Pity and Pardon in Scorsese's Palimpsest, Bringing out the Dead

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

Executive Producer)

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES STEVEN SODERBERGH (Executive Producer) Steven Soderbergh has produced or executive-produced a wide range of projects, most recently Gregory Jacobs' Magic Mike XXL, as well as his own series "The Knick" on Cinemax, and the current Amazon Studios series "Red Oaks." Previously, he produced or executive-produced Jacobs' films Wind Chill and Criminal; Laura Poitras' Citizenfour; Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, and Who Is Bernard Tapie?; Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin; the HBO documentary His Way, directed by Douglas McGrath; Lodge Kerrigan's Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs) and Keane; Brian Koppelman and David Levien's Solitary Man; Todd Haynes' I'm Not There and Far From Heaven; Tony Gilroy's Michael Clayton; George Clooney's Good Night and Good Luck and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind; Scott Z. Burns' Pu-239; Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly; Rob Reiner's Rumor Has It...; Stephen Gaghan'sSyriana; John Maybury's The Jacket; Christopher Nolan's Insomnia; Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi; Anthony and Joseph Russo's Welcome to Collinwood; Gary Ross' Pleasantville; and Greg Mottola's The Daytrippers. LODGE KERRIGAN (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Writer, Director) Co-Creators and Executive Producers Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz wrote and directed all 13 episodes of “The Girlfriend Experience.” Prior to “The Girlfriend Experience,” Kerrigan wrote and directed the features Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs), Keane, Claire Dolan and Clean, Shaven. His directorial credits also include episodes of “The Killing” (AMC / Netflix), “The Americans” (FX), “Bates Motel” (A&E) and “Homeland” (Showtime). -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

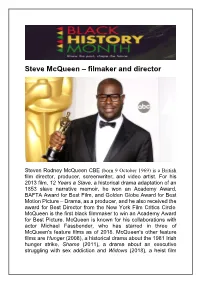

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

GIORGIO MORODER Album Announcement Press Release April

GIORGIO MORODER TO RELEASE BRAND NEW STUDIO ALBUM DÉJÀ VU JUNE 16TH ON RCA RECORDS ! TITLE TRACK “DÉJÀ VU FEAT. SIA” AVAILABLE TODAY, APRIL 17 CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO “DÉJÀ VU FEATURING SIA” DÉJÀ VU ALBUM PRE-ORDER NOW LIVE (New York- April 17, 2015) Giorgio Moroder, the founder of disco and electronic music trailblazer, will be releasing his first solo album in over 30 years entitled DÉJÀ VU on June 16th on RCA Records. The title track “Déjà vu featuring Sia” is available everywhere today. Click here to listen now! Fans who pre-order the album will receive “Déjà vu feat. Sia” instantly, as well as previously released singles “74 is the New 24” and “Right Here, Right Now featuring Kylie Minogue” instantly. (Click hyperlinks to listen/ watch videos). Album preorder available now at iTunes and Amazon. Giorgio’s long-awaited album DÉJÀ VU features a superstar line up of collaborators including Britney Spears, Sia, Charli XCX, Kylie Minogue, Mikky Ekko, Foxes, Kelis, Marlene, and Matthew Koma. Find below a complete album track listing. Comments Giorgio Moroder: "So excited to release my first album in 30 years; it took quite some time. Who would have known adding the ‘click’ to the 24 track would spawn a musical revolution and inspire generations. As I sit back readily approaching my 75th birthday, I wouldn’t change it for the world. I'm incredibly happy that I got to work with so many great and talented artists on this new record. This is dance music, it’s disco, it’s electronic, it’s here for you. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

