The Grain Mirage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinehaven Stream Improvements Archaeological Assessment of Pinehaven Stream Floodplain Management

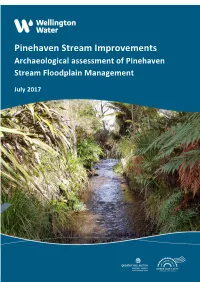

Pinehaven Stream Improvements Archaeological assessment of Pinehaven Stream Floodplain Management July 2017 Archaeological assessment of Pinehaven Stream Floodplain Management for Jacobs Ltd Kevin L. Jones Kevin L. Jones Archaeologist Ltd 6/13 Leeds Street WELLINGTON 6011 [email protected] Wellington 15 July 2017 Caption frontispiece: Pinehaven c. 1969 viewed from the north. Trentham camp mid-left, St Patricks (Silverstream) College at right. Pinehaven Stream runs across the centre of the photograph. Source: Hutt City Library. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This assessment reviews the risk of there being archaeological sites as defined in the Heritage NZ Pouhere Taonga Act 2014 in the vicinity of the works proposed for the Pinehaven Stream. The geomorphology of the area has been reviewed to determine whether there are older land surfaces that would have been suitable for pre-European or 19th C settlement. Remnant forest trees indicate several areas of older but low-lying (flood-prone) surfaces but field inspections indicate no archaeological sites. A review of earlier (1943) aerial photographs and 19th C survey plans indicate no reasonable cause to suspect that there will be archaeological sites. A settlement established in 1837 by Te Kaeaea of Ngati Tama in the general area of St Patricks College Silverstream is more or less on the outwash plain of the Pinehaven Stream. The fan north of the college is heavily cut into by the edge of the Hutt valley flood plain. This is the only historically documented 19th C Maori settlement on the Pinehaven Stream fan but it is outside the area of proposed works. Another broad class of archaeological site may be earlier forms of infrastructure on the stream such as dams, mills, races, bridges, abutments, and logging and rail infrastructure. -

Report of Ministerial Committee of Inquiry Into Violence

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. CIC~r S~:2. -9Y i;, ~: Report of Ministerial Committee of Inquiry into Violence 108665 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This documenl has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points 01 view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official posilion or pOlicies 01 the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrightetl material has been granted by Department of Justice, Wellington, New Zealand .. to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis· sian of the copyright owner. Presented to the Minister of Justice March 1987 iOReport of Ministerial Committee of Inquiry in~o Violence "'---, Presented to the Minister of Justice March 1987 COMMITTEE OF INQUIRY INTO VIOLENCE Chairman Sir Clinton Roper of Christchurch, Retired Judge of the High Court Members Mr M. R. D. Guest of Dunedin, Barrister and Solicitor and Dunedin City Councillor since 1977. Mrs A. Tia Q.S.M., J.P. of Auckland with a long history in community and youth social work. Dr A. P. McGeorge of Auckland, Psychiatrist and Familv therapist, Director of the Adolescent Unit of Auckland Hospital Board. Mrs B. E. Diamond of Wellington, teacher for 20 years and Senior Mistress at Wainuiomata College. Sir Norman Perry M.B.E. of Opotiki, member of the East Coast Regional Development Council and consultant to the Whakatohea Maori Tribal Authorities on rural industry and work trusts. -

Māori Election Petitions of the 1870S: Microcosms of Dynamic Māori and Pākehā Political Forces

