The Phylogeny of Hexapoda (Arthropoda) and the Evolution of Megadiversity Rolf G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Engineering of the Giant Dragonflies of the Permian: Revised Body Mass, Power, Air Supply, Thermoregulation and the Role of Air Density Alan E

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb185405. doi:10.1242/jeb.185405 COMMENTARY The engineering of the giant dragonflies of the Permian: revised body mass, power, air supply, thermoregulation and the role of air density Alan E. R. Cannell ABSTRACT abdomen as well as spiny and surprisingly robust legs. Illustrations An engineering examination of allometric and analogical data on the of M. monyi and a female Meganeurula selysii (Shear and flight of giant Permian insects (Protodonata, Meganeura or griffinflies) Kukalova-Peck, 1990) also indicate creatures with strong mouth indicates that previous estimates of the body mass of these insects parts, well-developed pincers and strong long thick legs. In both are too low and that the largest of these insects (wingspan of 70 cm or drawings, the abdomen is similar in diameter to the thorax, unlike more) would have had a mass of 100–150 g, several times greater the structure of most modern dragonflies, which have much more – – than previously thought. Here, the power needed to generate lift and slender abdomens. This large size and consequently high mass fly at the speeds typical of modern large dragonflies is examined has attracted attention for over a hundred years as there are no extant together with the metabolic rate and subsequent heat generated by insects of this size and their physiology in terms of power generation the thoracic muscles. This evaluation agrees with previous work and thermoregulation is not understood. This Commentary suggesting that the larger specimens would rapidly overheat in the examines the questions of mass, power generation to fly and high ambient temperatures assumed in the Permian. -

Fossil Record of Stem Groups Employed In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Fossil record of stem groups employed in evaluating the chronogram of insects (Arthropoda: Received: 07 April 2016 Accepted: 16 November 2016 Hexapoda) Published: 13 December 2016 Yan-hui Wang1,2,*, Michael S. Engel3,*, José A. Rafael4,*, Hao-yang Wu2, Dávid Rédei2, Qiang Xie2, Gang Wang1, Xiao-guang Liu1 & Wen-jun Bu2 Insecta s. str. (=Ectognatha), comprise the largest and most diversified group of living organisms, accounting for roughly half of the biodiversity on Earth. Understanding insect relationships and the specific time intervals for their episodes of radiation and extinction are critical to any comprehensive perspective on evolutionary events. Although some deeper nodes have been resolved congruently, the complete evolution of insects has remained obscure due to the lack of direct fossil evidence. Besides, various evolutionary phases of insects and the corresponding driving forces of diversification remain to be recognized. In this study, a comprehensive sample of all insect orders was used to reconstruct their phylogenetic relationships and estimate deep divergences. The phylogenetic relationships of insect orders were congruently recovered by Bayesian inference and maximum likelihood analyses. A complete timescale of divergences based on an uncorrelated log-normal relaxed clock model was established among all lineages of winged insects. The inferred timescale for various nodes are congruent with major historical events including the increase of atmospheric oxygen in the Late Silurian and earliest Devonian, the radiation of vascular plants in the Devonian, and with the available fossil record of the stem groups to various insect lineages in the Devonian and Carboniferous. Over half of all described living species are insects, and they dominate all terrestrial ecosystems1. -

Diplura and Protura of Canada

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 819: 197–203 (2019) Diplura and Protura of Canada 197 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.819.25238 REVIEW ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Diplura and Protura of Canada Derek S. Sikes1 1 University of Alaska Museum, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska 99775-6960, USA Corresponding author: Derek S. Sikes ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Langor | Received 23 March 2018 | Accepted 12 April 2018 | Published 24 January 2019 http://zoobank.org/D68D1C72-FF1D-4415-8E0F-28B36460E90A Citation: Sikes DS (2019) Diplura and Protura of Canada. In: Langor DW, Sheffield CS (Eds) The Biota of Canada – A Biodiversity Assessment. Part 1: The Terrestrial Arthropods. ZooKeys 819: 197–203.https://doi.org/10.3897/ zookeys.819.25238 Abstract A literature review of the Diplura and Protura of Canada is presented. Canada has six Diplura species documented and an estimated minimum 10–12 remaining to be documented. The Protura fauna is equally poorly known, with nine documented species and a conservatively estimated ten undocumented. Only six and three Barcode Index Numbers are available for Canadian specimens of Diplura and Protura, respectively. Keywords biodiversity assessment, Biota of Canada, Diplura, Protura Diplura, sometimes referred to as two-pronged bristletails, and Protura, sometimes called coneheads, are terrestrial arthropod taxa that have suffered from lack of scientific attention in Canada as well as globally. As both groups are undersampled and under- studied in Canada, the state of knowledge is considered to be poor, although there have been some modest advances since 1979. Both of these taxa are soil dwelling, and, given the repeated glaciations over most of Canada, the Canadian diversity is expected to be relatively low except possibly in unglaciated areas. -

