Anton Pannekoek's Understanding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Róber Iturriet Ávila ■ Castor Bartolomé Ruiz ■ Bruno Lima Rocha EDITORIAL

Nº 521 | Ano XVIII | 7/5/2018 1968 – um ano múltiplo Meio século de um tempo que desafiou diversas formas de poder Patrick Viveret Glaudionor Barbosa Enéas de Souza Larissa Jacheta Riberti Erick Corrêa Joana Salém Maria Paula Araújo Olgária Matos Alana Moraes de Souza Leia também ■ Róber Iturriet Ávila ■ Castor Bartolomé Ruiz ■ Bruno Lima Rocha EDITORIAL 1968 – um ano múltiplo Meio século de um tempo que desafiou diversas formas de poder uando se fala em 1968, parece que se porque explodiram revoltas de jovens, de artis- trata de algo uno, um acontecimento tas e do operariado em vários lugares do mundo. coeso. No entanto, o mais correto seria Para a antropóloga Alana Moraes de Sou- Qaludir aos vários 1968, ocorridos em geografias za, Maio de 68 – marcante para a história das e contextos tão distintos como a França, a Tche- contestações ao capitalismo e às estruturas au- coslováquia, os Estados Unidos, o México, o toritárias – não foi superado, nem derrotado. Brasil e outros países latino-americanos. Ela diz que as lutas vão sedimentando substra- O ano de 1968 é múltiplo de sentidos, signi- tos, e toda vez que a sociedade se movimenta, de ficados e alcances. Na base da efervescência, algum modo os substratos emergem. estão as rebeliões estudantis e de trabalhadores O cientista político Glaudionor Barbosa que inflamaram ruas e desafiaram diversas for- vislumbra que é preciso consolidar uma narra- mas de poder. Chefes de Estado, ditadores, em- tiva de 1968 que aponte para um futuro melhor presários, reitores, professores e as tradicionais do que o presente. estruturas familiares, sindicais e partidárias – todos foram questionados e tensionados. -

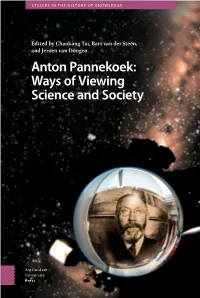

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Chaulieu's Response to Pannekoek's Second and Third Letters*

Chaulieu’s Response to Pannekoek’s Second and Third Letters* Paris, August 22, 1954 Dear Comrade Pannekoek, Please excuse my somewhat tardy response to your letter of June 15; I was absent from Paris and wanted to answer you only after discussing it with the comrades from our group. In the meantime, I also received your letter of August 10,1 with the article on Marxist “ethics,”2 which we also discussed. Concerning your letter of June 15, we have unanimously decided to publish it in the upcoming issue (15)3 of “Socialisme ou Barbarie.” It certainly will help readers to understand your point of view better, both on the party question and on that of the character of the Russian Revolution. For my part, I do not think that I personally have anything of importance to add to what I wrote in issue 14. To you alone I would like to point out that I have never thought that “we can defeat the CP . by copying its methods” and that I have always said that the working class—or its vanguard —needed a new mode of organization, one that meets the needs of the struggle against the bureaucracy, not only the outside and already attained bureaucracy (that of the CP) but also the potential bureaucracy from within. I am saying: The working class needs an organization before *Editor: This letter is available in box 11 of the Antonie Pannekoek Archives: see: http://www.aaap.be/Pdf/IISG-Archief-Pannekoek/Map-011.pdf for the scan. We have on occasion consulted an earlier, partial translation, available in Marcel van der Linden’s “Did Castoriadis Suppress a Letter from Pannekoek? A Note on the Debate regarding the ‘Organizational Question’ in the 1950s,” A Usable Collection: Essays in Honour of Jaap Kloosterman on Collecting Social History, ed. -