INTRODUCTION Fatal Attraction and Scarface

1 introduction Fatal Attraction and Scarface How We Think about Movies People respond to movies in different ways, and there are many reasons for this. We have all stood in the lobby of a theater and heard conflicting opin- ions from people who have just seen the same film. Some loved it, some were annoyed by it, some found it just OK. Perhaps we’ve thought, “Well, what do they know? Maybe they just didn’t get it.” So we go to the reviewers whose business it is to “get it.” But often they do not agree. One reviewer will love it, the next will tell us to save our money. What thrills one person may bore or even offend another. Disagreements and controversies, however, can reveal a great deal about the assumptions underlying these varying responses. If we explore these assumptions, we can ask questions about how sound they are. Questioning our assumptions and those of others is a good way to start think- ing about movies. We will soon see that there are many productive ways of thinking about movies and many approaches that we can use to analyze them. In Dragon: The Bruce Lee Story (1992), the actor playing Bruce Lee sits in an American movie theater (figure 1.1) and watches a scene from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) in which Audrey Hepburn’s glamorous character awakens her upstairs neighbor, Mr Yunioshi. Half awake, he jumps up, bangs his head on a low-hanging, “Oriental”-style lamp, and stumbles around his apart- ment crashing into things. -

Death, Medicine, and Religious Solidarity in Martin Scorsese's Bringing out the Dead

Death, Medicine, and Religious Solidarity in Martin Scorsese's Bringing Out the Dead David M. Hammond, Beverly J. Smith Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, Volume 7, Number 3, Summer 2004, pp. 109-123 (Article) Published by Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/log.2004.0027 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/170325 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] 06-logos-hammond2-pp109-123 5/25/04 9:37 AM Page 109 David M. Hammond and Beverly J. Smith Death, Medicine, and Religious Solidarity in Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead In this paper, we will discuss the portrait of medicine in Martin Scorsese’s film, Bringing Out the Dead. Medicine is frequently represented in films as a metaphor for religion, developing a rela- tionship anthropologists have explored for over a century. In a cul- ture of technology and secularization, it might seem this relationship would have necessarily faded. However, despite today’s unprece- dented attempts to frustrate death,1 medicine still must surrender to human mortality. Informed by a religious critique, Bringing Out the Dead suggests that medicine, ideally, is “less about saving lives than about bearing witness,” as Frank Pierce, the central character in the movie, puts it. To put this suggestion into context, we will describe the relationship between religion and medicine evident in the movie as seen from anthropological and theological perspectives. The essential claim of Scorsese’s film is that redemption is avail- able only by bearing witness to a common human solidarity. -

Movie Draft: Below the Belt

POOP READING Movie Draft: Below the Belt Alas, with Bale directing the project and shepherding it by Jameson Simmons through every stage of its tortured development, this tone-deafness extends beyond the lead character. Dialogue You often hear of film studios indulging a star's will sometimes switch from serious to goofy and back in a character-based "passion project" in order to garner their single breath. Entire scenes will be elaborately staged in cooperation for some mass-appeal popcorn movie with no order to set up a double-entendre about a walk-on character. artistic integrity (but an automatic greenlight). The way There's an interlude in Blackie Shepherd's Skid Row Sandra Bullock was granted authority to make Hope Floats encampment in which the camera follows two rats having a so she'd acquiesce to appear in the floating turd that was belching contest. At first there's hope that it will be one of Speed 2: Cruise Control. But in this case, the scenario is those movies that's just incompetent enough to be turned entirely on its ear: to convince Christian Bale to unintentionally funny, but it quickly surpasses that threshold. appear in his Oscar-nominated turn in The Fighter, Below the Belt is best left to future film historians – as a Paramount had to finance Below the Belt, the slapstick karate puzzling glimpse into the madness that can envelop a great goof that Bale had spent 13 years developing as a Chris performer when he sets his mind to the wrong task. Farley tribute. Below the Belt is rated R. -

Top 30 Films

March 2013 Top 30 Films By Eddie Ivermee Top 30 films as chosen by me, they may not be perfect or to everyone’s taste. Like all good art however they inspire debate. Why Do I Love Movies? Eddie Ivermee For that feeling you get when the lights get dim in the cinema Because of getting to see Heath Ledger on the big screen for the final time in The Dark Knight Because of Quentin Tarentino’s knack for rip roaring dialogue Because of the invention of the steadicam For saving me from the drudgery of nightly weekly TV sessions Because of Malik’s ability to make life seem more beautiful than it really is Because of Brando and Pacino together in The Godfather Because of the amazing combination of music and image, e.g. music in Jaws Because of the invention of other worlds, see Avatar, Star Wars, Alien etc. For making us laugh, cry, sad, happy, scared all in equal measure. For the ending of the Shawshank Redemption For allowing Jim Carey lose during the 1990’s For arranging a coffee date on screen of De Niro an Pacino For allowing Righteous Kill to go straight to DVD so I could turn it off For taking me back in time with classics like Psycho, Wizard of Oz ect For making dreams become reality see E.T, The Goonies, Spiderman, Superman For allowing Brad Pitt, Michael Fassbender, Tom Hardy and Joesph Gordon Levitt ply their trade on screen for our amusement. Because of making people Die Hard as Rambo strikes with a Lethal Weapon because he is a Predator who is also Rocky. -

