“A Very Good Sailer” Merchant Ship Technology and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1502-1629 THOUGH It Did Not Take Place Until Fifteen Years Later, the Discovery of St

CHAPTER I 1502-1629 THOUGH it did not take place until fifteen years later, the discovery of St. Helena became inevitable AL when the Portuguese navigator, Bartholomew de Diaz, rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1487. For many years the Portuguese, the greatest race of sailors who ever ventured into uncharted seas, excluded from the Mediterranean, had gradually explored farther and farther along the mysterious unmapped western coast of Africa. Ten years after the epoch-making discovery of Diaz and after Columbus and Cabot had opened up the Atlantic to the races of the West and North of Europe, the King of Portugal, Emmanuel the Fortunate, sent out a fleet under the command of Vasco da Gama with orders to sail beyond the Cape of Good Hope in search of a direct sea route to India and thus tap the wealth of the East. Hitherto for centuries all trade between Europe and the East had been carried overland across Arabia, and by ship along the Mediterranean, and had been in the hands of the Italian cities of Venice and Genoa. Da Gama achieved his ambition, and arrived at Calicut, on the west coast of the Indian Peninsula, and from that day the Mediterranean, which for centuries had been the centre of civilization, began to decline. The Portuguese lost no time in building forts and setting up trading posts along the west coast of India, but their principal one was at Calicut. I 5 021 ST. HELENA ST. HELENA [1502 It is not to be wondered at that the "Moors" or Arabs who by some strange fluke of fortune, is still existing and to be for centuries had held the monopoly of the trade between found in considerable numbers. -

The Mariner's Mirror SOME ADDITIONAL NOTES CONCERNING the LE TESTU SHIPS

This article was downloaded by: [ECU Libraries] On: 23 April 2015, At: 15:44 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK The Mariner's Mirror Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rmir20 SOME ADDITIONAL NOTES CONCERNING THE LE TESTU SHIPS R. Morton Nance & L. G. Carr Laughton Published online: 22 Mar 2013. To cite this article: R. Morton Nance & L. G. Carr Laughton (1912) SOME ADDITIONAL NOTES CONCERNING THE LE TESTU SHIPS, The Mariner's Mirror, 2:3, 76-78, DOI: 10.1080/00253359.1912.10654580 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00253359.1912.10654580 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

The Poor Man's Ljungström

The poor man’s Ljungström rig (.. or how a simplified Ljungström rig can be a good alternative on a small boat...) ..by Arne Kverneland... ver. 20110722 Fredrik Ljungström: Once upon a time there lived an extraordinary man in Sweden, named Fredrik Ljungström (1875 – 1964). Like his father and brothers he turned out to be an inventor, even greater than the others. Among his over 200patents (some shared with others) the most lucrative were probably efficient steam turbines to drive electric generators and locomotives (1920) and even more important, the rotating heat regenerator which cut the coal consumption on the steam engines with over 30% (around 1930). Going through the list of patents, it is clear that he must have been a real multi-genius (.. for more info, just google Fredrik Ljungström...). The Ljungström rig – the original: Being also a keen sailor, in 1935 Mr. Ljungström came up with another brilliant idea; the Ljungström rig (Lj-rig). He had learned how dangerous it could be to handle sail on the foredeck of a small boat and his solution was radical: The diagram above of a Ljungström rig is copied from the book “RACING, CRUISING and DESIGN by Uffa Fox. (ISBN 0-907069-15-0 in UK, 0-87742-213-3 in USA). Great reading! This is a one-sail rig set on a freestanding wooden mast (.. in later designs the aft stay was omitted). The luff boltrope of the doubled sail went in a track in the mast and just as today’s roller genoas it was hoisted in spring and lowered at the end of the season. -

