Download (17Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

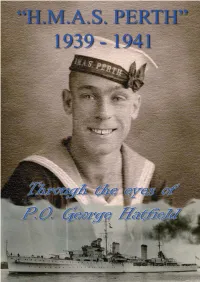

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

Huntsville TX Cincinnati College-Conservatory

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. John W. Lane Associate Professor of Music, Director of Percussion Studies Sam Houston State University Email: [email protected] Office Phone: (936) 294-3593 EDUCATION 2010 Cincinnati Conservatory of Music – Cincinnati, OH Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion Performance D.M.A. Document: Abstracted Resonances: A Study of Performance Practices Reflecting the Influence of Indigenous American Percussive Traditions in the Music of Peter Garland. 2004 University of North Texas – Denton, TX Master of Music in Percussion Performance 2002 Stephen F. Austin State University – Nacogdoches, TX Bachelor of Music (Music Education) TEACHING/WORK HISTORY 2006 – Present Sam Houston State University – Huntsville TX Associate Professor of Percussion, Tenured 2011 Director of Percussion Studies Duties: Applied Percussion, Director of the Sam Houston Percussion Group and Steel Band Administrative Duties: Personnel management (oversee graduate assistant and adjunct duties), Assist the Bearkat Marching Band Drumline, Coordinate teaching rosters/load, Develop applied lesson curriculum 2005-2006 Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music – Cincinnati, OH Graduate Assistant Duties: Percussion Methods, Assisted with the maintenance of the Percussion Studio 2004-2005 University of Wyoming – Laramie, WY Lecturer of Percussion Duties: Applied Percussion, Director of the Percussion Ensemble and Pan Band, Percussion Methods, Public School Jazz Techniques, Instructor for the Western Thunder Marching Band Drumline 2002-2004 University of North Texas – Denton, TX Teaching Fellow Duties: Applied Percussion, Director/Arranger for the UNT Steel Band RESEARCH: SCHOLARLY AND CREATIVE ACCOMPLISHMENTS INTERNATIONAL JURIED PERFORMANCES (invited) 2014 Percussive Arts Society International Convention (PASIC), Indianapolis, IN. [PASIC is the largest gathering of percussionists in the world, bringing together over 150 events with attendance of over 6,000 percussionists, educators, and enthusiasts. -

A Study of the Work of Vladimir Nabokov in the Context of Contemporary American Fiction and Film

A Study of the Work of Vladimir Nabokov in the Context of Contemporary American Fiction and Film Barbara Elisabeth Wyllie School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London For the degree of PhD 2 0 0 0 ProQuest Number: 10015007 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10015007 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Twentieth-century American culture has been dominated by a preoccupation with image. The supremacy of image has been promoted and refined by cinema which has sustained its place as America’s foremost cultural and artistic medium. Vision as a perceptual mode is also a compelling and dynamic aspect central to Nabokov’s creative imagination. Film was a fascination from childhood, but Nabokov’s interest in the medium extended beyond his experiences as an extra and his attempts to write for screen in Berlin in the 1920s and ’30s, or the declared cinematic novel of 1938, Laughter in the Dark and his screenplay for Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 film version of Lolita. -

Year 10 : in the News

Year 10 : In the News Graphic Design Examples of poster designs • Art work that is produced to COMMUNICATE or EXPLAIN an idea, to a group of people. • Graphic designers combine words, symbols and images to create a visual representation of ideas and messages. Propaganda Posters • Today, propaganda is commonly thought of to be false or misleading and the term is commonly used in a derogatory way. However, during WW1 & WW2 these posters were created to spreading ideas or information to further a cause. Keep Calm and Carry On origins • A motivational poster produced by the British government in 1939 in preparation for World War II. The poster was intended to raise the morale of the British public, threatened with air attacks on major cities. Although 2.45 million copies were printed, and although the Blitz did in fact take place, the poster was only rarely publicly displayed and was little known until a copy was rediscovered in 2000 ‘In the News’ Design Brief • Many artists, designers and art movements create artwork inspired by current and relevant topics in the news. Propaganda posters from the World War were used to encourage the public to conform. Russian constructivism came after WW1 to provide structure and like the London Underground Posters to educate the public and finally Banksy and Shepard Fairy design posters and art work to raise awareness of political views. • Investigate appropriate resources and design a poster or piece of artwork that communicates a relevant topic that is in the news. Year 10 : In the News Starting Point We Can Do It! It’s Our Flag We Can Do It!" is an American World War II It's Our Flag Fight for it Work for it. -

