Performance-Based Art and the Racialised Body by David a Bailey Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are We There Yet?

ARE WE THERE YET? Study Room Guide on Live Art and Feminism Live Art Development Agency INDEX 1. Introduction 2. Lois interviews Lois 3. Why Bodies? 4. How We Did It 5. Mapping Feminism 6. Resources 7. Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION Welcome to this Study Guide on Live Art and Feminism curated by Lois Weaver in collaboration with PhD candidate Eleanor Roberts and the Live Art Development Agency. Existing both in printed form and as an online resource, this multi-layered, multi-voiced Guide is a key component of LADA’s Restock Rethink Reflect project on Live Art and Feminism. Restock, Rethink, Reflect is an ongoing series of initiatives for, and about, artists who working with issues of identity politics and cultural difference in radical ways, and which aims to map and mark the impact of art to these issues, whilst supporting future generations of artists through specialized professional development, resources, events and publications. Following the first two Restock, Rethink, Reflect projects on Race (2006-08) and Disability (2009- 12), Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three (2013-15) is on Feminism – on the role of performance in feminist histories and the contribution of artists to discourses around contemporary gender politics. Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has involved collaborations with UK and European partners on programming, publishing and archival projects, including a LADA curated programme, Just Like a Woman, for City of Women Festival, Slovenia in 2013, the co-publication of re.act.feminism – a performing archive in 2014, and the Fem Fresh platform for emerging feminist practices with Queen Mary University of London. Central to Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has been a research, dialogue and mapping project led by Lois Weaver and supported by a CreativeWorks grant. -

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

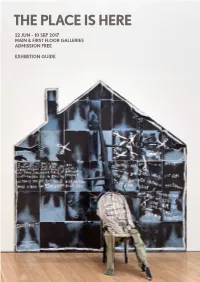

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A Question of the Body and its Reflections as Gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2017 When: Thursday: 6:30 p.m. to 8:20p.m. Where: PCYNH 106 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Thursday. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

Motiroti Brochure

motiroti motiroti /The Builders Association’s Alladeen was presented as a cross media perfomance for stage, music video and a web project. It toured internationally (2002-05) to numerous venues and received an OBIE Award in New York. Photo: Simone Lynn. motiroti is a London based arts organisation within visual and live art, new technology led by artistic director Ali Zaidi. For over ten and socially engaged practice, our projects years the company has made internationally are accessible to a wide audience through acclaimed and award winning art that multiple layers of interpretation. We foster transforms relationships between people, the development of a lifelong learning communities and spaces. motiroti works at culture. Learning and art production are the forefront of ever-changing global social part of the same process, and offer equally realities, challenging and teasing perceptions potent opportunities to inspire and develop of artists, institutions and audiences alike. a dynamic exchange between artists and communities. Working with a range of collaborators HITTUCK motiroti is one of the few arts organisations truly to stretch between W international cutting edge work and the lives of people in their own communities. They gain their inspiration from life in all its rich forms – it shows. If only more arts had this breadth of vision. Jenny Edwards, CEO Homeless Link ANDREW PHOTO: This page, clockwise from top right: Harvest it! (2007). Kakatsitsi Drummers performing at the autumn festival in Myatt’s Fields Park. Harvest it! Vassall Voices Children’s Choir. The Seed The Root GOEBEL (1995). From a series A of images installed HITTUCK in Brick Lane. -

Motion and Time Based: a Question of the Body and Its Reflections As Gesture

Introduction to Art Making- Motion and Time Based: A question of the body and its reflections as gesture. ...material action is painting that has spread beyond the picture surface. The human body, a laid table or a room becomes the picture surface. Time is added to the dimension of the body and space. - "Material Action Manifesto," Otto Muhl, 1964 VIS 2 Winter 2016 When: Tuesday: 5:00 p.m. to 6:50 p.m. Where: CENTR 101 Professor: Ricardo Dominguez Email: [email protected] Office Hour: Mondays. 11:00 a.m. to Noon. Room: VAF Studio 551 (2nd Fl. Visual Art Facility) The body-as-gesture has a long history as a site of aesthetic experimentation and reflection. Art-as-gesture has almost always been anchored to the body, the body in time, the body in space and the leftovers of the body This class will focus on the history of these bodies-as-gestures in performance art. An additional objective for the course will be a focus on the question of documentation in order to understand its relationship to performance as an active frame/framing of reflection. We will look at modernist, contemporary and post-contemporary, contemporary work by Chris Burden, Ulay and Abramovic, Allen Kaprow, Vito Acconci, Coco Fusco, Faith Wilding, Anne Hamilton, William Pope L., Tehching Hsieh, Revered Billy, Nao Bustamante, Ana Mendieta, Cindy Sherman, Adrian Piper, Sophie Calle, Ron Athey, Patty Chang, James Luna, and the work of many other body artists/performance artists. Students will develop 1 performance action a week, for 5 weeks, for a total of 5 gestures/actions (during the first part of the class), individually or in collaboration with other students. -

