Strategy for SME's International Expansion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differences in Energy and Nutritional Content of Menu Items Served By

RESEARCH ARTICLE Differences in energy and nutritional content of menu items served by popular UK chain restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross-sectional study ☯ ☯ Dolly R. Z. TheisID *, Jean AdamsID Centre for Diet and Activity Research, MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United a1111111111 Kingdom a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Background OPEN ACCESS Poor diet is a leading driver of obesity and morbidity. One possible contributor is increased Citation: Theis DRZ, Adams J (2019) Differences consumption of foods from out of home establishments, which tend to be high in energy den- in energy and nutritional content of menu items sity and portion size. A number of out of home establishments voluntarily provide consumers served by popular UK chain restaurants with with nutritional information through menu labelling. The aim of this study was to determine versus without voluntary menu labelling: A cross- whether there are differences in the energy and nutritional content of menu items served by sectional study. PLoS ONE 14(10): e0222773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222773 popular UK restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling. Editor: Zhifeng Gao, University of Florida, UNITED STATES Methods and findings Received: February 8, 2019 We identified the 100 most popular UK restaurant chains by sales and searched their web- sites for energy and nutritional information on items served in March-April 2018. We estab- Accepted: September 6, 2019 lished whether or not restaurants provided voluntary menu labelling by telephoning head Published: October 16, 2019 offices, visiting outlets and sourcing up-to-date copies of menus. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Licensing Sub-Committee, 29/03

Public Document Pack LICENSING SUB-COMMITTEE MEETING TO BE HELD IN CIVIC HALL, LEEDS ON TUESDAY, 29TH MARCH, 2016 AT 10.00 AM MEMBERSHIP Councillors A Khan Burmantofts and Richmond Hill; C Townsley Horsforth; G Wilkinson Wetherby; Agenda compiled by: Governance Services Civic Hall LEEDS LS1 1UR Tel No: 2243836 Produced on Recycled Paper A A G E N D A Item Ward Item Not Page No Open No PRELIMINARY PROCEDURES 1 ELECTION OF THE CHAIR 2 APPEALS AGAINST REFUSAL OF INSPECTION OF DOCUMENTS To consider any appeals in accordance with Procedure Rule 15.2 of the Access to Information Procedure Rules (in the event of an Appeal the press and public will be excluded) (*In accordance with Procedure Rule 15.2, written notice of an appeal must be received by the Head of Governance Services at least 24 hours before the meeting) B Item Ward Item Not Page No Open No 3 EXEMPT INFORMATION - POSSIBLE EXCLUSION OF THE PRESS AND PUBLIC 1) To highlight reports or appendices which: a) officers have identified as containing exempt information, and where officers consider that the public interest in maintaining the exemption outweighs the public interest in disclosing the information, for the reasons outlined in the report. b) To consider whether or not to accept the officers recommendation in respect of the above information. c) If so, to formally pass the following resolution:- RESOLVED – That the press and public be excluded from the meeting during consideration of those parts of the agenda designated as containing exempt information on the grounds that it is likely, in view of the nature of the business to be transacted or the nature of the proceedings, that if members of the press and public were present there would be disclosure to them of exempt information 2) To note that under the Licensing Procedure rules, the press and the public will be excluded from that part of the hearing where Members will deliberate on each application as it is in the public interest to allow the Members to have a full and frank debate on the matter before them. -

