The Internet Belongs to Everyone by Eric Lee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Check Detailed Interview In

Interviewee: Shigeki Goto Interviewer: Fan Yuanyuan Date: April 13th, 2018 Location: Cyberlabs, Beijing Transcriber: Hong Wei 1:34 FYY: Ok, so let's begin. But today is thirteenth of April, 2018.We’re in office of cyber labs in Beijing and we feel so honored to be able to interview doctor Shigeki Goto here? Am pronouncing it right? (Yes). I’ll briefly introduce the history of Internet project to you. The project is launched in …… It's launched in 2007 to celebrate the first fifty years of the Internet by recording and preserving the personal narratives of global Internet pioneers, uh, their extraordinary contributions to the Internet development. And by 2018, we should have interviewed 500 Internet pioneers, as we planned, and by now is interviewed more than 170 pioneers around the world and about 80 are from overseas of China, and let’s start from the very beginning of you like, uh, your name, where and when were you born and what did your parents do, when you were young? SG: I was born in Utsunomiya city that is near Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture in Japan. Both of my parents basically were school teachers and my father spent most of his life at the unified school district. He was a school teacher. He worked for the administrative structure of the school system. It covers from elementary school, middle school, and high school if they are public. FYY: So that's a big school covered all three… SG: Yes. All the regional public schools are under control of the unified school district. -

The Internet and Isi: Four Decades of Innovation

THE INTERNET AND ISI: FOUR DECADES OF INNOVATION ROD BECKSTROM President and Chief Executive Officer Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) 40th Anniversary of USC Information Sciences Institute 26 April 2012 As prepared for delivery It’s an honor to be here today to mark the 40th anniversary of the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute. Thank you to Herb Schorr for inviting me to speak with you today and participate in the day’s events. When he steps down he will leave some very large shoes to fill. When I received Herb’s invitation, I seized upon it as an opportunity to come before you to express the sincere gratitude that my colleagues and I feel for the work and support of ISI. When I think of ICANN and its development, and all we have accomplished, I never forget that we stand upon the shoulders of giants, many of whom contributed to my remarks today. In fact, I owe a special debt of gratitude to Bob Kahn, who has been a mentor to me. I am honored that he took the time to walk through a number of details in the history I have been asked to relate. The organizers asked me to speak about the history of ISI and ICANN. They also invited me to talk a bit about the future of the Internet. In my role as President and CEO of ICANN, I have many speaking engagements that are forward looking. They are opportunities to talk about ICANN’s work and how it will usher in the next phase in the history of the global, unified Internet that many of you have helped to create. -

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet

The People Who Invented the Internet Source: Wikipedia's History of the Internet PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 22 Sep 2012 02:49:54 UTC Contents Articles History of the Internet 1 Barry Appelman 26 Paul Baran 28 Vint Cerf 33 Danny Cohen (engineer) 41 David D. Clark 44 Steve Crocker 45 Donald Davies 47 Douglas Engelbart 49 Charles M. Herzfeld 56 Internet Engineering Task Force 58 Bob Kahn 61 Peter T. Kirstein 65 Leonard Kleinrock 66 John Klensin 70 J. C. R. Licklider 71 Jon Postel 77 Louis Pouzin 80 Lawrence Roberts (scientist) 81 John Romkey 84 Ivan Sutherland 85 Robert Taylor (computer scientist) 89 Ray Tomlinson 92 Oleg Vishnepolsky 94 Phil Zimmermann 96 References Article Sources and Contributors 99 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 102 Article Licenses License 103 History of the Internet 1 History of the Internet The history of the Internet began with the development of electronic computers in the 1950s. This began with point-to-point communication between mainframe computers and terminals, expanded to point-to-point connections between computers and then early research into packet switching. Packet switched networks such as ARPANET, Mark I at NPL in the UK, CYCLADES, Merit Network, Tymnet, and Telenet, were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s using a variety of protocols. The ARPANET in particular led to the development of protocols for internetworking, where multiple separate networks could be joined together into a network of networks. In 1982 the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP) was standardized and the concept of a world-wide network of fully interconnected TCP/IP networks called the Internet was introduced. -

