Momentum Analysis of Flow Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluid Mechanics

FLUID MECHANICS PROF. DR. METİN GÜNER COMPILER ANKARA UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURAL MACHINERY AND TECHNOLOGIES ENGINEERING 1 1. INTRODUCTION Mechanics is the oldest physical science that deals with both stationary and moving bodies under the influence of forces. Mechanics is divided into three groups: a) Mechanics of rigid bodies, b) Mechanics of deformable bodies, c) Fluid mechanics Fluid mechanics deals with the behavior of fluids at rest (fluid statics) or in motion (fluid dynamics), and the interaction of fluids with solids or other fluids at the boundaries (Fig.1.1.). Fluid mechanics is the branch of physics which involves the study of fluids (liquids, gases, and plasmas) and the forces on them. Fluid mechanics can be divided into two. a)Fluid Statics b)Fluid Dynamics Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies fluids at rest. It embraces the study of the conditions under which fluids are at rest in stable equilibrium Hydrostatics is fundamental to hydraulics, the engineering of equipment for storing, transporting and using fluids. Hydrostatics offers physical explanations for many phenomena of everyday life, such as why atmospheric pressure changes with altitude, why wood and oil float on water, and why the surface of water is always flat and horizontal whatever the shape of its container. Fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that deals with fluid flow— the natural science of fluids (liquids and gases) in motion. It has several subdisciplines itself, including aerodynamics (the study of air and other gases in motion) and hydrodynamics (the study of liquids in motion). -

Aerodynamics Material - Taylor & Francis

CopyrightAerodynamics material - Taylor & Francis ______________________________________________________________________ 257 Aerodynamics Symbol List Symbol Definition Units a speed of sound ⁄ a speed of sound at sea level ⁄ A area aspect ratio ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ b wing span c chord length c Copyrightmean aerodynamic material chord- Taylor & Francis specific heat at constant pressure of air · root chord tip chord specific heat at constant volume of air · / quarter chord total drag coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , induced drag coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , parasite drag coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , wave drag coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ local skin friction coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ lift coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , compressible lift coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ compressible moment ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , coefficient , pitching moment coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , rolling moment coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , yawing moment coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ______________________________________________________________________ 258 Aerodynamics Aerodynamics Symbol List (cont.) Symbol Definition Units pressure coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ compressible pressure ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , coefficient , critical pressure coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ , supersonic pressure coefficient ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ D total drag induced drag Copyright material - Taylor & Francis parasite drag e span efficiency factor ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ L lift pitching moment · rolling moment · yawing moment · M mach number ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ critical mach number ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ free stream mach number ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ P static pressure ⁄ total pressure ⁄ free stream pressure ⁄ q dynamic pressure ⁄ R -

Glossary: Definitions

Appendix B Glossary: Definitions The definitions given here apply to the terminology used throughout this book. Some of the terms may be defined differently by other authors; when this is the case, alternative terminology is noted. When two or more terms with identical or similar meaning are in general acceptance, they are given in the order of preference of the current writers. Allowable stress (working stress): If a member is so designed that the maximum stress as calculated for the expected conditions of service is less than some limiting value, the member will have a proper margin of security against damage or failure. This limiting value is the allowable stress subject to the material and condition of service in question. The allowable stress is made less than the damaging stress because of uncertainty as to the conditions of service, nonuniformity of material, and inaccuracy of the stress analysis (see Ref. 1). The margin between the allowable stress and the damaging stress may be reduced in proportion to the certainty with which the conditions of the service are known, the intrinsic reliability of the material, the accuracy with which the stress produced by the loading can be calculated, and the degree to which failure is unattended by danger or loss. (Compare with Damaging stress; Factor of safety; Factor of utilization; Margin of safety. See Refs. l–3.) Apparent elastic limit (useful limit point): The stress at which the rate of change of strain with respect to stress is 50% greater than at zero stress. It is more definitely determinable from the stress–strain diagram than is the proportional limit, and is useful for comparing materials of the same general class. -

