Robles, E. (2019). Making Waves: 'Black Art' in Britain Before the 1980S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

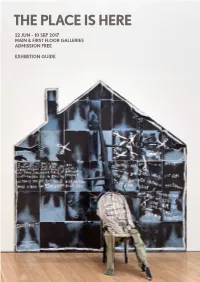

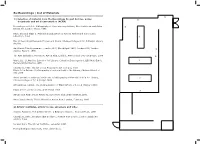

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990

Donald Rodney (1961-1998) Self-Portrait ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ 1990 Medium: Lightboxes with Duratran prints Size: 5 parts, total, 190.5 x 121.9cm Collection: Arts Council ACC7/1990 1. Art historical terms and concepts Subject Matter Traditionally portraits depicted named individuals for purposes of commemoration and/or propaganda. In the past black figures were rarely portrayed in Western art unless within group portraits where they were often used as a visual and social foil to the main subject. Rodney adopted the portrait to explore issues around black masculine identity - in this case the stereotype of young black men as a ‘public enemy’. The title ‘Black Men Public Enemy’ comes from the writings of cultural theorist Stuart Hall about media representations of young black men as an ‘icon of danger’, a metaphor for all the ills of society. Rodney said of this Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 1164651 | www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk work: “I’ve been working for some time on a series…about a black male image, both in the media and black self-perception. I wanted to make a self-portrait [though] I didn’t want to produce a picture with an image of myself in it. It would be far too heroic considering the subject matter. I wanted generic black men, a group of faces that represented in a stereotypical way black man as ‘the other’, a black man as the enemy within the body politic” (1991). Rodney is asking the question: ‘Is this what people see when they see me?’ He has created a kind of ‘everyman’ for every black man, a heterogeneous identity. -

Lubaina Himid OUR KISSES ARE PETALS

Media Release: 5 April 2018 PRESS PREVIEW Thursday 10 May 2018 EXHIBITION 11 May – 30 September 2018 Lubaina Himid OUR KISSES ARE PETALS Lubaina Himid, Why are you Looking, 2018. Image courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art will launch the first in a series of exhibitions for the UK’s largest public event of 2018, the Great Exhibition of the North (22 June – 9 September), with a solo show of new work by Turner Prize-winning artist Lubaina Himid. Our Kisses are Petals will run from 11 May – 30 September, and will feature a community-focussed outdoor commission beginning in June. Our Kisses are Petals originates from new paintings on cloth that employ the patterns, colours and symbolism of the Kanga, a vibrant cotton fabric traditionally worn by East African women as a shawl, head scarf, baby carrier, or wrapped around the waist. Typically, kangas consist of three parts: the pindo (border), the mji (central motif), and the jina (message or ‘name’), which often takes the form of a riddle or proverb. For Himid, these multicoloured fabrics are ‘speaking clothes’, which employ ‘the language of image, pattern and text through which one woman’s outfit talks to another’s’. Himid’s works engage in a dialogue with each other and with the viewer, both through their individual jina, borrowed from influential writers just as James Baldwin, Sonia Sanchez, Essex Hemphill and Audre Lorde, and through the invitation for visitors to rearrange the hanging works by a system of pulleys to form their own poetry. The suspended Kangas take on a flag-like quality, which, together with the colours and patterns of the fabrics, evoke regimental and ceremonial colonial flag-bearing. -

Lubaina Himid Invisible Strategies Exhibition Notes

2. Le Rodeur: The Lock, 2016 Revenge – A Masque in Five Tableaux 7. Fishing, 1987 9. Mr Salt’s Collection – The Ballad of 3. Le Rodeur: Exchange, 2016 4. Ankledeep, 1991 Fishing was originally part of a larger the Wing series, 1989 After completing this most recent 5. Five, 1991 installation: a cast of cutout painted This work was first shown as part characters roaming across gallery walls. of Himid’s solo exhibition The Ballad series, the artist realised that these 6. Carpet, 1992 interiors were the odd, empty rooms Collectively titled Restoring the Balance, of the Wing at Chisenhale Gallery, of her earlier Plan B paintings, now 8. Unwrapped but not Untied, 1991 these figures appeared within the London, in 1989. It displays the artist’s first retrospective exhibition influence on her practice of populated with a full cast of characters, Himid asserts: ‘After the mourning New Robes for MaShulan, a caricature, particularly eighteenth- and always with a glimpsed view of comes revenge.’ Revenge is at once collaboration with Maud Sulter held at century satirical cartoonists such the sea. They reflect Himid’s complex a monument to the victims of the Rochdale Art Gallery in 1987. In Sulter’s as James Gillray, George Cruikshank 1. Freedom and Change, 1984 personal relationship to water and the transatlantic slave trade, a critique of 10. Bone in the China: Success to the curatorial text, ‘Surveying the Scene’, and William Hogarth. The painting sea: ‘I have never been able to swim the patriarchy, and a space for dialogue. Africa Trade, c.1985 ‘Discourse is a primary tool against the she declared: ‘The show does not stand references the vast collection of properly and am very frightened of This series is a lamentation, an act of weapons used to marginalise and write in isolation. -