Northern Neck Heritage Trail Bicycling Route Network

Northern Neck Heritage Trail Bicycling Route Network Connecting People and Places Places of Interest Loop Tours Reedville-Colonial Beach Route Belle Isle State Park Located on the Rappahannock River, Dahlgren The Northern Neck Heritage Trail Bicycling Reedville and Reedville Fishermen’s Museum Walk this the park includes hiking trails, campsites (with water and Heritage Route network is a segment of the Potomac Heri- fisherman’s village and admire the stately sea captains’ electricity), a modern bath house, a guest house for over- Barnesfield Museum Park tage National Scenic Trail, a developing network homes. Learn about the Chesapeake Bay “deadrise” fish- night rental, a camp store, and kayak, canoe, bicycle and 301 ing boats and sail on an historic skipjack. Enjoy the muse- motor boat rentals. www.virginiastateparks.gov of trails between the broad, gently flowing Po- um galleries. www.rfmuseum.org Caledon Owens tomac River as it empties into the Chesapeake Menokin (c. 1769) Home of Francis Lightfoot Lee, signer State Park DAHLGREN Bay and the Allegheny Highlands in western Vir-Mar Beach A small sandy beach on the Potomac of- of the Declaration of Independence. Visitors center de- 218 fering strolling, relaxing, and birding opportunities. On picting architectural conservation, hiking trails on a 325 Pennsylvania. The “braided” Trail network offers clear days, the Smith Island Lighthouse can be seen, as acre wildlife refuge. www.menokin.org well as the shores of Maryland. www.dgif.virginia.gov/ opportunities for hiking, bicycling, paddling, Oak Crest C Mary Ball Washington Museum & Library Named in M H vbwt/siteasp?trail=1&loop=CNN&site=CNN10 A 206 Winery A horseback riding and cross-country skiing. -

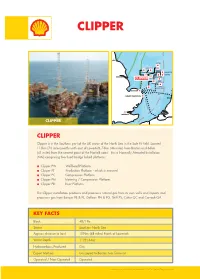

CLIPPER 021799 Asset Fact Sheets MARKETING

CLIPPER SEAL TS (BP) CA TEESSIDE CUTTER SOLE PIT CARRACK BARQUE GALLEON SHAMROCK CARAVEL EASINGTON CLIPPER BRIGANTINE CLIPPER SKIFF STANLOW INDE AMELAND INDE FIELD CORVETTE SEAN GRIJPSKERK SEAN FIELD LEMAN BACTON BBL DEN HELDER GREAT YARMOUTH BALGZAND INTERCONNECTOR EMMEN THE HAGUE SCHIEDAM LONDON CLIPPER ZEEBRUGGE CLIPPER Clipper is in the Southern part of the UK sector of the North Sea in the Sole Pit field. Located 113km (70 miles) north north east of Lowestoft, 73km (46 miles) from Bacton and 66km (41 miles) from the nearest point of the Norfolk coast. It is a Normally Attended Installation (NAI) comprising five fixed bridge linked platforms Clipper PW Wellhead Platform Clipper PT Production Platform - which is manned Clipper PC Compression Platform Clipper PM Metering / Compression Platform Clipper PR Riser Platform The Clipper installation produces and processes natural gas from its own wells and imports and processes gas from Barque PB & PL, Galleon PN & PG, Skiff PS, Cutter QC and Carrack QA. KEY FACTS Block 48/19a Sector Southern North Sea Approx distance to land 109km (68 miles) North of Lowestoft Water Depth 112ft (34m) Hydrocarbons Produced Gas Export Method Gas piped to Bacton Gas Terminal Operated / Non-Operated Operated Graphics, Media & Publication Services (Aberdeen) ITV/UZDC : Ref. 021799 January 2016 CLIPPER INFRASTRUCTURE INFORMATION Entry Specification: GSV 37-44.5MJ/sm3, Oxygen <0.2%, CO2 Max 2 mol%, H2S <3.3ppm, Total Sulphur <15ppm, WI 48-51.5 MJ/Sm3, Inerts <7%, N2 <5% Outline details of Primary separation processing -

San Francisco Public Library Historic Photograph Collection Subject Guide

San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection San Francisco History Center Subject Collection Guide S.F.P.L. HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION SUBJECT GUIDE A Adult Guidance Center AERIAL VIEWS. 1920’s 1930’s 1940’s-1980’s; 1994-1955 Agricultural Department Building A.I.D.S. Vigil. United Nations Plaza (See: Parks. United Nations Plaza) AIRCRAFT. Air Ferries Airmail Atlas Sky Merchant Coast Guard Commercial (Over S.F.) Dirigibles Early Endurance Flight. 1930 Flying Clippers Flying Clippers. Diagrams and Drawings Flying Clippers. Pan American Helicopters Light Military Military (Over S.F.) National Air Tour Over S.F. Western Air Express Airlines Building Airlines Terminal AIRLINES. Air West American British Overseas Airways California Central Canadian Pacific Century Flying A. Flying Tiger Japan Air Lines AIRLINES. Northwest Orient Pan American Qantas 1 San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection San Francisco History Center Subject Collection Guide Slick Southwest Trans World United Western AIRPORT. Administration Building. First Second. Exteriors Second. Interiors Aerial Views. Pre-1937 (See: Airport. Mills Field) Aerial Views. N.D. & 1937-1970 Air Shows Baggage Cargo Ceremonies, Dedications Coast Guard Construction Commission Control Tower Drawings, Models, Plans Fill Project Fire Fighting Equipment Fires Heliport Hovercraft International Room Lights Maintenance Millionth Passenger Mills Field Misc. Moving Sidewalk Parking Garage Passengers Peace Statue Porters Post Office Proposed Proposition No. 1 Radar Ramps Shuttlebus 2 San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection San Francisco History Center Subject Collection Guide Steamers Strikes Taxis Telephones Television Filming AIRPORT. Terminal Building (For First & Second See: Airport. Administration Building) Terminal Building. Central. Construction Dedications, Groundbreaking Drawings, Models, Plans Exteriors Interiors Terminal Building. North Terminal Building. -

