Jorge Luis Borges: a Study of Criticism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dearth and Duality: Borges' Female Fictional Characters

DEARTH AND DUALITY: BORGES' FEMALE FICTIONAL CHARACTERS When studying Borges' fiction, the reader is immediately struck by the dear_th of female characters or love interest. Borges, who has often been questioned about this aspect of his work confided to Gloria Alcorta years ago: "alors si je n 'ecris pas sur ses sujects, c 'est simplememnt par·pudeur ... sans doute ai-je-ete trop ocupe par l'amour dans rna vie privee pour en parler dans roes livres."1 At the age of eighty, when questioned by Coffa, Borges said: "If I have created any character, I don't think so, I am always writing about myself ... It is always the same old Borges, only slightly disguised. "2 Many critics have decried lack of female characters and character development. Alicia Jurado likens Borges to a stage director who uses women as one would furniture or sets, in order to create environment. She says:" son borrosos o casuales o lo minimo indiferenciadas y pasi vas. "3 E.D. Carter calls Borges' women little more than abstractions or symbolic interpretations.4 Picknhayn says that Borges' women "aparecen distorsionadas ... hasta el punto de transformar cada mujer en una cosa amorfa y carente de personalidad. " 5 and Lloyd King feels that the women of Borges' stories "always at best seem instrumental. "6 All of the above can be said of most of his male characters because none of Borges' characters can be classified in the traditional sense. A Vilari or Hladik is no more real than a Beatriz or Ulrica. Juan Otalora is no more real than la Pelirroja and Red Scharlach is no more real than Emma Zunz. -

Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Kevin Wilson Of Stones and Tigers; Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Pu Songling (1640-1715) (draft) The need to meet stones with tigers speaks to a subtlety, and to an experience, unique to literary and conceptual analysis. Perhaps the meeting appears as much natural, even familiar, as it does curious or unexpected, and the same might be said of meeting Pu Songling (1640-1715) with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), a dialogue that reveals itself as much in these authors’ shared artistic and ideational concerns as in historical incident, most notably Borges’ interest in and attested admiration for Pu’s work. To speak of stones and tigers in these authors’ works is to trace interwoven contrapuntal (i.e., fugal) themes central to their composition, in particular the mutually constitutive themes of time, infinity, dreaming, recursion, literature, and liminality. To engage with these themes, let alone analyze them, presupposes, incredibly, a certain arcane facility in navigating the conceptual folds of infinity, in conceiving a space that appears, impossibly, at once both inconceivable and also quintessentially conceptual. Given, then, the difficulties at hand, let the following notes, this solitary episode in tracing the endlessly perplexing contrapuntal forms that life and life-like substances embody, double as a practical exercise in developing and strengthening dynamic “methodologies of the infinite.” The combination, broadly conceived, of stones and tigers figures prominently in -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Dragonlore Issue 37 08-11-03

The bird was a Rukh and the white dome, of course, was its egg. Sindbad lashes himself to the bird’s leg with his turban, and the next morning is whisked off into flight and set down on a mountaintop, without having excited the Rukh’s attention. The narrator adds that the Rukh feeds itself on serpents of such great bulk that they would have made but one gulp of an elephant. In Marco Polo’s Travels (III, 36) we read: Dragonlore The people of the island [of Madagascar] report that at a certain season of the year, an extraordinary kind of bird, which they call a rukh, makes its appearance from The Journal of The College of Dracology the southern region. In form it is said to resemble the eagle but it is incomparably greater in size; being so large and strong as to seize an elephant with its talons, and to lift it into the air, from whence it lets it fall to the ground, in order that when dead it Number 37 Michaelmas 2003 may prey upon the carcase. Persons who have seen this bird assert that when the wings are spread they measure sixteen paces in extent, from point to point; and that the feathers are eight paces in length, and thick in proportion. Marco Polo adds that some envoys from China brought the feather of a Rukh back to the Grand Kahn. A Persian illustration in Lane shows the Rukh bearing off three elephants in beak and talons; ‘with the proportion of a hawk and field mice’, Burton notes. -

