Ancient Ghana and Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal by Nikolas Sweet a Dissertation Submitte

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal By Nikolas Sweet A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee Professor Judith Irvine, chair Associate Professor Michael Lempert Professor Mike McGovern Professor Barbra Meek Professor Derek Peterson Nikolas Sweet [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3957-2888 © 2019 Nikolas Sweet This dissertation is dedicated to Doba and to the people of Taabe. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field work conducted for this dissertation was made possible with generous support from the National Science Foundation’s Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the University of Michigan Rackham International Research Award. Many thanks also to the financial support from the following centers and institutes at the University of Michigan: The African Studies Center, the Department of Anthropology, Rackham Graduate School, the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies, the Mellon Institute, and the International Institute. I wish to thank Senegal’s Ministère de l'Education et de la Recherche for authorizing my research in Kédougou. I am deeply grateful to the West African Research Center (WARC) for hosting me as a scholar and providing me a welcoming center in Dakar. I would like to thank Mariane Wade, in particular, for her warmth and support during my intermittent stays in Dakar. This research can be seen as a decades-long interest in West Africa that began in the Peace Corps in 2006-2009. -

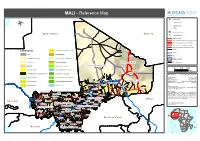

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

Decomposing Gender and Ethnic Earnings Gaps in Seven West African Cities

DOCUMENT DE TRAVAIL DT/2009-07 Decomposing Gender and Ethnic Earnings Gaps in Seven West African Cities Christophe NORDMAN Anne-Sophie ROBILLIARD François ROUBAUD DIAL • 4, rue d’Enghien • 75010 Paris • Téléphone (33) 01 53 24 14 50 • Fax (33) 01 53 24 14 51 E-mail : [email protected] • Site : www.dial.prd.fr DECOMPOSING GENDER AND ETHNIC EARNINGS GAPS IN SEVEN WEST AFRICAN CITIES Christophe Nordman Anne Sophie Robilliard François Roubaud IRD, DIAL, Paris IRD, DIAL, Dakar IRD, DIAL, Hanoï [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Document de travail DIAL Octobre 2009 Abstract In this paper, we analyse the size and determinants of gender and ethnic earnings gaps in seven West African capitals (Abidjan, Bamako, Cotonou, Dakar, Lome, Niamey and Ouagadougou) based on a unique and perfectly comparable dataset coming from the 1-2-3 Surveys conducted in the seven cities from 2001 to 2002. Analysing gender and ethnic earnings gaps in an African context raises a number of important issues that our paper attempts to address, notably by taking into account labour allocation between public, private formal and informal sectors which can be expected to contribute to earnings gaps. Our results show that gender earnings gaps are large in all the cities of our sample and that gender differences in the distribution of characteristics usually explain less than half of the raw gender gap. By contrast, majority ethnic groups do not appear to have a systematic favourable position in the urban labour markets of our sample of countries and observed ethnic gaps are small relative to gender gaps. -

Thesis.Pdf (8.305Mb)

Faculty of Humanities, and Social Science and Education BETWEEN ALIENATION AND BELONGING IN NORTHERN GHANA The voices of the women in the Gambaga ‘witchcamp’ Larry Ibrahim Mohammed Thesis submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies June 2020 i BETWEEN ALIENATION AND BELONGING IN NORTHERN GHANA The voices of the women in the Gambaga ‘witchcamp’ By Larry Ibrahim Mohammed Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education UIT-The Arctic University of Norway Spring 2020 Cover Photo: Random pictures from the Kpakorafon in Gambaga Photos taken by: Larry Ibrahim Mohammed i ii DEDICATION To my parents: Who continue to support me every stage of my life To my precious wife: Whose love and support all the years we have met is priceless. To my daughters Naeema and Radiya: Who endured my absence from home To all lovers of peace and advocates of social justice: There is light at the end of the tunnel iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to a lot of good people whose help has been crucial towards writing this research. My supervisor, Michael Timothy Heneise (Assoc. Professor), has been a rock to my efforts in finishing this thesis. I want to express my profound gratitude and thanks to him for his supervision. Our video call sessions within the COVID-19 pandemic has been of help to me. Not least, it has helped to get me focused in those stressful times. Michael Heneise has offered me guidance through his comments and advice, shaping up my rough ideas. Any errors in judgement and presentation are entirely from me. -

