Assessment Report on the Legal and Administrative Implementation of the Bern Convention in Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Results Regarding the Rock Falls of December 17, 2009 at Tempi, Greece

Bulletin of the Geological Soci- Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής ety of Greece, 2010 Εταιρίας, 2010 Proceedings of the 12th Interna- Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρί- tional Congress, Patras, May, ου, Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 2010 PRELIMINARY RESULTS REGARDING THE ROCK FALLS OF DECEMBER 17, 2009 AT TEMPI, GREECE Christaras B.1, Papathanassiou G.1, Vouvalidis K.2, Pavlides S.1 1 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Geology, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Physical and Environmental Geography, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece, [email protected] Abstract On December 17, 2009, a large size rock fall generated at the area of Tempi, Central Greece causing one casualty. In particular, a large block was detached from a high of 70 meters and started to roll downslope and gradually became a rock slide. About 120 tones of rock material moved downward to the road resulting to the close of the national road. Few days after the slope failure, a field survey organized by the Department of Geology, AUTH took place in order to evaluate the rock fall hazard in the area and to define the triggering causal factors. As an out- come, we concluded that the heavily broken rock mass and the heavy rain-falls, of the previous days, contribute significantly to the generation of the slope failure. The rocky slope was limited stable and the high joint water pressure caused the failure of the slope. Key words: rock fall, Tempi, engineering geology, hazard, Greece 1. Introduction A rock fall is a fragment of rock detached by sliding, toppling or falling that falls along a vertical or sub-vertical cliff, proceeds down slope by bouncing and flying along ballistic trajectories or by rolling on talus or debris slopes (Varnes, 1978). -

Grand Tour of Greece

Grand Tour of Greece Day 1: Monday - Depart USA Depart the USA to Greece. Your flight includes meals, drinks and in-flight entertainment for your journey. Day 2: Tuesday - Arrive in Athens Arrive and transfer to your hotel. Balance of the day at leisure. Day 3: Wednesday - Tour Athens Your morning tour of Athens includes visits to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Panathenian Stadium, the ruins of the Temple of Zeus and the Acropolis. Enjoy the afternoon at leisure in Athens. Day 4: Thursday - Olympia CORINTH Canal (short stop). Drive to EPIDAURUS (visit the archaeological site and the theatre famous for its remarkable acoustics) and then on to NAUPLIA (short stop). Drive to MYCENAE where you visit the archaeological site, then depart for OLYMPIA, through the central Peloponnese area passing the cities of MEGALOPOLIS and TRIPOLIS arrive in OLYMPIA. Dinner & Overnight. Day 5: Friday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of OLYMPIA. Drive via PATRAS to RION, cross the channel to ANTIRION on the "state of the art" new suspended bridge considered to be the longest and most modern in Europe. Arrive in NAFPAKTOS, then continue to DELPHI.. Dinner & Overnight. Day 6: Saturday – Delphi In the morning visit the archaeological site and the museum of Delphi. Rest of the day at leisure. Dinner & Overnight in DELPHI. Day 6: Sunday – Kalambaka In the morning, start the drive by the central Greece towns of AMPHISSA, LAMIA and TRIKALA to KALAMBAKA. Afternoon visit of the breathtaking METEORA. Dinner & Overnight in KALAMBAKA. Day 7: Monday - Thessaloniki Drive by TRIKALA and LARISSA to the famous, sacred Macedonian town of DION (visit).Then continue to THESSALONIKI, the largest town in Northern Greece. -

