Stew Onboard Ship in the 16Th Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

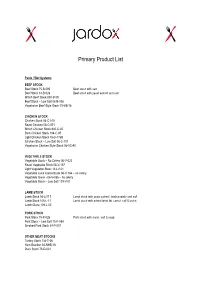

Primary Product List

Primary Product List Paste / Wet Systems BEEF STOCK Beef Stock 75-B-095 Beef stock with salt Beef Stock 14-B-028 Beef stock with yeast extract and salt British Beef Stock 800-B-09 Beef Stock – Low Salt 06-B-038 Vegetarian Beef Style Stock 75-VB-16 CHICKEN STOCK Chicken Stock 06-C-015 Roast Chicken 06-C-071 British Chicken Stock 800-C-02 Dark Chicken Stock 104-C-97 Light Chicken Stock 75-C-173B Chicken Stock – Low Salt 06-C-107 Vegetarian Chicken Style Stock 06-VC-40 VEGETABLE STOCK Vegetable Stock – No Celery 06-V-022 Roast Vegetable Stock 06-V-157 Light Vegetable Stock 143-V-01 Vegetable Juice Concentrate 06-V-164 – no celery Vegetable Glace –06-V-086 – no celery Vegetable Stock – Low Salt 109-V-01 LAMB STOCK Lamb Stock 06-L-017 Lamb stock with yeast extract, lamb powder and salt Lamb Stock 105-L-11 Lamb stock with added lamb fat, carrot, salt & onion Lamb Glace 109-L-05 PORK STOCK Pork Stock 75-P-026 Pork stock with onion, salt & sage Pork Stock – Low Salt 75-P-054 Smoked Pork Stock 34-P-001 OTHER MEAT STOCKS Turkey Stock 133-T-06 Ham Bouillon 34-NHB-16 Duck Stock 75-D-021 FISH STOCK Fish Stock 75-F-011 Lobster Stock 75-LOB-23 Fish & Shellfish Bouillon 06-F-004 Fish Stock 15-F-004 MUSHROOM STOCK Mushroom Stock 109-MU-6 Wild Mushroom Flavoured Stock 04-MU-02 Porcini Mushroom Stock 22-MU-37 ONION STOCK Onion Stock 06-O-016 Onion Glace 109-O-04 Roast Onion Stock 28-O-001 CHEESE STOCK Cheese Stock 75-CH-08 Mature Cheddar Stock 75-CH-20 Hard Italian Style Cheese Stock 75-PCH-4 Danish Blue style Cheese Stock 75-BLC-40 Nacho Cheese Stock 75-NAC-23 -

Spiced and Pickled Seafoods

Spiced and Pickled Seafoods Pickling with vinegar and spices is an ancient and easy method of preserving seafood. Commercial processors pickle only a few seafood species, but you can pickle almost any seafood at home. Store pickled seafood in the refrigerator at 32-38°F. Use pickled seafoods within 4-6 weeks for best flavor. Refrigerate seafood during all stages of the pickling process. Ingredients and Equipment Use high-quality seafood. Avoid hard water, especially water high in iron, calcium or magnesium. Hard water can cause off-colors and flavors. Use distilled white vinegar containing at least 4½% acetic acid (45 grains) to inhibit bacterial growth. Pure granulated salt (sack salt) is best for pickling, but you can use table salt. Salt high in calcium and magnesium can cause off-colors and flavors. Suitable containers for pickling seafood include large crocks or heavy glass, enamel or plastic containers. Metal containers may cause discoloration of the pickled seafood. Pack pickled seafood in clean glass jars after the pickling process is complete. Cover the seafood with pickling sauce and close the jar lids tightly. Herring Clean herring thoroughly, cut off head, and trim off belly-flesh to the vent. Wash fish, drain, and pack loosely in a large container. Prepare a brine from 2 cups salt, 2 pints vinegar, and 2 pints water. Cover the fish with brine and store in the refrigerator. Leave the fish in the brine until the salt has "struck through," but before the skin starts to wrinkle or lose color. The length of the cure depends upon your judgment, and varies with the temperature, freshness and size of the fish. -

