Chandra Observations of Abell 2261 Brightest Cluster Galaxy, a Candidate Host to a Recoiling Black Hole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Search for Transiting Extrasolar Planets in the Open Cluster NGC 4755

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Jayawardene, Bandupriya S. (2015) A search for transiting extrasolar planets in the open cluster NGC 4755. DAstron thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/41511/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/41511/ A SEARCH FOR TRANSITING EXTRASOLAR PLANETS IN THE OPEN CLUSTER NGC 4755 by Bandupriya S. Jayawardene A thesis submitted in satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Astronomy in the Faculty of Science, Technology and Engineering June 2015 James Cook University Townsville - Australia i STATEMENT OF ACCESS I the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Thesis network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. 2 STATEMENT OF SOURCES DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any University or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and list of references is given. -

A RADIO RELIC and a SEARCH for the CENTRAL BLACK HOLE in the ABELL 2261 BRIGHTEST CLUSTER GALAXY Sarah Burke-Spolaor1,2,3,4 Kayhan Gultekin¨ 5, Marc Postman6, Tod R

Faculty Scholarship 2017 A Radio Relic And A Search For The eC ntral Black Hole In The Abell 2261 Brightest Cluster Galaxy Sarah Burke-Spolaor Kayhan Gültekin Marc Postman Tod R. Lauer Joanna M. Taylor See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications Digital Commons Citation Burke-Spolaor, Sarah; Gültekin, Kayhan; Postman, Marc; Lauer, Tod R.; Taylor, Joanna M.; Lazio, T. Joseph W.; and Moustakas, Leonidas A., "A Radio Relic And A Search For The eC ntral Black Hole In The Abell 2261 Brightest Cluster Galaxy" (2017). Faculty Scholarship. 448. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications/448 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Sarah Burke-Spolaor, Kayhan Gültekin, Marc Postman, Tod R. Lauer, Joanna M. Taylor, T. Joseph W. Lazio, and Leonidas A. Moustakas This article is available at The Research Repository @ WVU: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/faculty_publications/448 Draft version September 5, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 A RADIO RELIC AND A SEARCH FOR THE CENTRAL BLACK HOLE IN THE ABELL 2261 BRIGHTEST CLUSTER GALAXY Sarah Burke-Spolaor1,2,3,4 Kayhan Gultekin¨ 5, Marc Postman6, Tod R. Lauer7, Joanna M. Taylor6, T. Joseph W. Lazio8, and Leonidas A. Moustakas8 Draft version September 5, 2018 ABSTRACT We present VLA images and HST/STIS spectra of sources within the center of the brightest cluster galaxy (BCG) in Abell 2261. -

A BRIGHTEST CLUSTER GALAXY with an EXTREMELY LARGE FLAT CORE Marc Postman1, Tod R

Accepted for publication in the The Astrophysical Journal, 24 July 2012 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 8/13/10 A BRIGHTEST CLUSTER GALAXY WITH AN EXTREMELY LARGE FLAT CORE Marc Postman1, Tod R. Lauer2, Megan Donahue3, Genevieve Graves4, Dan Coe1, John Moustakas5,6, Anton Koekemoer1, Larry Bradley1, Holland C. Ford7, Claudio Grillo8, Adi Zitrin9, Doron Lemze7, Tom Broadhurst10,11, Leonidas Moustakas12, Begona~ Ascaso13, Elinor Medezinski7, & Daniel Kelson14 Accepted for publication in the The Astrophysical Journal, 24 July 2012 ABSTRACT Hubble Space Telescope images of the galaxy cluster Abell 2261, obtained as part of the Cluster Lensing And Supernova survey with Hubble, show that the brightest galaxy in the cluster, A2261- BCG, has the largest core yet detected in any galaxy. The cusp radius of A2261-BCG is 3.2 kpc, twice as big as the next largest core known, and ∼ 3× bigger than those typically seen in the most luminous BCGs. The morphology of the core in A2261-BCG is also unusual, having a completely flat interior surface brightness profile, rather than the typical shallow cusp rising into the center. This implies that the galaxy has a core with constant or even centrally decreasing stellar density. Interpretation of the core as an end product of the \scouring" action of a binary supermassive black hole implies a total 10 black hole mass ∼ 10 M from the extrapolation of most relationships between core structure and black hole mass. The core falls 1σ above the cusp-radius versus galaxy luminosity relation. Its large size in real terms, and the extremely large black hole mass required to generate it, raise the possibility that the core has been enlarged by additional processes, such as the ejection of the black holes that originally generated the core. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