(Selido ΤΟϜϟϣ 4

Δελτίο της Ελληνικής Γεωλογικής Εταιρίας, 2010 Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, 2010 Πρακτικά 12ου Διεθνούς Συνεδρίου Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Πάτρα, Μάιος 2010 Patras, May, 2010 GROUNDWATER QUALITY OF THE AG. PARASKEVI/TEMPI VALLEY KARSTIC SPRINGS - APPLICATION OF A TRACING TEST FOR RESEARCH OF THE MICROBIAL POLLUTIO (KATO OLYMPOS/NE THESSALY) Stamatis G. Agricultural University of Athens, Institute of Mineralogy-Geology, Iera Odos 75, GR-118 55 Athens, [email protected] . Abstract The study of the Kato Olympos karst system, based on the implementation of tracer tests and hydro- chemical analyses, is aimed at the investigation of surface-groundwater interaction, the delineation of the catchment area and the detection of the surface microbial source contamination of the Tempi karst springs. The study area is formed by intensively karstified carbonate rocks, metamorphic for- mations, Neogene sediments and Quaternary deposits. The significant karst aquifer discharges through karst springs in Tempi valley and in Pinios riverbed. The karst springs present important seasonal fluctuations in discharge rate, moderate mineralization with TDS between 562 to 630 mg/l + + - - and they belong to Ca-HCO3 water type. The inorganic pollution indicators, such as Na , K , Cl , NO3 + 3 , NH4 , PO4 , show low concentrations and do not reveal any surface influences. On the other hand, the presence of microbial parameters in karst springs proclaims the high rate of microbial contami- nation of karst aquifer. Tracer tests reveal hydraulic connection between the surface waters of Xirorema – Rapsani basin and the karst aquifer. The high values of groundwater flow velocity upwards of 200 m/h, show the good karstification rate of the carbonate formations and the cavy structure dom- inated in the study area, as well as the low self purification capability of the karst aquifer. -

Monuments.Pdf

© 2017 INTERPARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY ON ORTHODOXY ISBN 978-960-560 -139 -3 Front cover page photo Sacred Monastery of Mount Sinai, Egypt Back cover page photo Saint Sophia’s Cathedral, Kiev, Ukrania Cover design Aristotelis Patrikarakos Book artwork Panagiotis Zevgolis, Graphic Designer, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Editing George Parissis, HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | International Affairs Directorate Maria Bakali, I.A.O. Secretariat Lily Vardanyan, I.A.O. Secretariat Printing - Bookbinding HELLENIC PARLIAMENT | Publications & Printing Directorate Οι πληροφορίες των κειμένων παρέχονται από τους ίδιους τους διαγωνιζόμενους και όχι από άλλες πηγές The information of texts is provided by contestants themselves and not from other sources ΠΡΟΛΟΓΟΣ Η προστασία της παγκόσμιας πολιτιστικής κληρονομιάς, υποδηλώνει την υψηλή ευθύνη της κάθε κρατικής οντότητας προς τον πολιτισμό αλλά και ενδυναμώνει τα χαρακτηριστικά της έννοιας “πολίτης του κόσμου” σε κάθε σύγχρονο άνθρωπο. Η προστασία των θρησκευτικών μνημείων, υποδηλώνει επί πλέον σεβασμό στον Θεό, μετοχή στον ανθρώ - πινο πόνο και ενθάρρυνση της ανθρώπινης χαράς και ελπίδας. Μέσα σε κάθε θρησκευτικό μνημείο, περι - τοιχίζεται η ανθρώπινη οδύνη αιώνων, ο φόβος, η προσευχή και η παράκληση των πονεμένων και αδικημένων της ιστορίας του κόσμου αλλά και ο ύμνος, η ευχαριστία και η δοξολογία προς τον Δημιουργό. Σεβασμός προς το θρησκευτικό μνημείο, υποδηλώνει σεβασμό προς τα συσσωρευμένα από αιώνες αν - θρώπινα συναισθήματα. Βασισμένη σε αυτές τις απλές σκέψεις προχώρησε η Διεθνής Γραμματεία της Διακοινοβουλευτικής Συνέ - λευσης Ορθοδοξίας (Δ.Σ.Ο.) μετά από απόφαση της Γενικής της Συνέλευσης στην προκήρυξη του δεύτερου φωτογραφικού διαγωνισμού, με θέμα: « Καταστροφή των μνημείων της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής ». Επι πλέον, η βούληση της Δ.Σ.Ο., εστιάζεται στην πρόθεσή της να παρουσιάσει στο παγκόσμιο κοινό, τον πολιτισμικό αυτό θησαυρό της Χριστιανικής Ανατολής και να επισημάνει την ανάγκη μεγαλύτερης και ου - σιαστικότερης προστασίας του. -

