Books and Libraries in Medieval Timbuktu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Office

Country Office Humanitarian Situation Report No. 8 © UNICEF/318A6918/Dicko Reporting Period: 1 January - 31 December 2019 Highlights Situation in Numbers • As of 31 December 2019, 201,429 internally displaced persons (IDPs) were 2,180,000 reported in the country, mainly located in Mopti, Gao, Segou, Timbuktu children in need of humanitarian and Menaka regions. assistance (Mali HRP revised July 2019) • In 2019, UNICEF provided short term emergency distribution of household water treatment and hygiene kits as well as sustainable water supply services to 224,295 people (158,021 for temporary access and 66,274 for 3,900,000 sustainable access) of which 16,425 in December 2019 in Segou, Mopti, people in need Gao, Menaka and Timbuktu regions. (OCHA July 2019) • 135,652 children aged 6 to 59 months were treated for severe acute 201,429 malnutrition in health centers across the country from January to Internally displaced people December 31, 2019. (Commission of Movement of Populations Report, 19 December 2019) • In 2019, UNICEF provided 121,900 children affected by conflict with psychosocial support and other child protection services, of which 7,778 were reached in December 2019. 1,113 Schools closed as of 31st • The number of allegations of recruitment and use by armed groups have December 2019 considerably increased (119 cases only in December) (Education Cluster December • From October to December, a total of 218 schools were reopened (120 in 2019) Mopti region) of which 62 in December. In 2019, 71,274 crises-affected children received learning material through UNICEF΄s support. UNICEF Appeal 2019 US$ 47 million UNICEF’s Response and Funding Status Funding Status* (in US$) Funds received, $11.8M Funding Carry- gap, forward, $28.5M $6.6M *Funding available includes carry-over and funds received in the current year. -

Black History 365.Pdf

BLACK UNIT 1 ANCIENT AFRICA UNIT 2 THE TRANSATLANTIC SLAVE B HISTORY TRADE HTORY UNIT 3 AN INCLUSIVE ACCOUNT OF AMERICAN HISTORY THE AMERICAN SYSTEM — THE FORMING THEREOF UNIT 4 365 EMANCIPATION AND RECONSTRUCTION 365 UNIT 5 Type to enter text THE GREAT MIGRATION AND ITS AFTERMATH American history is longer, larger, UNIT 6 more various, more beautiful, and Lorem ipsum CIVIL RIGHTS AND AMERICAN more terrible than anything anyone JUSTICE has ever said about it. UNIT 7 ~James Baldwin MILTON • FREEMAN THE ECONOMIC SYSTEM BACK UNIT 8 BLACK CULTURE AND INFLUENCE HTORY UNIT 9 AN INCLUSIVE ACCOUNT OF AMERICAN HISTORY TEXAS: ISBN 978-0-9898504-9-0 THE LONE STAR STATE 90000> UNIT 10 THE NORTH STAR: A GUIDE TO 9 780989 850490 FREEDOM AND OPPORTUNITY Dr. Walter Milton, Jr. IN CANADA Joel A. Freeman, PhD BH365 36BH365 51261 Black History An Inclusive Account of American History 365 Black History365 An Inclusive Account of American History BH365 Authors AUTHORS Dr. Walter Milton, Jr. & Joel A. Freeman, Ph.D. Publisher DR. WALTER MILTON, JR., Founder and President of BH365®, LLC CGW365 Publishing P.O Box 151569 Led by Dr. Walter Milton, Jr., a diverse team of seasoned historians and curriculum developers have collective Arlington, Texas 76015 experience in varied education disciplines. Dr. Milton is a native of Rochester, New York. He earned a Bachelor United States of America of Arts degree from the University of Albany and a Master of Science from SUNY College at Brockport. He took blackhistory365education.com postgraduate courses at the University of Rochester to receive his administrative certifications, including his su- ISBN: 978-1-7355196-0-9 perintendent’s license. -

Lessons Learnt from the Reconstruction of the Destroyed Mausoleums of Timbuktu, Mali Thierry Joffroy, Ben Essayouti