(Jake) Feinler

Oral History of Elizabeth (Jake) Feinler Interviewed by: Marc Weber Recorded: September 10, 2009 Mountain View, California Editor’s note: Material in [square brackets] has been added by Jake Feinler CHM Reference number: X5378.2009 © 2009 Computer History Museum Oral History of Elizabeth (Jake) Feinler Marc Weber: I’m Marc Weber from the Computer History Museum, and I’m here today, September 10th, 2009, with “Jake” Elizabeth Feinler, who was the director of the Network Information Systems Center at SRI. [This group provided the Network Information Center (NIC) for the Arpanet and the Defense Data Network (DDN), a project for which she was the principal investigator from 1973 until 1991. Earlier she was a member of Douglas Engelbart’s Augmentation Research Center (ARC) at SRI [which [housed] the second computer on the Arpanet. It was on this computer that the NIC resided initially.] Jake is also a volunteer here at the museum. [She has donated an extensive collection of early Internet papers to the museum, and has been working on organizing this collection for some time.] Thank you for joining us. Elizabeth (Jake) Feinler: My pleasure. Weber: I really just wanted to start with where did you grow up and what got you interested in technical things or things related to this. Feinler: [Originally I hoped to pursue a career in advertising design, but could not afford the freshman room and board away from home, so I began attending West Liberty State College (now West Liberty University) close to my home. West Liberty was very small then, and the] art department [wasn’t very good. -

Internet Hall of Fame Announces 2013 Inductees

Internet Hall of Fame Announces 2013 Inductees Influential engineers, activists, and entrepreneurs changed history through their vision and determination Ceremony to be held 3 August in Berlin, Germany [Washington, D.C. and Geneva, Switzerland -- 26 June 2013] The Internet Society today announced the names of the 32 individuals who have been selected for induction into the Internet Hall of Fame. Honored for their groundbreaking contributions to the global Internet, this year’s inductees comprise some of the world’s most influential engineers, activists, innovators, and entrepreneurs. The Internet Hall of Fame celebrates Internet visionaries, innovators, and leaders from around the world who believed in the design and potential of an open Internet and, through their work, helped change the way we live and work today. The 2013 Internet Hall of Fame inductees are: Pioneers Circle – Recognizing individuals who were instrumental in the early design and development of the Internet: David Clark, David Farber, Howard Frank, Kanchana Kanchanasut, J.C.R. Licklider (posthumous), Bob Metcalfe, Jun Murai, Kees Neggers, Nii Narku Quaynor, Glenn Ricart, Robert Taylor, Stephen Wolff, Werner Zorn Innovators – Recognizing individuals who made outstanding technological, commercial, or policy advances and helped to expand the Internet’s reach: Marc Andreessen, John Perry Barlow, Anne-Marie Eklund Löwinder, François Flückiger, Stephen Kent, Henning Schulzrinne, Richard Stallman, Aaron Swartz (posthumous), Jimmy Wales Global Connectors – Recognizing individuals from around the world who have made significant contributions to the global growth and use of the Internet: Karen Banks, Gihan Dias, Anriette Esterhuysen, Steven Goldstein, Teus Hagen, Ida Holz, Qiheng Hu, Haruhisa Ishida (posthumous), Barry Leiner (posthumous), George Sadowsky “This year’s inductees represent a group of people as diverse and dynamic as the Internet itself,” noted Internet Society President and CEO Lynn St. -

Securing the Border Gateway Protocol by Stephen T

September 2003 Volume 6, Number 3 A Quarterly Technical Publication for From The Editor Internet and Intranet Professionals In This Issue The task of adding security to Internet protocols and applications is a large and complex one. From a user’s point of view, the security- enhanced version of any given component should behave just like the From the Editor .......................1 old version, just be “better and more secure.” In some cases this is simple. Many of us now use a Secure Shell Protocol (SSH) client in place of Telnet, and shop online using the secure version of HTTP. But Securing BGP: S-BGP...............2 there is still work to be done to ensure that all of our protocols and associated applications provide security. In this issue we will look at Securing BGP: soBGP ............15 routing, specifically the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) and efforts that are underway to provide security for this critical component of the Internet infrastructure. As is often the case with emerging Internet Virus Trends ..........................23 technologies, there exists more than one proposed solution for securing BGP. Two solutions, S-BGP and soBGP, are described by Steve Kent and Russ White, respectively. IPv6 Behind the Wall .............34 The Internet gets attacked by various forms of viruses and worms with Call for Papers .......................40 some regularity. Some of these attacks have been quite sophisticated and have caused a great deal of nuisance in recent months. The effects following the Sobig.F virus are still very much being felt as I write this. Fragments ..............................41 Tom Chen gives us an overview of the trends surrounding viruses and worms. -