WTS-1 B: the first Extrasolar Planet Detected in the WFCAM Transit Survey

WTS-1 b: the first extrasolar planet detected in the WFCAM Transit Survey Michele Cappetta M¨unchen2012 WTS-1 b: the first extrasolar planet detected in the WFCAM Transit Survey Michele Cappetta Dissertation an der Fakult¨atf¨urPhysik der Ludwig{Maximilians{Universit¨at M¨unchen vorgelegt von Michele Cappetta aus Bolzano, Italien M¨unchen, den 19. Dezember 2012 Erstgutachter: R. P. Saglia Zweitgutachter: B. Ercolano Tag der m¨undlichen Pr¨ufung:5. Februar 2013 Contents Zusammenfassung xix Summary xxi 1 Extrasolar planets 1 1.1 Introduction . .2 1.2 Detection methods . .4 1.3 Planet formation . .7 1.3.1 The Solar Nebular Model . .7 1.3.2 Rocky planets formation . .8 1.3.3 Gas-giant planets formation . 10 1.4 Planet evolution . 13 1.4.1 Gas disk migration . 13 1.4.2 Planetesimal-driven migration . 14 1.4.3 Planet-planet scattering . 16 1.5 Extrasolar planets properties . 17 1.5.1 Radius anomaly of the hot-Jupiters . 22 2 WFCAM Transit Survey 25 2.1 Observing strategy . 27 2.2 Reduction pipeline . 29 2.3 Transit detection algorithm . 32 2.4 Transit recovery ratios . 34 2.5 Results . 37 3 Instrumentation and spectroscopic observations 39 3.1 Hobby-Eberly Telescope . 40 3.2 The HRS Spectrograph . 42 3.3 Instrumental configurations . 46 3.4 Visit types . 49 4 Reduction and analysis pipeline 51 4.1 Introduction . 52 vi CONTENTS 4.2 Data reduction . 54 4.2.1 Cosmic-rays filtering . 54 4.2.2 Frames calibration . 54 4.2.3 Apertures definition . 55 4.2.4 Spectra extraction . -

Report of Contracting Activity

Vendor Name Address Vendor Contact Vendor Phone Email Address Total Amount 1213 U STREET LLC /T/A BEN'S 1213 U ST., NW WASHINGTON DC 20009 VIRGINIA ALI 202-667-909 $3,181.75 350 ROCKWOOD DRIVE SOUTHINGTON CT 13TH JUROR, LLC 6489 REGINALD F. ALLARD, JR. 860-621-1013 $7,675.00 1417 N STREET NWCOOPERATIVE 1417 N ST NW COOPERATIVE WASHINGTON DC 20005 SILVIA SALAZAR 202-412-3244 $156,751.68 1133 15TH STREET NW, 12TH FL12TH FLOOR 1776 CAMPUS, INC. WASHINGTON DC 20005 BRITTANY HEYD 703-597-5237 [email protected] $200,000.00 6230 3rd Street NWSuite 2 Washington DC 1919 Calvert Street LLC 20011 Cheryl Davis 202-722-7423 $1,740,577.50 4606 16TH STREET, NW WASHINGTON DC 19TH STREET BAPTIST CHRUCH 20011 ROBIN SMITH 202-829-2773 $3,200.00 2013 H ST NWSTE 300 WASHINGTON DC 2013 HOLDINGS, INC 20006 NANCY SOUTHERS 202-454-1220 $5,000.00 3900 MILITARY ROAD NW WASHINGTON DC 202 COMMUNICATIONS INC. 20015 MIKE HEFFNER 202-244-8700 [email protected] $31,169.00 1010 NW 52ND TERRACEPO BOX 8593 TOPEAK 20-20 CAPTIONING & REPORTING KS 66608 JEANETTE CHRISTIAN 785-286-2730 [email protected] $3,120.00 21C3 LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT LL 11 WATERFORD CIRCLE HAMPTON VA 23666 KIPP ROGERS 757-503-5559 [email protected] $9,500.00 1816 12TH STREET NW WASHINGTON DC 21ST CENTURY SCHOOL FUND 20009 MARY FILARDO 202-745-3745 [email protected] $303,200.00 1550 CATON CENTER DRIVE, 21ST CENTURY SECURITY, LLC #ADBA/PROSHRED SECURITY BALTIMORE MD C. MARTIN FISHER 410-242-9224 $14,326.25 22 Atlantic Street CoOp 22 Atlantic Street SE Washington DC 20032 LaVerne Grant 202-409-1813 $2,899,682.00 11701 BOWMAN GREEN DRIVE RESTON VA 2228 MLK LLC 20190 CHRIS GAELER 703-581-6109 $218,182.28 1651 Old Meadow RoadSuite 305 McLean VA 2321 4th Street LLC 22102 Jim Edmondson 703-893-303 $13,612,478.00 722 12TH STREET NWFLOOR 3 WASHINGTON 270 STRATEGIES INC DC 20005 LENORA HANKS 312-618-1614 [email protected] $60,000.00 2ND LOGIC, LLC 10405 OVERGATE PLACE POTOMAC MD 20854 REZA SAFAMEJAD 202-827-7420 [email protected] $58,500.00 3119 Martin Luther King Jr. -