Rigging Guide Viola 14 Lug Rig

Rigging Guide Viola 14 Lug Rig The Balanced Lug Rig The balanced lug rig is often chosen by small boat designers for having the following favourable characteristics: Traditional in appearance Cheap to rig Easy home construction of the spars involved Relatively short spars for a given sail area Powerful sail that is easy to control for the sail being self-vanging Very quickly to raise and to strike the sail (important for sail & oar use as well as emergencies). Good sail shape, also when reefed The lug rig is a very good choice for the Viola canoe if looking for a versatile rig that can easily be reefed, also on the water. It is excellent for touring or camp-sailing. The picture below shows the definitions used throughout this document for the various parts of a balanced lug rig. Making the Mast Mast sections are to be made of 6000 series T6 series aluminium tubes. The instructions for making the shoulder and bearings on the top mast section by using glass tape epoxied to the mast and a short section of aluminium tube of the same diameter as the bottom mast section for the shoulder (to ensure that the top mast section sits well in the bottom section) can be found in the Viola 14 plans. Dimensions/details bottom mast section: Length 2450mm Outside diameter 60mm Inside diameter 56mm (2mm wall thickness) Centre halyard cleat 550mm from the bottom of the mast. Bolt or rivet the halyard cleat to the mast. Optional saddle just above mast partner level for the dagger board elastic. -

75 the Duyfken

The Great Circle Alfons van der Kraan Vol. 35, No. 1. to return to the Netherland. This request was granted and in November 1654 he left Batavia as Vice-Admiral of the homeward bound fleet. F.W. Stapel, Hubert Hugo, een Zeerover in dienst van de Oost-Indische Compagnie, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch-Indie (BKI), Vol. 86, Parts III and IV. 86 Stapel, “Hubert Hugo, een Zeerover, op. cit., pp 618. 87 Ibid, pp. 618-19. 88 Stokram, Korte Beschrijvinge, pp. 33-35. 89 No information is available regarding the identities of these five black men. It is THE DUYFKEN: AN EXPLORATION OF THE ROLES OF A not certain, therefore, whether these men were disgruntled members of Captain Hugo’s crew or runaway slaves. The latter assumption is not unreasonable REPLICA SHIP because the L’Aigle Noir was heading for the West Indies where, largely on account of the rapidly expanding sugar industry, there was a big market for African slaves. On 11 January 2012, in a press release headed ‘“Little Dove’” to 90 J. A. van der Chijs (ed.), Daghregister gehouden in ‘t Casteel Batavia, 1661 return home to WA’, Western Australia’s Deputy Premier and Minister and 1663, M. Nijhoff, Den Haag, 1891, pp. 422-24. for Tourism, Kim Hames, announced that the Duyfken1606 Replica 91 Cort Verhael door de Opperhoofden van ‘t Schip Aernhem wegens haer wedervaren en verongelucken van voormelte schip, 24-6-1662, Nationaal Foundation would receive government support to bring the Duyfken Archief, Company 1239, fol. 1230. replica back to the state. -

Dictionary.Pdf

THE SEAFARER’S WORD A Maritime Dictionary A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ranger Hope © 2007- All rights reserved A ● ▬ A: Code flag; Diver below, keep well clear at slow speed. Aa.: Always afloat. Aaaa.: Always accessible - always afloat. A flag + three Code flags; Azimuth or bearing. numerals: Aback: When a wind hits the front of the sails forcing the vessel astern. Abaft: Toward the stern. Abaft of the beam: Bearings over the beam to the stern, the ships after sections. Abandon: To jettison cargo. Abandon ship: To forsake a vessel in favour of the life rafts, life boats. Abate: Diminish, stop. Able bodied seaman: Certificated and experienced seaman, called an AB. Abeam: On the side of the vessel, amidships or at right angles. Aboard: Within or on the vessel. About, go: To manoeuvre to the opposite sailing tack. Above board: Genuine. Able bodied seaman: Advanced deckhand ranked above ordinary seaman. Abreast: Alongside. Side by side Abrid: A plate reinforcing the top of a drilled hole that accepts a pintle. Abrolhos: A violent wind blowing off the South East Brazilian coast between May and August. A.B.S.: American Bureau of Shipping classification society. Able bodied seaman Absorption: The dissipation of energy in the medium through which the energy passes, which is one cause of radio wave attenuation. Abt.: About Abyss: A deep chasm. Abyssal, abysmal: The greatest depth of the ocean Abyssal gap: A narrow break in a sea floor rise or between two abyssal plains. -