WHAT's COOKING? Roberta Ann Muir Dissertation Submitted In

TITLE PAGE WHAT’S COOKING? Roberta Ann Muir Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the coursework requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Gastronomy) School of History and Politics University of Adelaide September 2003 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE.......................................................................................................................................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS....................................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF TABLES................................................................................................................................................ iv ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................... v DECLARATION................................................................................................................................................... vi 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................1 2 ‘COOKING’ IN OTHER LANGUAGES.......................................................................................................3 2.1 Japanese............................................................................................................................................3 2.2 Tagalog ..............................................................................................................................................4 -

Useandcare&' Cookin~ Guid&;

UseandCare&’ Cookin~ Guid&; Countertop Microwave Oven Contents Adapter Plugs 32 Hold Time 8 Add 30 Seconds 9 Important Phone Numbers 35 Appliance Registration 2 Instigation 32 Auto Defrost 14, 15 Light Bulb Replacement 31 Auto Roast 12, 13 Microwaving Tips 3 Auto Simmer 13 Minute/Second Timer 8 Care and Cleaning 31 Model and Serial Numbers 2,6 Consumer Services 35 Popcorn 16 Control Panel 6,7 Power Levels 8-10 Cooking by Time 9 Precautions 2 Cooking Complete Reminder 6 Problem Solver 33 Cooking Guide 23-29 ProWarn Cooking 5,7 Defrosting by Time 10 Quick Reheat 16 Detiosting Guide 21,22 Safety Instructions 3-5 Delayed Cooting Temperature Cook 11 Double Duty Shelf 5,6,17,30, 3? Temperature Probe 4,6, 11–13, 31 Express Cook Feature 9 WaKdnty Back Cover Extension Cords 32 Features 6 CooHng Gtide 23-29 Glossary of Microwave Terms 17 Grounding Instructions 32 GE Answer Center@ Heating or Reheating Guide 19,20 800.626.2000 ModelJE1456L Microwave power output of this oven is 900 watts. IEC-705 Test Procedure GE Appliances Help us help you... Before using your oven, This appliance must be registered. NEXT, if you are still not pleased, read this book carefully. Please be certtin that it is. write all the details—including your phone number—to: It is intended to help you operate Write to: and maintain your new microwave GE Appliances Manager, Consumer Relations oven properly. Range Product Service GE Appliances Appliance Park Appliance Park Keep it handy for answers to your Louisville, KY 40225 questions. Louisville, KY 40225 FINALLY, if your problem is still If you don’t understand something If you received a not resolved, write: or need more help, write (include your phone number): damaged oven.. -

Steel Pickling: a Profile

December 1993 Steel Pickling: A Profile Draft Report Prepared for John Robson U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Cost and Economic Impact Section Research Triangle Park, NC 27711 EPA Contract Number 68-D1-0143 RTI Project Number 35U-5681-58 DR EPA Contract Number RTI Project Number 68-D1-0143 35U-5681-58 DR Steel Pickling: A Profile Draft Report December 1993 Prepared for John Robson U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Cost and Economic Impact Section Research Triangle Park, NC 27711 Prepared by Tyler J. Fox Craig D. Randall David H. Gross Center for Economics Research Research Triangle Institute Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page 1 Introduction .................. 1-1 2 The Supply Side of the Industry ......... 2-1 2.1 Steel Production .............. 2-1 2.2 Steel Pickling .............. 2-3 2.2.1 Hydrochloric Acid Pickling ..... 2-5 2.2.1.1 Continuous Pickling .... 2-8 2.2.1.1.1 Coils ...... 2-8 2.2.1.1.2 Tube, Rod, and Wire ...... 2-9 2.2.1.2 Push-Pull Pickling ..... 2-10 2.2.1.3 Batch Pickling ....... 2-11 2.2.1.4 Emissions from Steel Pickling 2-11 2.2.2 Acid Regeneration of Waste Pickle Liquor .............. 2-12 2.2.2.1 Spray Roaster Regeneration Process .......... 2-13 2.3 Types of Steel .............. 2-14 2.3.1 Carbon Steels ............ 2-15 2.3.2 Alloy Steels ............ 2-15 2.3.3 Stainless Steels .......... 2-15 2.4 Costs of Production ........... -