AFCP Projects at World Heritage Sites

CULTURAL HERITAGE CENTER – BUREAU OF EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS – U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE AFCP Projects at World Heritage Sites The U.S. Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation supports a broad range of projects to preserve the cultural heritage of other countries, including World Heritage sites. Country UNESCO World Heritage Site Projects Albania Historic Centres of Berat and Gjirokastra 1 Benin Royal Palaces of Abomey 2 Bolivia Jesuit Missions of the Chiquitos 1 Bolivia Tiwanaku: Spiritual and Political Centre of the Tiwanaku 1 Culture Botswana Tsodilo 1 Brazil Central Amazon Conservation Complex 1 Bulgaria Ancient City of Nessebar 1 Cambodia Angkor 3 China Mount Wuyi 1 Colombia National Archeological Park of Tierradentro 1 Colombia Port, Fortresses and Group of Monuments, Cartagena 1 Dominican Republic Colonial City of Santo Domingo 1 Ecuador City of Quito 1 Ecuador Historic Centre of Santa Ana de los Ríos de Cuenca 1 Egypt Historic Cairo 2 Ethiopia Fasil Ghebbi, Gondar Region 1 Ethiopia Harar Jugol, the Fortified Historic Town 1 Ethiopia Rock‐Hewn Churches, Lalibela 1 Gambia Kunta Kinteh Island and Related Sites 1 Georgia Bagrati Cathedral and Gelati Monastery 3 Georgia Historical Monuments of Mtskheta 1 Georgia Upper Svaneti 1 Ghana Asante Traditional Buildings 1 Haiti National History Park – Citadel, Sans Souci, Ramiers 3 India Champaner‐Pavagadh Archaeological Park 1 Jordan Petra 5 Jordan Quseir Amra 1 Kenya Lake Turkana National Parks 1 1 CULTURAL HERITAGE CENTER – BUREAU OF EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS – U.S. DEPARTMENT -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Diapositive 1

Source: ORIGIN - AFRICA Voyager Autrement en Mauritanie Circuit Les espaces infinis du pays des sages Circuit de 11 jours / 10 nuits Du 08 au 18 mars 2021, du 15 au 25 novembre 2021, Du 7 au 17 mars 2022 (tarifs susceptibles d’être révisés pour ce départ) Votre voyage en Mauritanie A la croisée du Maghreb et de l’Afrique subsaharienne, la Mauritanie est un carrefour de cultures, et ses habitants sont d’une hospitalité et d’une convivialité sans pareils. Oasis, source d’eau chaude, paysages somptueux de roches et de dunes…, cette destination vous surprendra par la poésie de ses lieux et ses lumières changeantes. Ce circuit vous permettra de découvrir les immensités sahariennes et les héritages culturels de cette destination marquée par sa diversité ethnique. Depuis Nouakchott, vous emprunterez la Route de l’Espoir pour rejoindre les imposants massifs tabulaires du Tagant et vous régaler de panoramas splendides. Vous rejoindrez l’Adrâr et ses palmeraies jusqu’aux dunes de l’erg Amatlich, avant d’arriver aux villages traditionnels de la Vallée Blanche. Après avoir découvert l’ancienne cité caravanière de Chinguetti, vous échangerez avec les nomades pour découvrir la vie dans un campement. Vous terminerez votre périple en rejoignant la capitale par la cuvette de Yagref. Ceux qui le souhaitent pourront poursuivre leur voyage par une découverte des Bancs d’Arguin. VOYAGER AUTREMENT EN MAURITANIE…EN AUTREMENT VOYAGER Les points forts de votre voyage : Les paysages variés des grands espaces Les anciennes cités caravanières La découverte de la culture nomade Source: ORIGIN - AFRICA Un groupe limité à 12 personnes maximum Circuit Maroc Algérie Mauritanie Chinguetti Atar Adrar Tounguad Ksar El Barka Mali Nouakchott Moudjeria Sénégal Les associations et les acteurs de développement sont des relais privilégiés pour informer les voyageurs sur les questions de santé, d’éducation, de développement économique. -

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune

FINAL REPORT Quantitative Instrument to Measure Commune Effectiveness Prepared for United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Mali Mission, Democracy and Governance (DG) Team Prepared by Dr. Lynette Wood, Team Leader Leslie Fox, Senior Democracy and Governance Specialist ARD, Inc. 159 Bank Street, Third Floor Burlington, VT 05401 USA Telephone: (802) 658-3890 FAX: (802) 658-4247 in cooperation with Bakary Doumbia, Survey and Data Management Specialist InfoStat, Bamako, Mali under the USAID Broadening Access and Strengthening Input Market Systems (BASIS) indefinite quantity contract November 2000 Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS.......................................................................... i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................... ii 1 INDICATORS OF AN EFFECTIVE COMMUNE............................................... 1 1.1 THE DEMOCRATIC GOVERNANCE STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE..............................................1 1.2 THE EFFECTIVE COMMUNE: A DEVELOPMENT HYPOTHESIS..........................................2 1.2.1 The Development Problem: The Sound of One Hand Clapping ............................ 3 1.3 THE STRATEGIC GOAL – THE COMMUNE AS AN EFFECTIVE ARENA OF DEMOCRATIC LOCAL GOVERNANCE ............................................................................4 1.3.1 The Logic Underlying the Strategic Goal........................................................... 4 1.3.2 Illustrative Indicators: Measuring Performance at the -

