Legislative Neutrality in the United States C.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nixon Theory of the War Power: a Critique

California Law Review VOL. 60 MAY 1972 No. 3 The Nixon Theory of the War Power: A Critique Francis D. Wormuth* On March 11, 1966, the Legal Adviser of the State Department, Leonard Meeker, submitted to the Senate Committee on Foreign Rela- tions a memorandum that, despite its brevity, proved to be the fullest statement ever made of the legal case for the initiation of war in Viet- nam by President Johnson.' He offered several arguments. The framers of the Constitution had qualified the war clause. They in- tended that the President be free to repel sudden attacks upon the United States without Congressional authorization; with the shrinking of the globe this exception had grown into a power to repel an attack on any country, even one halfway around the earth, if he considered this necessary to safeguard American interests. One hundred twenty- five historic cases of unauthorized executive use of military force sup- plied validating precedents for Johnson's action. The Tonkin Gulf Resolution authorized the President to make war at will in Southeast Asia. The SEATO Treaty authorized him to defend Southeast Asia against Communism. And, finally, by passing appropriation acts, the Congress had endorsed the war. President Nixon, even while withdrawing troops from Vietnam, has continued to commit more troops in smaller numbers. Similarly, he has withdrawn some of the legal justifications adduced by Meeker but has advanced others to replace the arguments that have been re- * Professor of Political Science, University of Utah. A.B. 1930, M.A. 1932, Ph.D. 1935, Cornell University. 1. Meeker, The Legality of United States Participationin the Defense of Viet- Nam, 54 DEP'T STATE BuLL. -

A Bridge Across the Pacific: a Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 1-7-2016 A Bridge Across the Pacific: A Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East Michael Todd Gagle Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gagle, Michael Todd, "A Bridge Across the Pacific: A Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East" (2016). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2655. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2651 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Bridge Across the Pacific A Study of the Shifting Relationship Between Portland and the Far East in the 1930s by Michael Todd Gagle A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Kenneth Ruoff, Chair Desmond Cheung David Johnson Jon Holt Portland State University 2015 © 2015 Michael Todd Gagle Abstract After Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, both Japan and China sought the support of America. There has been a historical assumption that, starting with the hostilities in 1931, the Japanese were maligned in American public opinion. Consequently, the assumption has been made that Americans supported the Chinese without reserve during their conflict with Japan in the 1930s. -

1 Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76648-7 - The Doctrines of US Security Policy: An Evaluation under International Law Heiko Meiertons Excerpt More information 1 Introduction ‘Right’ and ‘might’ are two antagonistic forces representing alternative principles for organising international relations. Considering the inter- action between these two forces, one can identify certain features: with regard to questions considered by states as being relevant or having vital importance to their own security international law serves as means of foreign policy, rather than foreign policy serving as a means of fostering international law.1 Given the nature of international law as a law of coordination and also the way in which norms are created under it, pre-legal, political questions of power are of far greater importance under international law than they are under domestic law.2 Despite an increasing codification of international law or even a constitutionalisation,3 international law lacks a principle which contradicts the assumption that states, based on their own power may act as they wish.4 In spite of the principle of sovereign equality, the legal relations under international law can be shaped to mirror the distribution of power much more than in domestic law.5 1 H. Morgenthau, Die internationale Rechtspflege, ihr Wesen und ihre Grenzen (Leipzig: Universitatsverlag¨ Robert Noske, 1929), also: Ph.D. thesis, Leipzig (1929), pp. 98–104; L. Henkin, How Nations Behave – Law and Foreign Policy (New York: Praeger, 1968), pp. 84–94. 2 F. Kratochwil, ‘Thrasymmachos Revisited: On the Relevance of Norms and the Study of Law for International Relations’, J.I.A. -