Fluid Mechanics

cen72367_fm.qxd 11/23/04 11:22 AM Page i FLUID MECHANICS FUNDAMENTALS AND APPLICATIONS cen72367_fm.qxd 11/23/04 11:22 AM Page ii McGRAW-HILL SERIES IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING Alciatore and Histand: Introduction to Mechatronics and Measurement Systems Anderson: Computational Fluid Dynamics: The Basics with Applications Anderson: Fundamentals of Aerodynamics Anderson: Introduction to Flight Anderson: Modern Compressible Flow Barber: Intermediate Mechanics of Materials Beer/Johnston: Vector Mechanics for Engineers Beer/Johnston/DeWolf: Mechanics of Materials Borman and Ragland: Combustion Engineering Budynas: Advanced Strength and Applied Stress Analysis Çengel and Boles: Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach Çengel and Cimbala: Fluid Mechanics: Fundamentals and Applications Çengel and Turner: Fundamentals of Thermal-Fluid Sciences Çengel: Heat Transfer: A Practical Approach Crespo da Silva: Intermediate Dynamics Dieter: Engineering Design: A Materials & Processing Approach Dieter: Mechanical Metallurgy Doebelin: Measurement Systems: Application & Design Dunn: Measurement & Data Analysis for Engineering & Science EDS, Inc.: I-DEAS Student Guide Hamrock/Jacobson/Schmid: Fundamentals of Machine Elements Henkel and Pense: Structure and Properties of Engineering Material Heywood: Internal Combustion Engine Fundamentals Holman: Experimental Methods for Engineers Holman: Heat Transfer Hsu: MEMS & Microsystems: Manufacture & Design Hutton: Fundamentals of Finite Element Analysis Kays/Crawford/Weigand: Convective Heat and Mass Transfer Kelly: Fundamentals -

Aerospace Engine Data

AEROSPACE ENGINE DATA Data for some concrete aerospace engines and their craft ................................................................................. 1 Data on rocket-engine types and comparison with large turbofans ................................................................... 1 Data on some large airliner engines ................................................................................................................... 2 Data on other aircraft engines and manufacturers .......................................................................................... 3 In this Appendix common to Aircraft propulsion and Space propulsion, data for thrust, weight, and specific fuel consumption, are presented for some different types of engines (Table 1), with some values of specific impulse and exit speed (Table 2), a plot of Mach number and specific impulse characteristic of different engine types (Fig. 1), and detailed characteristics of some modern turbofan engines, used in large airplanes (Table 3). DATA FOR SOME CONCRETE AEROSPACE ENGINES AND THEIR CRAFT Table 1. Thrust to weight ratio (F/W), for engines and their crafts, at take-off*, specific fuel consumption (TSFC), and initial and final mass of craft (intermediate values appear in [kN] when forces, and in tonnes [t] when masses). Engine Engine TSFC Whole craft Whole craft Whole craft mass, type thrust/weight (g/s)/kN type thrust/weight mini/mfin Trent 900 350/63=5.5 15.5 A380 4×350/5600=0.25 560/330=1.8 cruise 90/63=1.4 cruise 4×90/5000=0.1 CFM56-5A 110/23=4.8 16 -

Bending Stress

Bending Stress Sign convention The positive shear force and bending moments are as shown in the figure. Figure 40: Sign convention followed. Centroid of an area Scanned by CamScanner If the area can be divided into n parts then the distance Y¯ of the centroid from a point can be calculated using n ¯ Âi=1 Aiy¯i Y = n Âi=1 Ai where Ai = area of the ith part, y¯i = distance of the centroid of the ith part from that point. Second moment of area, or moment of inertia of area, or area moment of inertia, or second area moment For a rectangular section, moments of inertia of the cross-sectional area about axes x and y are 1 I = bh3 x 12 Figure 41: A rectangular section. 1 I = hb3 y 12 Scanned by CamScanner Parallel axis theorem This theorem is useful for calculating the moment of inertia about an axis parallel to either x or y. For example, we can use this theorem to calculate . Ix0 = + 2 Ix0 Ix Ad Bending stress Bending stress at any point in the cross-section is My s = − I where y is the perpendicular distance to the point from the centroidal axis and it is assumed +ve above the axis and -ve below the axis. This will result in +ve sign for bending tensile (T) stress and -ve sign for bending compressive (C) stress. Largest normal stress Largest normal stress M c M s = | |max · = | |max m I S where S = section modulus for the beam. For a rectangular section, the moment of inertia of the cross- 1 3 1 2 sectional area I = 12 bh , c = h/2, and S = I/c = 6 bh . -

