Mirroring the Other by Allison Hodgkins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

Fauda : Zoom Avant Sur Le Chaos ÉRIC CLÉMENS L’Europe Devant La Question Juive BRUNO KARSENTI L’État Juif Est Un État Fait Pour Les Juifs JACQUES SOJCHER Israël

Editorial, Richard Miller DOSSIER ISRAËL FRANÇOIS ENGLERT Hommage aux Justes : témoignage d’un enfant caché MICHEL GHEUDE Le sujet qui fâche RICHARD MILLER Du Bauhaus au sionisme ÉLIE BARNAVI L’après Rabin ère GUY HAARSCHER N° 1 1 année – Automne 2019 N° 1 « Pro Israël Pro Peace » Fondateurs : Richard Miller et Jean Meurice THE AGREEMENT DE DAVID BROGNON ET STÉPHANIE ROLLIN DOMINIQUE COSTERMANS PHILOSOPHIE . CULTURE . POLITIQUE . ART Fauda : zoom avant sur le chaos ÉRIC CLÉMENS L’Europe devant la question juive BRUNO KARSENTI L’État juif est un État fait pour les Juifs JACQUES SOJCHER Israël Sionisme, antisionisme et antisémitisme TESSA PARZENCZEWSKI À travers romans et nouvelles, que nous dit Amos Oz ? JACQUES BROTCHI Mon vœu le plus cher : une solution à deux Etats DOSSIER VARIA VINCENT DE COOREBYTER Aux origines de la laïcité Israël FRANÇOIS ENGLERT, MICHEL GHEUDE, RICHARD MILLER, ELIE BARNAVI, LUC RICHIR GUY HAARSCHER, DOMINIQUE COSTERMANS, ERIC CLÉMENS, BRUNO KARSENTI, JACQUES SOJCHER, TESSA PARZENCZEWSKI, JACQUES BROTCHI Le dernier homme DOSSIER LAMBROS COULOUBARITSIS VARIA : VINCENT DE COOREBYTER, LUC RICHIR, LAMBROS COULOUBARITSIS De la multi-culturalité à l’inter-culturalité européenne Ulenspiegel ACTUALITÉS DES EDITIONS DU CEP VÉRONIQUE BERGEN L’odyssée poético-politique de Jean-Louis Lippert FÉLIX HANNAERT peintures dessins/schildereien tekeningen/1980 2020 Cahier d’illustrations : Photographies et dessins en rapport avec des textes Les éditions du CEP Créations . Europe . Perspectives 14 € Créations . Europe . Perspectives Dominique Costermans Fauda : zoom avant sur le chaos Fauda arrive, Fauda revient. À l’origine conçue pour un public israélien, la série de Lior Raz et d’Avi Issacharoff a désormais conquis une audience internationale depuis sa diffusion par Netflix. -

Nimrod Barkan > P

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING OUR TU BI’SHEVAT CAMPAIGN VISIT ISRAEL WITH JNF: JNFOTTAWA.CA [email protected] 613.798.2411 Ottawa Jewish Bulletin FEBRUARY 20, 2017 | 24 SHEVAT 577 ESTABLISHED 1937 OTTAWAJEWISHBULLETIN.COM | $2 Hundreds gather to do good deeds on Mitzvah Day Mitzvah Day 2017 was marked by the performance of good deeds by young and old – and those in between – along with a celebration of Canada 150. Louise Rachlis reports. he Soloway Jewish Community Lianne Lang of CTV was MC for the Centre (SJCC) and Hillel Lodge event. She praised the “hard work and were buzzing with activity as dedication” of Mitzvah Day Chair Cindy ISSIE SCAROWSKY Eli Saikaley of Silver Scissors Salon supervises Mitzvah Day celebrity haircutters (from left) hundreds of volunteers – from Smith and her planning committee, and T Jeff Miller of GGFL, Mayor Jim Watson and City Councillor Jean Cloutier as they prepare to cut at preschoolers to seniors – gathered, acknowledged the Friends of Mitzvah least six inches of hair from Sarah Massad, Yasmin Vinograd and Liora Shapiro to be used by February 5, on the Jewish Community Day for their support, and GGFL Hair Donation Ottawa to make wigs for cancer patients experiencing medical hair loss. Campus and several off-site locations, to Chartered Professional Accountants, the participate in the Jewish Federation of Mitzvah Day major sponsor for the past Ottawa’s annual Mitzvah Day. eight years. In recognition of Canada’s sesquicen- Hair donations for Hair Donation tennial, a Canada 150 theme was incor- Ottawa – an organization that provides porated into many of the good deeds free wigs for cancer patients experiencing performed. -