Astrobiology Math

National Aeronautics andSpace Administration Aeronautics National Astrobiology Math This collection of activities is based on a weekly series of space science problems intended for students looking for additional challenges in the math and physical science curriculum in grades 6 through 12. The problems were created to be authentic glimpses of modern science and engineering issues, often involving actual research data. The problems were designed to be one-pagers with a Teacher’s Guide and Answer Key as a second page. This compact form was deemed very popular by participating teachers. Astrobiology Math Mathematical Problems Featuring Astrobiology Applications Dr. Sten Odenwald NASA / ADNET Corp. [email protected] Astrobiology Math i http://spacemath.gsfc.nasa.gov Acknowledgments: We would like to thank Ms. Daniella Scalice for her boundless enthusiasm in the review and editing of this resource. Ms. Scalice is the Education and Public Outreach Coordinator for the NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI) at the Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. We would also like to thank the team of educators and scientists at NAI who graciously read through the first draft of this book and made numerous suggestions for improving it and making it more generally useful to the astrobiology education community: Dr. Harold Geller (George Mason University), Dr. James Kratzer (Georgia Institute of Technology; Doyle Laboratory) and Ms. Suzi Taylor (Montana State University), For more weekly classroom activities about astronomy and space visit the Space Math@ NASA website, http://spacemath.gsfc.nasa.gov Image Credits: Front Cover: Collage created by Julie Fletcher (NAI), molecule image created by Jenny Mottar, NASA HQ. -

Diffuse Radio Emission from Galaxy Clusters

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Diffuse Radio Emission from Galaxy Clusters R. J. van Weeren · F. de Gasperin · H. Akamatsu · M. Br¨uggen · L. Feretti · H. Kang · A. Stroe · F. Zandanel Received: date / Accepted: date Abstract In a growing number of galaxy clusters dif- ICM. Cluster radio shocks (relics) are polarized sources fuse extended radio sources have been found. These mostly found in the cluster's periphery. They trace sources are not directly associated with individual clus- merger induced shock waves. Revived fossil plasma ter galaxies. The radio emission reveal the presence sources are characterized by their radio steep-spectra of cosmic rays and magnetic fields in the intracluster and often irregular morphologies. In this review we medium (ICM). We classify diffuse cluster radio sources give an overview of the properties of diffuse cluster ra- into radio halos, cluster radio shocks (relics), and re- dio sources, with an emphasis on recent observational vived AGN fossil plasma sources. Radio halo sources results. We discuss the resulting implications for the can be further divided into giant halos, mini-halos, underlying physical acceleration processes that oper- and possible \intermediate" sources. Halos are gener- ate in the ICM, the role of relativistic fossil plasma, ally positioned at cluster center and their brightness and the properties of ICM shocks and magnetic fields. approximately follows the distribution of the thermal We also compile an updated list of diffuse cluster ra- dio sources which will be available on-line (http:// galaxyclusters.com). We end this review with a dis- R. J. van Weeren cussion on the detection of diffuse radio emission from Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 the cosmic web. -