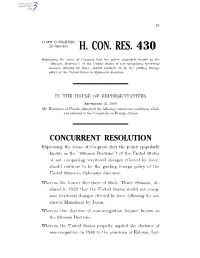

H. Con. Res. 430

IV 110TH CONGRESS 2D SESSION H. CON. RES. 430 Expressing the sense of Congress that the policy (popularly known as the ‘‘Stimson Doctrine’’) of the United States of not recognizing territorial changes effected by force, should continue to be the guiding foreign policy of the United States in diplomatic discourse. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES SEPTEMBER 25, 2008 Mr. HASTINGS of Florida submitted the following concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Expressing the sense of Congress that the policy (popularly known as the ‘‘Stimson Doctrine’’) of the United States of not recognizing territorial changes effected by force, should continue to be the guiding foreign policy of the United States in diplomatic discourse. Whereas the former Secretary of State, Henry Stimson, de- clared in 1932 that the United States would not recog- nize territorial changes effected by force following the sei- zure of Manchuria by Japan; Whereas this doctrine of non-recognition became known as the Stimson Doctrine; Whereas the United States properly applied the doctrine of non-recognition in 1940 to the countries of Estonia, Lat- VerDate Aug 31 2005 23:03 Sep 26, 2008 Jkt 069200 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6652 Sfmt 6300 E:\BILLS\HC430.IH HC430 rwilkins on PROD1PC63 with BILLS 2 via, and Lithuania and every Presidential administration of the United States honored this doctrine until inde- pendence was restored to those countries in 1991; Whereas article 2, paragraph 4 of the Charter of the United Nations demonstrates -

Japanese - American Relations, 1941: a Preface to Pearl Harbor

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-1966 Japanese - American Relations, 1941: A Preface to Pearl Harbor Edward Gorn Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Gorn, Edward, "Japanese - American Relations, 1941: A Preface to Pearl Harbor" (1966). Master's Theses. 3852. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3852 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAPANESE - AMERICAN RELATIONS,- 1941: A PREF ACE TO PEARL HARBOR by Edward Gorn A thesis presented to the Faculty of the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 1966 PREFACE There are as many interpretations as there are writers on the positions of American foreign policy during the diplomatic negotia tions with Japan in 1941. Hi.storians supporting President Roosevelt's 1 position tend to blame Japan s imperialism and expansionism as one of the main causes of the war. Revisionist historians like Charles Beard, Harry Elmer Barnes, and Charles Tansill, place the responsibility for Japan's declaration of war and surprise attack on the intransigent approach of the Roosevelt administration. To place the full burden of responsibility for the failure of negotiations on either Japan or the United States is to over--simplify the complex events of 1941. -

Sea Power in Its Relations to the War of 1812

UNIVERSITY -5^ LIBRARY DATE DUE w^trt ^^m^^ Uj^Sd^Mi^* PRINTED IN U.S. A Cornell University Library E 354.M21 Sea power in its relations to the War of 3 1924 006 126 407 SEA POWER IN ITS EELATIONS TO THE WAR OF EIGHTEEN HUNDRED AND TWELVE VOLUME I SEA POWER IN ITS RELATIONS TO THE WAR OE 1812 CAPTAIN A. T. MAHAN, D.C.L., LL.D. SlniteB State Nabg AUTHOR OF "THE INFLUENCE OF SEA POWEE UPON HISTORY, 1660-1783," "THE INFLUENCE OF SEA POWER UPON THE FRENCH REVOLUTION ANI> EMPIRE," " THE INTEREST OF AMERICA IN SEA POWER," ETC. IK TWO VOLUMES VOL. I BOSTON LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY 1905 > 2 5^ V.I Copyright, 1903, 1904, By Charles Scribnek's Sons. Copyright, 1905, By a. T. Mahan. All rights reserved Published October, 1905 c o THE DNTVEKSITY PRESS CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A. PREFACE present work concludes the series of " The THEInfluence of Sea Power upon History," as originally framed in the conception of the author. In the previous volumes he has had the inspir- ing consciousness of regarding his subject as a positive and commanding element in the history of the world. In the War of 1812, also, the effect is real and dread enough ; but to his own country, to the United States, as a matter of national experience, the lesson is rather that of the influence of a negative quantity upon national history. The plirase scarcely lends itself to use as a title ; but it represents the truth which the author has endeavored to set forth, though recognizing clearly that the victories on Lake Erie and Lake Champlain do illustrate, in a distinguished manner, his principal tliesis, the controlling influence upon events of naval power, even when transferred to an inland body of fresh water. -