Lana Turner Journal

LanaTurner No. 11. Art by Ashwini Bhat, Judith Belzer, BrianShields... LANA TURNER a journal of poetry & opinion #11 by Alain Badiou, Joyelle McSweeney, Essays Display until February Amge Mlinko, Andrew Joron, Farid Matuk... 24, 2018 Poetry by Jorie Graham,Rae Armantrout, Reina Mariía Rodríguez, Aditi Machado, Jacek Guturow... 1 2 Lana Turner a journal of poetry & opinion, no. 11 editors: calvin bedient & david lau Lana Turner: a Journal of Poetry & Opinion is published annually, usually in early November. Price, US $15. To purchase number 11 and see other options, please visit our website, LanaTurnerJournal.com. We accept electronic submissions only; send to [email protected], and only during the months of January, February, and March. We prefer poems in one attachment, with the author’s name at the beginning of the title. No PDF’s, please, unless accompanied by a Word document. Newsstand & select bookstore distribution through Disticor Magazine Distribution Service (disticor.com). Please ask your favorite independent bookstore to order the magazine. Lana Turner™ is a trademark of The Lana Turner Trust, licensed by CMG Worldwide: www.CMGWorldwide.com. Our thanks to David Cormier for the pre-flight wrap-up. Kelley Lehr read copy. ISSN 1949 212X 1 Contents Number eleven 1. Poems Introduction: Writing the Between (6) Aditi Machado, 11 Mary Cisper, 68 Andrew Zawacki, 17 Paul Eluard (Carlos Lara, translator), 72 Jamie Green, 21 Karleigh Frisbie, 77 Douglas Kearney, 26 Michael Farrell, 82 Susan McCabe, 31 C L Young, 85 Mars Tekosky, 34 Felicia Zamora, 90 Kevin Holden, 40 Peter Eirich, 94 Mark Anthony Cayanan, 47 Jonathan Stout, 96 Mark Francis Johnson, 53 Engram Wilkinson, 98 Jacek Gutorow (Piotr Florczyk, Joseph Noble, 100 translator), 60 2. -

Starters Mains Desserts

STARTERS 2 COURSES £25.95 | 3 COURSES £29.95 SEASONAL SOUP OF THE DAY(V) soft bread roll, house churned butter CORNFED CHICKEN, SOFT HERB & PINK PEPPERCORN TERRINE beer pickled shallots, toast SMOKED HAM CROQUETTE house piccalilli, mustard pickle aioli BEETROOT BARLEY RISOTTO(V) black pepper goats cheese balls, spelt granola MAINS BUTTER BRAISED CAULIFLOWER STEAK(VE) romesco sauce, cherry tomato salad, gremolata BREAST OF CORN-FED CHICKEN isle of mull & anchovy emulsion, grilled gem, pancetta crumb 6OZ STEAK BURGER bacon jam, monteray jack, tomato, lettuce on a brioche bun, with fries BRAISED BLACK FACE LAMB PIE potato and black pudding terrine & lamb jus FISH & CHIPS tarragon aioli, tartare sauce 8OZ 50 DAY AGED BEEF RIBEYE (£8 SUPPLEMENT) fries, grilled plum tomato & flat cap mushroom DESSERTS TONKA BEAN CRÈME BRÛLÉE almond biscuits STICKY DATE & GINGER PUDDING toffee sauce, vanilla ice cream PEACH & RASPBERRY PAVLOVA(GF) raspberry sorbet SELECTION OF ARRAN DAIRY ICE CREAMS(GF) CHEFS SELECTION OF SCOTTISH CHEESES & CONDIMENTS (£3 SUPPLEMENT) (V) Vegetarian (VE) Vegan (GF) Gluten Free A number of our dishes can be adapted to cater for your food allergies and deitary requirements. Market Menu Market Please speak to your server who will be able to advise. Full allergy information for each dish is available upon request. w STARTERS MAINS SEASONAL SOUP BUTTER POACHED OF THE DAY (V) LOIN OF PORK served with soft bread roll, house WITH PORK churned butter & SHRIMP FAGGOT £5.50 with black pudding & potato terrine, apple & herb relish, celeriac -