DESERTMED a Project About the Deserted Islands of the Mediterranean

DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean The islands, and all the more so the deserted island, is an extremely poor or weak notion from the point of view of geography. This is to it’s credit. The range of islands has no objective unity, and deserted islands have even less. The deserted island may indeed have extremely poor soil. Deserted, the is- land may be a desert, but not necessarily. The real desert is uninhabited only insofar as it presents no conditions that by rights would make life possible, weather vegetable, animal, or human. On the contrary, the lack of inhabitants on the deserted island is a pure fact due to the circumstance, in other words, the island’s surroundings. The island is what the sea surrounds. What is de- serted is the ocean around it. It is by virtue of circumstance, for other reasons that the principle on which the island depends, that the ships pass in the distance and never come ashore.“ (from: Gilles Deleuze, Desert Island and Other Texts, Semiotext(e),Los Angeles, 2004) DESERTMED A project about the deserted islands of the Mediterranean Desertmed is an ongoing interdisciplina- land use, according to which the islands ry research project. The “blind spots” on can be divided into various groups or the European map serve as its subject typologies —although the distinctions are matter: approximately 300 uninhabited is- fluid. lands in the Mediterranean Sea. A group of artists, architects, writers and theoreti- cians traveled to forty of these often hard to reach islands in search of clues, impar- tially cataloguing information that can be interpreted in multiple ways. -

The Annual of the British School at Athens Meteora

The Annual of the British School at Athens http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH Additional services for The Annual of the British School at Athens: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Meteora A. H. Cruickshank The Annual of the British School at Athens / Volume 2 / November 1896, pp 105 - 112 DOI: 10.1017/S0068245400007103, Published online: 18 October 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068245400007103 How to cite this article: A. H. Cruickshank (1896). Meteora. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 2, pp 105-112 doi:10.1017/S0068245400007103 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH, IP address: 128.122.253.228 on 17 Apr 2015 METEOR A. METEORA. BY THE REV. A. H. CRUICKSHANK. PLATES II. AND III. A VISIT to the monasteries of Meteora is easier now than in 1834, when Curzon, escorted by a party of " klephts," reached them from the North. One feels, in reading the account of his rapid passage from Corfu to the valley of the upper Peneus and back again, that it was touch and go in those days. Now the traveller can approach Meteora by the railway, the chief outward and visible sign of improvement in the region assigned to Hellas by the Treaty of Berlin. To any one who has the time to spare I can strongly recommend a week in Thessaly, as it contains several objects of first-rate interest, and is in many respects unlike the rest of Greece. The population is largely Wallachian, and their bronzed shaggy faces suggest the uncomfortable thought, that the veneer of civilisation is even thinner than elsewhere in these parts. -

TANZIMAT in the PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) and LOCAL COUNCILS in the OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840S to 1860S)

TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde einer Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel von ANNA VAKALIS aus Thessaloniki, Griechenland Basel, 2019 Buchbinderei Bommer GmbH, Basel Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel, auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Maurus Reinkowski und Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yonca Köksal (Koç University, Istanbul). Basel, den 05/05/2017 Der Dekan Prof. Dr. Thomas Grob 2 ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………..…….…….….7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………...………..………8-9 NOTES ON PLACES……………………………………………………….……..….10 INTRODUCTION -Rethinking the Tanzimat........................................................................................................11-19 -Ottoman Province(s) in the Balkans………………………………..…….………...19-25 -Agency in Ottoman Society................…..............................................................................25-35 CHAPTER 1: THE STATE SETTING THE STAGE: Local Councils -