Steve Crocker Resume

STEPHEN D. CROCKER 5110 Edgemoor Lane Bethesda, MD 20814 Mobile: (301) 526-4569 [email protected] SUMMARY Over 50 years of experience in the industrial, academic and government environments involving a wide range of computing and network technologies with specialization in networking and security. Strong background in formal methods, including PhD thesis creating a new logic for reasoning about the correct operation of machine language programs and the development of a program verification system to demonstrate the method. Managed numerous innovative research and development efforts benefiting private industry and government interests. Extensive involvement in the development of the Internet, including development of the initial suite of protocols for the Arpanet, the creation of the RFC series of documents, and multiple involvements in the IETF, ISOC and ICANN organizations. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE BBQ Group 2018-present Founder, leader Development of framework and model for expressing possible, desired and existing registration data directory services policies governing collection, labeling and responses to authorized requests. Shinkuro, Inc., Bethesda, MD 2002-present Co-founder, Chief Executive Officer Development of information-sharing, collaboration and related tools for peer-to-peer cooperative work and inter-platform information management. Coordination of deployment of the DNS security protocol, DNSSEC, throughout the Internet. Longitude Systems, Inc., Chantilly, VA 1999-2001 Co-founder, Chief Executive Officer Development and sale of infrastructure tools for ISPs. Overall direction and management of the company including P&L responsibility, funding, marketing, and technical direction. Executive DSL, LLC, Bethesda, MD 1999-2001 Founder, Chief Executive Officer Creation and operation of DSL-based ISP using Covad and Bell Atlantic DSL circuits. -

Timeline & History of the Internet in Asia and the Pacific, 1992-2017

The Internet Society's 25th anniversary timeline & history of the Internet in Asia and the Pacific 1992-2017 When countries first had Asia-Pacific Internet Global Internet connection milestones Society milestones (based on establishment milestones date of first commercial Internet service provider) 1st IETF meeting in San Diego, USA (1986) Australia (1989) World Wide Web opened to the public (1991) New Zealand (1989) Linux source code released (1991) Internet Society Established 1992 INET '92 Kobe in Japan Hong Kong Japan Malaysia APNIC, the regional Internet address registry National Center for Supercomputing for the Asia-Pacific, 1993 Applications released Mosaic Web Browser established Bangladesh Indonesia st Republic of Korea 1994 1 Internet Society Chapter Philippines founded in Japan Singapore Brunei Darussalam Nepal Windows 95 launched China Pakistan Fiji Sri Lanka 1995 India Taiwan Thailand Yahoo! launched 1st Asia Pacific Regional Maldives Nokia 9000 Communicator released, the Internet Conference on 1st mobile phone with Internet capabilities Mongolia Operational Technologies 1996 Viet Nam (APRICOT) in Singapore Hotmail and Rocketmail launched Cambodia Lao PDR 1997 Solomon Islands Google launched Nauru Asia Pacific Top Level Samoa 1998 ICANN established Domain Name Association (APTLD) established IPv6 specification released by IETF Bhutan Papua New Guinea 1st Blackberry 1999 device launched Alibaba established 1st IETF meeting in the Asia-Pacific Myanmar SEA-ME-WE3 region in Adelaide, Australia Tuvalu submarine cable 2000 completed Trek -

List of Internet Pioneers

List of Internet pioneers Instead of a single "inventor", the Internet was developed by many people over many years. The following are some Internet pioneers who contributed to its early development. These include early theoretical foundations, specifying original protocols, and expansion beyond a research tool to wide deployment. The pioneers Contents Claude Shannon The pioneers Claude Shannon Claude Shannon (1916–2001) called the "father of modern information Vannevar Bush theory", published "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" in J. C. R. Licklider 1948. His paper gave a formal way of studying communication channels. It established fundamental limits on the efficiency of Paul Baran communication over noisy channels, and presented the challenge of Donald Davies finding families of codes to achieve capacity.[1] Charles M. Herzfeld Bob Taylor Vannevar Bush Larry Roberts Leonard Kleinrock Vannevar Bush (1890–1974) helped to establish a partnership between Bob Kahn U.S. military, university research, and independent think tanks. He was Douglas Engelbart appointed Chairman of the National Defense Research Committee in Elizabeth Feinler 1940 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, appointed Director of the Louis Pouzin Office of Scientific Research and Development in 1941, and from 1946 John Klensin to 1947, he served as chairman of the Joint Research and Development Vint Cerf Board. Out of this would come DARPA, which in turn would lead to the ARPANET Project.[2] His July 1945 Atlantic Monthly article "As We Yogen Dalal May Think" proposed Memex, a theoretical proto-hypertext computer Peter Kirstein system in which an individual compresses and stores all of their books, Steve Crocker records, and communications, which is then mechanized so that it may Jon Postel [3] be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. -

The Amateur Computerist Gathers an Article Was Written and Published in the Some Documents from That Celebration