Māori Election Petitions of the 1870s: Microcosms of Dynamic Māori and Pākehā Political Forces PAERAU WARBRICK Abstract Māori election petitions to the 1876 Eastern Māori and the 1879 Northern Māori elections were high-stakes political manoeuvres. The outcomes of such challenges were significant in the weighting of political power in Wellington. This was a time in New Zealand politics well before the formation of political parties. Political alignments were defined by a mixture of individual charismatic men with a smattering of provincial sympathies and individual and group economic interests. Larger-than-life Māori and Pākehā political characters were involved in the election petitions, providing a window not only into the complex Māori political relationships involved, but also into the stormy Pākehā political world of the 1870s. And this is the great lesson about election petitions. They involve raw politics, with all the political theatre and power play, which have as much significance in today’s politics as they did in the past. Election petitions are much more than legal challenges to electoral races. There are personalities involved, and ideological stances between the contesting individuals and groups that back those individuals. Māori had to navigate both the Pākehā realm of central and provincial politics as well as the realm of Māori kin-group politics at the whānau, hapū and iwi levels of Māoridom. The political complexities of these 1870s Māori election petitions were but a microcosm of dynamic Māori and Pākehā political forces in New Zealand society at the time. At Waitetuna, not far from modern day Raglan in the Waikato area, the Māori meeting house was chosen as one of the many polling booths for the Western Māori electorate in the 1908 general election.1 At 10.30 a.m. -

Roll of Members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 Onwards

Roll of members of the New Zealand House of Representatives, 1854 onwards Sources: New Zealand Parliamentary Record, Newspapers, Political Party websites, New Zealand Gazette, New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), Political Party Press Releases, Appendix to the Journal of the House of Representatives, E.9. Last updated: 17 November 2020 Abbreviations for the party affiliations are as follows: ACT ACT (Association of Consumers and Taxpayers) Lib. Liberal All. Alliance LibLab. Liberal Labour CD Christian Democrats Mana Mana Party Ch.H Christian Heritage ManaW. Mana Wahine Te Ira Tangata Party Co. Coalition Maori Maori Party Con. Conservative MP Mauri Pacific CR Coalition Reform Na. National (1925 Liberals) CU Coalition United Nat. National Green Greens NatLib. National Liberal Party (1905) ILib. Independent Liberal NL New Labour ICLib. Independent Coalition Liberal NZD New Zealand Democrats Icon. Independent Conservative NZF New Zealand First ICP Independent Country Party NZL New Zealand Liberals ILab. Independent Labour PCP Progressive Coalition ILib. Independent Liberal PP Progressive Party (“Jim Anderton’s Progressives”) Ind. Independent R Reform IP. Independent Prohibition Ra. Ratana IPLL Independent Political Labour League ROC Right of Centre IR Independent Reform SC Social Credit IRat. Independent Ratana SD Social Democrat IU Independent United U United Lab. Labour UFNZ United Future New Zealand UNZ United New Zealand The end dates of tenure before 1984 are the date the House was dissolved, and the end dates after 1984 are the date of the election. (NB. There were no political parties as such before 1890) Name Electorate Parl’t Elected Vacated Reason Party ACLAND, Hugh John Dyke 1904-1981 Temuka 26-27 07.02.1942 04.11.1946 Defeated Nat. -

Petone (Pitone)

Petone (Pitone) 1881-1882 1882 62 Petone Joplin Charles R Master £230.00 1882 62 Petone Stevens Ella Female Pupil Teacher £40.00 21st February 1881 A MEETING of Householders will take place at Riddler’s Building, Petone, on TUESDAY EVENING, 22nd February, at 7.30 p.m., to consider School Site. 28th April 1881 Wellington Education Board The Ven. Archdeacon Stock reported that he had written to the Hon. Mr. Dick on the subject of the Petone school site, and that he had received a very courteous reply, to the effect that there was no other piece of Government land that was suitable for school purposes ; all the remainder of the ground was either swampy or otherwise unavailable. 1st December 1881 Wellington Education Board A petition was received from twenty residents of Petone, praying that the district be declared a separate school district. The Inspector stated that the Hutt School Committee offered no objection. The petition was acceded to. 7th January 1882 Master for the new school in temporary room, Petone ; salary according to scale. 25th January 1882 A meeting of householders was held at Petone last night for the purpose of electing the school committee for that district. The following were elected :— Messrs. Manning, Jackson, Calvert, Buick, Curtiss, Park, and Kirk 4th February 1882 Wellington Education Board Petone: Mr C R Joplin appointed. (Promoted from Lower Hutt) 23rd February 1882 Wellington Education Board Petone, site and school, £6OO 25th February 1882 Wellington Education Board Wanted Pupil Teacher 8th March 1882 Petone School, Miss Archer (from Mount Cook Boys 1 School) 1st June 1882 Wellington Education Board Dr. -