Grand Tour of Greece, 7 Days

GRAND TOUR OF GREECE Escorted Motor-Coach Tour Departure dates: April 22, May 13 & 27, June 24 & 26, July 15, August 5, September 9, 16 & 23 7 days / 6 nights: 1 night in Olympia, 1 night in Delphi, 1 night in Kalambaka, 3 nights in Thessaloniki Accommodation Meals Tours Transportation Transfer Also includes Olympia Breakfast daily Tours as per itinerary. Modern Airport transfers Professional tour Hotel Arty Grand or similar air-conditioned included if arrival and director (English Delphi For the Monasteries, motorcoach or departure is on the language only) Hotel Amalia or similar ladies are requested minibus. scheduled days. Kalambaka Hotel Amalia or similar to wear a skirt and Service charge & hotel Thessaloniki gentlemen long taxes Mediterranian Palace or similar trousers. Land Rates 2021 US$ per Person Day by Day Itinerary Dates Twin Single Day 1: 8:45am - departure from Athens. Drive on and visit the Theatre of Epidaurus. Then All dates $1,572 $1,998 proceed to the Town of Nafplio, drive on to Mycenae and visit their major sights. Then depart for Olympia the cradle of the ancient Olympic Games. Overnight here. ← Thessaloniki Day 2: In the morning visit the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus, the Ancient Stadium, the spot where the torch of the modern Olympic Games is lit and the Archaeological Museum. Then drive on through the plains of Ilia and Achaia. Pass by the picturesque towns of Nafpactos (Lepanto) and Itea, arrive in Delphi. ← Day 3: In the morning visit the Museum of Delphi, the most famous oracle of the ancient Kalabaka ← world. Depart for Kalambaka, a small town located at the foot of the astonishing complex of Meteora. -

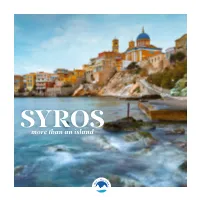

More Than an Island 2 MORE THAN an ISLAND

SYROS more than an island 2 MORE THAN AN ISLAND... ΧΧΧ TABLE OF CONTENTS Discovering Syros .................................... 4 Introduction From myth to history ............................. 6 History The two Doctrines .................................. 8 Religion will never forget the dreamy snowy white color, which got in my eyes when I landed in Syros at Two equal tribes this fertile land I dawn. Steamers always arrive at dawn, at this divide, where two fair cities rise all-white swan of the Aegean Sea that is as if it is with equal pride ...................................... 10 sleeping on the foams, with which the rainmaker is sprinkling. Kaikias, the northeast wind; on her Cities and countryside eastern bare side, the renowned Vaporia, which is Economy of Syros .................................... 14 always anchored beyond St. Nicholas, a fine piece of a crossway, and immortal Nisaki downtown, the Tourism, agricultural production, swan’s proud neck, with Vafiadakis’s buildings, and crafts and traditional shipbuilding the solid towers of the Customs Office, where the waves alive, as if they are hopping, laughing, run- Authentic beauty ..................................... 16 ning, chuckling, hunting, fighting, kissing, being Beaches, flora and fauna, habitats, baptized, swimming, brides white like foam. climate and geotourism At such time and in this weather, I landed on my dream island. I don’t know why some mysteries lie Culture, twelve months a year .......... 18 in man’s heart, always remaining dark and unex- Architecture, tradition, theatre, literature, plained. I loved Syra, ever since I first saw it. I loved music, visual arts and gastronomy her and wanted to see her again. I wanted to gaze at her once more. -

February Njv Athens Plaza News

P L A Z A N E W S A BUCKET LIST FEBRUARY 2020 FOR YOUR STAY IN ATHENS Q U E A R L O I M T Y D T N I A M E S P I I N T A L T E H V E A N R T S T H E N J V E X P E R I E N C E P L A Z A N E W S 0 1 Relax, enjoy, recharge at The NJV Athens Plaza before & after you head to the city French inspiration G r e e k - F r e n c h C h e f H e n r i G u i b e r t c r e a t e s 2 n e w s p e c i a l m e n u s c o m b i n i n g f a v o r i t e p r o d u c t s o f t h e G r e e k l a n d , f o l l o w i n g a F r e n c h t e c h n i q u e f o r t w o d i f f e r e n t m e n u s t h a t w i l l e n r i c h t h e A t h e n i a n g a s t r o n o m i c e x p e r i e n c e . -