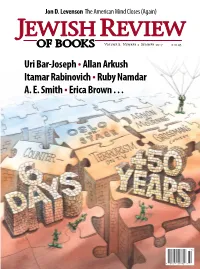

Uri Bar-Joseph •Allan Arkush Itamar Rabinovich •Ruby Namdar A. E

Jon D. Levenson The American Mind Closes (Again) JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 8, Number 2 Summer 2017 $10.45 Uri Bar-Joseph • Allan Arkush Itamar Rabinovich • Ruby Namdar A. E. Smith • Erica Brown . Editor Abraham Socher FASCINATING SERIES BY MAGGID BOOKS Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld MAGGID MODERN CLASSICS Managing Editor Introduces one of Israel’s most creative and influential thinkers Amy Newman Smith Editorial Assistant Kate Elinsky FAITH SHATTERED Editorial Board AND RESTORED Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Judaism in the Postmodern Age Rabbi Shagar Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Jon D. Levenson The starkly innovative spiritual and educational Anita Shapira Michael Walzer approach of Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier (known as Rabbi Shagar) has shaped a generation of Israelis who yearn to encounter the Divine in a world Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein progressively at odds with religious experience, nurturing religious faith within a cultural climate Publisher of corrosive skepticism. Here, Rabbi Shagar offers Eric Cohen profound and often acutely personal insights that marry existentialist philosophy and Hasidism, Advancement Officer Talmud and postmodernism. Malka Groden Published for Associate Publisher the 1st time The seminal essays in Faith Shattered and Restored in English! sets out a new path for preserving and cultivating Dalya Mayer Jewish spirituality in the 21st century and beyond. Chairman’s Council Anonymous Blavatnik Family Foundation Publication Committee Marilyn and Michael Fedak Ahuva and Martin J. Gross Susan and Roger Hertog MAGGID STUDIES IN TANAKH Roy J. Katzovicz Inaugurates new volume on Humash. The Lauder Foundation– Leonard and Judy Lauder Tina and Steven Price Charitable Foundation Pamela and George Rohr GENESIS Daniel Senor From Creation to Covenant Paul E. -

May 1, 2018 16 Iyar 5778

The Aaronion 616 S. Mississippi River Blvd, St. Paul, MN 55116- 1099 • (651) 698 -8874 • www.TempleofAaron.org Vol. 93 • No. 9 May 1, 2018 16 Iyar 5778 Minnesota’s Annual AIPAC Event May 3, 2018 AIPAC invites you to hear A Year of Veganism Mosab Hassann Yousef, In 2017, we were honored to receive a grant from the author of Son of Hamas , the Jewish organization Shamayim V’Aretz which is a former Hamas operative. devoted to ethical eating and treatment of animals. This grant contained a challenging question for the staff: How do we use food to engage the concepts of Kashrut and mirror them with a modern Jewish approach? From an Israeli vegan lunch to collaborating with local Kosher and vegan vendors, the grant enabled Rabbi Jeremy Fine Temple of Aaron to create a new way for us to think 651 -698 -8874 x112 about one of the pillars of Judaism. I want to thank Email: member Howard Goldman for helping recruit [email protected] Twitter: Christine Coughlin who spoke on ethical eating and @RabbiJeremyFine all of you who have come to these events with an open mind (and belly). Trying a “new” way of eating or a Jewish experience takes an incredible amount of openness. Whether it be a change in the synagogue or in the home, Jewish customs Mosab Hassan Yousef was born in need constant innovative approaches to allow all of us the access holidays and Ramallah, in Israel’s West Bank in rituals. 1978. His father, Sheikh Hassan Yousef, is a founding leader of Hamas, Shavuot is a break from our constant. -