Lessons learnt from the reconstruction of the destroyed mausoleums of Timbuktu, Mali Thierry Joffroy, Ben Essayouti To cite this version: Thierry Joffroy, Ben Essayouti. Lessons learnt from the reconstruction of the destroyed mausoleums of Timbuktu, Mali. HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, Sep 2020, Valencia, Spain. pp.913-920, 10.5194/isprs-archives-XLIV-M-1-2020-913-2020. hal-02928898 HAL Id: hal-02928898 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02928898 Submitted on 9 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLIV-M-1-2020, 2020 HERITAGE2020 (3DPast | RISK-Terra) International Conference, 9–12 September 2020, Valencia, Spain LESSONS LEARNT FROM THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE DESTROYED MAUSOLEUMS OF TIMBUKTU, MALI T. Joffroy 1, *, B. Essayouti 2 1 CRAterre-ENSAG, AE&CC, Univ. Grenoble Alpes, Grenoble, France - [email protected] 2 Mission culturelle de Tombouctou, Tombouctou, Mali - [email protected] Commission II - WG II/8 KEY WORDS: World heritage, Post conflict, Reconstruction, Resilience, Traditional conservation ABSTRACT: In 2012, the mausoleums of Timbuktu were destroyed by members of the armed forces occupying the North of Mali. -

Floods Briefing Note – 06 September 2018

MALI Floods Briefing note – 06 September 2018 Heavy rain that began in late July 2018 has caused flooding in several parts of the country. As of late August, more than 18,000 people were affected, 3,200 houses destroyed, and some 1,800 head of cattle killed. The affected populations are in need of shelter, NFI, and WASH assistance. Longer-term livelihoods assistance is highly likely to be needed in the aftermath of the floods. Source: UNICEF 05/10/2014 Anticipated scope and scale Key priorities Humanitarian constraints The rainy season in Mali is expected to continue until October, +18,000 Flooding of roads may delay the response. which will probably cause further flooding. The recrudescence of acts of banditry, people affected looting, kidnappings, and violence Flooding will have a longer-term impact on already vulnerable committed against humanitarian actors is populations affected by conflict, displacement, and drought. 3,200 hindering the response. Crop and cattle damage is likely to negatively impact both houses destroyed food security and livelihoods, and long-term assistance will be needed to counteract the effects of the floods. cattle killed Limitations 1,800 The lack of disaggregated data (both geographic and demographic) limits the evaluation of needs and the identification of specific Livelihoods vulnerabilities. impacted in the long term Any questions? Please contact our senior analyst, Jude Sweeney: [email protected] / +41 78 783 48 25 ACAPS Briefing Note: Floods in Mali Crisis impact peak during the rainy season (between May and October). The damage caused by flooding is increasing the risk of malaria. (WHO 01/05/2018, Government of Mali 11/06/2017) The rainy season in Mali runs from mid-May until October, causing infrastructural WASH: Access to safe drinking water and WASH facilities is poor in Timbuktu region, damage and impacting thousands of people every year. -

USAID MALI CIVIC ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM (CEP-MALI) Year 4 Report (October 01, 2019 – December 31, 2019)

USAID MALI CIVIC ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM (CEP-MALI) Year 4 Report (October 01, 2019 – December 31, 2019) Celebration of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, December 3rd, 2019 Funding provided by the United States Agency for International Development under Cooperative Agreement No. AID-688-A-16-00006 January 2020 Prepared by: FHI 360 Submitted to: USAID Salimata Marico Robert Schmidt Agreement Officer’s Representative/AOR Agreement Officer [email protected] [email protected] Inna Bagayoko Cheick Oumar Coulibaly Alternate AOR Acquisition and Assistance Specialist [email protected] [email protected] 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page i LIST OF ACRONYMS ARPP Advancing Reconciliation and Promoting Peace AOR Agreement Officer Representative AAOR Alternate Agreement Officer Representative AMPPT Association Malienne des Personnes de Petite Taille AFAD Association de Formation et d’Appui du Développement AMA Association Malienne des Albinos ACCORD Appui à la Cohésion Communautaire et les Opportunités de Réconciliation et de Développement CEP Civic Engagement Program CMA Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad COR Contracting Officer Representative COP Chief of Party CPHDA Centre de Promotion des Droits Humains en Afrique CSO Civil Society Organization DCOP Deputy Chief of Party DPO Disabled Person’s Organization EOI Expression of Interest FHI 360 Family Health International 360 FONGIM Fédération des Organisations Internationales Non Gouvernementales au Mali FY Fiscal Year GGB Good Governance Barometer GOM Government of Mali INGOS International -

Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019

FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 MALI ENHANCED MARKET ANALYSIS JUNE 2019 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’Famine views Early expressed Warning inSystem this publications Network do not necessarily reflect the views of the 1 United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Mali Enhanced Market Analysis 2019 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit www.fews.net. Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgments FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Mali who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. Recommended Citation FEWS NET. 2019. Mali Enhanced Market Analysis. Washington, DC: FEWS NET. -