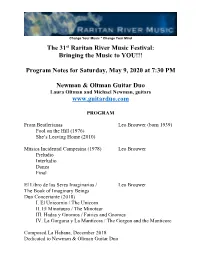

Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman

Change Your Music * Change Your Mind The 31st Raritan River Music Festival: Bringing the Music to YOU!!! Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Laura Oltman and Michael Newman, guitars www.guitarduo.com PROGRAM From Beatlerianas Leo Brouwer (born 1939) Fool on the Hill (1976) She’s Leaving Home (2010) Música Incidental Campesina (1978) Leo Brouwer Preludio Interludio Danza Final El Libro de los Seres Imaginarios / Leo Brouwer The Book of Imaginary Beings Duo Concertante (2018) I. El Unicornio / The Unicorn II. El Minotauro / The Minotaur III. Hadas y Gnomos / Fairies and Gnomes IV. La Gorgona y La Mantícora / The Gorgon and the Manticore Composed La Habana, December 2018 Dedicated to Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Commissioned by Raritan River Music With the generous support of Jeffrey Nissim CYBERSPACE PERMIERE PERFORMANCE Composed in celebration of the 80th Anniversary Year of Leo Brouwer NOTES IN ENGLISH CAPTURING THE IMAGINARY BEINGS BY LAURA OLTMAN AND MICHAEL NEWMAN The guitar explosion in the United States in the 1960s was fueled by the influence of Cuban musicians, including the legendary Leo Brouwer, as well as Juan Mercadal, Elías Barreiro, Mario Abril, and our teachers Alberto Valdes Blain and Luisa Sánchez de Fuentes. We grew up playing the music of Leo Brouwer. In the early days of the Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo, we shared a booking agent with Brouwer, Sheldon Soffer Management. We often thought that a major duet by Maestro Brouwer would be a dream for our duo. We met Brouwer at his New York debut recital in 1978, which was co- sponsored by Americas Society. -

Farmerfan Volume 1 | Issue 1 |July 2018

FarmerFan Volume 1 | Issue 1 |July 2018 FarmerCon 100 / PulpFest 2018 Debut Issue Parables in Parabolas: The Role of Mainstream Fiction in the Wold Newton Mythos by Sean Lee Levin The Wold Newton Family is best known for its crimefighters, detectives, and explorers, but less attention has been given to the characters from mainstream fiction Farmer included in his groundbreaking genealogical research. The Swordsmen of Khokarsa by Jason Scott Aiken An in-depth examination of the numatenu from Farmer’s Ancient Opar series, including speculations on their origins. The Dark Heart of Tiznak by William H. Emmons The extraterrestrial origin of Philip José Farmer's Magic Filing Cabinet revealed. Philip José Farmer Bingo Card by William H. Emmons Philip José Farmer Pulp Magazine Bibliography by Jason Scott Aiken About the Fans/Writers Visit us online at FarmerFan.com FarmerFan is a fanzine only All articles and material are copyright 2018 their respective authors. Cover photo by Zacharias L.A. Nuninga (October 8, 2002) (Source: Wikimedia Commons) Parables in Parabolas The Role of Mainstream Fiction in the Wold Newton Mythos By Sean Lee Levin The covers to the 2006 edition of Tarzan: Alive and the 2013 edition of Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life Parables travel in parabolas. And thus present us with our theme, which is that science fiction and fantasy not only may be as valuable as the so-called mainstream of literature but may even do things that are forbidden to it. –Philip José Farmer, “White Whales, Raintrees, Flying Saucers” Of all the magnificent concepts put to paper by Philip José Farmer, few are as ambitious as his writings about the Wold Newton Family. -