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Tai, C.; van der Steen, B.; van Dongen, J. DOI 10.2307/j.ctvp7d57c 10.1515/9789048535002 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tai, C., van der Steen, B., & van Dongen, J. (Eds.) (2019). Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society. (Studies in the History of Knowledge). Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvp7d57c, https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048535002 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. -

170615 a Free Retriever's Digest.Try-Out Nr 03

A Free Retriever's Digest "n interested Se ection of "rti! es # Ne%s Feeds Try-out Issue #3 June 15, 2017 Contents From the Editor (2) Se e!ted "rti! es # $e%s Feeds (3) May 15 – June 11, 2017 (week no.’s 20 – 23) "n In&it'tion to ' (e)'te (*) October Revolut!on 1917: $oes Marx!sm ea' to (tate )error aga!nst the ,ork!n* - ass. E+,ress- $e% .'m,h ets (/) • G.I.S.: 1"21 – )+e (tart of t+e -ounter0revo ut!on (") • Nelke: - ass (tru** es !n t+e 1.R.$. (1"25 – 1"3") 4resentat!on of 5o u&e 6. (") To,i!- 0'r+ 'nd the 1uestion o2 the St'te (11) Ma% 7e&8e (1927) or: Marx an' 9nge s versus Len!n’s ‘State and Revolution’ • 1!o*ra8+!ca ;ote# Jan <88e (13"0 – May 2, 1"35) (13) 1uoted- $'tion or C 'ss3 (14) =Aurora’ (I.-.).) on a choice the historical situation imposes upon the proletariat 1uoted- 5.ro et'rios Intern'!ion' ist's6 (17) 5ene>ue a# 4opu ar 4ower an' (oc!a !sm !n the 21st -entury – The Modern Clothes of Social !emocrac" Indi8esti) e- 9ine8'r so d 's :ine (1*) )+e (u88ort /or <nti0/asc!sm by a ?rou8 ay!ng c a!& to -ounc! -om&un!sm Last updated: 16. June 2017 2 " Free Retriever<s Digest From the Editor Friday, June 16, 2017 =>S> With the third try-out issue of this Digest, this project takes a somewhat more concrete shape. -

The Dutch and German Communist Left (1900–68) Historical Materialism Book Series

The Dutch and German Communist Left (1900–68) Historical Materialism Book Series Editorial Board Sébastien Budgen (Paris) David Broder (Rome) Steve Edwards (London) Juan Grigera (London) Marcel van der Linden (Amsterdam) Peter Thomas (London) volume 125 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hm The Dutch and German Communist Left (1900–68) ‘Neither Lenin nor Trotsky nor Stalin!’ ‘All Workers Must Think for Themselves!’ By Philippe Bourrinet leiden | boston This work is a revised and English translation from the Italian edition, entitled Alle origini del comunismo dei consigli. Storia della sinistra marxista olandese, published by Graphos publishers in Genoa in 1995. The Italian edition is again a revised version of the author’s doctorates thesis presented to the Université de Paris i in 1988. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1570-1522 isbn 978-90-04-26977-4 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32593-7 (e-book) Copyright 2017 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill nv provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, ma 01923, usa. -

Karl Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy (Translated by Fred Halliday, Monthly Review Press, 1970 and 2008)