Nov 5-21, 2017 Los Angeles

NOV 5-21, 2017 LOS ANGELES WWW.ISRAELFILMFESTIVAL.COM © 2017 A presentation of the IsraFest Foundation, Inc. Key art designed by eclipse. FILM GUIDE | SCREENING SCHEDULE | EVENTS MISSION AND HONORARY COMMITTEE NOTE FROM THE FESTIVAL’S FOUNDER & EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR HONORARY MEIR FENIGSTEIN COMMITTEE FOUNDER / DIRECTOR WELCOME TO THE 31ST ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL Meir Fenigstein CHAIRMAN Adam Berkowitz Dear Friends, HONORARY CHAIRMAN Arnon Milchan On behalf of the IsraFest Foundation, Inc. and its family of filmmakers and sponsors, I would like to welcome you to our 31ST ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL in Los Angeles. HONORARY COMMITTEE This is an exciting chapter in our Festival’s ongoing adventure, as we start our 4th Sheldon G. Adelson decade as the largest showcase of Israeli films in the United States, and one of its Beny Alagem oldest and most prestigious foreign film festivals. Gila Almagor This year we are pleased to introduce close to 40 new feature films, thought- Avi Arad provoking documentaries, innovative television series, and award-winning shorts. Arthur Cohen 25 Israeli filmmakers will attend the various screenings and events to meet the Beverly Cohen audience and introduce their work. We are proud to announce our first ever Robert DeNiro television-focused program: Israeli TV – An American Success Story as we celebrate the success of Israeli television in the American marketplace. Danny Dimbort Michael Douglas We extend our sincerest congratulations to this year’s Festival honorees Jeffrey Richard Dreyfuss Tambor, recipient of the 2017 IFF Achievement in Television Award, and Lior Meyer Gottlieb Ashkenazi, recipient of the 2017 Cinematic Achievement Award, for their amazing Peter Guber accomplishments, as well as their abiding friendship to Israel and Israeli culture. -

Orientalism – a Netflix Unlimited Series

930901-0313 Orientalism – A Netflix Unlimited Series A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of The Orientalist Representations of Arab Identity in Netflix Film and TV By: Stefan Maatouk Peace and Conflict Studies Bachelor’s Thesis Spring 2021 Supervisor: Ivan Gusic Stefan Maatouk 930901-0313 Abstract Orientalism was a term developed by post-colonial theorist Edward Said to describe the ways in which Europeans, or the West, portrayed the Orient as inferior, uncivilised, and wholly anti- Western. Netflix Inc., the world’s largest subscription based streaming service, which as of 2018, expanded its streaming venue to over 190 countries globally, is the wellspring of knowledge for many people. Through the multimodal critical discourse analysis of 6 Netflix films and television programmes (Stateless, Gods of Egypt, Messiah, Al Hayba, Sand Castle, and Fauda) the study examines the extent to which the streaming giant is culpable in the reproduction of Orientalist discourses of power, i.e., discourses which facilitate the construction of the stereotyped Other. The results have shown that Netflix strengthens, through the dissemination and distribution of symbols and messages to the general population, the domination and authority over society and its political, economic, cultural, and ideological domains. Using Norman Fairclough’s approach to critical discourse analysis combined with a social semiotic perspective, this study endeavours to design a comprehensive methodological and theoretical framework which can be utilized by future researchers to analyse and critique particular power dynamics within society by exposing the dominant ideological world-view distortions which reinforce oppressive structures and institutional practices. Keywords: Netflix, Orientalism, Othering, Critical Discourse Analysis, Media, Power, Knowledge, Ideology, Hegemony Word Count:13,979 ii Stefan Maatouk 930901-0313 “There is nothing mysterious or natural about authority. -