Preservatives” in Today’S Modern Food Industry

A STUDY ON GENERAL OVERWIEW ON “PRESERVATIVES” IN TODAY’S MODERN FOOD INDUSTRY DR. DEIVASIGAMANI REVATHI DR. D. PADMAVATHI HoD / Asst. Professor Guest Professor, P.G. Department of Foods & Nutrition P.G. Department of Foods & Nutrition Muthurangam Govt. Arts College (A), Muthurngam Govt. Arts College (A), Vellore. (TN) INDIA Vellore. (TN) INDIA Food is a perishable commodity. It is affected by a range of physical, chemical and biological processes and under certain conditions it may deteriorate. Besides spoiling many desirable properties of foods, deterioration, together with the growth of microorganisms, may produce toxic substances which have harmful effects on the health of consumers. Through inhibiting the growth of harmful microorganisms and preventing spoilage, food preservatives and antioxidants improve the safety and palatability of foods Over the past two decades, food preservatives and antioxidants played more important roles in food processing due to the increased production of prepared, processed, and convenience foods. Preservatives and antioxidants are required to prolong the shelf-life of many foods. To protect public health, food preservatives and antioxidants have to undergo stringent evaluation by international authorities. In general, preservatives and antioxidants are permitted for food use only when they are proved to present no hazard to the health at the level of use proposed and a reasonable technological need can be demonstrated and the purpose cannot be achieved by other means which are economically and technologically practicable. Furthermore, their uses should not mislead the consumer. So, the present article discusses the need and importance of preservatives in today’s modern food industry. Keywords: Food, Preservatives, Spoilage, Antioxidants, Food Safety, Food Industry. -

The Modern Food Dictionary

THE MODERN FOOD DICTIONARY INGREDIENTS Definitions and many substitutions for unfamiliar THE ingredients. MODERN COOKING TERMS FOOD Do you know what the word flameproof refers to, or frenched? DICTIONARY The answers are in these pages. What’s acidulated water? What’s the difference between parboiling and blanching? What’s sansho? In this EQUIPMENT booklet are definitions for You’ll find clear descriptions some essential cooking terms that of equipment, from a bain-marie will smooth your way in the to an immersion blender. kitchen—keep it close at hand. Consider this your cooking tip sheet and food dictionary in one. TECHNIQUES What’s the difference between braising and steeping? You’ll learn the whys and hows for all kinds of cooking methods here. A B C a b Achiote [ah-chee-OH-tay] The Bain-marie [Banh- slightly musky-flavored, rusty MARIE], or water bath red seed of the annatto tree, A container, usually a roasting available whole or ground. In pan or deep baking dish, that its paste and powder form, it is is partially filled with water. called annatto and is used in Delicate foods, like custards, recipes to add an orange color. are placed in the water bath in their baking dishes during Acidulated water Water to cooking; the surrounding which a mild acid, like lemon water cushions them from the juice or vinegar, has been oven’s heat. added. Foods are immersed in it to prevent them from turning Baking stone or pizza brown. To make acidulated stone A tempered ceramic Artisanal water, squeeze half a lemon slab the size of a baking sheet into a medium bowl of water. -

Parboiling of Paddy Rice, the Science and Perceptions of It As Practiced in Northern Ghana

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 2, ISSUE 4, APRIL 2013 ISSN 2277-8616 Parboiling Of Paddy Rice, The Science And Perceptions Of It As Practiced In Northern Ghana Ayamdoo J. A, Demuyakor B, Dogbe W, Owusu R. Abstract: - Parboiling is a set of operations needed for the production of a gelatinized product. Scientifically it is a thermal treatment process done on rice and other cereals. Water and heat are two essential elements to transform the natural cereal into “parboiled” cereal. In rice, it is done to produce gelatinized or parboiled rice. Parboiling, if examined carefully has other scientific benefits beyond easy milling and reducing broken grains. Unfortunately, the technology has received little attention in terms of research as far as food processing or preservation is concern. As part of an ongoing research to assess the extent to which parboiling affect the migration of vitamin B1, a preliminary survey was conducted between October, 2012 and December, 2012 in the three northern regions of Ghana to elucidate the scientific principles behind the practice and to what extend processors understand these principles. This work also aimed at high lighting the practice so as to encourage people to adapt indigenous technologies which may have more beneficial health effects. Eighty (80) processors in the three northern regions drawn by purposive sampling methods were interviewed using structured and semi structured questionnaires. The results showed that 100% of the people engaged in parboiling business are women with over 70% of them having no formal education and therefore are unaware of any effects of parboiling on nutritional elements. -