Public Lecture

1 International Forum on Diplomatic Training 2016 43rd Meeting of Deans and Directors of Diplomatic Academies and Institutes of International Relations Public Lecture Slide 1 [Delivered on Tuesday, 20 September 2016, at The Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy, Hedley Bull Centre, Australian National University, Canberra] 2 Annotated Presentation Amidst the current discussion of “rising” powers in Asia and the Pacific Ocean, I am mindful, as a diplomatic historian, that the United States was a rising power in the region once too . Is it still rising, one is tempted to ask, or has it become an “established,” even status quo power? Or is it now a “declining” power, relative to the movement of others, if not in a physical, absolute sense? The stakes implied by the question of the U.S. power status are high, for there is an attendant question involving the Asia-Pacific region as a whole, if not the entire world: namely, that of whether a marked rise in the power of one country in terms of military and economic strength and political influence, alongside that of other countries in a regional international system, is inherently conflictual—and even likely to result in war. There is a currently fashionable idea, formulated mainly by political scientists though, to be sure, based on the comparative analysis of relevant cases from the past, that power discrepancies, particularly when levels are unstable and can shift, are in themselves causes of conflict. An especially effective presentation of this idea, termed “The Thucydides Trap,” is that of Graham Allison and his colleagues in the Belfer Center at the Harvard Kennedy School. -

Emp, An& Juapoleon

gmertca, , ?|emp, an& JUapoleon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 BY ALFRED W. CROSBY, JR. Ohio Sttite University Press $6.50 America, IXuaata, S>emp, anb Napoleon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 BY ALFRED W. CROSBY, JR. On the twelfth of June, 1783, a ship of 500 tons sailed into the Russian harbor of Riga and dropped anchor. As the tide pivoted her around her mooring, the Russians on the waterfront could see clearly the banner that she flew — a strange device of white stars on a blue ground and horizontal red and white stripes. Russo-American trade had irrevocably begun. Merchants — Muscovite and Yankee — had met and politely sounded the depths of each other's purses. And they had agreed to do business. In the years that followed, until 1812, the young American nation became economically tied to Russia to a degree that has not, perhaps, been realized to date. The United States desperately needed Russian hemp and linen; the American sailor of the early nineteenth century — who was possibly the most important individual in the American economy — thought twice before he took any craft not equipped with Russian rigging, cables, and sails beyond the harbor mouth. To an appreciable extent, the Amer ican economy survived and prospered because it had access to the unending labor and rough skill of the Russian peasant. The United States found, when it emerged as a free (Continued on back flap) America, Hossia, fiemp, and Bapolcon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 America, llussia, iicmp, and Bapolton American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1811 BY ALFRED W. -

Of Manchukuo in Chinese Manchuria in the Early 1930S

INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION OF THE JAPANESE “PUPPET STATE” OF MANCHUKUO IN CHINESE MANCHURIA IN THE EARLY 1930S by Emily Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of History Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 8, 2017 1 INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION OF THE JAPANESE “PUPPET STATE” OF MANCHUKUO IN CHINESE MANCHURIA IN THE EARLY 1930S Project Approved: Supervising Professor: Peter Worthing, Ph.D. Department of History William Meier, Ph.D. Department of History Mark Dennis, Ph.D. Department of Religion 2 ABSTRACT In September 1931, an explosion occurred on the Southern Manchurian Railroad line near the city of Mukden in the Chinese province of Manchuria. In response to the attack, the Japanese army stationed in Korea at the time moved into Manchuria and annexed the territory from China. This turn of events did concern the international community, but no decisive action was taken during the rest of 1931. The only nation to create any sort of policy regarding the Japanese actions in Manchuria was the United States, which created the Stimson Doctrine in December 1931. The Stimson Doctrine stated that the United States would not recognize new states that were created by aggressive actions, in many ways predicting what would happen in 1932. In early 1932, a new nation called Manchukuo was established in the region with Japan supporting its independence from China. The international community was shocked by these developments and the League of Nations established the Lytton Commission to investigate the Mukden incident and the validity of the new Manchurian State. The League of Nations, however, was slow in its response to the issue of recognizing Manchukuo as an independent nation with it taking over a year for the League to declare that it would not recognize the new state. -