The Rise of the Israeli Drama in a Global Market

Kedma: Penn's Journal on Jewish Thought, Jewish Culture, and Israel Volume 2 Number 1 Spring 2018 Article 2 2020 The Rise of the Israeli Drama in a Global Market Danny Rubin University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma/vol2/iss1/2 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rise of the Israeli Drama in a Global Market Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Kedma: Penn's Journal on Jewish Thought, Jewish Culture, and Israel: https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma/vol2/iss1/2 photo by Heather Sharkey The Rise of the Israeli Drama in a Global Market Danny Rubin Introduction Even though there are only 9 million people in the world who can speak Hebrew, Israeli television dramas have made inroads in the global market. This interest started in 2005 when American premium cable network HBO purchased the option to adapt the Israeli show BeTipul. BeTipul is a riveting drama that follows psychologist Reuven Dagan through his weekly meetings with his patients. HBO’s adaptation, the critically acclaimed In Treatment, won a Primetime Emmy in 2008 and a Golden Globe in 2009.1 More recently, the streaming provider Netflix has “gone truly Israeli,” and Series II Issue Number 1 Spring 2018/5778 • 21 now features -

Pdf [Accessed: 31/05/2016]

VICTIMHOOD AS A DRIVING FORCE IN THE INTRACTABILITY OF THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: Reflections on Collective Memory, Conflict Ethos, and Collective Emotional Orientations A Thesis by Emad S. Moussa January 2020 A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors Prof. Barry Richards & Dr. Chindu Sreedharan Faculty of Media and Communications This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 1 IN MEMORY OF MY GRANDPARENTS Moussa and Aisha AND, TO MY GRANDMOTHER Ghefra Ghannam From whom I learned about a vanished homeland 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This work would not have been possible without the help and guidance of my supervisors, Prof. Barry Richards and Dr. Chindu Sreedharan. I have benefited immeasurably from their insight and rich academic experience. Nobody has been more important to me in the pursuit of this project than the members of my family. I would like to offer my profound appreciation to my loving wife, Amanda, for her support and extraordinary patience. Somewhat, I also feel obliged to thank my little one, Sanna, who despite her unquenchable curiosity and endless stream of questions, was grownup enough to understand that sometimes daddy needed some quiet time to work on his project. Of course, I would like to thank my parents, whose love and guidance are with me in whatever I pursue. -

He Made the Call to Cancel Summer Camp for 10,000 Kids. Here's What

YOUR SHABBAT EDITION • MAY 1, 2020 Stories for you to savor over Shabbat and through the weekend, in printable format. Sign up at forward.com/shabbat. News He made the call to cancel summer camp for 10,000 kids. Here’s what he has to say. By Aiden Pink Ruben Arquilevich is a Jewish summer camp guy. He Arquilevich talked to the Forward a few minutes after says his life was shaped by Jewish summer camp. Over the URJ announced that all 15 of its camps — serving the past three decades, he’s been a camper, a 10,000 campers — would be closed this summer counselor, a professional staffer and the director of a because they did not think they could operate safely Jewish summer camp. He met his wife at Jewish given the COVID-19 pandemic. He said he knew how summer camp. He sent his kids to Jewish summer sad this would be for thousands of Jewish children camp. Now he’s a vice president of the Union for who’ve been cooped up at home, dreaming of seeing Reform Judaism, in charge of North America’s largest their camp friends – because his family was going network of Jewish summer camps. through the same grieving process. We want to hear from you: The year of no “There was something so powerful my daughter said,” summer camp Arquilevich recounted. “She knows that we can’t have camp together in person this summer, and that we And for the past few days, he had been keeping a should not have camp. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „FAUDA und der Andere“ verfasst von / submitted by Verena Hanna angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2017/ Vienna, 2017 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 589 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Internationale Entwicklung degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Frank Stern L’impression d’altérité n’est qu’une illusion. – Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt Seite I DEUTSCHSPRACHIGES ABSTRACT Mit Said lassen sich Werke der Populärkultur auf eine gegebenenfalls orientalistische Darstellungsweise des „Anderen“ untersuchen. Gemeinsam mit Simmels Exkurs über den Fremden und Freuds Ausführungen zu dem „Unheimlichen“ wird dies daher anhand der systematischen Filmanalyse nach Korte herangezogen, um die israelische Serie FAUDA auf ihre Differenzierung zwischen israelischen „Eigenen“ und palästinensischen „Anderen“ zu untersuchen. Ergänzt durch eine Inhaltsanalyse arabisch- und hebräischsprachiger Rezensionen zeichnet sich das Bild ab, dass orientalistischen Zügen in der Serie entweder direkt durch die Handlung widersprochen oder diese aber durch stilistische Mittel künstlerisch subvertiert werden. Die Analyse über Simmel und Freud zeigt, dass das Andere zwar als solcher auch präsentiert wird, durch den Einsatz von Doppelungen jedoch Zusammenhänge zum Eigenen geschaffen werden und die Sinnhaftigkeit der Eskalation des Konflikts in Frage gestellt wird. ENGLISCHSPRACHIGES ABSTRACT Said’s theory on orientalism lends itself to analysing popular culture and its presentation of the “Other”. In combination with Simmel’s excursion on the stranger and Freud’s explanations on the “uncanny”, this is used to analyse the Israeli series FAUDA and its differentiation between the Israeli “Own” and Palestinian “Other”, utilizing Korte’s systematic film analysis. -