CRICKET MUSEUM History, and Monique Damitio, a Computer Scientist from in the End, a Nine-Wicket Victory to Dates in Cricket History up to 1882

EDUCATION EXHIBITIONS / DISPLAYS Daniel Vettori Test Match Report 3rd Test, New Zealand v. Australia, ‘Start of Play: The Origins of Cricket’ rd Eden Park 2005 Commencing 12 September 2005 In late March the Museum Curator attended the 3 New Zealand Photo: Photosport, March 2005 NEW ZEALAND verses Australia test match at Eden Park, Auckland, with Collection: New Zealand Cricket This display will feature texts on What is Cricket?; Origins of the Game; The Bat; The J. Neville Turner, President of the Australian Society for Sports Ball; Stumps, Bails and Pitch; Bowling; Scoring and a panel highlighting significant CRICKET MUSEUM History, and Monique Damitio, a computer scientist from In the end, a nine-wicket victory to dates in cricket history up to 1882. Also, pictorial images of early cricket and cricketers, Morocco who lives in France. He invited both of his guests to Australia was a somewhat flattering re-enacted moving image material of a cricket match being played in England in the contribute an article for the newsletter. Neville has responded margin. If not a great test match, it was, late 18th Century, plus film archive material transferred to DVD and sound archive with the following edited report of the test match. in my judgement, a richly exhilarating material transferred to CD. one. ‘Auckland is a majestic city, a small compact, narrow area ‘Etymological scholarship has variously placed the game in the Celtic, Scandinavian, bounded by both the Tasman and the Pacific seas. Eden Park is And my own exhilaration was greatly Anglo-Saxon, Dutch and Norman-French traditions; sociological historians have some distance from the centre of the city. -

21 and 22 Victoriae 1858 No 55 Electoral Districts

.. NEW ZEALAND. 4NNO VICESIMO PRIMO ET VICESIMO SECUNDO VICTORI~ REGIN~, No. 55. ANALYSIS: Title. tered to hold .eats Cor new di4tri,ts of Preamble. eame name. 1. Number of Membera ofHouseoC Represen- 6. Electoral RoDs to be fOJ'Dled lor new and tatives. divided districts. I. Number of Eleetoral districts; 1. Mode ofCorming ElectQral Bolls. s. Description of districts. 8. Rolls to be pabfished • .t. Present Members to hold seats. 9. When Writs to.be issued. Li. Members of the present districts now aI. 10. Short Title. AN ACT to constitute Electoral Districts Tille~ for the Election of Members of the House of Representatives~ [19th August, 185.8.1 BE IT -ENACTED by the General Assen:bly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:- I. The House of R~presentatives for New Zealand· shall :'Wo~e:e~:::~:~~ consist of 41 ~emb~rs. tatives. II.. For the purposes of the election of the members of the Number of Electoral said House, the Colony shall be divided into 28 Electoral District,. Districts, the names of which, and the number of members to be returned by which respectiv.ely, shall. be as follows ~- . 1. Bay of Islands, 1 Member~ 2. Marsden, 1 Member. 3. Northern Division, 2 Members. ~. City of Auckland, 3 Members: .. • 354 21° & 22° VICTORI~, No. 55. Electoral Districts. 5. Suburbs of Auckland, 2 Members. 6. Pensioner Settlements, 2 Members. 7. Southern Division, 2 Members. 8. Town of New Plymouth, 1 Member. 9. Grey and Bell, 1 Member. 10. Ornata, 1 Member. 11. -