Saturday Night Marquee Every Saturday Hdnet Movies Rolls out the Red Carpet and Shines the Spotlight on Hollywood Blockbusters, Award Winners and Memorable Movies

August 2015 HDNet Movies delivers the ultimate movie watching experience – uncut - uninterrupted – all in high definition. HDNet Movies showcases a diverse slate of box-office hits, iconic classics and award winners spanning the 1950s to 2000s. HDNet Movies also features kidScene, a daily and Friday Night program block dedicated to both younger movie lovers and the young at heart. For complete movie schedule information, visit www.hdnetmovies.com. Follow us on Twitter: @HDNetMovies and on Facebook. Saturday Night Marquee Every Saturday HDNet Movies rolls out the red carpet and shines the spotlight on Hollywood Blockbusters, Award Winners and Memorable Movies Saturday, August 1st Saturday, August 15th Who Ya Gonna Call? Laugh Out Loud Saturday Ghostbusters Down Periscope Starring Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, Sigourney Starring Kelsey Grammer, Lauren Holly, Rob Weaver Directed by Ivan Reitman Schneider. Directed by David Ward Ghostbusters II Tootsie Starring Bill Murray, Dan Aykroyd, Sigourney Starring Dustin Hoffman, Jessica Lange, Teri Garr Weaver Directed by Sydney Pollack Directed by Ivan Reitman Roxanne Saturday, August 8th Starring Steve Martin, Daryl Hannah, Rick Rossovich Leading Ladies Directed by Fred Schepisi Courage Under Fire Starring Meg Ryan, Denzel Washington, Matt Raising Arizona Damon Starring Nicolas Cage, Holly Hunter, John Goodman Directed by Edward Zwick Directed by Joel Coen Silence of the Lambs Saturday, August 22nd Starring Jodie Foster, Anthony Hopkins, Scott Glenn Adventure Time Directed by Jonathan Demme Romancing the Stone Starring Michael Douglas, Kathleen Turner, Danny Devito. Directed by Robert Zemeckis The River Wild Starring Meryl Streep, Kevin Bacon, David Strathairn Directed by Curtis Hanson 1 Make kidScene your destination every day and Make kidScene Friday Night your family’s weekly movie night. -

The Last Station

Mongrel Media Presents The Last Station A Film by Michael Hoffman (112 min, Germany, Russia, UK, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html THE LAST STATION STARRING HELEN MIRREN CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER PAUL GIAMATTI ANNE-MARIE DUFF KERRY CONDON and JAMES MCAVOY WRITTEN & DIRECTED BY MICHAEL HOFFMAN PRODUCED BY CHRIS CURLING JENS MEURER BONNIE ARNOLD *Official Selection: 2009 Telluride Film Festival SYNOPSIS After almost fifty years of marriage, the Countess Sofya (Helen Mirren), Leo Tolstoy’s (Christopher Plummer) devoted wife, passionate lover, muse and secretary—she’s copied out War and Peace six times…by hand!—suddenly finds her entire world turned upside down. In the name of his newly created religion, the great Russian novelist has renounced his noble title, his property and even his family in favor of poverty, vegetarianism and even celibacy. After she’s born him thirteen children! When Sofya then discovers that Tolstoy’s trusted disciple, Chertkov (Paul Giamatti)—whom she despises—may have secretly convinced her husband to sign a new will, leaving the rights to his iconic novels to the Russian people rather than his very own family, she is consumed by righteous outrage. This is the last straw. Using every bit of cunning, every trick of seduction in her considerable arsenal, she fights fiercely for what she believes is rightfully hers.