A „Szőke Tisza” Megmentésének Lehetőségei

A „SZŐKE TISZA” MEGMENTÉSÉNEK LEHETŐSÉGEI Tájékoztató Szentistványi Istvánnak, a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnökének Összeállította: Dr. Balogh Tamás © 2012.03.27. TIT – Hajózástörténeti, -Modellező és Hagyományőrző Egyesület 2 TÁJÉKOZTATÓ Szentistványi István, a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnöke részére a SZŐKE TISZA II. termesgőzössel kapcsolatban 2012. március 27-én Szentistványi István a szegedi Városkép- és Környezetvédelmi Bizottság elnöke e-mailben kért tájékoztatást Dr. Balogh Tamástól a TIT – Hajózástörténeti, -Modellező és Hagyományőrző Egyesület elnökétől a SZŐKE TISZA II. termesgőzössel kapcsolatban, hogy tájékozódjon a hajó megmentésének lehetőségéről – „akár jelentősebb anyagi ráfordítással, esetleges városi összefogással is”. A megkeresésre az alábbi tájékoztatást adom: A hajó 2012. február 26-án süllyedt el. Azt követően egyesületünk honlapján – egy a hajónak szentelt tematikus aloldalon – rendszeresen tettük közzé a hajóra és a mentésére vonatkozó információkat, képeket, videókat (http://hajosnep.hu/#!/lapok/lap/szoke-tisza-karmentes), amelyekből szinte napi ütemezésben nyomon követhetők a február 26-március 18 között történt események. A honlapon elérhető információkat nem kívánom itt megismételni. Egyebekben a hajó jelentőségéről és az esetleges városi véleménynyilvánítás elősegítésére az alábbiakat tartom szükségesnek kiemelni: I) A hajó jelentősége: Bár a Kulturális Örökségvédelmi Hivatal előtt jelenleg zajlik a hajó örökségi védelembe vételére irányuló eljárás (a hajó örökségi -

Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf

OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Gulf of Mexico OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Author TRC Environmental Corporation Prepared under BOEM Contract M08PD00024 by TRC Environmental Corporation 4155 Shackleford Road Suite 225 Norcross, Georgia 30093 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management New Orleans Gulf of Mexico OCS Region May 2012 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and TRC Environmental Corporation. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endoresements or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY This report is available only in compact disc format from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, at a charge of $15.00, by referencing OCS Study BOEM 2012-008. The report may be downloaded from the BOEM website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report also from the National Technical Information Service in the near future. Here are the addresses. You may also inspect copies at selected Federal Depository Libraries. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. -

SEA8 Techrep Mar Arch.Pdf

SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Report prepared by: Maritime Archaeology Ltd Room W1/95 National Oceanography Centre Empress Dock Southampton SO14 3ZH © Maritime Archaeology Ltd In conjunction with: Dr Nic Flemming Sheets Heath, Benwell Road Brookwood, Surrey GU23 OEN This document was produced as part of the UK Department of Trade and Industry's offshore energy Strategic Environmental Assessment programme. The SEA programme is funded and managed by the DTI and coordinated on their behalf by Geotek Ltd and Hartley Anderson Ltd. © Crown Copyright, all rights reserved Document Authorisation Name Position Details Signature/ Initial Date J. Jansen van Project Officer Checked Final Copy J.J.V.R 16 April 07 Rensburg G. Momber Project Specialist Checked Final Copy GM 18 April 07 J. Satchell Project Manager Authorised final J.S 23 April 07 Copy Maritime Archaeology Ltd Project No 1770 2 Room W1/95, National Oceanography Centre, Empress Dock, Southampton. SO14 3ZH. www.maritimearchaeology.co.uk SEA8 Technical Report – Marine Archaeological Heritage ______________________________________________________________ Contents I LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................5 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................7 1. NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY................................................................................8 1.1