Cutrone, Book review: Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy (9/3/09) 1/12 Book review: Karl Korsch, Marxism and Philosophy (translated by Fred Halliday, Monthly Review Press, 1970 and 2008) Chris Cutrone [Marx wrote,] “[Humanity] always sets itself only such problems as it can solve; since, looking at the matter more closely it will always be found that the problem itself arises only when the material conditions for its solution are already present or are at least understood to be in the process of emergence.”1 This dictum is not affected by the fact that a problem which supersedes present relations may have been formulated in an anterior epoch. As scientific socialism, the Marxism of Marx and Engels remains the inclusive whole of a theory of social revolution . a materialism whose theory comprehended the totality of society and history, and whose practice overthrew it. The difference [now] is that the various components of [what for Marx and Engels was] the unbreakable interconnection of theory and practice are further separated out. The umbilical cord has been broken. — Karl Korsch, “Marxism and Philosophy” (1923) The problem of “Marxism and Philosophy” — Korsch and Adorno on theory and practice KARL KORSCH’S SEMINAL ESSAY “Marxism and Philosophy” (1923) was first published in English, translated by Fred Halliday, in 1970 by Monthly Review Press. In 2008, they reprinted the volume, which also contains some important shorter essays, as part of their new “Classics” series. The original publication of Korsch’s essay coincided with Georg Lukács’s 1923 landmark collection of essays, History and Class Consciousness (HCC). -

Technoscience Comes with Millenarian Overtones

Editors’ Introduction Talk of technoscience comes with millenarian overtones. In some current usages in the interdisciplinary field of science and technology studies (STS), claims about the close alliance of systems of knowledge production, technical control, and trans- national capital are mixed up with versions of an imminent future of decentered, networked, and distributed capacities and visionary possibilities across species and across natures. But the eschatology of those who first introduced the term into English was initially much darker. Technoscience as a concept appeared at the start of the Cold War. In early 1946, the Yale law professor and military propaganda expert Harold Lasswell wrote of modern science and technology as a Western Euro- pean monopoly whose universalization, even if temporarily blocked by the bipolar politics of US- Soviet rivalry, would inevitably subject the world to the rule of the machine, “a condensed way of referring to the modern techno- scientific complex.” Lasswell commended Werner Sombart’s ferociously anti- Marxist writings on prole- tarian socialism as a guide to how encounter with technoscience would dynamize “the traditional outlook of any culture,” however “supine.”1 Technoscience thus became a commonplace index for the allegedly inevi- table system of modern capitalist industrialization, its mobilization of scientific and technical expertise, and, decisively, its military- economic dominance. Those who bemoaned scientists’ enlistment in the bureaucracies and testing grounds of the military- industrial complex, or who reckoned that scientific virtue might just be able to resist such enlistment, used the term technoscience to describe the threat. By the late 1950s, the word was linked directly to thermonuclear extermination. -

Connecting the Scientific and Socialist Virtues of Anton Pannekoek

CHAOKANG TAI* Left Radicalism and the Milky Way: Connecting the Scientific and Socialist Virtues of Anton Pannekoek ABSTRACT Anton Pannekoek (1873–60) was both an influential Marxist and an innovative astronomer. This paper will analyze the various innovative methods that he developed to represent the visual aspect of the Milky Way and the statistical distribution of stars in the galaxy through a framework of epistemic virtues. Doing so will not only emphasize the unique aspects of his astronomical research, but also reveal its connections to his left radical brand of Marxism. A crucial feature of Pannekoek’s astronomical method was the active role ascribed to astronomers. They were expected to use their intuitive ability to organize data according to the appearance of the Milky Way, even as they had to avoid the influence of personal experience and theoretical presuppositions about the shape of the system. With this method, Pannekoek produced results that went against the Kapteyn Universe and instead made him the first astronomer in the Netherlands to find supporting evidence for Harlow Shapley’s extended galaxy. After exploring Pannekoek’s Marxist philosophy, it is argued that both his astronomical method and his interpretation of historical materialism can be seen as strategies developed to make optical use of his particular conception of the human mind. *Institute for Theoretical Physics Amsterdam, Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, and Vossius Center for History of Humanities and Sciences, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904,POBox94485, -