Miscellaneous Exhibits – Unidentified

Pandora Research www.nzpictures.co.nz Miscellaneous exhibits – unidentified Archives NZ Reference ADXS 19552 LS-W 62/32 Note: The following is presented in the respective order of the papers found in this file Conveyance Alexander Kennedy of Auckland, Banker and Manager of the New Zealand Banking Company at Auckland to Robert Jenkins of Wellington, licensed victualler dated 13 Sep 1845. Refers to: [1] Deed dated 13 Jun 1842 John Wade conveyed Town section 488 to Jabez Allen; [2] Indenture date 01 Dec 1842 between John Wade and William Mayhew; [3] Deed dated 30 Aug 1843 between William Mayhew and Alexander Kennedy. “…that the said William Mayhew was indebted to the New Zealand Banking Company £2,000 which he was then unable to discharge and pay…” The property was “put up for sale by Public Auction at the Office of Kenneth Bethune and George Hunter… at which sale the said Robert Jenkins was the highest bidder… at the sum of £48. The document includes a coloured plan showing Lambton Quay, Wellington Terrace and includes reference to McLaggan on south border. Land Transfer Certificate No.738. These are to certify, that a Notice of the Transfer of the New Zealand Company’s Preliminary Land Order, No.52, as far as regards the Town Acre at the Settlement of Wellington from Jonathan Crowther of Halifax Esquire to John Stott of Greetland near Halifax hath been deposited in the office of the New Zealand Company in London, and registered in the books of the said Company 18 Dec 1845. John Stott – Preliminary Land order 52 Parts 1 & 2 & Land Transfer Certificate of Town Acre. -

33 and 34 Victoriae 1870 No 15 Representation

NEW ZEALAND. TRICESIMO TERTIO ET TRICESIMO QUARTO VIC,TORI-LE REG IN-LE. No. XV. ************************************************************ ANALYSIS. Title. 7. New rolls not to be formed for unaltered 1. Short TiLle. districts. 2. House to consist of seventy-four Members. 8. New rolls to be formed for altered districts. 3. Sixty-eight Electoral Districts established. 9. Mode of forming new rolls. 4. Number of Members for each district. 10. Publication and eft'act of rollo. 5. Maps of distriets to be made. 11. Time of issue of writs. 6. Rolls to be completed for the Electoral Dis· 12. If necessary, Governor may issue writs for a tricts as existing immediately before this new Parliament without, referenc~ to this Act. Act. AN ACT to make further prOVIsIon for the Repre- Title. sentation of the People of New Zealand in Parliament. [12th September 1870.] E IT ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same B as follows- 1. The Short Title of this Act shall be "The Representation Short Title. Act 1870." . 2. After the Dissolution of the present Parliament the House of House to conais' Representatives shall consist of seventy-four Members over and be- °Mf seTbenty.four • •• em ers. yond the four Members to be elected for the MaorI Electoral DIstrlCts under the provisions of "The Maori Representation Act 1867." 3. For the purposes of the election of the said number of Si;rty:eight Ele?toral Members of the said House the Colony shall be divided into sixty- DIstrlCts estabbshed. eight Electoral Districts as the same are respectively named defined and set forth in the Schedule to this Act. -

In the Matter of Waitangi Tribunal Claim 145 "The Crown Could Not

ai I 1 In the matter of Waitangi Tribunal Claim 145 "The Wellington Tenths" "The Crown Could Not Grant What the Crown Did Not Possess" Land Commissioner William Spain Interim Report, WAI 145 Doc. A10(a)5:5 September 1843 Submitted by Duncan Moore 2 March 1992 1 Contents Introduction and Summary ...................................... 1 Lands Lost to Crown Around 1850 ..................... ...... 6 Arguments for the Existence of Reserves ...................... 7 A Perspective on the Creation of Reserves . .. 15 The Broad Terrain ........................ ................... 21 Abandoning the Land Claims Inquiry ........................ 27 The Track of Agreement ................................. ..... 32 A Single Meaningful Agreement ......................... .. 41 A Lasting Possession ......................................... 53 Acting Upon Principles .................................. 69 78 Changes Back Home .................................... 84 A Sea-Change ......................................... 88 The Constitution in Wellington ............................ 92 Preparing to Grant ................. .................... 103 The Port Nicholson Crown Grant ........................... 107 The Grant Debacle ..................................... 113 The Expropriation of Native Reserves for Public Purposes .............. 117 Military Seizures ....................................... 122 Getting Better Tenants ............... ................... 126 "One Slice at a Time" ................................... 130 Granting Reserves Away ................................ -

