ABSTRACT ROCK N' ROLL WILL SAVE US by Joseph Daniel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Information Prepared by the Project

Roads of Destiny 1 Roads of Destiny **The Project Gutenberg Etext of Roads of Destiny, by O. Henry** #4 in our series by O Henry Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information about Project Gutenberg 2 Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Roads of Destiny by O. Henry February, 1997 [Etext #1646] **The Project Gutenberg Etext of Roads of Destiny, by O. Henry** ******This file should be named rdstn10.txt or rdstn10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, rdstn11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, rdstn10a.txt. Etext prepared by John Bickers, [email protected] and Dagny, [email protected] We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. The official release date of all Project Gutenberg Etexts is at Midnight, Central Time, of the last day of the stated month. -

Lil Uzi Songs Download

Lil uzi songs download Continue Source:4,source_id:870864.object_type:4, id:870864,status:0,title:LIL U ULTRASOUND VERT,share_url:/artist/lil-uzi-vert,albumartwork: objtype:4 Thank you for showing interest in '. It is only available in India. Click here to go to the homepage or you'll be automatically redirected within 10 seconds. setTimeout (function) $'.'.artistDetailPage.artistAbout'). Download music from your favorite artists for free with Mdundo. Mdundo started in collaboration with some of Africa's best artists. By downloading music from Mdundo YOU to become part of the support of African artists!!! Mdundo is financially supported by 88mph - in partnership with Google for Entrepreneurs. Mdundo kicks the music into the stratosphere, taking the artist's side. Other mobile music services hold 85-90% of sales. What ?!, Yes, most of the money is in the pockets of major telecommunications companies. Mdundo lets you track your fans and we share any revenue earned from the site fairly with the artists. I'm a musician! - Log in or sign up for hip-hop August 2, 202015 September 2020 Olami Published in Hip Hop, TrendingTagged Future, Lil Uzi Vert1 Best Rap Song 2019Featuring Lil Uzi Vert, Doja Cat, and Young Thug, along with many exciting young upstarts 20 Best Rap Albums 2017 From Playboi Carti's muttering opus Vince Staples' delirium up deconstructed fame, is the most important rap record of the year. The 100 best songs of 2017 from Lord's ecstatic emotional purification to Frank Ocean's ode to cycling to the frantic knock of Cardi B, this is our pick for the best songs of the year. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JUNE 18, 2007 No. 98 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was mismanagement, corruption, and a per- In this program, people receive an called to order by the Speaker pro tem- petual dependence upon foreign aid and overnight transfer from an American pore (Ms. HIRONO). remittances. Mexico must make tough bank account to a Mexican one. The f decisions and get its economy in shape. two central banks act as middlemen, Until then, Madam Speaker, we will taking a cut of about 67 cents no mat- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO continue to face massive immigration ter what the size of the transaction. TEMPORE from the south. According to Elizabeth McQuerry of The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- While we are painfully aware of the the Federal Reserve, banks then typi- fore the House the following commu- problems illegal immigration is caus- cally charge $2.50 to $5 to transfer ing our society, consider what it is nication from the Speaker: about $350. In total, this new program doing to Mexico in the long run. The WASHINGTON, DC, cuts the costs of remittances by at June 18, 2007. massive immigration is draining many least half. In America, 200 banks are I hereby appoint the Honorable MAZIE K. villages across Mexico of their impor- now signed up for this service com- HIRONO to act as Speaker pro tempore on tant labor pool. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

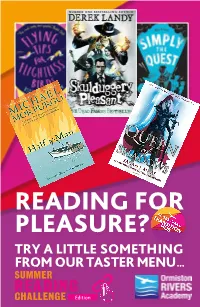

Reading for Pleasure? Try a Little Something from Our Taster Menu

READING FOR PLEASURE? TRY A LITTLE SOMETHING FROM OUR TASTER MENU... Edition Looking for something to read but don’t know where to begin? Dip into these pages and see if something doesn’t strike a spark. With over thirty titles (many of which come recommended by the organisers of World Book Day - including a number of best sellers), there is bound to be something to appeal to every taste. There is a handy, interactive contents page to help you navigate to any title that takes your fancy. Feeling adventurous? Take a lucky dip and see what gems you find. Cant find anything here? Any Google search for book extracts will provide lots of useful websites. This is a good one for starters: https://www. penguinrandomhouse.ca/books If you find a book you like, there are plenty of ways to access the full novel. Try some of the services listed below: Chargeable services Amazon Kindle is the obvious choice if you want to purchase a book for keeps. You can get the app for both Apple and Android phones and will be able to buy and download any book you find here. If you would rather rent your books, library style, SCRIBD is the best app to use. They charge £8.99 per month but you can get the first 30 days free and cancel at any time. If you fancy listening to your favourite stories being read to you by talented voice recording artists and actors, tryAudible : they offer both one off purchases and subscription packages. Free services ORA provides access to myON and you will have already been given details for how to log in. -