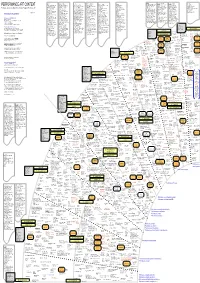

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Spsl / Cv 01 / 2018 1

SPSL / CV www.susanpuisanlok.com 01 / 2018 H: 32 Warren Rd, London E4 6QS | E: [email protected] | M:+44 (0) 7720303268 W: Middlesex University, Grove G226, The Burroughs, London NW4 4BT | E: [email protected] SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 RoCH Fans & Legends CFCCA 30th Anniversary Progamme, Manchester, UK 2015 RoCH Fans & Legends QUAD, Derby, UK 2014 Faster, Higher MAI (Montréal Arts Interculturels), QC, Canada 2012 Faster, Higher The Gallery at Winchester Discovery Centre 2008 Faster, Higher BFI Southbank Gallery, London, UK 2007-2008 DIY Ballroom/Live Bigger Picture/ BBC Screen touring commission Cornerhouse Manchester; enter_, Norwich; Lumen, Leeds; Site Gallery, Sheffield, UK 2006 Golden (Lessons) Beaconsfield, London, UK 2006 Golden Chinese Arts Centre, Manchester, UK 2000 FCHKUK exhibition, Stuff Gallery, London, UK 2000 Lean To exhibition, East London Gallery, University of East London, UK 1996-1997 Un- (retrospectre) exhibition, Chinese Arts Centre, Manchester, UK SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS & SCREENINGS 2018 Presence: A Window on Contemporary Chinese Art St George’s Hall, Liverpool, UK 2018 Diaspora Pavilion Wolverhampton Art Gallery, UK 2017 Diaspora Pavilion Palazzo Pisani a Santa Marina, Venice 2017 Sonic Soundings / Venice Trajectories Venice www.sonicsoundings.com 2015-2016 1st Asia Biennial / 5th Guangzhou Triennial Guangdong Museum of Art, China, UK 2013 The Global Archive Hanmi Gallery, London, UK 2012 Blue Crystal Ball Samsung IOC Media Art Collection, De La Warr Pavilion, UK AND Festival, Manchester, UK 2012 Everything Flows -

Examining the Creative Practices of Kiera Boult, Madelyne Beckles, Kalale Dalton-Lutale and Cason Sharpe

Chosen Family Values: Examining the Creative Practices of Kiera Boult, Madelyne Beckles, Kalale Dalton-Lutale and Cason Sharpe by Delilah Rosier Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design and New Media Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 2021. Delilah Rosier, 2021 2 Abstract This major research paper presents an autoethnographic account of the cultural production: performances, plays, video, poetry, short stories, Instagram takeovers and lived experiences of Black biracial Canadian artists Madelyne Beckles, Kalale Dalton-Lutale, Kiera Boult, and Cason Sharpe. Putting these artists in conversation with one another serves to connect and archive a creative community and moment by way of shared identities, and shared stylistic, generational, and critical vocabularies. The thread that runs throughout their works is a critical framework informed by Black thinkers and perspectives encompassing Black art and artists, feminism, queerness, pop culture, class consciousness, and intersectionality stemming from a distinctly Canadian context. As a commemoration of kinship and as a contribution to the current discourse of contemporary Canadian art, this paper makes a case for how their creative practices speak from and about a unique, intersectional perspective and make a significant contribution to the Canadian art landscape. 3 Acknowledgments Thank you to my advisors Johanna Householder and Andrea Fatona for your rigorous edits and thoughtful commentary, Rebecca Diederichs for guiding my writing spiral, Daniel Payne for your incredible bibliographic assistance, OCAD University and the Ontario Graduate Scholarship for financially supporting my studies, Fraser Wrighte for your continual support and Madelyne, Kiera, Kalale and Cason for your participation and trust in me. -