Re-Recordings | List of Materials ------9 1) Selection of Material from the Recordings Project Archive, Policy 6 Documents and Art Documentation (ACAA)

Re-Recordings | List of Materials --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 1) Selection of material from the Recordings Project Archive, policy 6 documents and art documentation (ACAA) Recordings: a Select Bibliography of Contemporary African, Afro-Caribbean and Asian 5 British Art. London: INiva, 1996. Race, Sex and Class 5. Multi-Ethnic Education in further, Higher and Community Education, 1983 8 Box of Recordings Research Project and Drafts. Chelsea College of Art & Design Library Archive. Anti-Racist Film Programme. London, GLC, March/April 1985. London GLC/ London 3 Against Racism. 1985. The Arts and Ethnic Minorities: Action Plan. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1986 4 Ward, Liz. St.Martin’s School of Art Library: Collection Development, ILEA Muti-Ethnic 1 Review,Winter/Spring 1985 Chambers, Eddie. Blk Art Group Proposal to Art Colleges, 1983 Black Art in Britain: A bibliography of material held in the Library, Chelsea School of Art, 1986 Asian and Afro-Caribbean British art: a Bibliography of Material Held in the Library, 2 Chelsea College of Art & Design,1989. Art Libraries Journal, The Documentation of Black Artists, v.8, no.4 (Winter 1983) Black Arts in London no.50, 4-17 March 1986 7 African and Asian Visual Artists Archive (Flyer and cards) [Bristol],1990. Arts Council Arts & Ethnic Minorities Action Plan. London, February, 1996 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 2) Artists’ multiples, artists’ books, ephemera and video Araeen, Rasheed. The Golden Verses: a Billboard Artwork… Artangel Trust, 1990 Chambers, Eddie. Breaking that Bondage: Plotting that Course. London: Black Art Gallery, 1984 Us and ‘Dem, The Storey Institute , Leicester, 1994. Postcard/Virginia Nimarkoh, 1993. Artist Book. The Image Employed, the use of narrative in Black art. -

Lubaina Himid

Lubaina Himid Hollybush Gardens launches its new space with an exhibition by Lubaina Himid, a painter and installation artist who has dedicated much of her thirty-year long career to uncovering marginalised and silenced histories, figures and cultural moments. Born in Zanzibar, Lubaina Himid was then brought up in North London by her mother, a Royal College of Art educated textile designer whose keen interest in patterns inspired her to follow an artistic path. Himid first took a BA in Theatre Design at Wimbledon College of Art in the mid-1970s, choosing this discipline for the connections it bore with radical politics, and in particular Black politics. While studying Cultural History at the Royal College of Art six years later, and by then deeply engaged in a struggle against the absence of representation of Black and Asian women in the art world, Lubaina Himid became committed to showing the work of her contem- poraries Sutapa Biswas, Sonia Boyce, Claudette Johnson, Ingrid Pollard, Veronica Ryan and Maud Sulter, alongside her own. She curated significant group exhibitions such as Five Black Women at the Africa Centre in 1983, Black Women Time Now at Battersea Arts Centre in 1983-84 and The Thin Black Line at the Institute for Contemporary Art in 1985, all of which were revisited in the temporary display Thin Black Line(s) at Tate Britain in 2011-12. In 1986, Himid exhibited her iconic installation A Fashionable Marriage at the Pentonville Gallery in London. Inspired by William Hogarth’s Marriage à-la-mode (1743), a series of six paintings satirising an arranged marriage gone wrong, Himid’s piece produced a biting critique of contemporary art and politics, and of their collusion. -