In “Death and the Compass” Borges Presciently Anticipates De

SYMMETRY OF DEATH w Adrian Gargett n “Death and the Compass” Borges presciently anticipates de- velopments in contemporary physics and scientific thought, I constructing a literary environment that systemically gives the lie t o the dream of rational determinism, suggesting instead some- thing like a “primordial disorder” out of which the shifting, provi- sional orders of culture and science emerge. In constructing a subtle and complex argument via the parallel in- teractions of a Deleuzo-guattarian mechanism, this project artfully attempts to weave the principal discursive strands into an animated investigative framework. The first strand is a close analysis of sections from “Death and the Compass”. The second is the articulation of the critical concepts from the Deleuzo-guattarian scheme. The third is the embedding of the issues of chance and causality within the work of Borges. J (NORTH) The first murder occurred in the Hotel du Nord – that tall prism which dominates the estuary whose waters are the colour of the de- sert. To that tower (which quite glaringly unifies the hateful white- ness of a hospital, the numbered divisibility of a jail and the general Variaciones Borges 13 (2002) 80 ADRIAN GARGETT appearance of a bordello) there came on the third day of December the delegate from Podolsk to the Third Talmudic Congress, Doctor Marcel Yarmolinsky, a grey-bearded man with grey eyes. (Labyrinths 106) Deleuze and Guattari cast literature as an exemplary mode to demonstrate systems of machinic functioning; how litera- ture/books/writing operates in terms of such functioning – in terms of a “rhizomatic” analysis as presented in “A Thousand Plateaus”.1 Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic conceptual vehicle maps a schizoanalytic application to Borges disseminating literary texts. -

Poetics of Enchantment: Language, Sacramentality, and Meaning in Twentieth-Century Argentine Poetry

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2011 POETICS OF ENCHANTMENT: LANGUAGE, SACRAMENTALITY, AND MEANING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ARGENTINE POETRY Adam Gregory Glover University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Glover, Adam Gregory, "POETICS OF ENCHANTMENT: LANGUAGE, SACRAMENTALITY, AND MEANING IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY ARGENTINE POETRY" (2011). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 3. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/3 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. -

Ge Fei's Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges's Narrative Labyrinth

Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. DOI 10.1007/s40647-015-0083-x ORIGINAL PAPER Imitation and Transgression: Ge Fei’s Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges’s Narrative Labyrinth Qingxin Lin1 Received: 13 November 2014 / Accepted: 11 May 2015 © Fudan University 2015 Abstract This paper attempts to trace the influence of Jorge Luis Borges on Ge Fei. It shows that Ge Fei’s stories share Borges’s narrative form though they do not have the same philosophical premises as Borges’s to support them. What underlies Borges’s narrative complexity is his notion of the inaccessibility of reality or di- vinity and his understanding of the human intellectual history as epistemological metaphors. While Borges’s creation of narrative gap coincides with his intention of demonstrating the impossibility of the pursuit of knowledge and order, Ge Fei borrows this narrative technique from Borges to facilitate the inclusion of multiple motives and subject matters in one single story, which denotes various possible directions in which history, as well as story, may go. Borges prefers the Jungian concept of archetypal human actions and deeds, whereas Ge Fei tends to use the Freudian psychoanalysis to explore the laws governing human behaviors. But there is a perceivable connection between Ge Fei’s rejection of linear history and tradi- tional storyline with Borges’ explication of epistemological uncertainty, hence the former’s tremendous debt to the latter. Both writers have found the conventional narrative mode, which emphasizes the telling of a coherent story having a begin- ning, a middle, and an end, inadequate to convey their respective ideational intents. -