The Peculiar Motions of Early-Type Galaxies in Two Distant Regions. I

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons Dartmouth Scholarship Faculty Work 9-1996 The Peculiar Motions of Early-Type Galaxies in Two Distant Regions. I. Cluster and Galaxy Selection Gary Wegner Dartmouth College Matthew Colless Australian National University Glenn Baggley University of Durham Roger L. Davies University of Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa Part of the External Galaxies Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Wegner, Gary; Colless, Matthew; Baggley, Glenn; and Davies, Roger L., "The Peculiar Motions of Early-Type Galaxies in Two Distant Regions. I. Cluster and Galaxy Selection" (1996). Dartmouth Scholarship. 2309. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/facoa/2309 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Work at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dartmouth Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 106:1-26,1996 September IW © 1996. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.SA .... THE PECULIAR MOTIONS OF EARLY-TYPE GALAXIES IN TWO DISTANT REGIONS. I. CLUSTER AND GALAXY SELECTION 96ApJS..106 Gary Wegner 19 Department of Physics and Astronomy, 6127 Wilder Laboratory, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755-3528 Matthew Colless Mount Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories, Australian National University, Weston Creek, ACT 2611, Australia Glenn Baggley and Roger L. Davies Department of Physics, University of Durham, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, England Edmund Bertschenger Department of Physics, MIT 6-207, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 David Burstein Department of Physics and Astronomy, Box 871054, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1504 Robert K. -

The President's Report

2005-2006 YEAR BOOK The President’s Report July 1, 2005 - June 30, 2006 CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON ISSN 0069-066X The 2005-2006 Carnegie Institution of Washington Year Book is printed with 100% vegetable-derived inks on 15% postconsumer recycled paper. Design by Tina Taylor, T2 Design Former Presidents Former Trustees Daniel C. Gilman, 1902–1904 Philip H. Abelson, 1978–2004 Caryl P. Haskins, 1949–1956, 1971-2001 William Church Osborn, 1927–1934 Robert S. Woodward, 1904–1920 Alexander Agassiz, 1904–1905 John Hay, 1902–1905 Walter H. Page, 1971–1979 John C. Merriam, 1921–1938 Robert O. Anderson, 1976–1983 Barklie McKee Henry, 1949–1966 James Parmelee, 1917–1931 Vannevar Bush, 1939–1955 Lord Ashby of Brandon, 1967–1974 Myron T. Herrick, 1915–1929 William Barclay Parsons, 1907–1932 Caryl P. Haskins, 1956–1971 J. Paul Austin, 1976–1978 Abram S. Hewitt, 1902–1903 Stewart Paton, 1916–1942 Philip H. Abelson, 1971–1978 George G. Baldwin, 1925–1927 William R. Hewlett, 1971–2001 Robert N. Pennoyer, 1968–1989 James D. Ebert, 1978–1987 Thomas Barbour, 1934–1946 Henry L. Higginson, 1902–1919 George W. Pepper, 1914–1919 Edward E. David, Jr. (Acting President, 1987–1988) James F. Bell, 1935–1961 Ethan A. Hitchcock, 1902–1909 Richard S. Perkins, 1959–2000 Maxine F. Singer, 1988–2002 John S. Billings, 1902–1913 Henry Hitchcock, 1902 John J. Pershing, 1930–1943 Michael E. Gellert (Acting President, Jan.–April 2003) Robert Woods Bliss, 1936–1962 Herbert Hoover, 1920–1949 Henning W. Prentis, Jr., 1942–1959 Amory H. Bradford, 1959–1972 William Wirt Howe, 1903–1909 Henry S. -