Formation of the Entognathy of Dicellurata, Occasjapyx Japonicus (Enderlein, 1907) (Hexapoda: Diplura, Dicellurata)

S O I L O R G A N I S M S Volume 83 (3) 2011 pp. 399–404 ISSN: 1864-6417 Formation of the entognathy of Dicellurata, Occasjapyx japonicus (Enderlein, 1907) (Hexapoda: Diplura, Dicellurata) Kaoru Sekiya1, 2 and Ryuichiro Machida1 1 Sugadaira Montane Research Center, University of Tsukuba, Sugadaira Kogen, Ueda, Nagano 386-2204, Japan 2 Corresponding author: Kaoru Sekiya (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract The development of the entognathy in Dicellurata was examined using Occasjapyx japonicus (Enderlein, 1907). The formation of entognathy involves rotation of the labial appendages, resulting in a tandem arrangement of the glossa, paraglossa and labial palp. The mandibular, maxillary and labial terga extend ventrally to form the mouth fold. The intercalary tergum also participates in the formation of the mouth fold. The labial coxae extending anteriorly unite with the labial terga, constituting the posterior region of the mouth fold, the medial half of which is later partitioned into the admentum. The labial appendages of both sides migrate medially, and the labial subcoxae fuse to form the postmentum, which posteriorly confines the entognathy. The entognathy formation in Dicellurata is common to that in another dipluran suborder, Rhabdura. The entognathy of Diplura greatly differs from that of Protura and Collembola in the developmental plan, preventing homologization of the entognathies of Diplura and other two entognathan orders. Keywords: Entognatha, comparative embryology, mouth fold, admentum, postmentum 1. Introduction The Diplura, a basal clade of the Hexapoda, have traditionally been placed within Entognatha [= Diplura + Collembola + Protura], a group characterized by entognathy (Hennig 1969). However, Hennig’s ‘Entognatha-Ectognatha System’, especially the validity of Entognatha, has been challenged by various disciplines. -

Annotated Checklist of the Diplura (Hexapoda: Entognatha) of California

Zootaxa 3780 (2): 297–322 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3780.2.5 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:DEF59FEA-C1C1-4AC6-9BB0-66E2DE694DFA Annotated Checklist of the Diplura (Hexapoda: Entognatha) of California G.O. GRAENING1, YANA SHCHERBANYUK2 & MARYAM ARGHANDIWAL3 Department of Biological Sciences, California State University, Sacramento 6000 J Street, Sacramento, CA 95819-6077. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The first checklist of California dipluran taxa is presented with annotations. New state and county records are reported, as well as new taxa in the process of being described. California has a remarkable dipluran fauna with about 8% of global richness. California hosts 63 species in 5 families, with 51 of those species endemic to the State, and half of these endemics limited to single locales. The genera Nanojapyx, Hecajapyx, and Holjapyx are all primarily restricted to California. Two species are understood to be exotic, and six dubious taxa are removed from the State checklist. Counties in the central Coastal Ranges have the highest diversity of diplurans; this may indicate sampling bias. Caves and mines harbor unique and endemic dipluran species, and subterranean habitats should be better inventoried. Only four California taxa exhibit obvious troglomorphy and may be true cave obligates. In general, the North American dipluran fauna is still under-inven- toried. Since many taxa are morphologically uniform but genetically diverse, genetic analyses should be incorporated into future taxonomic descriptions. -