Re Imaging Donald Rodney

Re imaging Donald Rodney 1 Introduction Reimaging Donald Rodney explores the work of Black British artist Donald Rodney (1961 – 1998). It is the first UK exhibition to examine Rodney’s digital practice, and through new commissions expands on the potential of Rodney’s archive as a resource for challenging our conceptions of cultural, physical and social identity. Donald Rodney was considered to be He developed his artistic skills during one the most significant artists of his prolonged periods of hospitalisation, generation. Mark Sealy, Director of resulting in him regularly missing Autography ABP stated in an online school, due to his sickle cell condition. interview with TATE Britain for their After taking an arts foundation collection of Rodney’s work; course at Bournville School of Art in Birmingham he went on to Nottingham “[Along] with Donald, Keith Piper, Eddie Trent, where he met Keith Piper and Chambers and people like Sonia Boyce, Eddie Chambers. Chambers and Piper Lubaina Himid. Those characters in my espoused the notion of Black Art/Black view are really quite seminal in terms of Power, which derived largely from beginning to create an articulate voice… the USA through black writers and he was really interested in working with activists like Ron Karenga. Becoming Exhibition new media and new technologies. One a prominent member of the Blk Arts of the great tragedies is that he was Group, RRodney highlighted the Reimaging Donald Rodney aims to The new works developed for the becoming very articulate within this sociopolitical condition of Britain in Donald Rodney, from encapsulate the digital embodiment exhibition include doublethink (2015), space around the end of his career”. -

Lubaina Himid Warp and Weft

Lubaina Himid Firstsite Lewis Gardens, High Street, Colchester, Essex, CO1 1JH +44 (0) 1206 713 700 | www.firstsite.uk Warp and Weft Naming the Money, 2004, life-size painted cut-out plywood figures, audio. Loaned by the National Museums Liverpool, International Slavery Museum, and the artist. Photo: Spike Island Information Firstsite, Colchester, is delighted to present Warp and Weft, a survey of works by the 2017 Turner Prize nominee, Lubaina Himid. 1 July – 1 October 2017 A key figure in the Black Arts Movement, Himid first came to prominence in the 1980s when Opening event: Friday 30 June, 6 – 9pm she began organising exhibitions of work by her peers, who were underrepresented in the contemporary art scene. Her diverse approach disrupts preconceptions of the world by introducing historical and contemporary stories of racial bias and acts of violence inflicted upon oppressed communities. Himid is best known as a painter, and Warp and Weft is comprised of three bodies of work in which the artist adopts the mantel of the History painter to question its imperialist tradition. By reinserting black figures into this arena of power and prestige, Himid foregrounds the contribution of people of the African diaspora to Western culture and economy. The exhibition’s title, Warp and Weft, refers to the process by which threads are held in tension on a frame or loom to create cloth. Himid chose the title for its reference to Colchester’s important position in the wool trade between the 13th and 16th centuries, and its complex history of race and migration that is reflected in the productive tensions of Himid’s work. -

1 Curriculum Vitae EDDIE CHAMBERS

Curriculum vitae EDDIE CHAMBERS www.eddiechambers.com African Art/African American Art/African Diaspora art history, Field Editor, caa.reviews, (http://www.caareviews.org / http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/2969#.VxlZGaX_R94) appointed August 2014, now serving a second three-year term Member of the editorial board of caa.reviews for a four-year term, from July 1, 2018, to June 30, 2022. Art Monthly Foundation Honorary Patron, (together with Liam Gillick, Hans Haacke, Alfredo Jaar, and Martha Rosler) Appointed June 2018 The University of Texas at Austin Department of Art and Art History 2301 San Jacinto Blvd. Stop D1300 Austin, Texas 78712-1421 EDUCATION Historical and Cultural Studies Department, Goldsmiths College, University of London, (Supervisor, Professor Sarat Maharaj, Internal Examiner, Dr. Carol McKay, External Examiner, Professor Stuart Hall) Black Visual Arts Activity in England 1981-1986: Press and Public Responses, PhD awarded March 31, 1998 Sunderland Polytechnic, Faculty of Art and Design, Fine Art Department, 1980 - 1983. BA (Hons.) Fine Art, 2:1 UT-AUSTIN APPOINTMENT Assistant Professor, Art History, January 2010 – August 2013 Associate Professor, Art History, September 2013 – August 2016 Professor, Art History, September 2016 onwards Inaugural Curatorial Fellow at the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, Fall Semester 2013/Spring Semester 2014 Assistant Chair, Art History Division, Fall 2015 – Summer 2017, two-year term OTHER TEACHING Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Visiting Professor, Art History department, spring semester 2008, and spring semester and fall semester 2009. 1 Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Visiting Professor, Art History department, spring semester and fall semester, 2005 and fall semester 2006. -