DSO List V2 Current

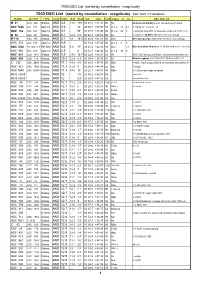

7000 DSO List (sorted by constellation - magnitude) 7000 DSO List (sorted by constellation - magnitude) - from SAC 7.7 database NAME OTHER TYPE CON MAG S.B. SIZE RA DEC U2K Class ns bs SAC NOTES M 31 NGC 224 Galaxy AND 3.4 13.5 189' 00 42.7 +41 16 60 Sb Andromeda Galaxy;Local Group;nearest spiral NGC 7686 OCL 251 Opn CL AND 5.6 - 15' 23 30.1 +49 08 88 IV 1 p 20 6.2 H VIII 69;12* mags 8...13 NGC 752 OCL 363 Opn CL AND 5.7 - 50' 01 57.7 +37 40 92 III 1 m 60 9 H VII 32;Best in RFT or binocs;Ir scattered cl 70* m 8... M 32 NGC 221 Galaxy AND 8.1 12.4 8.5' 00 42.7 +40 52 60 E2 Companion to M31; Member of Local Group M 110 NGC 205 Galaxy AND 8.1 14 19.5' 00 40.4 +41 41 60 SA0 M31 Companion;UGC 426; Member Local Group NGC 272 OCL 312 Opn CL AND 8.5 - 00 51.4 +35 49 90 IV 1 p 8 9 NGC 7662 PK 106-17.1 Pln Neb AND 8.6 5.6 17'' 23 25.9 +42 32 88 4(3) 14 Blue Snowball Nebula;H IV 18;Barnard-cent * variable? NGC 956 OCL 377 Opn CL AND 8.9 - 8' 02 32.5 +44 36 62 IV 1 p 30 9 NGC 891 UGC 1831 Galaxy AND 9.9 13.6 13.1' 02 22.6 +42 21 62 Sb NGC 1023 group;Lord Rosse drawing shows dark lane NGC 404 UGC 718 Galaxy AND 10.3 12.8 4.3' 01 09.4 +35 43 91 E0 Mirach's ghost H II 224;UGC 718;Beta AND sf 6' IC 239 UGC 2080 Galaxy AND 11.1 14.2 4.6' 02 36.5 +38 58 93 SBa In NGC 1023 group;vsBN in smooth bar;low surface br NGC 812 UGC 1598 Galaxy AND 11.2 12.8 3' 02 06.9 +44 34 62 Sbc Peculiar NGC 7640 UGC 12554 Galaxy AND 11.3 14.5 10' 23 22.1 +40 51 88 SBbc H II 600;nearly edge on spiral MCG +08-01-016 Galaxy AND 12 - 1.0' 23 59.2 +46 53 59 Face On MCG +08-01-018 -

Her – Objektauswahl NGC Teil 1

Her – Objektauswahl NGC Teil 1 NGC 6013 NGC 6044 NGC 6060 NGC 6098 NGC 6149 NGC 6166 NGC 6185 NGC 6210 NGC 6028 NGC 6045 NGC 6061 NGC 6099 NGC 6150 NGC 6168 NGC 6186 NGC 6212 NGC 6030 NGC 6047 NGC 6062 NGC 6106 NGC 6154 NGC 6173 NGC 6194 NGC 6219 NGC 6032 NGC 6050 NGC 6073 NGC 6113 NGC 6155 NGC 6174 NGC 6195 NGC 6224 Teil 2 NGC 6034 NGC 6052 NGC 6074 NGC 6132 NGC 6158 NGC 6175 NGC 6196 NGC 6225 Teil 3 NGC 6035 NGC 6054 NGC 6075 NGC 6141 NGC 6159 NGC 6177 NGC 6197 NGC 6228 NGC 6040 NGC 6055 NGC 6078 NGC 6145 NGC 6160 NGC 6179 NGC 6201 NGC 6229 NGC 6041 NGC 6056 NGC 6081 NGC 6146 NGC 6161 NGC 6180 NGC 6203 NGC 6230 NGC 6042 NGC 6057 NGC 6083 NGC 6147 NGC 6162 NGC 6181 NGC 6205 NGC 6233 NGC 6043 NGC 6058 NGC 6084 NGC 6148 NGC 6163 NGC 6184 NGC 6207 NGC 6239 Zur Objektauswahl: Nummer anklicken Sternbild- Zur Übersichtskarte: Objekt in Aufsuchkarte anklicken Übersicht Zum Detailfoto: Objekt in Übersichtskarte anklicken Her – Objektauswahl NGC Teil 2 NGC 6241 NGC 6270 NGC 6308 NGC 6329 NGC 6350 NGC 6389 NGC 6447 NGC 6490 NGC 6243 NGC 6271 NGC 6311 NGC 6330 NGC 6351 NGC 6408 NGC 6452 NGC 6495 Teil 1 NGC 6255 NGC 6272 NGC 6312 NGC 6332 NGC 6363 NGC 6417 NGC 6458 NGC 6500 NGC 6257 NGC 6274 NGC 6313 NGC 6336 NGC 6364 NGC 6427 NGC 6460 NGC 6501 NGC 6261 NGC 6276 NGC 6314 NGC 6339 NGC 6367 NGC 6429 NGC 6467 NGC 6504 Teil 3 NGC 6263 NGC 6278 NGC 6315 NGC 6341 NGC 6371 NGC 6430 NGC 6482 NGC 6513 NGC 6264 NGC 6279 NGC 6320 NGC 6343 NGC 6372 NGC 6433 NGC 6484 NGC 6518 NGC 6265 NGC 6282 NGC 6321 NGC 6347 NGC 6375 NGC 6442 NGC 6485 NGC 6524 NGC 6267 NGC