Animal Phylum Poster Porifera

Phylum PORIFERA CNIDARIA PLATYHELMINTHES ANNELIDA MOLLUSCA ECHINODERMATA ARTHROPODA CHORDATA Hexactinellida -- glass (siliceous) Anthozoa -- corals and sea Turbellaria -- free-living or symbiotic Polychaetes -- segmented Gastopods -- snails and slugs Asteroidea -- starfish Trilobitomorpha -- tribolites (extinct) Urochordata -- tunicates Groups sponges anemones flatworms (Dugusia) bristleworms Bivalves -- clams, scallops, mussels Echinoidea -- sea urchins, sand Chelicerata Cephalochordata -- lancelets (organisms studied in detail in Demospongia -- spongin or Hydrazoa -- hydras, some corals Trematoda -- flukes (parasitic) Oligochaetes -- earthworms (Lumbricus) Cephalopods -- squid, octopus, dollars Arachnida -- spiders, scorpions Mixini -- hagfish siliceous sponges Xiphosura -- horseshoe crabs Bio1AL are underlined) Cubozoa -- box jellyfish, sea wasps Cestoda -- tapeworms (parasitic) Hirudinea -- leeches nautilus Holothuroidea -- sea cucumbers Petromyzontida -- lamprey Mandibulata Calcarea -- calcareous sponges Scyphozoa -- jellyfish, sea nettles Monogenea -- parasitic flatworms Polyplacophora -- chitons Ophiuroidea -- brittle stars Chondrichtyes -- sharks, skates Crustacea -- crustaceans (shrimp, crayfish Scleropongiae -- coralline or Crinoidea -- sea lily, feather stars Actinipterygia -- ray-finned fish tropical reef sponges Hexapoda -- insects (cockroach, fruit fly) Sarcopterygia -- lobed-finned fish Myriapoda Amphibia (frog, newt) Chilopoda -- centipedes Diplopoda -- millipedes Reptilia (snake, turtle) Aves (chicken, hummingbird) Mammalia -

Two Remarkable Fossil Insect Larvae from Burmese Amber Suggest the Presence of a Terminal Filum in the Direct Stem Lineage of Dragonflies and Damselflies (Odonata)

Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy) vol. 126(1): 13-35. March 2020 TWO REMARKABLE FOSSIL INSECT LARVAE FROM BURMESE AMBER SUGGEST THE PRESENCE OF A TERMINAL FILUM IN THE DIRECT STEM LINEAGE OF DRAGONFLIES AND DAMSELFLIES (ODONATA) MARIO SCHÄDEL1*, PATRICK MÜLLER2 & JOACHIM T. HAUG1,3 1*Corresponding author. Department of Biology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Großhaderner Str. 2, 82152 Planegg-Martinsried, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2Friedhofstr. 9, 66894 Käshofen, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 3GeoBio-Center of the LMU Munich, Richard-Wagner-Str. 10, 80333 Munich, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] To cite this article: Schädel M., Müller P. & Haug J.T. (2020) - Two remarkable fossil insect larvae from Burmese amber suggest the presence of a terminal filum in the direct stem lineage of dragonflies and damselflies (Odonata). Riv. It. Paleontol. Strat., 126(1): 13-35. Keywords: character evolution; Cretaceous; moult; Myanmar; Odonatoptera; ontogeny. Abstract. The fossil record of dragonfly relatives (Odonatoptera) dates back to the Carboniferous, yet knowl- edge about these extinct animals is meagre. For most of the species little is known except for the characteristics of the wing venation. As a result, it is difficult to include fossil larvae in a (wing character based) phylogenetic tree as the wing venation is not visible in most of the larval instars. Two larval specimens from Cretaceous Burmese amber are in the focus of this study. The two specimens likely represent two subsequent early stage larval instars of the same individual. Not only is this an exceptional case to study ontogenetic processes in fossils – the larval instars are morphologically completely different from all known larvae of Odonata with respect to the posterior abdominal region. -