·- -Pressure Pa ~Boiling

STUDIES ON METfiODS OF PA~HOILJ ~G . ·~. •, ,~' "< ·- -PRESSURE PA ~BOILIN G. , '' i N.G;C. lENGAR, R: BHASKAR, P. DHARMARA JAN,*,• ABSTRACT .. ··;·, ,f~ . " ' 't~ A meth od of quick parboiling pf paddy has .been worked out using high pre- · ., ,ssure steam wh ich reduces the soaktng and parboiling to 1.5 hrs per batch. The process is cheap in comparison with the methods of parboilmg being carried out _;;. in this country. The method is very suita]Jle for small units located in rural areas, .. -'particularly when combined wi th boilers fired by paddy hu3k, for producing steam and power for parboiling·and drying. ·By this method, breakage of the kernels is ,,, reduced considerably. The mill eut·turn capacity of this method of parboiling is very high and ·a product with a high consumer appeal can be turned out. · Introduction ' ~ .,. ' ·.... At present a large prorortion of rice consumed in India is p1rboiled. Various methods of parboiling are used. In the household method the washed paddy is placed in an open vessel and covered with cold water to a level of 50 mm above the surface of the paddy and heated gently to simmering temperatures just below boiling point of water. This " temperature is maintained overnight. After this, the water is drained off and paddy is steamed until steam emerges at the top. Steaming is done for 5 minutes. The steamed paddy is dried under sun. The product is uniformally soaked and- well parboiled without any off odour, and has an attractive colour. In the commercially adopted, "traditional method", as followed in South !nd!a,_open_air soaking tanks pf larga capacity are used. -

Soldering and Brazing of Copper and Copper Alloys Contents

Soldering and brazing of copper and copper alloys Contents 1. Introduction 4 5. Quality assurance 47 2. Material engineering fundamentals 9 6. Case studies 48 2.1. Fundamentals of copper and copper alloys 9 6.1 Hot-air solder levelling of printed circuit boards 48 2.2 Filler materials 10 6.2 Strip tinning 49 2.2.1 Soft solder 11 6.3 Fabricating heat exchangers from copper 49 2.2.2 Brazing filler metals 13 6.4 Manufacture of compact high-performance 2.3 Soldering or brazing pure copper 16 radiators from copper 49 2.4 Soldering / brazing copper alloys 18 2.4.1 Low-alloyed copper alloys 18 7. Terminology 50 2.4.2. High-alloyed copper alloys 22 8. Appendix 51 3. Design suitability for soldering/brazing 26 References 57 4. Soldering and brazing methods 29 Index of figures 58 4.1 The soldering/brazing principle 29 4.2 Surface preparation 30 Index of tables 59 4.3 Surface activation 32 4.3.1 Fluxes 33 4.3.2 Protective atmosphere / Shielding gases 35 4.4 Applying the solder or brazing filler metal 36 4.5. Soldering and brazing techniques 37 4.5.1 Soldering with soldering iron 38 4.5.2 Dip bath soldering or brazing 38 4.5.3 Flame soldering or brazing 40 4.5.4 Furnace soldering or brazing 40 4.5.5 Electric resistance soldering or brazing 43 4.5.6 Induction soldering or brazing 44 4.5.7 Electron beam brazing 45 4.5.8 Arc brazing 45 4.5.9 Laser beam soldering or brazing 46 2 | KUPFERINSTITUT.DE List of abbreviations Abbreviations Nd:YAG laser Neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser SMD Surface-mounted device PVD Physical vapour deposition RoHS