Nycfoodinspectionsimpleinbro

NYCFoodInspectionSimpleInBrooklynWO Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results DBA BORO STREET RAKUZEN Brooklyn FORT HAMILTON PARKWAY CAMP Brooklyn SMITH STREET LA ESTRELLA DEL CASTILLO Brooklyn NOSTRAND AVENUE RESTAURANT BROOKLYN CRAB Brooklyn REED STREET TIGER SUGAR Brooklyn 86 STREET MAZZAT Brooklyn COLUMBIA STREET DUNKIN Brooklyn JAY STREET YUMI BAKERY Brooklyn 20 AVENUE RENEGADES OF SUNSET Brooklyn 36 STREET HAPPY GARDEN Brooklyn GRAHAM AVENUE YANKY'S PIZZA Brooklyn 16 AVENUE KESTANE KEBAB Brooklyn NASSAU AVENUE ALI'S ROTI SHOP Brooklyn UTICA AVENUE MAMAN Brooklyn KENT STREET AL KOURA RESTAURANT Brooklyn 74 STREET NAIDRE'S CAFE Brooklyn 7 AVENUE CAFE MAX Brooklyn BRIGHTON BEACH AVENUE GREEN LAKE Brooklyn FLATBUSH AVENUE FURMAN'S COFFEE Brooklyn NOSTRAND AVENUE Page 1 of 759 09/30/2021 NYCFoodInspectionSimpleInBrooklynWO Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results ZIPCODE CUISINE DESCRIPTION 11219 Japanese 11201 American 11225 Latin American 11231 Seafood 11214 Coffee/Tea 11231 Middle Eastern 11201 Donuts 11204 Chinese 11232 Vegetarian 11206 Chinese 11204 Jewish/Kosher 11222 Turkish 11213 Caribbean 11222 French 11209 Middle Eastern 11215 Coffee/Tea 11235 American 11226 Chinese 11216 Coffee/Tea Page 2 of 759 09/30/2021 NYCFoodInspectionSimpleInBrooklynWO Based on DOHMH New York City Restaurant Inspection Results INSPECTION DATE 08/26/2019 11/06/2019 09/24/2019 04/20/2019 08/11/2021 08/17/2021 12/17/2018 01/14/2019 10/02/2019 03/11/2019 08/30/2018 12/18/2018 06/06/2019 12/05/2018 03/19/2018 07/22/2021 08/25/2021 -

Trade Mark Invalidity Decision O/144/03

TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF REGISTRATION NO. 2111700 IN THE NAME OF DIXY FRIED CHICKEN (EURO) LTD AND IN THE MATTER OF AN APPLICATION FOR A DECLARATION OF INVALIDITY UNDER NO. 12056 IN THE NAME OF DIXY FRIED CHICKEN (STRATFORD) LTD TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF registration No. 2111700 in the name of Dixy Fried Chicken (Euro) Ltd And IN THE MATTER OF an Application for a Declaration of Invalidity under No. 12056 in the name of Dixy Fried Chicken (Stratford) Ltd Background 1. Trade mark registration 2111700 stands on the Trade Marks register in the name of Dixy Fried Chicken (Euro) Ltd, and in respect of a specification of goods as follows: Chicken and chicken products; all included in Class 29. 2. The mark is as follows: 3. On 8 November 2000, Dixy Fried Chicken (Stratford) Ltd made an application under Section 47(1) and 47(2) of the Act to have the trade mark registration declared invalid. The grounds of the application are, in summary: 1. Under Section 3(1)(a) because the mark is devoid of distinctive character and is not capable of distinguishing the proprietor’s goods, 2. Under Section 3(1)(d) because the word DIXY is common to the trade for Fried Chicken restaurant and take-away’s, and is a generic term for the product, 3. Under Section 3(6) because the application was made in the full knowledge that the mark was being used by many traders. 4. Under Section 5(4)(a) because of the applicant’s earlier rights. -

A Handy Little Guide to Stoke-On-Trent City Centre So Here You Are

A handy little guide to Stoke-on-Trent City Centre So here you are. Stokie Glossary .........................................................4 A new city, an abundance of A #COVIDConfident Place To Be ...............5 City Centre map .................................................6-7 potential at your feet, new The Cultural Quarter ......................................8-9 friends to be made, nights out The Hive ...............................................................10 - 11 Hotels .............................................................................12 to be enjoyed and of course a Make a dorm your home ...............................13 degree to be achieved… Live music venues .......................................14-15 Sweet tooth ..............................................................16 Welcome to Stoke-on-Trent Gear up for the year ahead .........................17 City Centre! Different things to do ...............................18-19 Our Front Door ......................................................19 It’s been a funny few months with all this Bit of a foodie? You’ll find dozens of Coffee fix ....................................................................20 pandemic business, hasn’t it? You’ll be restaurants, from small indie bars and pleased to know that all of our retail and cafés, to your favourite chains, with Quick eats ..................................................................21 hospitality venues have implemented all cuisines spanning all corners of the globe, Big night out ....................................................22-23 -