Remembering Joseph Schacht (1902‑1969) by Jeanette Wakin ILSP

ILSP Islamic Legal Studies Program Harvard Law School Remembering Joseph Schacht (1902-1969) by Jeanette Wakin Occasional Publications January © by the Presdent and Fellows of Harvard College All rghts reserved Prnted n the Unted States of Amerca ISBN --- The Islamic Legal Studies Program s dedcated to achevng excellence n the study of Islamc law through objectve and comparatve methods. It seeks to foster an atmosphere of open nqury whch em- braces many perspectves, both Muslm and non-Mus- lm, and to promote a deep apprecaton of Islamc law as one of the world’s major legal systems. The man focus of work at the Program s on Islamc law n the contemporary world. Ths focus accommodates the many nterests and dscplnes that contrbute to the study of Islamc law, ncludng the study of ts wrt- ngs and hstory. Frank Vogel Director Per Bearman Associate Director Islamc Legal Studes Program Pound Hall Massachusetts Ave. Cambrdge, MA , USA Tel: -- Fax: -- E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/ILSP Table of Contents Preface v Text, by Jeanette Wakin Bblography v Preface The followng artcle, by the late Jeanette Wakn of Columba Unversty, a frend of our Program and one of the leaders n the field of Islamc legal studes n the Unted States, memoralzes one of the most famous of Western Islamc legal scholars, her men- tor Joseph Schacht (d. ). Ths pece s nvaluable for many reasons, but foremost because t preserves and relably nterprets many facts about Schacht’s lfe and work. Equally, however—especally snce t s one of Prof. -

Stamps from Mali Were of Relatively Large Size and Compared to Surface Mail Stamps Their Topics Were Directed More Towards International Events and Organizations

African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH Paper 30; Jan Jansen Mali, April 2018 African Studies Centre Leiden African Postal Heritage APH Paper 30 Jan Jansen Stamp Emissions as a Sociological and Cultural Force – The Case of Mali Introduction Postage stamps and related objects are miniature communication tools, and they tell a story about cultural and political identities and about artistic forms of identity expressions. They are part of the world’s material heritage, and part of history. Ever more of this postal heritage becomes available online, published by stamp collectors’ organizations, auction houses, commercial stamp shops, online catalogues, and individual collectors. Virtually collecting postage stamps and postal history has recently become a possibility. These working papers about Africa are examples of what can be done. But they are work-in-progress! Everyone who would like to contribute, by sending corrections, additions, and new area studies can do so by sending an email message to the APH editors: Ton Dietz ([email protected]) and/or Jan Jansen ([email protected]). You are welcome! Disclaimer: illustrations and some texts are copied from internet sources that are publicly available. All sources have been mentioned. If there are claims about the copy rights of these sources, please send an email to [email protected], and, if requested, those illustrations will be removed from the next version of the working paper concerned. 1 African Postal Heritage; African Studies Centre Leiden; APH -

Al-'Usur Al-Wusta, Volume 23 (2015)

AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ 23 (2015) THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS About Middle East Medievalists (MEM) is an international professional non-profit association of scholars interested in the study of the Islamic lands of the Middle East during the medieval period (defined roughly as 500-1500 C.E.). MEM officially came into existence on 15 November 1989 at its first annual meeting, held ni Toronto. It is a non-profit organization incorporated in the state of Illinois. MEM has two primary goals: to increase the representation of medieval scholarship at scholarly meetings in North America and elsewhere by co-sponsoring panels; and to foster communication among individuals and organizations with an interest in the study of the medieval Middle East. As part of its effort to promote scholarship and facilitate communication among its members, MEM publishes al-ʿUṣūr al-Wusṭā (The Journal of Middle East Medievalists). EDITORS Antoine Borrut, University of Maryland Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University MANAGING EDITOR Christiane-Marie Abu Sarah, University of Maryland EDITORIAL BOARD, BOARD OF DIRECTORS, AL-ʿUṢŪR AL-WUSṬĀ (THE JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS) MIDDLE EAST MEDIEVALISTS Zayde Antrim, Trinity College President Sobhi Bourdebala, University of Tunis Matthew S. Gordon, Miami University Muriel Debié, École Pratique des Hautes Études Malika Dekkiche, University of Antwerp Vice-President Fred M. Donner, University of Chicago Sarah Bowen Savant, Aga Khan University David Durand-Guédy, Institut Français de Recherche en Iran and Research -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10,