Free Mp3 Download Godsmack Bulletproof What Movie Is the Song Bulletproof by Godsmack On

free mp3 download godsmack bulletproof what movie is the song bulletproof by godsmack on. The reign continues for Godsmack 39s 39Bulletproof 39 which enjoys a fourth week atop the Mediabase active rock radio chart. 39Bulletproof 39 received 1997 spins during the June 1723 tracking period . Licensing information for Bulletproof by Godsmack. Master Use License This gives you the right to use the song for TV film commercials and other audiovideo projects. Synchronization License Also called a 34Sync Licence 34 this gives you the right to edit the song into a production of some kind thus 34synching 34 it to the video. You would need this for a commercial or music video for example . Godsmack Bulletproof Lyrics MetroLyrics. Lyrics to 39Bulletproof 39 by Godsmack. Contemplating Isolating and it 39s stressing me out Different visions contradictions why won 39t you let me out I need a way to separate it. GO K WHEN LEGENDS RISE LYRICS. Legs are tied these hands are brokenltbrgtAlone I try with words unspokenltbrgtSilent cry my breath is frozenltbrgtWith blinded eyes I fear myself ltbrgtIt 39s burning down it 39s burning highltbrgtWhen ashes fall the legends riseltbrgtWe burned it out oh my oh whyltbrgtWhen ashes fall the legends riseltbrgtMy . Bulletproof MP3 and Music Downloads at Juno Download. Review Bulletproof present a brand new artist Cannon. Little is known about him at this juncture but the music does more than enough representing as he fires off shots in all directions. 34Turn Around 34 is a grizzly scud with rising chords and a high voltage bassline buzzing and zipping around ferociously underneath. -

Sloan Parallel Play Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sloan Parallel Play mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Parallel Play Country: Canada Released: 2008 MP3 version RAR size: 1959 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1842 mb WMA version RAR size: 1607 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 435 Other Formats: WMA VOX MOD VQF MMF XM APE Tracklist 1 Believe In Me 3:18 2 Cheap Champagne 2:46 3 All I Am Is All You're Not 3:03 4 Emergency 911 1:50 5 Burn For It 2:38 6 Witch's Wand 2:50 7 The Dogs 3:54 8 Living The Dream 2:53 9 The Other Side 2:54 10 Down In The Basement 2:59 11 If I Could Change Your Mind 2:08 12 I'm Not A Kid Anymore 2:26 13 Too Many 3:43 Credits Mastered By – Joao Carvalho Mixed By – Nick Detoro, Sloan Performer – Andrew Scott , Chris Murphy , Jay Ferguson , Patrick Pentland Performer [Additional] – Dick Pentland, Gregory Macdonald, Kevin Hilliard, Nick Detoro Producer – Nick Detoro, Sloan Recorded By – Nick Detoro Written-By – Sloan Notes The packaging is a four panel digipak. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 6 6674-400047 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year YEP 2180 Sloan Parallel Play (CD, Album) Yep Roc Records YEP 2180 US 2008 Bittersweet Recordings, BS 055 CD Sloan Parallel Play (CD, Album) BS 055 CD Spain 2008 Murderecords Parallel Play (LP, Album, Yep-2180 Sloan Yep Roc Records Yep-2180 US 2008 180) Parallel Play (CD, Album, YEP-2180 Sloan Yep Roc Records YEP-2180 US 2008 Promo) HSR-002 Sloan Parallel Play (CD, Album) High Spot Records HSR-002 Australia 2008 Related Music albums to Parallel Play by Sloan P.F. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido

DESCUENTOS TIENDAS DE MUSICA 5 Unidades 3% CONSULTAR PRECIOS Y 10 Unidades 5% CONDICIONES DE DISTRIBUCION 20 Unidades 9% e-mail: [email protected] 30 Unidades 12% Tfno: (+34) 982 246 174 40 Unidades 15% LISTADO STOCK, actualizado 09 / 07 / 2021 50 Unidades 18% PRECIOS VALIDOS PARA PEDIDOS RECIBIDOS POR E-MAIL REFERENCIAS DISPONIBLES EN STOCK A FECHA DEL LISTADOPRECIOS CON EL 21% DE IVA YA INCLUÍDO Referencia Sello T Artista - Titulo Estilo PAIS PVP Pedido 3024-DJO1 3024 12" DJOSER - SECRET GREETING EP BASS NLD 14.20 AAL012 9300 12" EMOTIVE RESPONSE - EMOTIONS '96 TRANCE BEL 15.60 0011A 00A (USER) 12" UNKNOWN - UNTITLED TECHNO GBR 9.70 MICOL DANIELI - COLLUSION (BLACKSTEROID 030005V 030 12" TECHNO ITA 10.40 & GIORGIO GIGLI RMXS) SHINEDOE - SOUND TRAVELLING RMX LTD PURE040 100% PURE 10" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.60 (RIPPERTON RMX) BART SKILS & ANTON PIEETE - THE SHINNING PURE043 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 8.90 (REJECTED RMX) DISTRICT ONE AKA BART SKILS & AANTON PURE045 100% PURE 12" T-MINIMAL NLD 9.10 PIEETE - HANDSOME / ONE 2 ONE DJ MADSKILLZ - SAMBA LEGACY / OTHER PURE047 100% PURE 12" TECHNO NLD 9.00 PEOPLE RENATO COHEN - SUDDENLY FUNK (2000 AND PURE088 100% PURE 12" T-HOUSE NLD 9.40 ONE RMX) PURE099 100% PURE 12" JAY LUMEN - LONDON EP TECHNO NLD 10.30 DILO & FRANCO CINELLI - MATAMOSCAS EP 11AM002 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 (KASPER & PAPOL RMX) FUNZION - HELADO EN GLOBOS EP (PAN POT 11AM003 11:00 A.M. 12" T-MINIMAL DEU 9.30 & FUNZION RMXS) 1605 MUSIC VARIOUS ARTISTS - EXIT PEOPLE REMIXES 1605VA002 12" TECHNO SVN 9.30 THERAPY (UMEK, MINIMINDS, DYNO, LOCO & JAM RMXS) E07 1881 REC. -

Lourish a Mosaic of Souls: Happiness and the Self

lourish A Mosaic of Souls: Happiness and the Self Spring 2015 Volume 3, Issue 1 flourish An Undergraduate Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Human Flourishing Founder Daniel First Editor-in-chief Celina Chiodo Design Editor Isaac Morrier Development Coordinators Christina Bradley Abigail Gahm Treasurer Scott Remer Associate Editors Daniel Shkolnik Minh Nguyen Grant Kopplin John O’Malley Board of Advisors Hedy Kober Assistant Professor, Yale Psychiatry Department Joshua Knobe Chair Yale Program in Cognitive Science Laurie Santos Director of Undergraduate Studies, Yale Psychology Department 1 flourish An Undergraduate Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Human Flourishing 2 From the Editor Dear Readers, You will find many facets of happiness in this issue of Flourish. The pieces fit together not so much as a narrative but in mosaic form. Each article offers its own approach to striving for happiness and well-being—through social interaction, through art and play, through compassion, etc. In the last issue, the question of controlling happiness was discussed; in this issue, by striving for happiness, we consider the elements of happiness within our control. The collection of academic articles, op-eds, and personal accounts express a diversity of perspectives so that you, the reader, can explore happiness. This is my first year publishing the journal, and I am in awe of what the writers and staff members have contributed. I have learned so much through the speaker dinner series, the artwork and the articles that can be found on these pages, and I am thrilled to share these perspectives with you. I cannot thoroughly express my gratitude for the editors who exercised patience with me, especially Bo, former editor-in-chief, for helping me through the publi- cation process, and Isaac, our design editor. -

©2007 Melissa Tracey Brown ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

©2007 Melissa Tracey Brown ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ENLISTING MASCULINITY: GENDER AND THE RECRUITMENT OF THE ALL-VOLUNTEER FORCE by MELISSA TRACEY BROWN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Political Science written under the direction of Leela Fernandes and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2007 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Enlisting Masculinity: Gender and the Recruitment of the All-Volunteer Force By MELISSA TRACEY BROWN Dissertation Director: Leela Fernandes This dissertation explores how the US military branches have coped with the problem of recruiting a volunteer force in a period when masculinity, a key ideological underpinning of military service, was widely perceived to be in crisis. The central questions of this dissertation are: when the military appeals to potential recruits, does it present service in masculine terms, and if so, in what forms? How do recruiting materials construct gender as they create ideas about soldiering? Do the four service branches, each with its own history, institutional culture, and specific personnel needs, deploy gender in their recruiting materials in significantly different ways? In order to answer these questions, I collected recruiting advertisements published by the four armed forces in several magazines between 1970 and 2003 and analyzed them using an interpretive textual approach. The print ad sample was supplemented with television commercials, recruiting websites, and media coverage of recruiting. The dissertation finds that the military branches have presented several versions of masculinity, including both transformed models that are gaining dominance in the civilian sector and traditional warrior forms.