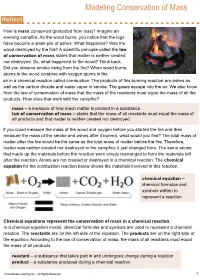

Modeling Conservation of Mass

Modeling Conservation of Mass How is mass conserved (protected from loss)? Imagine an evening campfire. As the wood burns, you notice that the logs have become a small pile of ashes. What happened? Was the wood destroyed by the fire? A scientific principle called the law of conservation of mass states that matter is neither created nor destroyed. So, what happened to the wood? Think back. Did you observe smoke rising from the fire? When wood burns, atoms in the wood combine with oxygen atoms in the air in a chemical reaction called combustion. The products of this burning reaction are ashes as well as the carbon dioxide and water vapor in smoke. The gases escape into the air. We also know from the law of conservation of mass that the mass of the reactants must equal the mass of all the products. How does that work with the campfire? mass – a measure of how much matter is present in a substance law of conservation of mass – states that the mass of all reactants must equal the mass of all products and that matter is neither created nor destroyed If you could measure the mass of the wood and oxygen before you started the fire and then measure the mass of the smoke and ashes after it burned, what would you find? The total mass of matter after the fire would be the same as the total mass of matter before the fire. Therefore, matter was neither created nor destroyed in the campfire; it just changed form. The same atoms that made up the materials before the reaction were simply rearranged to form the materials left after the reaction. -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Potential Flow Theory

2.016 Hydrodynamics Reading #4 2.016 Hydrodynamics Prof. A.H. Techet Potential Flow Theory “When a flow is both frictionless and irrotational, pleasant things happen.” –F.M. White, Fluid Mechanics 4th ed. We can treat external flows around bodies as invicid (i.e. frictionless) and irrotational (i.e. the fluid particles are not rotating). This is because the viscous effects are limited to a thin layer next to the body called the boundary layer. In graduate classes like 2.25, you’ll learn how to solve for the invicid flow and then correct this within the boundary layer by considering viscosity. For now, let’s just learn how to solve for the invicid flow. We can define a potential function,!(x, z,t) , as a continuous function that satisfies the basic laws of fluid mechanics: conservation of mass and momentum, assuming incompressible, inviscid and irrotational flow. There is a vector identity (prove it for yourself!) that states for any scalar, ", " # "$ = 0 By definition, for irrotational flow, r ! " #V = 0 Therefore ! r V = "# ! where ! = !(x, y, z,t) is the velocity potential function. Such that the components of velocity in Cartesian coordinates, as functions of space and time, are ! "! "! "! u = , v = and w = (4.1) dx dy dz version 1.0 updated 9/22/2005 -1- ©2005 A. Techet 2.016 Hydrodynamics Reading #4 Laplace Equation The velocity must still satisfy the conservation of mass equation. We can substitute in the relationship between potential and velocity and arrive at the Laplace Equation, which we will revisit in our discussion on linear waves. -