Defining and Punishing Offenses Under Treaties

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2015 Defining and Punishing Offenses Under Treaties Sarah H. Cleveland Columbia Law School, [email protected] William S. Dodge Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, International Law Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation Sarah H. Cleveland & William S. Dodge, Defining and Punishing Offenses Under Treaties, 124 YALE L. J. 2202 (2015). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/235 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TH AL LAW JOURAL SARAH H. CLEVELAND & WILLIAM S. DODGE Defining and Punishing Offenses Under Treaties ABSTRACT. One of the principal aims of the U.S. Constitution was to give the federal gov- ernment authority to comply with its international legal commitments. The scope of Congress's constitutional authority to implement treaties has recently received particular attention. In Bond v. United States, the Court avoided the constitutional questions by construing a statute to respect federalism, but these questions are unlikely to go away. This Article contributes to the ongoing debate by identifying the Offenses Clause as an additional source of Congress's constitutional authority to implement certain treaty commitments. Past scholarship has assumed that the Arti- cle I power to "define and punish... Offences against the Law of Nations" is limited to custom- ary international law. -

07/14/17 Farm Directionанаvantrump

Tim Francisco <[email protected]> GOOD MORNING: 07/14/17 Farm Direction VanTrump Report 1 message Kevin Van Trump <[email protected]> Fri, Jul 14, 2017 at 7:27 AM To: Kevin Van Trump <[email protected]> “Ring the bells that still can ring. Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.” — Leonard Cohen FRIDAY, JULY 14, 2017 Printable Copy or Audio Version Morning Summary: Stocks continue to make minor gains and once again push the Dow to another record high close yesterday. Investors are anxiously waiting for the start of second quarter earnings, which kickoff today with results scheduled from JP Morgan Chase, Wells Fargo and Citigroup. Bank earnings were very strong last quarter, but several insiders believe major banks are actually going to see a decline in year overyear earnings in the secondquarter. Some reasons cited for the gloomy outlook include decreased trading revenues amid the extremely low volatility witnessed in bond and equity markets over that time period. I personal don't see big bank earnings being impacted and remain bullish the banking sector. For the S&P 500 Index as a whole, total Q2 earnings are expected to be up +5.6% from the same period last year on +4.5% higher revenues. Sectors with the strongest growth in Q2 include Energy, Technology, Aerospace, Construction and Industrial Products. Some of the earnings highlights coming up next week include Abbott Labs, American Express, Bank of America, BlackRock, Capital One, ColgatePalmolive, CSX, Ebay, General Electric, Goldman Sachs, IBM, Kinder Morgan, Lockheed Martin, Microsoft, Netflix, Novartis, United Health, Visa and Yahoo. -

United States V. Klintock: Reconsideration of United States V. Palmer As to General Piracy As Defined

FOREWORD Title United States v. Klintock: Reconsideration of United States v. Palmer as to General Piracy as Defined by the Law of Nations through the Applicable Standards of Political Action of Acknowledgement and Recognition and the Status of Statelessness. Author Justin L. Sieffert Document Type Article Publication Date December 2016 Keywords 1820, Piracy, General Piracy, “Law of Nations,” Privateer, Pardon. Abstract During the February 1820 Term, the Supreme Court of the United States decided four significant piracy cases, beginning with United States v. Klintock. Political, economic, and social pressures enhanced the problem of piracy affecting the interests of the United States. Responding to the criticism of his decision in United States v. Palmer and the passage of the Act of 1819 state Congressional intent for defining piracy by the “law of nations,” Marshall authored the decision in Klintock distinguishing Palmer and, upon reconsideration, interpreting the Act of 1790 to include general piracy as defined by the “law of nations.” With a broader interpretation, federal courts had the jurisdiction to consider cases of general piracy regardless of the character of the vessel or nationality of the offender if the vessel operated under the flag of an unacknowledged foreign entity and if an American interest was at issue. While serving as the foundation for the final three piracy cases to endure broad enforcement authority over piracy, the story of Klintock did not end with the decision. An internal controversy over missing evidence in the case due to an alleged conspiracy implicated other parties in the piracy and demonstrated the internal policies and political considerations Monroe administration in the aftermath of the piracy cases.