons About the Jewish Week ......................................................................... 18 F. Did You Know? ................................................................................................................. -

Some Highlights of the Mossad Harav Kook Sale of 2017

Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 By Eliezer Brodt For over thirty years, starting on Isru Chag of Pesach, Mossad HaRav Kook publishing house has made a big sale on all of their publications, dropping prices considerably (some books are marked as low as 65% off). Each year they print around twenty new titles. They also reprint some of their older, out of print titles. Some years important works are printed; others not as much. This year they have printed some valuable works, as they did last year. See here and here for a review of previous year’s titles. If you’re interested in a PDF of their complete catalog, email me at [email protected] As in previous years, I am offering a service, for a small fee, to help one purchase seforim from this sale. The sale’s last day is Tuesday. For more information about this, email me at Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of the proceeds will be going to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog. What follows is a list and brief description of some of their newest titles. 1. הלכות פסוקות השלם,ב’ כרכים, על פי כת”י ששון עם מקבילות מקורות הערות ושינויי נוסחאות, מהדיר: יהונתן עץ חיים. This is a critical edition of this Geonic work. A few years back, the editor, Yonason Etz Chaim put out a volume of the Geniza fragments of this work (also printed by Mossad HaRav Kook). 2. ביאור הגר”א ,לנ”ך שיר השירים, ב, ע”י רבי דוד כהן ור’ משה רביץ This is the long-awaited volume two of the Gr”a on Shir Hashirim, heavily annotated by R’ Dovid Cohen. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

Vayigash 5776

Vayigash Vayigash, 7 Tevet 5776 “Sending Everyone Out” Harav Yosef Carmel Before Yosef revealed his identity to his brothers, he commanded the members of his court: “Send everyone out from before me” (Bereishit 45:1). We will try to explain why it was so important to Yosef to be alone with his brothers. The midrash (Sechel Tov, Bereishit 45) explains that this was done for the needs of modesty. As Yosef was going to prove his identity by showing he was circumcised, he did not want his assistants to see what was not necessary for them to see. The simple explanation, of course, is that Yosef wanted to protect his brothers from embarrassment at the awkward situation that was to occur, which would include no small amount of explicit or implicit rebuke. Rishonim put stress on the rebuke, including practical ramifications, stemming from it, other than the brothers’ simple embarrassment. The Ramban says that upon hearing of Yosef’s sale, the Egyptians would view the brothers as betrayers and would reason that if that is the way they treated their own brother, they certainly could not be trusted to live in Egypt and visit in its palace. The Da’at Zekeinim echoes this idea but also extends it, in showing how the matter of the sale was a bigger secret than we might assume. They claim that not only did Yaakov not know about the sale, but even Binyamin, who was not with his brothers at the time, did not know about it. In fact, they claim that Yosef broke his speech of revelation into two. -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

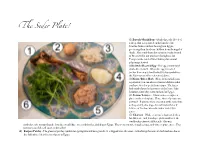

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

Haggadah April 12Th 2020

Community Seder Haggadah April 12th 2020 This Haggadah was prepared by University of Orange and The HUUB for our online community seder on April 12th, 2020. We are celebrating the 130th anniversary of the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Essex County. We have pulled from a few of our favorite haggadahs and made some modifications to the traditional order. We hope to evolve it every year. 1 Seder Activities 1) Opening and Welcome to the First Unitarian Universalist Church of Essex County 130th Anniversary and Seder on Easter 2) Lighting the candles 3) The First Cup of Wine: To Spring 4) Removal of Chametz 5) Song: Zum Gali Gali 6) 6 Symbols of Seder 7) Second cup of wine: To our Ancestors and Teachers 8) The 4 Adults 9) Song: If I Had a Hammer 10) The Telling & The 10 Plagues 11) Third cup of wine: To Resistance, Action, Liberation 12) Elijah’s Cup 13) Miriam’s Cup 14) Song: Dayenu 15) Fourth Cup of Wine: To the Future 2 Opening & Welcome Welcome to our Passover Seder. We made this Haggadah for The HUUB, University of Orange & First Unitarian Universalist Church of Essex County community. It challenges us to connect our history with our present and to act. Let us celebrate our freedom and strengthen ourselves to join the fight against injustice wherever it exists today. For as long as one person is oppressed, none of us are free. The first Pesach was celebrated 3,000 years ago when the people of Israel liberated themselves from the oppression of Egyptian slave masters and began their march toward freedom. -

Psalm 136 MEMORY VERSE PS ALM 136:1 “Oh, Give Thanks to the Lord, for He Is Good! for His M Ercy Endures Forever.”

Lesson 161 Remembering What God Has Done Psalm 136 MEMORY VERSE PS ALM 136:1 “Oh, give thanks to the Lord, for He is good! For His m ercy endures forever.” WHAT YOU WILL NEED: Two small cords or yarn long enough to make a bracelet. Two copies of the “Creation Memory Match Game” curriculum template for each pair of children, white cardstock, crayons and scissors. Butcher paper and markers. ATTENTION GETTER! Memory Bracelets For this activity you will need two small cords or yarn long enough to make a bracelet. Explain to the children that in today’s lesson we are going to learn about the importance of remembering how God has been faithful in our lives. Ask the children to think of several things for which they are thankful. The object will be to tie a not for each thing God had done in their lives to help them to remember. Begin with your bracelet. Have a volunteer help you by holding the ends of two cords. You will hold the other two ends. Explain ways that God has been faithful in your life (for example, “He has provided me with a wonderful family, a good job, helped me in a difficult time, etc.”) Tie a knot for each thing you are thankful for (Optional – place a colorful bead in each knot to make the bracelet more decorative). Leave space between each knot. After sharing four or five things tie the bracelet around your wrist. Have the children split into pairs. Give each child their cords and have them take turns with their partner helping to tie the knots and sharing with each other how God has been faithful in their lives.