1 Biology 205: Partial Classification Of

[Leander – University of British Columbia] BIOLOGY 205: PARTIAL CLASSIFICATION OF INVERTEBRATES You are responsible for knowing the following taxa in bold font (Ranks are arbitrary & listed for pedagogical purposes) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Domain Eukaryota 1. Subdomain Excavata (Giardia, trichomonads, trypanosomatids, euglenids etc.) 2. Subdomain Rhizaria (forams, radiolarians, cercomonads, chlorarchniophytes etc.) 3. Subdomain Chromalveolata (brown algae, diatoms, ciliates, dinoflagellates etc.) 4. Subdomain Plantae (red algae, green algae, land plants etc.) 5. Subdomain Opisthokonta (animals, fungi, slime molds etc.) Superkingdom Amoebozoa (dictyostelids, myxomycetes, lobose amoebae etc.) Superkingdom Fungi (chytrids, mushrooms, yeasts etc.) Superkingdom Choanozoa Kingdom Choanoflagellata (choanoflagellates) ‘invertebrates’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ⇓ Kingdom Animalia (= Metazoa) Phylum Porifera (sponges) Class Calcarea (calcareous sponges) Class Hexactinellida (glass sponges) Class Demospongiae (demosponges) Phylum Placozoa (Trichoplax) Eumetazoa ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ⇓ Phylum Cnidaria (cnidarians) Class Hydrozoa (hydroids & hydromedusae) Class Anthozoa (anemones, corals & sea pens) Class Scyphozoa (‘true’ sea jellies) Phylum Myxozoa Phylum -

(Includes Insects) Myriapods Pycnogonids Limulids Arachnids

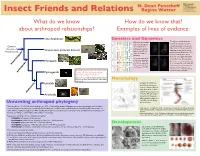

N. Dean Pentcheff Insect Friends and Relations Regina Wetzer What do we know How do we know that? about arthropod relationships? Examples of lines of evidence: Onychophorans Genetics and Genomics Genomic approaches The figures at left show the can look at patterns protein structure of opsins Common of occurrence of (visual pigments). Yellow iden- tifies areas of the protein that Ancestor of whole genes across Crustaceans (includes Insects) have important evolutionary Panarthropoda taxa to identify pat- terns of common and functional differences. This ancestry. provides information about how the opsin gene family has Cook, C. E., Smith, M. L., evolved across different taxa. Telford, M. J., Bastianello, Myriapods A., Akam, M. 2001. Hox Porter, M. L., Cronin, T. W., McClellan, Panarthropoda genes and the phylogeny D. A., Crandall, K. A. 2007. Molecular of the arthropods. Cur- characterization of crustacean visual rent Biology 11: 759-763. pigments and the evolution of pan- crustacean opsins. Molecular Biology This phylogenetic tree of the Arthropoda and Evolution 24(1): 253-268. Arthropoda Pycnogonids outlines our best current knowledge about relationships in the group. Dunn, C.W. et al. 2008. Broad phylogenetic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature Morphology 452: 745-749. Limulids Comparing similarities and differences among arthropod appendages is a fertile source of infor- Chelicerata mation about patterns of ancestry. Morphological Arachnids evidence can be espec- ially valuable because it is available for both living Unraveling arthropod phylogeny and fossil taxa. There are about 1,100,000 described arthropods – 85% of multicellular animals! Segmentation, jointed appendages, and the devel- opment of pattern-forming genes profoundly affected arthropod evolution and created the most morphologically diverse taxon on [Left:] Cotton, T. -

Phylogeny of Endopterygote Insects, the Most Successful Lineage of Living Organisms*

REVIEW Eur. J. Entomol. 96: 237-253, 1999 ISSN 1210-5759 Phylogeny of endopterygote insects, the most successful lineage of living organisms* N iels P. KRISTENSEN Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copenhagen 0, Denmark; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Insecta, Endopterygota, Holometabola, phylogeny, diversification modes, Megaloptera, Raphidioptera, Neuroptera, Coleóptera, Strepsiptera, Díptera, Mecoptera, Siphonaptera, Trichoptera, Lepidoptera, Hymenoptera Abstract. The monophyly of the Endopterygota is supported primarily by the specialized larva without external wing buds and with degradable eyes, as well as by the quiescence of the last immature (pupal) stage; a specialized morphology of the latter is not an en dopterygote groundplan trait. There is weak support for the basal endopterygote splitting event being between a Neuropterida + Co leóptera clade and a Mecopterida + Hymenoptera clade; a fully sclerotized sitophore plate in the adult is a newly recognized possible groundplan autapomorphy of the latter. The molecular evidence for a Strepsiptera + Díptera clade is differently interpreted by advo cates of parsimony and maximum likelihood analyses of sequence data, and the morphological evidence for the monophyly of this clade is ambiguous. The basal diversification patterns within the principal endopterygote clades (“orders”) are succinctly reviewed. The truly species-rich clades are almost consistently quite subordinate. The identification of “key innovations” promoting evolution -