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg (Minor editing by Alastair Donald) In preparing this Record I have consulted, wherever possible, the original reports, Battalion War and other Diaries, accounts in Globe and Laurel, etc. The War Office Official Accounts, where extant, the London Gazettes, and Orders in Council have been taken as the basis of events recounted, and I have made free use of the standard histories, eg History of the British Army (Fortescue), History of the Navy (Laird Clowes), Britain's Sea Soldiers (Field), etc. Also the Lives of Admirals and Generals bearing on the campaigns. The authorities consulted have been quoted for each campaign, in order that those desirous of making a fuller study can do so. I have made no pretence of writing a history or making comments, but I have tried to place on record all facts which can show the development of the Corps through the Nineteenth and early part of the Twentieth Centuries. H E BLUMBERG Devonport January, 1934 1 P A R T I 1837 – 1839 The Long Peace On 20 June, 1837, Her Majesty Queen Victoria ascended the Throne and commenced the long reign which was to bring such glory and honour to England, but the year found the fortunes of the Corps at a very low ebb. The numbers voted were 9007, but the RM Artillery had officially ceased to exist - a School of Laboratory and nominally two companies quartered at Fort Cumberland as part of the Portsmouth Division only being maintained. The Portsmouth Division were still in the old inadequate Clarence Barracks in the High Street; Plymouth and Chatham were in their present barracks, which had not then been enlarged to their present size, and Woolwich were in the western part of the Royal Artillery Barracks. -

Egyptian Labor Corps: Logistical Laborers in World War I and the 1919 Egyptian Revolution

EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Kyle J. Anderson August 2017 © 2017 i EGYPTIAN LABOR CORPS: LOGISTICAL LABORERS IN WORLD WAR I AND THE 1919 EGYPTIAN REVOLUTION Kyle J. Anderson, Ph. D. Cornell University 2017 This is a history of World War I in Egypt. But it does not offer a military history focused on generals and officers as they strategized in grand halls or commanded their troops in battle. Rather, this dissertation follows the Egyptian workers and peasants who provided the labor that built and maintained the vast logistical network behind the front lines of the British war machine. These migrant laborers were organized into a new institution that redefined the relationship between state and society in colonial Egypt from the beginning of World War I until the end of the 1919 Egyptian Revolution: the “Egyptian Labor Corps” (ELC). I focus on these laborers, not only to document their experiences, but also to investigate the ways in which workers and peasants in Egypt were entangled with the broader global political economy. The ELC linked Egyptian workers and peasants into the global political economy by turning them into an important source of logistical laborers for the British Empire during World War I. The changes inherent in this transformation were imposed on the Egyptian countryside, but workers and peasants also played an important role in the process by creating new political imaginaries, influencing state policy, and fashioning new and increasingly violent repertoires of contentious politics to engage with the ELC. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

The Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges

The Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges Papers of the 25th Annual CCSC Northeastern Conference April 17-18, 2020 Ramapo College of New Jersey Mahwah, NJ Baochuan Lu, Editor Mihaela Sabin, Regional Editor Southwest Baptist University UNH at Manchester Volume 35, Number 8 April 2020 The Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges (ISSN 1937-4771 print, 1937- 4763 digital) is published at least six times per year and constitutes the refereed papers of regional conferences sponsored by the Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges. Copyright ©2020 by the Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges. Per- mission to copy without fee all or part of this material is granted provided that the copies are not made or distributed for direct commercial advantage, the CCSC copyright notice and the title of the publication and its date appear, and notice is given that copying is by permission of the Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges. To copy otherwise, or to republish, requires a fee and/or specific permission. 2 Table of Contents The Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges Board of Directors 9 CCSC National Partners 11 Regional Committees — 2020 CCSC Northeastern Region 12 Reviewers — 2020 CCSC Northeastern Conference 13 An Overview of Data Analytics: Spreadsheet Modeling, Visualization, and Supervised and Unsupervised Learning 15 Carolyn C. Matheus, Marist College Teaching Database for Freshmen: A Two-Thread Model 33 Yang Wang, Margaret McCoey, Thomas Blum, La Salle University Integrative Learning in CS1: Programming, Sustainability, -

\0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 X 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3

... \0-9\0 and X ... \0-9\0 Grad Nord ... \0-9\0013 ... \0-9\007 Car Chase ... \0-9\1 x 1 Kampf ... \0-9\1, 2, 3 ... \0-9\1,000,000 ... \0-9\10 Pin ... \0-9\10... Knockout! ... \0-9\100 Meter Dash ... \0-9\100 Mile Race ... \0-9\100,000 Pyramid, The ... \0-9\1000 Miglia Volume I - 1927-1933 ... \0-9\1000 Miler ... \0-9\1000 Miler v2.0 ... \0-9\1000 Miles ... \0-9\10000 Meters ... \0-9\10-Pin Bowling ... \0-9\10th Frame_001 ... \0-9\10th Frame_002 ... \0-9\1-3-5-7 ... \0-9\14-15 Puzzle, The ... \0-9\15 Pietnastka ... \0-9\15 Solitaire ... \0-9\15-Puzzle, The ... \0-9\17 und 04 ... \0-9\17 und 4 ... \0-9\17+4_001 ... \0-9\17+4_002 ... \0-9\17+4_003 ... \0-9\17+4_004 ... \0-9\1789 ... \0-9\18 Uhren ... \0-9\180 ... \0-9\19 Part One - Boot Camp ... \0-9\1942_001 ... \0-9\1942_002 ... \0-9\1942_003 ... \0-9\1943 - One Year After ... \0-9\1943 - The Battle of Midway ... \0-9\1944 ... \0-9\1948 ... \0-9\1985 ... \0-9\1985 - The Day After ... \0-9\1991 World Cup Knockout, The ... \0-9\1994 - Ten Years After ... \0-9\1st Division Manager ... \0-9\2 Worms War ... \0-9\20 Tons ... \0-9\20.000 Meilen unter dem Meer ... \0-9\2001 ... \0-9\2010 ... \0-9\21 ... \0-9\2112 - The Battle for Planet Earth ... \0-9\221B Baker Street ... \0-9\23 Matches .. -

Compact Discs and Dvds - Popular, Jazz, Ethno Recent Releases - Spring 2016

Compact Discs and DVDs - Popular, Jazz, Ethno Recent Releases - Spring 2016 Compact Discs 300 Entertainment Highly Suspect. Mister Asylum. 1 sound disc $13.98 300 Entertainment ©2015 TZZE 549128 2 857561005599 Contents: Mister Asylum -- Lost -- Lydia -- Bath Salts -- 23 / Sasha Dobson -- Mom -- Bloodfeather -- F*** Me Up -- Vanity -- Claudeland. Parental Advisory: Explicit Content. Grammy Nominee 2016: Best Rock Album. http://www.tfront.com/p-390736-mister-asylum.aspx Wap, Fetty. Fetty Wap. 1 sound disc $18.98 300 Entertainment ©2015 TZZE 552469 2 814908020226 Contents: Trap Queen -- How We Do Things -- 679 -- Jugg -- Trap Luv -- I Wonder -- Again -- My Way -- Time -- Boomin -- RGF Island -- D.A.M -- No Days Off -- I'm Straight -- Couple Bands -- Rock My Chain -- Rewind. http://www.tfront.com/p-393642-fetty-wap.aspx 429 Records Kidjo, Angelique. Sings. 1 sound disc $15.98 429 Records ©2015 FOTN 16042 2 795041604224 Contents: Malaika -- Ominira -- Kelele -- Fifa -- Otishe -- Bahia -- Petitie Fleur -- Samba Pa Ti -- Mamae -- Naima -- Loloye. Grammy Nominee 2016: Best World Music Album http://www.tfront.com/p-395928-sings.aspx Skaggs, Boz. Fool To Care. 1 sound disc $15.98 429 Records ©2015 FOTN 16032 2 795041603227 Contents: Rich Woman -- I M a Fool to Care -- Hell to Pay -- Small Town Talk -- Last Tango on 16th Street -- There S a Storm a Comin -- I M So Proud -- I Want to See You -- High Blood Pressure -- Full of Fire -- Love Don't Love Nobody -- Whispering Pines. http://www.tfront.com/p-387144-fool-to-care.aspx 4ad Records Beirut. No No No. 1 sound disc $14.98 4ad Records ©2015 FOUR 73525 2 652637352528 Contents: Gibralter -- No No No -- At Once -- August Holland -- As Needed -- Perth -- Pacheco -- Fener -- So Allowed. -