1 Jorge Luis Borges the GOSPEL ACCORDING to MARK

1 Jorge Luis Borges THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO MARK (1970) Translated by Norrnan Thomas di Giovanni in collaboration with the author Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), an outstanding modern writer of Latin America, was born in Buenos Aires into a family prominent in Argentine history. Borges grew up bilingual, learning English from his English grandmother and receiving his early education from an English tutor. Caught in Europe by the outbreak of World War II, Borges lived in Switzerland and later Spain, where he joined the Ultraists, a group of experimental poets who renounced realism. On returning to Argentina, he edited a poetry magazine printed in the form of a poster and affixed to city walls. For his opposition to the regime of Colonel Juan Peron, Borges was forced to resign his post as a librarian and was mockingly offered a job as a chicken inspector. In 1955, after Peron was deposed, Borges became director of the national library and Professor of English Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. Since childhood a sufferer from poor eyesight, Borges eventually went blind. His eye problems may have encouraged him to work mainly in short, highly crafed forms: stories, essays, fables, and lyric poems full of elaborate music. His short stories, in Ficciones (1944), El hacedor (1960); translated as Dreamtigers, (1964), and Labyrinths (1962), have been admired worldwide. These events took place at La Colorada ranch, in the southern part of the township of Junin, during the last days of March 1928. The protagonist was a medical student named Baltasar Espinosa. We may describe him, for now, as one of the common run of young men from Buenos Aires, with nothing more noteworthy about him than an almost unlimited kindness and a capacity for public speaking that had earned him several prizes at the English school0 in Ramos Mejia. -

Postmodern Or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation

Edna Aizenberg Postmodern or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation he list of “firsts” is well known by now: Borges, father of the New Novel, the nouveau roman, the Boom; Borges, forerunner T of the hypertext, early magical realist, proto-deconstructionist, postmodernist pioneer. The list is well known, but it may omit the most significant encomium: Borges, founder of literature after Auschwitz, a literature that challenges our orders of knowledge through the frac- tured mirror of one of the century’s defining events. Fashions and prejudices ingrained in several critical communities have obscured Borges’s role as a passionate precursor of many later intellec- tuals -from Weisel to Blanchot, from Amery to Lyotard. This omission has hindered Borges research, preventing it from contributing to major theoretical currents and areas of inquiry. My aim is to confront this lack. I want to rub Borges and the Holocaust together in order to unset- tle critical verities, meditate on the limits of representation, foster dia- logue between disciplines -and perhaps make a few sparks fly. A shaper of the contemporary imagination, Borges serves as a touch- stone for concepts of literary reality and unreality, for problems of knowledge and representation, for critical and philosophical debates on totalizing systems and postmodern esthetics, for discussions on cen- ters and peripheries, colonialism and postcolonialism. Investigating the Holocaust in Borges can advance our broadest thinking on these ques- tions, and at the same time strengthen specific disciplines, most par- ticularly Borges scholarship, Holocaust studies, and Latin American literary criticism. It is to these disciplines that I now turn. -

Perspectives on Borges' Library of Babel

Proceedings of Bridges 2015: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Perspectives on Borges' Library of Babel CJ Fearnley Jeannie Moberly [email protected] [email protected] http://blog.CJFearnley.com http://Moberly.CJFearnley.com 240 Copley Road • Upper Darby, PA 19082 240 Copley Road • Upper Darby, PA 19082 Abstract This study builds on our Bridges 2012 work on Harmonic Perspective. Jeannie’s artwork explores 3D spaces with an intersecting plane construction. We used the subject of the remarkable “Universe (which others call the Library)” of Jorge Luis Borges. Our study explores the use of harmonic sequences and nets of rationality. We expand on our prior use of harmonics in Apollonian circles to a pencil of nonintersecting circles. Using matrix distortion and ambiguous direction in the multiple dimensions of a spiral staircase in the Library we break from harmonic measurements. We wonder about the contrasting perspectives of unimaginable finiteness and infiniteness. Figure 1 : Borges' Library of Babel (View of Apollonian Ventilation Shafts). Figure 2 : Borges' Library of Babel (Other View). Introduction In 1941, Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) published a short story The Library of Babel [2] that has intrigued artists, mathematicians, and philosophers ever since. The story plays with ideas of infinity, the very large but finite, the components of immensity, and periodicity. The Library consists of a vast number of hexagonal rooms each with the same number of books. Although each book is unique, each has the same number 443 Fearnley and Moberly of pages, lines, and characters. The librarians wander their whole lives through the labyrinth of rooms wondering about the nature of their Universe.