A Peace of Timbuktu: Democratic Governance, Development And

UNIDIR/98/2 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva A Peace of Timbuktu Democratic Governance, Development and African Peacemaking by Robin-Edward Poulton and Ibrahim ag Youssouf UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1998 NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/98/2 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.98.0.3 ISBN 92-9045-125-4 UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research UNIDIR is an autonomous institution within the framework of the United Nations. It was established in 1980 by the General Assembly for the purpose of undertaking independent research on disarmament and related problems, particularly international security issues. The work of the Institute aims at: 1. Providing the international community with more diversified and complete data on problems relating to international security, the armaments race, and disarmament in all fields, particularly in the nuclear field, so as to facilitate progress, through negotiations, towards greater security for all States and towards the economic and social development of all peoples; 2. Promoting informed participation by all States in disarmament efforts; 3. Assisting ongoing negotiations in disarmament and continuing efforts to ensure greater international security at a progressively lower level of armaments, particularly nuclear armaments, by means of objective and factual studies and analyses; 4. -

Timbuktu Civilization and Its Significance in Islamic History

E-ISSN 2039-2117 Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 4 No 11 ISSN 2039-9340 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy October 2013 Timbuktu Civilization and its Significance in Islamic History Abdi O. Shuriye Dauda Sh. Ibrahim Faculty of Engineering International Islamic University Malaysia E mail: [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n11p696 Abstract Timbuktu civilization began as a seasonal settlement for trade caravans in the early 11th century. It later flourished in trade and as one of the early African centres of Islamic culture. This paper reviews the trend of Timbuktu civilization from prehistoric period up to the current state of its political impact of the region. The paper further focuses on the role Timbuktu played in African history by serving as academic and commercial centre. The significant of this paper is to reveal the fact that Africa has a long Islamic civilization. The paper provides evidences from reliable sources of the symbolic representation of the impact and influence of the early schools and universities between 11th and 15th century that existed in West Africa. The manuscript of Timbuktu serves as a living testimony of the highly advanced and refined civilization in Africa during the middle ages. The history of monuments, artefacts as well as architectural land marks that signifies the historical origin of this ancient city is presented. The early heroes that stood firm towards the development and civilisation of Timbuktu are outlined. Analysis of the development as well as the factors that led to the civilization is presented in this paper. Keywords: Timbuktu, civilization, Islamic History, Africa. -

Humanitarian Access (Summary of Constraints from January to December 2017)

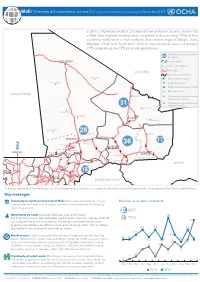

Mali: Overview of humanitarian access (summary of constraints from January to December 2017) In 2017, OCHA recorded 133 cases of humanitarian access constraints in Mali (the highest number ever recorded in the country). 97% of the incidents took place in the northern and central regions (Mopti, Gao, Ménaka, Kidal and Timbuktu). 41% of the incidents were robberies, 27% carjackings and 9% physical aggression. Number of access constraints xx by region TAOUDÉNIT Limit of region Limit of new regions ALGERIA Main road International boundaries Achourat! Non-functional airport Foum! Elba Functional airport Regional administrative centre ! Populated place MAURITANIA ! Téssalit Violence against humanitarian workers on locations Violence against humanitarian 31 workers on roads !Abeïbara ! Arawane Boujbeha! KIDAL ! Tin-Essako ! Anefif Al-Ourche! 28 ! Inékar Bourem! TIMBUKTU ! Gourma- 17 Rharous Goundam! 36 Diré! GAO 2 ! Niafunké ! Tonka ! BAMAKO Léré Gossi ! ! MÉNAKA Ansongo ! ! Youwarou! Anderamboukane Ouattagouna! Douentza ! NIGER MOPTI Ténénkou! 1 Bandiagara! 18 Koro! Bankass! SÉGOU Djenné! BURKINA FASO The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Key messages Insecurity in northern and central Mali: Both areas are experiencing an Number of access constraints unprecedented level of criminality, terrorism and armed conflict directly impeding access. 133 2017 Movement on road: Ansongo-Ménaka, Gao-Anefis-Kidal, 18 Timbuktu-Goundam, Bambara Maoudé-Timbuktu road axis are very difficult 68 2016 to navigate during the rainy season. Armed groups’presence requires 17 ongoing negotiations at different levels prior to using roads. Humanitarians are mostly victim of criminal activities on roads. 13 13 13 11 Aerial access: Existing airports allow access to regional capitals and big 11 9 9 9 cities in Bamako, Timbuktu, Gao and Mopti. -