Press Release

Hollybush Gardens 1-2 Warner Yard London EC1r 5ey Tel: +44 (0)207 837 5991 www.hollybushgardens.co.uk lubaina himid Exhibition: 7 June - 15 August 2019 Preview: Thursday, 6 June 2019, 6:30 - 8:30 pm Hollybush Gardens is pleased to present a selection of drawings by Lubaina Himid that are being exhibited for the first time. This body of work was produced as part of the research process for what became Tailor, Striker, Singer, Dandy, a series of five painted portraits of black men that developed out of Himid’s encounter with the West African textiles held in the Manchester City Galleries’ extensive collection of historical fashion and clothing. Himid, whose mother was a textile designer, has been fascinated by patterns in garments since childhood. Patterns have populated her work from the 1980s to today, enlivening the visual surface and weaving together disparate threads—cultural, geographical, historical. Himid explains, ‘I love the language of pattern, its immense potential for movement, illusion, colour experiments and subliminal political messaging.' In developing the life-size portraits of Tailor, Striker, Singer, Dandy, Himid produced a body of drawings that interpret and re-contextualise the textiles she found in the collection. Colour, shape, and repetition are taken as devices embedded in clothing that are mobile and malleable, shifting in meaning across contexts. The drawings re-embed historical textile samples and clothing designs in the imagined male figures in anachronistic ways, animating the multi-directional and cross-historical flow of patterns in self-fashioning and identity. Lubaina Himid lives and works in Preston, UK and is a professor at the University of Central Lancashire. -

Motiroti Brochure

motiroti motiroti /The Builders Association’s Alladeen was presented as a cross media perfomance for stage, music video and a web project. It toured internationally (2002-05) to numerous venues and received an OBIE Award in New York. Photo: Simone Lynn. motiroti is a London based arts organisation within visual and live art, new technology led by artistic director Ali Zaidi. For over ten and socially engaged practice, our projects years the company has made internationally are accessible to a wide audience through acclaimed and award winning art that multiple layers of interpretation. We foster transforms relationships between people, the development of a lifelong learning communities and spaces. motiroti works at culture. Learning and art production are the forefront of ever-changing global social part of the same process, and offer equally realities, challenging and teasing perceptions potent opportunities to inspire and develop of artists, institutions and audiences alike. a dynamic exchange between artists and communities. Working with a range of collaborators HITTUCK motiroti is one of the few arts organisations truly to stretch between W international cutting edge work and the lives of people in their own communities. They gain their inspiration from life in all its rich forms – it shows. If only more arts had this breadth of vision. Jenny Edwards, CEO Homeless Link ANDREW PHOTO: This page, clockwise from top right: Harvest it! (2007). Kakatsitsi Drummers performing at the autumn festival in Myatt’s Fields Park. Harvest it! Vassall Voices Children’s Choir. The Seed The Root GOEBEL (1995). From a series A of images installed HITTUCK in Brick Lane. -

Black Art, Black Power: Responses to Soul of a Nation

Black Art, Black Power: Responses to Soul of a Nation Friday 13 October 2017 Starr Cinema, Tate Modern Programme 10.30 Welcome: Richard Martin (Tate) Californian Scenes 10.40 Kellie Jones (Columbia University), ‘South of Pico’ 11.00 Sampada Aranke (School of the Art Institute of Chicago), ‘Death’s Futurity’ 11.20 Discussion, chaired by Zoe Whitley (Tate) 11.50 Break; refreshments in Starr Foyer From Chicago and Washington to Lagos 12.20 Margo Natalie Crawford (University of Pennsylvania), ‘Black Public Interiority, Chicago-Style’ 12.40 Tuliza Fleming (National Museum of African American History and Culture), ‘Jeff Donaldson, FESTAC, and the Washington, D.C., Delegation’ 13.00 Discussion, chaired by Daniel Matlin (King’s College London) 13.30 Lunch New York Photography 14.30 Sherry Turner DeCarava (art historian) and Mark Godfrey (Tate) British Contexts: The Black Arts Movement and Beyond 15.10 Lubaina Himid (artist) and Marlene Smith (artist and curator), chaired by Melanie Keen (Iniva) 16.20 Break; refreshments in Starr Foyer Art in the Age of Black Lives Matter 16.50 Introduction: Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley 17.00 Barby Asante (artist), Kevin Beasley (artist) and Luke Willis Thompson (artist), chaired by Elvira Dyangani Ose (Creative Time and Goldsmiths, University of London) 18.00 Close; reception in Starr Foyer Biographies Sampada Aranke (PhD, Performance Studies) is an Assistant Professor in the Art History, Theory, and Criticism Department at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Her research interests include performance theories of embodiment, visual culture, and black cultural and aesthetic theory. Her work has been published in e-flux , Artforum , Art Journal , Ecquid Novi: African Journalism Studies , and Trans-Scripts: An Interdisciplinary Online Journal in the Humanities and Social Sciences at UC Irvine.