Sonia Boyce Reader

Sonia Boyce Reader Contents 2 Bio 3 Sonia Boyce - Gathering a History of Black Women 4 The Black British Arts Movement 7-12 Artist Interviews - various sources 13 Recent Work in Pictures 1 Sonia Boyce MBE is a British Afro-Caribbean artist and educator who lives and works in London. She went to art school aged 15, making large pastel drawings and photographic collages, exploring issues of race and gender in the media and everyday life. Since then, her practice has expanded to incorporate a wider variety of media, including performance, film, installation and sound - but her true medium is people. In 2007 Boyce was awarded an MBE for services to the arts, and in 2016 was elected a Royal Academician. Boyce is Professor of Black Art and Design at the University of the Arts London. “In the broadest sense, my research interests lie in art as a social practice and the critical and contextual debates that arise from this burgeoning field. Since the 1990s my own art practice has relied on working with other people in collaborative and participatory situations, often demanding of those collaborators spontaneity and unrehearsed performative actions. Working across media, mainly drawing, print, photography, video and sound, I recoup the remains of these performative gestures – the leftovers, the documentation – to make the art works, which are often concerned with the relationship between sound and memory, the dynamics of space, and incorporating the spectator.” - Sonia Boyce, University of the Arts London At age 23, her 1985 painting Missionary Position II was the first artwork by a black artist 2 acquired by the Tate collection – and only the 5th work by a female artist in the collection. -

Sonia Boyce // Helen Johnson at the ICA 1 February – 2 April 2017 Preview: 31 January 2017

Press Release: November 2016 Sonia Boyce // Helen Johnson at the ICA 1 February – 2 April 2017 Preview: 31 January 2017 The ICA is pleased to announce solo exhibitions by artists Sonia Boyce and Helen Johnson. Sonia Boyce’s We move in her way explores questions around power and play between audience and performer within a live improvisation, then uses the documentation to create a multimedia installation. Helen Johnson: Warm Ties uses painting to highlight the relationship between Britain and colonial Australia. Johnson places the viewer in a space in which to reflect on the mentality of British colonisers on Australia. Both highly acclaimed artists will be exhibiting in the Lower and Upper Galleries, respectively, 1 February – 2 April 2017. Sonia Boyce: We move in her way Upper Gallery IMAGE: Sonia Boyce’s We move in her way. Photographer: George Torode Sonia Boyce’s piece We move in her way involves the exploratory vocal and movement performances of Elaine Mitchener, Barbara Gamper and her dancers : Eve Stainton, Ria Uttridge and Be van Vark, with an invited audience. The title of the work suggests two possible readings: that ‘she’ dictates our movements; or that we obstruct ‘hers’, with both interpretations suggesting power is at play. Boyce has a participatory art practice where she invites others to engage performatively with improvisation. In this process, she encourages contributors to exercise their own responses to the situations she enables, where she steps back from any directorial position to observe the activities and dynamics of exchange as they unfold. Once the performance is played out and documented, Boyce reshapes the material generated, in what she calls “recouping the remains”, to create the artwork as a multimedia installation. -

Black British Art History Some Considerations

New Directions in Black British Art History Some Considerations Eddie Chambers ime was, or at least time might have been, when the writing or assembling of black British art histories was a relatively uncom- Tplicated matter. Historically (and we are now per- haps able to speak of such a thing), the curating or creating of black British art histories were for the most part centered on correcting or addressing the systemic absences of such artists. This making vis- ible of marginalized, excluded, or not widely known histories was what characterized the first substantial attempt at chronicling a black British history: the 1989–90 exhibition The Other Story: Asian, African, and Caribbean Artists in Post-War Britain.1 Given the historical tenuousness of black artists in British art history, this endeavor was a landmark exhibi- tion, conceived and curated by Rasheed Araeen and organized by Hayward Gallery and Southbank Centre, London. Araeen also did pretty much all of the catalogue’s heavy lifting, providing its major chapters. A measure of the importance of The Other Story can be gauged if and when we consider that, Journal of Contemporary African Art • 45 • November 2019 8 • Nka DOI 10.1215/10757163-7916820 © 2019 by Nka Publications Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/nka/article-pdf/2019/45/8/710839/20190008.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Catalogue cover for the exhibition Transforming the Crown: African, Asian, and Caribbean Artists in Britain 1966–1996, presented by the Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute, New York, and shown across three venues between October 14, 1997, and March 15 1998: Studio Museum in Harlem, Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Caribbean Cultural Center African Diaspora Institute.