Getting to Know the K Umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018

Getting to Know the K umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018 Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Getting to Know the K umbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum Brazil, 1818-2018 Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Slave Societies Digital Archive Press Nashville 2021 3 Publication of this book has been supported by grants from the Fundaçāo de Amparo à Pesquisa do Rio de Janeiro; the Museu Nacional/ Getting to Know Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro/Brazil; and the Slave Societies Digital Archive/Vanderbilt University. the K umbukumbu Originally published as: Conhecendo a exposição Kumbukumbu Exhibition at the do Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional, 2016). National Museum English edition copyright © 2021 Slave Societies Digital Archive Press Brazil, 1818-2018 ______________ Slave Societies Digital Archive Press 2301 Vanderbilt Pl., PMB 351802, Nashville, TN, 37235, United States Authors: Soares, Mariza de Carvalho, 1951; Agostinho, Michele de Barcelos, 1980; Lima, Rachel Correa, 1966. Title: Getting to Know the Kumbukumbu Exhibition at the National Museum, Brazil, 1818-2018 First Published 2021 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-578-91682-8 (cover photo) Street market. Aneho, Togo. 4 Photo by Milton Guran. 5 Project A New Room for the African Collection Director João Pacheco de Oliveira Curator Mariza de Carvalho Soares 6 7 Catalogue Team Research Mariza de Carvalho Soares Michele de Barcelos Agostinho Rachel Corrêa Lima Carolina Cabral Aline Chaves Rabelo Drawings Maurílio de Oliveira Photographs of the Collection Roosevelt Mota Graphic Design UMAstudio - Clarisse Sá Earp Translated by Cecília Grespan Edited by Kara D. -

The United Nations Foundation Team Traveled to Bamako, Gao, And

The United Nations Foundation team traveled to Bamako, Gao, and Timbuktu from September 16-26, 2018, to learn more about the United Nations Integrated Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). During our visit, we met with more than 50 UN officials, civil society groups, Western diplomats, and international forces including leadership in MINUSMA, Barkhane, and the G5 Sahel Joint Force. Below you will find our observations. Background The landlocked country of Mali, once a French colony and a cultural hub of West Africa, was overrun in January 2012 by a coalition of Tuareg and terrorist groups moving south towards the capital of Bamako. At the time, the Tuareg movement (MNLA) in northern Mali held legitimate grievances against the government and aligned itself with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and Ansar Dine (Defenders of Faith), the Islamic militants and jihadists in the region. Simultaneously, a mutiny of soldiers launched a military coup d’ etat led by Captain Amadou Sonogo, who took power from then President Amadou Toumani Touré and dissolved government institutions, consequently leading to a complete collapse of institutions in the northern part of the country. This Tuareg movement declared Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu an Independent State of Azawad by April 2012. However, soon after, the Tuareg move- ment was pushed out by the jihadists, Ansar Dine and Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO).1 In the early days of the conflict, the UN and Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) put together a power-sharing framework which led to the resignation of President Toure. Dioncounda Traoré was subsequently appointed interim President and a transitional government was established. -

In Goundam and Dire, Timbuktu 2009/2010

Scaling-up the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) in Goundam and Dire, Timbuktu 2009/2010 by Erika Styger Africare, Goundam and Africare, Bamako February 28, 2010 Table of Contents List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ii Acknowledgments ii Executive Summary iii Introduction 1 Methodology 1 Results 4 A) Scaling up SRI in 28 villages 4 1. Number of farmers’ participating in SRI extension 4 2. Rice grain yield 7 3. Rice variety performance 9 4. Yield parameters 10 5. Crop management 11 B) Innovations 13 6. Rice variety test using SRI methods 13 7. Irrigation test 16 8. Introduction of hand tractor 17 9. Composting Activities 21 10. The System of Wheat Intensification 23 Conclusions and recommendations 27 Bibliography 29 List of Tables Table 1: Characteristics of the rice-growing villages in the four communes 2 Arham, Kondi, Bourem and Douekire Table 2: Number of SRI farmers and SRI surface area for 28 villages (2009/2010) 6 Table 3: SRI and farmer practice yield in Goundam and Dire Circles, 2009/2010 7 Table 4: Planting parameters for SRI and control plots 8 Table 5: Rice grain yield (kg/ha) for six varieties used in SRI plots and farmers’ 10 fields Table 6: Yield parameters for SRI and farmer field plots 10 Table 7: Percentage of farmers executing different crop management tasks for 11 SRI plots and farmer fields. Table 8: Percentage of farmers using cono-weeders from one to four times 11 in the 2008 and 2009 cropping season Table 9: Time needed for weeding SRI plots and conventional plots (in person 12 day/ha) Table 10: Fertilization of SRI plots and farmer fields 12 Table 11: Name and characteristics of 15 varieties included in SRI performance 13 test Table 12: Yield and yield parameters of 15 varieties under SRI cultivation 14 methods Table 13.