FAUDA Une Série Créée Et Écrite Par Lior Raz Et Avi Issacharoff Avec Lior Raz, Hisham Suliman, Shadi Mar’I, Laetitia Eido…

FAUDA Une série créée et écrite par Lior Raz et Avi Issacharoff Avec Lior Raz, Hisham Suliman, Shadi Mar’i, Laetitia Eido… Une unité d’élite israélienne opère sous couverture en Palestine et élimine "La Panthère", l’un des terroristes les plus dangereux de la planète. Quelques années plus tard, les services secrets reçoivent une information capitale : "La Panthère" est toujours en vie. Ex-infiltré, Doron Kabilio va reprendre du service pour débusquer son pire ennemi. Une lutte à mort entre l’unité antiterroriste israélienne et "La Panthère" va commencer… ENTRE AGENTS ET TERRORISTES, LA FRONTIÈRE N’EXISTE PLUS LA SÉRIE AU SUCCÉS MONDIAL Fauda ("chaos" en arabe) est la série d’action qui bat tous les records d’audience en Israël et en Palestine, une plongée inédite au cœur des deux camps. Mêlant habilement tension, drame, suspense et confusion, Fauda est une des meilleures séries du moment. À découvrir d’urgence ! - FIPA d’Or du Meilleur Scénario Original – L’intégrale de la Saison 1 en Coffret 3 DVD le 10 Janvier Matériel promotionnel disponible sur demande - Images et visuels via CARACTÉRISTIQUES TECHNIQUES DVD Format image : 1.77, 16/9 ème compatible 4/3 Format son : Français & Hébreu/Arabe Dolby Digital 2.0 Sous-titres: Français Durée : 12 épisodes de 40’ COMPLÉMENTS : - Making-of (23’) - Exclusivité : la bande-annonce de la Saison 2 Prix public indicatif : 29,99 € le Coffret 3 DVD - déjà disponible en téléchargement définitif – PRESSE WEB : agence CARTEL Youssef Lemhouer - [email protected] / Jean Baptiste-Péan - [email protected] WILD SIDE VIDEO - [ SERVICE DE PRESSE : Benjamin GAESSLER & Cassiopeia BASSIS ] Tél : 01.43.13.22.10 ou 22.32 / [email protected] + [email protected] – 65, Rue de Dunkerque 75009 PARIS Retrouvez-nous : www.wildside.fr - /WildSideOfficiel - @wildsidecats LES PERSONNAGES Doron Kabilio (Lior Raz) Personnage emblématique de la série, il est l’ancien chef de l’unité d’infiltration qui reprend du service à l’annonce de la réapparition de "La Panthère".