6. Chemical-Nuclear Propulsion MAE 342 2016

2/12/20 Chemical/Nuclear Propulsion Space System Design, MAE 342, Princeton University Robert Stengel • Thermal rockets • Performance parameters • Propellants and propellant storage Copyright 2016 by Robert Stengel. All rights reserved. For educational use only. http://www.princeton.edu/~stengel/MAE342.html 1 1 Chemical (Thermal) Rockets • Liquid/Gas Propellant –Monopropellant • Cold gas • Catalytic decomposition –Bipropellant • Separate oxidizer and fuel • Hypergolic (spontaneous) • Solid Propellant ignition –Mixed oxidizer and fuel • External ignition –External ignition • Storage –Burn to completion – Ambient temperature and pressure • Hybrid Propellant – Cryogenic –Liquid oxidizer, solid fuel – Pressurized tank –Throttlable –Throttlable –Start/stop cycling –Start/stop cycling 2 2 1 2/12/20 Cold Gas Thruster (used with inert gas) Moog Divert/Attitude Thruster and Valve 3 3 Monopropellant Hydrazine Thruster Aerojet Rocketdyne • Catalytic decomposition produces thrust • Reliable • Low performance • Toxic 4 4 2 2/12/20 Bi-Propellant Rocket Motor Thrust / Motor Weight ~ 70:1 5 5 Hypergolic, Storable Liquid- Propellant Thruster Titan 2 • Spontaneous combustion • Reliable • Corrosive, toxic 6 6 3 2/12/20 Pressure-Fed and Turbopump Engine Cycles Pressure-Fed Gas-Generator Rocket Rocket Cycle Cycle, with Nozzle Cooling 7 7 Staged Combustion Engine Cycles Staged Combustion Full-Flow Staged Rocket Cycle Combustion Rocket Cycle 8 8 4 2/12/20 German V-2 Rocket Motor, Fuel Injectors, and Turbopump 9 9 Combustion Chamber Injectors 10 10 5 2/12/20 -

Introduction to Compressible Computational Fluid Dynamics James S

Introduction to Compressible Computational Fluid Dynamics James S. Sochacki Department of Mathematics James Madison University [email protected] Abstract This document is intended as an introduction to computational fluid dynamics at the upper undergraduate level. It is assumed that the student has had courses through three dimensional calculus and some computer programming experience with numer- ical algorithms. A course in differential equations is recommended. This document is intended to be used by undergraduate instructors and students to gain an under- standing of computational fluid dynamics. The document can be used in a classroom or research environment at the undergraduate level. The idea of this work is to have the students use the modules to discover properties of the equations and then relate this to the physics of fluid dynamics. Many issues, such as rarefactions and shocks are left out of the discussion because the intent is to have the students discover these concepts and then study them with the instructor. The document is used in part of the undergraduate MATH 365 - Computation Fluid Dynamics course at James Madi- son University (JMU) and is part of the joint NSF Grant between JMU and North Carolina Central University (NCCU): A Collaborative Computational Sciences Pro- gram. This document introduces the full three-dimensional Navier Stokes equations. As- sumptions to these equations are made to derive equations that are accessible to un- dergraduates with the above prerequisites. These equations are approximated using finite difference methods. The development of the equations and finite difference methods are contained in this document. Software modules and their corresponding documentation in Fortran 90, Maple and Matlab can be downloaded from the web- site: http://www.math.jmu.edu/~jim/compressible.html. -

Lecture 1: Introduction

Lecture 1: Introduction E. J. Hinch Non-Newtonian fluids occur commonly in our world. These fluids, such as toothpaste, saliva, oils, mud and lava, exhibit a number of behaviors that are different from Newtonian fluids and have a number of additional material properties. In general, these differences arise because the fluid has a microstructure that influences the flow. In section 2, we will present a collection of some of the interesting phenomena arising from flow nonlinearities, the inhibition of stretching, elastic effects and normal stresses. In section 3 we will discuss a variety of devices for measuring material properties, a process known as rheometry. 1 Fluid Mechanical Preliminaries The equations of motion for an incompressible fluid of unit density are (for details and derivation see any text on fluid mechanics, e.g. [1]) @u + (u · r) u = r · S + F (1) @t r · u = 0 (2) where u is the velocity, S is the total stress tensor and F are the body forces. It is customary to divide the total stress into an isotropic part and a deviatoric part as in S = −pI + σ (3) where tr σ = 0. These equations are closed only if we can relate the deviatoric stress to the velocity field (the pressure field satisfies the incompressibility condition). It is common to look for local models where the stress depends only on the local gradients of the flow: σ = σ (E) where E is the rate of strain tensor 1 E = ru + ruT ; (4) 2 the symmetric part of the the velocity gradient tensor. The trace-free requirement on σ and the physical requirement of symmetry σ = σT means that there are only 5 independent components of the deviatoric stress: 3 shear stresses (the off-diagonal elements) and 2 normal stress differences (the diagonal elements constrained to sum to 0).