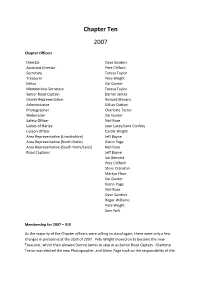

Chapter Ten 2007

Chapter Ten 2007 Chapter Officers Director Dave Sanders Assistant Director Pete Clifford Secretary Teresa Taylor Treasurer Pete Wright Editor Dai Gunter Membership Secretary Teresa Taylor Senior Road Captain Darren James Dealer Representative Richard Stevens Administrator Gillian Dutton Photographer Charlotte Tector Webmaster Dai Gunter Safety Officer Neil Rose Ladies of Harley Jean Lacey/Jane Confrey Liaison Officer Carole Wright Area Representative (Lincolnshire) Jeff Bayne Area Representative (North Notts) Glenn Page Area Representative (South Notts/Leics) Neil Rose Road Captains Jeff Bayne Ian Bennett Pete Clifford Steve Cranston Martyn Flear Dai Gunter Glenn Page Neil Rose Dave Sanders Roger Williams Pete Wright Sam York Membership for 2007 – 310 As the majority of the Chapter officers were willing to stand again, there were only a few changes in personnel at the start of 2007. Pete Wright moved on to become the new Treasurer, which then allowed Darren James to step in as Senior Road Captain. Charlotte Tector was elected the new Photographer, and Glenn Page took on the responsibility of the North Nottinghamshire area representative. Later in the year, Sue Thomas took over as Secretary, leaving Teresa Taylor to concentrate on Membership Secretary. The addition of three new Road Captains brought the number up to a healthy thirteen in total. As the North Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire area representatives had organised their separate Christmas functions at the end of last year, the Chapter function was held over to the start of this year, taking the form of a Medieval Banquet in Nottingham. The events programme then took on a familiar look, with regular Sunday ride-outs and four Saturday Ladies of Harley Cream Tea rides between May and August. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Licensing Sub-Committee, 29/09

Public Document Pack LICENSING SUB-COMMITTEE MEETING TO BE HELD IN CIVIC HALL, LEEDS ON TUESDAY, 29TH SEPTEMBER, 2015 AT 10.00 AM MEMBERSHIP Councillors M Harland Kippax and Methley; A Khan Burmantofts and Richmond Hill; G Wilkinson Wetherby; Agenda compiled by: Governance Services Civic Hall LEEDS LS1 1UR Tel No: 2243836 Produced on Recycled Paper A A G E N D A Item Ward Item Not Page No Open No PRELIMINARY PROCEDURES 1 ELECTION OF THE CHAIR 2 APPEALS AGAINST REFUSAL OF INSPECTION OF DOCUMENTS To consider any appeals in accordance with Procedure Rule 15.2 of the Access to Information Procedure Rules (in the event of an Appeal the press and public will be excluded) (*In accordance with Procedure Rule 15.2, written notice of an appeal must be received by the Head of Governance Services at least 24 hours before the meeting) B Item Ward Item Not Page No Open No 3 EXEMPT INFORMATION - POSSIBLE EXCLUSION OF THE PRESS AND PUBLIC 1) To highlight reports or appendices which: a) officers have identified as containing exempt information, and where officers consider that the public interest in maintaining the exemption outweighs the public interest in disclosing the information, for the reasons outlined in the report. b) To consider whether or not to accept the officers recommendation in respect of the above information. c) If so, to formally pass the following resolution:- RESOLVED – That the press and public be excluded from the meeting during consideration of those parts of the agenda designated as containing exempt information on the grounds that it is likely, in view of the nature of the business to be transacted or the nature of the proceedings, that if members of the press and public were present there would be disclosure to them of exempt information 2) To note that under the Licensing Procedure rules, the press and the public will be excluded from that part of the hearing where Members will deliberate on each application as it is in the public interest to allow the Members to have a full and frank debate on the matter before them. -