Rasnitsynala Sigambrorum Gen. Et Sp. N., a Small Odonatopterid

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 130: 57–66 (2011)Rasnitsynala sigambrorum gen. et sp. n., a small odonatopterid... 57 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.130.1458 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Rasnitsynala sigambrorum gen. et sp. n., a small odonatopterid (“Eomeganisoptera”, “Erasipteridae”) from the early Late Carboniferous of Hagen-Vorhalle (Germany) Wolfgang Zessin1,†, Carsten Brauckmann2,‡, Elke Gröning2,§ 1 Lange Straße 9, 19230 Jasnitz, Germany 2 Clausthal University of Technology, Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Leibnizstraße 10, 38678 Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany † urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:EE854837-A2FB-457C-82F1-60406627EC58 ‡ urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A9B536B4-6DEF-48C4-980A-9EB8A9467F8B § urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D085012-9A15-4937-B408-FEFDF39B4907 Corresponding author: Wolfgang Zessin ([email protected]) Academic editor: D. Shcherbakov | Received 2 May 2011 | Accepted 26 August 2011 | Published 24 September 2011 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:708DBB4C-244E-4606-992B-D10129016158 Citation: Zessin W, Brauckmann C, Gröning E (2011) Rasnitsynala sigambrorum gen. et sp. n., a small odonatopterid (“Eomeganisoptera”, “Erasipteridae”) from the early Late Carboniferous of Hagen-Vorhalle (Germany). In: Shcherbakov DE, Engel MS, Sharkey MJ (Eds) Advances in the Systematics of Fossil and Modern Insects: Honouring Alexandr Rasnitsyn. ZooKeys 130: 57–66. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.130.1458 Abstract Besides Erasipteroides valentini (Brauckmann in Brauckmann, Koch & Kemper, 1985), Zessinella siope Brauckmann, 1988, and Namurotypus sippeli Brauckmann & Zessin, 1989, Rasnitsynala sigambrorum gen. et sp. n. is the fourth species of the Odonatoptera from the early Late Carboniferous (Early Penn- sylvanian: Namurian B, Marsdenian) deposits of the important Hagen-Vorhalle Konservat-Lagerstätte in Germany. -

A Tale of Two Analyses: Estimating the Consequences of Shifts in Hexapod Diversification

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society0024-4066The Linnean Society of London, 2003? 2003 801 2336 Original Article HEXAPOD DIVERSIFICATION P. J. MAYHEW Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2003, 80, 23–36. With 2 figures A tale of two analyses: estimating the consequences of shifts in hexapod diversification PETER J. MAYHEW Department of Biology, University of York, PO Box 373, York YO10 5YW, UK Received 2 September 2002; accepted for publication 31 January 2003 I present a novel descriptive (non-statistical) method to help identify the location and importance of shifts in diver- sification across a phylogeny. The method first estimates radiation rates across terminal higher taxa and then sub- jects these rates to a parsimony analysis across the phylogeny. The reconstructions define the magnitude, direction and influence of past shifts in realized diversification rates across nodes. I apply the method to data on the extant hexapod orders. The results indicate that the Coleoptera (beetles) and Diptera (flies) have contributed large upward shifts in diversification tendency, without which, under the model employed, global species richness would be reduced by 20% and 6%, respectively. The origin of Neoptera (insects with wing flexion), identified elsewhere as a sig- nificant radiation, may represent a large positive, a large negative or zero influence on current species richness, depending on the assumed phylogeny and parsimony method. The most influential radiations are attributable to the origin of the Eumetabola (insects with complete metamorphosis plus bugs and their relatives) and Pterygota (winged insects), but there is presently only weak evidence that they represent significant shifts in underlying diversification tendency.