4 Utopianism in Anton Pannekoek's Socialism and Astronomy

4 Utopianism in Anton Pannekoek’s Socialism and Astronomy Klaas van Berkel Abstract During World War II, Anton Pannekoek wrote two separate memoirs, one about his life in astronomy, another about his life in the socialist movement. Historians have often wondered what the deeper unity behind these two different accounts of Pannekoek’s life may have been. Here it is claimed that the answer is utopianism. Pannekoek encountered utopianism in the work of the American novelist Edward Bellamy and this utopianism strongly resonated with the ideas of the socialist thinker Joseph Dietzgen, who was much admired by Pannekoek. Careful reading of the memoirs reveals that the ideal of purity, so common around the turn of the nineteenth century, was common to both Bellamy’s picture of future society in Boston and Dietzgen’s and Pannekoek’s ideas about how to arrive at the socialist state. Keywords: Anton Pannekoek, Utopianism, two cultures, Edward Bellamy, Joseph Dietzgen, purity During the last, dark winter of World War II, Anton Pannekoek wrote two separate autobiographies, one on his involvement in the socialist movement, the other dealing with his career in astronomy.1 By completely separating his scientific and his socialist memoirs, Pannekoek suggested that his work in astronomy was totally unrelated to his work in politics. On reading the This contribution is a revised version of a presentation at the annual General Meeting of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1999. Present at that meeting was Anton Pannekoek’s son, the geologist Antonie Johannes (Ton) Pannekoek (1905-2000), who in general agreed with my interpretation of the life and work of his father. -

Critical Theory As Radical Crisis Theory: Kurz, Krisis, and Exit! on Value Theory, the Crisis, and the Breakdown of Capitalism

Rethinking Marxism A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society ISSN: 0893-5696 (Print) 1475-8059 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrmx20 Critical Theory as Radical Crisis Theory: Kurz, Krisis, and Exit! on Value Theory, the Crisis, and the Breakdown of Capitalism Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Dominique Routhier To cite this article: Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen & Dominique Routhier (2019) Critical Theory as Radical Crisis Theory: Kurz, Krisis, and Exit on Value Theory, the Crisis, and the Breakdown of Capitalism, Rethinking Marxism, 31:2, 173-193, DOI: 10.1080/08935696.2019.1592408 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2019.1592408 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rrmx20 RETHINKING MARXISM, 2019 Vol. 31, No. 2, 173–193, https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2019.1592408 Critical Theory as Radical Crisis Theory: Kurz, Krisis, and Exit! on Value Theory, the Crisis, and the Breakdown of Capitalism Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen and Dominique Routhier The essay introduces the work of Robert Kurz and the somewhat marginalized species of value critique that he is associated with: Wertkritik. On the basis of a critical historiographical account of the “New Marx Reading,” it argues that the theoretical and political differences between Wertkritik and other value-critical currents cannot be glossed over or dismissed as mere territorial strife but must instead be understood as an expression of a more fundamental disagreement about the nature of capitalism and the role of “critique,” the distinctive feature of course being the insistence on a proper theory of crisis. -

Workers Councils Online

1iPIM [Read now] Workers Councils Online [1iPIM.ebook] Workers Councils Pdf Free Anton Pannekoek *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1279200 in Books Anton Pannokoek 2010-09-23Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.50 x .66 x 5.50l, .75 #File Name: 1453716270292 pagesWorkers Councils | File size: 59.Mb Anton Pannekoek : Workers Councils before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Workers Councils: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. A very important work in MarxismBy Sid BarretThis rare work is a must to anyone interested in Marxist theory. Workers Councils shows the corruption and depravity in both Western Capitalism and Soviet "Socialism". Other works on Libertarian Socialism that I would recommend would be Rosa Luxemburg Speaks,Moving Forward: Program for a Participatory Economy, Socialism: Past and Future,My disillusionment in Russia0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. this is a good book if youre interested in the practical aspects of ...By CityChickenthis is a good book if youre interested in the practical aspects of worker's power but it can be a bit dry. the edition you see above has several interesting interviews as well.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Excellent workBy Double DubsOne of the lesser known groups sitting under the "communist" label is that of the Council Communists. These were the ones who regularly critiqued the lack of workers power in the USSR once it became evident that power had been stripped from them.