Winning Restaurant Chains in Europe

. foodservicevision.fr 74 bld du 11 novembre 1918 F-69100 Villeurbanne A simplified joint-stock company (SAS) with a share capital of EUR 53,550 T. +33(0)437 450 265 - F. +33(0)437 454 974 483896338 RCS Lyon In a rapidly changing food service market, the chain market is growing in Europe, but with great disparities between historical brands and new concepts: Many historical market chains are suffering... "How can I regain consumer appeal?" "What are my options to improve my concept with regard to consumer expectations?" "How can I regain attractiveness among operators and key property players?" Recent concepts are particularly dynamic... "How can I succeed not only in creating, but also in deploying an attractive concept?" At the same time, at a time when shopping centers have never been so numerous, operators, franchisors and key property players are increasingly looking for attractive and differentiating "city center" concepts... "How can I identify the most promising concepts to attract customers to my area?" "What are the winning models and key success factors?" "What are the key expectations of winning chains in terms of differentiation and preference?" Finally, the catering sector is of great interest to specialized funds.... "How can I identify promising concepts for the future or make concepts evolve to make them more attractive?" "What are the specificities in each country?" "What are the most attractive chains? And the least attractive ones?" What are the winning recipes for concepts today in Europe? foodservicevision.fr 74 bld du 11 novembre 1918 F-69100 Villeurbanne A simplified joint-stock company (SAS) with a share capital of EUR 53,550 T. -

Prime Freehold Drive Thru Investment

A483 Prime Freehold Drive Thru Investment Oswestry Gateway Mile End Roundabout Maes-y-Clawdd Estate Road SY10 8NN Oswalds Cross PH B4579 Shrewsbury Road Oswestry INVESTMENT Location Oswestry is an attractive and historic market town situated close to the Welsh border in the north west of Shropshire. It acts SUMMARY as a commercial centre for a large agricultural hinterland and is approximately 21 miles north west of Shrewsbury and 16 miles south of Wrexham. _ Prime roadside location at the very busy junction of The town benefits from good road links via the A5 connecting Oswestry to Shrewsbury, the M54 and the M6 motorways. A5 and A483 at Mile End Roundabout with an average vehicle count per day of 26,682 vehicles The town has a district population of approximately 37,000 rising to over 130,000 within 12.5 miles of the town centre. in 2017 (counted approximately 1 mile north of the property). _ Units trade as Starbucks, KFC and OK Diner. _ Freehold. _ Property is let on leases which expire in 2031 and 2033 with breaks in 2028 with a minimum increase in 2021 and the next open market rent reviews in 2023. _ The rents on the units trading as KFC and Starbucks have recently been settled at third party with a 2018 rent review reflecting £37.50 per sq ft on Starbucks and £29 per sq ft on KFC. _ The current income therefore is £166,200 per annum exclusive of VAT with an inbuilt reversion in the OK Diner lease and a projected minimum income at next review in 2021 of £168,800 per annum. -

Review of Licensing Policy Report

ENCLOSURE 9.1 CANNOCK CHASE COUNCIL COUNCIL 8 DECEMBER 2010 REPORT OF DIRECTOR OF SERVICE IMPROVEMENT RESPONSIBLE PORTFOLIO LEADER: ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF LICENSING POLICY KEY DECISION – YES 1. Purpose of Report 1.1 To seek approval and adoption of Cannock Chase District Council’s revised Licensing Policy in respect of functions under the Licensing Act 2003, following consultation on statutory review. 2. Recommendations 2.1 That the Cannock Chase District Council approves and adopts the revised Licensing Policy given at Annex 3 of this report. 3. Summary (inc. brief overview of relevant background history) 3.1 The Licensing Act 2003 received Royal Assent in July 2003 and modernises the old licensing regimes. It integrates alcohol, public entertainment, cinema, theatre, late night refreshment and night café licensing with a single system which places a statutory duty on the Council, as the Licensing Authority, to promote the four licensing objectives:- • the prevention of crime and disorder • public safety • the prevention of public nuisance • the protection of children from harm 3.2 The Licensing Policy is the instrument by which the Council administers enforces and executes its duties under the Act. It became operational on 7 February, 2005 and was approved and adopted by the Council on 13 December, 2004, and amended by Council on 23 February, 2005 to include the Weights and Measures Authority (Trading Standards) as a Responsible Authority following an amendment to the legislation. 3.3 It was reviewed during 2007 and the revised Licensing Policy approved and adopted by Council on 5 December 2007. Report-Review of Licensing Policy ENCLOSURE 9.2 4. -