Studies in Classical Antiquity NS Vol. 20 / 2011 New Zealand / South Africa

ISSN 1018-9017 SCHOLIA Studies in Classical Antiquity NS Vol. 20 / 2011 New Zealand / South Africa ISSN 1018-9017 SCHOLIA Studies in Classical Antiquity Editor: W. J. Dominik NS Vol. 20 / 2011 New Zealand / South Africa SCHOLIA Studies in Classical Antiquity ISSN 1018-9017 Scholia features critical and pedagogical articles and reviews on a diverse range of subjects dealing with classical antiquity, including late antique, medieval, Renaissance and early modern studies related to the classical tradition; in addition, there are articles on classical artefacts in museums in New Zealand and the J. A. Barsby Essay. Manuscripts: Potential contributors should read the ‘Notes for Contributors’ located at the back of this volume and follow the suggested guidelines for the submission of manuscripts. Articles on the classical tradition are particularly welcome. Submissions are usually reviewed by two referees. Time before publication decision: 2-3 months. Subscriptions (2011): Individuals: USD35/NZD50. Libraries and institutions: USD60/ NZD80. Credit card payments are preferred; please see the subscription form and credit card authorisation at the back of this volume. Foreign subscriptions cover air mail postage. After initial payment, a subscription to the journal will be entered. All back numbers are available at a reduced price and may be ordered from the Business Manager. Editing and Managing Address: Articles and subscriptions: W. J. Dominik, Editor and Manager, Scholia, Department of Classics, University of Otago, P. O. Box 56, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand. Telephone: +64 (0)3 479 8710; facsimile: +64 (0)3 479 9029; e-mail: [email protected]. Reviews Address: Reviews articles and reviews: J. -

The Prespa Agreement One Year After Ratification: from Enthusiasm to Uncertainty?

The Prespa Agreement one year after ratification: from enthusiasm to uncertainty? Ioannis ARMAKOLAS Ljupcho PETKOVSKI Alexandra VOUDOURI The Prespa Agreement one year after ratification: from enthusiasm to uncertainty? 1 The Prespa Agreement one year after ratification: from enthusiasm to uncertainty? This report was produced as part of the project “Harmonization of Bilateral Relations between North Macedonia and Greece through Monitoring the Implementation of the Prespa Agreement”, funded by the Canadian Fund for Local Initiatives, supported by the Canadian Embassy in Belgrade and implemented by EUROTHINK. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the donor. 2 The Prespa Agreement one year after ratification: from enthusiasm to uncertainty? The Prespa Agreement one year after ratification: from enthusiasm to uncertainty? Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 North Macedonia – from Enthusiasm to Realpolitik 5 2.1 The Nascent Golden age: Time of Enthusiasm 5 2.2 It’s Is not About Personalities, It’s is about National Interests:Political realism 6 2.3 Mismanaging Expectations, Well Managing Political Damage – the Period of Disappointment 8 3 The implementation of the Prespa Agreement under New Democracy government in Greece: Progress, Challenges, Prospects 10 3.1 Fierce Opposition: New Democracy in opposition and the Prespa Agreement 10 3.2 Initial Reluctance: New Democracy in office and the ‘hot potato’ of the Prespa Agreement 11 3.3 Turning Point: Greece’s diplomatic reactivation 12 3.4 Foreign Policy Blues: Difficult re-adjustment and Greek policy dilemmas 13 3.5 Bumpy Road Ahead? Uncertain prospects at home and abroad 15 4 Conclusions and key takeaways 18 5 Appendix – List of Official Documents Signed 20 6 Endnotes 21 7 Biography of the Authors 24 The Prespa Agreement one year after ratification: from enthusiasm to uncertainty? 3 1 Introduction n February 2019, the name Macedonia was replaced from boards in border crossings, in the Government web- I site and the signs in various governmental buildings.