The Amateur Comp u terist http://www.ais.org/~jrh/acn/ Summer 2008 ‘Across the Great Wall’ Volume 16 No. 2 2007. Participating were international Internet pio- Celebration neers, representatives of the Internet in China and The First Email Message from China to CSNET historians and journalists. From 1983 to 1987, two teams of scientists and engineers worked to overcome the technical, financial, and geographic obstacles to set up an email connection between China and the interna- tional CSNET. One team was centered around Werner Zorn at Karlsruhe University in the Federal Republic of Germany. The other team was under the general guidance of Wang Yuenfung at the In- stitute for Computer Applications (ICA) in the Peo- ple’s Republic of China. The project succeeded based on the scientific and technical skill and friendship, resourcefulness and dedication of the members of both teams. The first successful email message was sent on Sept 20, 1987 from Beijing to computer scien- tists in Germany, the U.S. and Ireland. The China- CSNET connection was granted official recogni- tion and approval on Nov 8 1987 when a letter (Composed 14 Sept 1987, sent 20 Sept 1987) signed by the Director of the U.S. National Science Foundation Division of Networking and Commu- A celebration of the 20th anniversary of the nications Research and Infrastructure Stephen first email message that was sent from China to the Wolff was forwarded to the head of the Chinese world via the international Computer Science Net- delegation, Yang Chuquan at an International work (CSNET) was held at the Hasso Plattner In- Networkshop in the U.S. -

Internet Governance: ! Where Are We Now?

Internet Governance: ! Where Are We Now? Feb 24, 1999 Scott Bradner Harvard University [email protected] gov - 1 Internet Realities ◆ once a toy, now infrastructure ◆ thousands of Internet service providers (ISPs) ◆ hundreds of exchange points between ISPs ◆ little government money some support for basic research, but not operations (US anyway) ◆ no one “runs” it gov - 2 Is anyone in control? ◆ no (well mostly no) no dominant provider trans-border so no single government no useful industry group ◆ standards group “closest thing to governance” ( The Gordian Knot ) Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) but that is not governance! gov - 3 Internet Engineering Task Force - IETF ◆ develops Internet “standards” not “standards” in the ISO / ITU / ANSI sense standards in the ‘lots of people use it’ sense ◆ does little policy technology does dictate some policy - e.g RFC 2050 required good security in IPv6 ◆ international, non-member organization ◆ IETF is the standards creation part of the Internet Society (ISOC) gov - 4 IETF, contd. ◆ now working in the same area as “traditional” standards organizations result of “convergence” everything over IP (the Internet Protocol) competing standards in some cases cooperation in others ◆ technical part of the Internet now runs under IETF rules not all that unhappy to be rid of the responsibility gov - 5 What does governance mean in the Internet context? ◆ governance means answering two questions Who says who makes the rules? Who says who pays for what? ◆ easy in most current technology areas railroad regulations, -

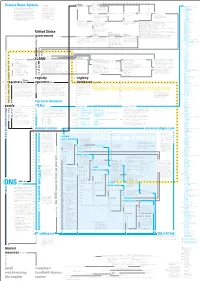

Domain Name System Concept

8 originally chartered standards charters 0 Concept Map organizations include ISoc members form 243 active ccTLDs Domain Name System rely on .ac Ascension Island (licensed) 28 Internet Society (ISoc) is a professional .ad Andorra A concept map is a web of terms. Verbs membership society with more than 150 This diagram is a model of the Domain .ae United Arab Emirates connect nouns to form propositions. organizations and 11,000 individual mem- .af Afghanistan 27 Name System (DNS), a system vital to the Groups of propositions form larger struc- bers from over 182 countries. tures. Examples and details accompany .ag Antigua and Barbuda smooth operation of the Internet. The goal most terms. More important terms re- .ai Anguilla of the diagram is to explain what DNS ceive visual emphasis; less important 11 .al Albania terms, details, and examples are in gray. IETF sponsors working groups are managed by IESG decisions can be appealed to IAB provides advice to IANA functions were moved to .am Armenia is, how it works, and how it’s governed. Terms related to names and addresses write approves .an Netherlands Antilles The diagram knits together many facts (the heart of DNS) are in blue. Terms Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) Internet Engineering Steering Internet Architecture Board (IAB) Internet Assigned Numbers .ao Angola followed by a number link to terms pre- is a voluntary, non-commercial organization Group (IESG) Authority (IANA) originally handled .aq Antarctica about DNS in hopes of presenting a com- ceded by the same number. comprised of individuals concerned with the many of the functions that are now 626,000 .ar Argentina prehensive picture of the system and the evolution of the architecture and operation ICANN’s responsibility.