Table of Stakeholder Engagement March 2019 to July 2019

Reduction and reformulation programme Table of stakeholder engagement March 2019 to July 2019 Stakeholder engagement March 2019 to July 2019 PHE publications gateway number: GW-663 The table below shows stakeholder engagement with the reduction and reformulation programmes covered by Public Health England (PHE) between March 2019 and July 2019. This engagement covers, for example, business 1:1 discussions on sugar and calorie reduction and meetings with the eating out of home sector businesses that had not yet engaged with the reduction and reformulation programmes. It is our understanding that many businesses are working towards achieving the aims and ambitions of the programmes but would not have necessarily had direct engagement with PHE during this timeframe. The programmes are at different stages and this is reflected in the level and focus of engagement with businesses and other stakeholders in the table below. Although every effort has been taken for this table to be comprehensive there may be some instances where this has not been possible. Table of stakeholder engagement March 2019 to July 2019 Sugar Out of home Calorie Baby food reduction business reduction reformulation engagementi,ii Retailers Asda Stores ✓ ✓ ✓ Limited Lidl UK ✓ ✓ Manufacturers General Mills ✓ ✓ Haribo ✓ ✓ Mondelez ✓ ✓ Premier Foods ✓ ✓ Unilever UK Limited ✓ ✓ Out of home businesses Bistrot Pierre ✓ Chopstix Group UK ✓ Comptoir Libanais ✓ Dixy Chicken ✓ Franco Manca ✓ Just Eat ✓ Pizza Hut ✓ Restaurants TGI Fridays UK ✓ Whitbread ✓ Trade Associations British -

Review of Licensing Policy

ENCLOSURE 9.1 CANNOCK CHASE COUNCIL COUNCIL 5 DECEMBER, 2007 DIRECTOR OF SERVICE IMPROVEMENT REVIEW OF LICENSING POLICY 1. Purpose of Report 1.1 To seek approval and adoption of Cannock Chase District Council’s revised Licensing Policy in respect of functions under the Licensing Act 2003, following consultation on statutory review. 2. Recommendations 2.1 That the Cannock Chase District Council approves and adopts the revised Licensing Policy given at Annex 3 of this report. 3. Key Issues 3.1 Section 5 of the Licensing Act 2003 requires the Council to prepare and consult on a statement of licensing policy and to review every 3 years the approved, adopted document to ensure its effectiveness in meeting the licensing objectives. 3.2 This report details the review process which has resulted in a revised Licensing Policy. S:\Corporate\Meetings-Council\2007-08\Council\07-12-05\06a-Report Review Of Licensing Policy.Doc ENCLOSURE 9.2 REPORT INDEX Background Section 1 The Policy Section 2 Consultation Response Section 3 Conclusion Section 4 Contribution to CHASE Section 5 Section 17 (Crime Prevention) Implications Section 6 Human Rights Act Implications Section 7 Data Protection Act Implications Section 8 Risk Management Implications Section 9 Legal Implications Section 10 Financial Implications Section 11 Human Resource Implications Section 12 List of Background Papers Section 13 Annexes to the Report i.e. Copies of Correspondence, Plans etc. Annex 1: Annex 1 Annex 2: Annex 2 Annex 3: Annex 3 S:\Corporate\Meetings-Council\2007-08\Council\07-12-05\06a-Report Review Of Licensing Policy.Doc ENCLOSURE 9.3 Section 1 1.