35 Victoriae 1871 No 59 Representation Act Amendment

257 . NEW ZEALAND. TRICESIMO QUINTO VICTORI-LE REGIN-LE. No. LIX. *********************************************************** ANALYSIS. 5. Registration and Returning Officers to remain in Title. office for Districts as re·defined. Preamble. 6. Mode of forming new rolls. 1. Short Title. 7. Publication and effect of llew rolls. 2. Schedule annexed to this Act to be substituted in 8. Each sitting Member for District constituted by " Representation Act 1870" for the Sched ule the said Act to be Members for Districts all thereto annexed. defined in substituted Schedule and bearing 3. Interpretation of "Representation Act 1870." same name. 4. Maps to be prepared. Schedule. AN ACT to correct the Descriptions of the Boundaries of Titltt. the Electoral Districts for the election of Members of the House of Representatives. [14tlz November 187'1.] HEREAS many errors have been discovered in the descriptions Preamble. of the boundaries of the Electoral Districts set forth in the W Schedule to "The Representation Act 1870" hereinafter referred to as "the said Act" and it is expedient to correct the same by amending the said Act in the manner hereinafter provided : BE IT THEREFORE ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled and by the authority of the same as follows :- 1. The Short Title of this Act shall be "The Representation Act Short Title. Amendment Act 1871." 2. The Schedule to this Act annexed is hereby substituted in the Schedule annexed to said Act ,for th~ Schedule thereto annexed. The Schedule to this Act :::t~~t?'~e;:e~:~: annexed IS herem referred to as "the substltuted Schedule." tation Act 1870" for 3. -

Download PDF Catalogue

Catalogue No.157 ART + OBJECT Rare Books 09.12.20 AO1579FA Cat157 Rare Books cover.indd All Pages 18/11/20 11:28 AM 69 55 53 257 126 127 132 146 145 147 148 153 151 152 149 162 154 156 160 RARE BOOKS AUCTION 157 Wednesday 9 December 2020 at 12pm NZT VIEWING Friday 4 December 9.00am – 5.00pm Saturday 5 December 11.00am – 4.00pm Sunday 6 December 11.00am – 4.00pm Monday 7 December 9.00am – 5.00pm Tuesday 8 December 9.00am – 5.00pm After an uncertain year, our final auction for 2020 will be held on Wednesday, 9th of December. The sale is a small but interesting collection featuring some early and rare items including “A Deed of Conveyance” dated 6th December 1839, transferring parcels of land near Cape Farewell, between Maori Chiefs and ‘an English Gentleman’. Other rare items include a late-18th century watercolour of the native tui, titled verso ‘Tuee‘. A first-hand account dated 1879 of ‘The wreck of the Harriet’ off the coast of Taranaki by Robert Leeds Sinclair. First editions by Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin and J.R.R. Tolkien. A strong collection of historic New Zealand photography and stereoscopic cards that include 1901 America’s Cup and the Boer War. Our usual selection of Maori and New Zealand histories; art and private press books; science fiction; and literature including signed works by Janet Frame. Other interesting items include a Bastion Point Poster May 25, 1978, signed by Tim Shadbolt. A large collection of vintage fountain & ball point pens & retractable pencils by Parker, Watermans, Cross, Sheaffer, Aurora, Mont Blanc and others.