Kipling, Rudyard

Kim Kipling, Rudyard Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. Kim Table Of Content About Phoenix−Edition Copyright 1 Kim Kim by Rudyard Kipling 2 Kim Chapter 1 O ye who tread the Narrow Way By Tophet−flare to judgment Day, Be gentle when 'the heathen' pray To Buddha at Kamakura! Buddha at Kamakura. He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam Zammah on her brick platform opposite the old Ajaib−Gher − the Wonder House, as the natives call the Lahore Museum. Who hold Zam−Zammah, that 'fire−breathing dragon', hold the Punjab, for the great green−bronze piece is always first of the conqueror's loot. There was some justification for Kim − he had kicked Lala Dinanath's boy off the trunnions − since the English held the Punjab and Kim was English. Though he was burned black as any native; though he spoke the vernacular by preference, and his mother−tongue in a clipped uncertain sing−song; though he consorted on terms of perfect equality with the small boys of the bazar; Kim was white − a poor white of the very poorest. The half−caste woman who looked after him (she smoked opium, and pretended to keep a second−hand furniture shop by the square where the cheap cabs wait) told the missionaries that she was Kim's mother's sister; but his mother had been nursemaid in a Colonel's family and had married Kimball O'Hara, a young colour− sergeant of the Mavericks, an Irish regiment. He afterwards took a post on the Sind, Punjab, and Delhi Railway, and his Regiment went home without him. -

Military Themes in British Painting 1815 - 1914

/ Military Themes in British Painting 1815 - 1914. Joan Winifred Martin Hichberger. Submission fcr PhD. University College, London. 1985 1 Abstract. Joan Winifred Martin Hichberger. Military Themes in British Painting 1815-1914. This thesis examines the treatment of the Bzitish Army and military themes, in painting, during the period 1815- 1914. All the works discussed were exhibited at the Royal Academy, which, although it underwent modifications in status, remained the nearest equivalent to a State Institution for Art in Britain. All the paintings shown there were painted with the knowledge that they were to be seen by the controllers of the Academy and the dominant classes of society. It will be inferred then, that the paintings shown there may be taken to have been acceptable to ruling class ideologies, and are therefore instructive of "official" attitudes to military art. Representations of the contemporary Army, in this period, fell into two main catagories - battle paintings and genre depictions of soldiers. Chapters one to three survey battle paintings; studying the relation of this genre to the Academy; the relative popularity of the genre and the career patterns of its practioners. The critical reception of battle pictures at the Academy and certain important public competitions will be noted and considered in the context of contemporary ideologies about art and about the Army and its men. Chapter four discusses the vital concept of "heroism" and its treatment in English military art. In particular, the reasons for the popularity of certain military figures above their peers, in academic art, will be explored. It will be argued that the process of "hero-making" in art was not determined by professional success alone, but was often the result of the intervention of patrons, publicists and pressure groups.