Why Do We Call It A...Watt?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Diesel Engines

GENERAL ARTICLE The Evolution of Diesel Engines U Shrinivasa Rudolf Diesel thought of an engine which is inherently more efficient than the steam engines of the end-nineteenth century, for providing motive power in a distributed way. His intense perseverance, spread over a decade, led to the engines of today which bear his name. U Shrinivasa teaches Steam Engines: History vibrations and dynamics of machinery at the Department The origin of diesel engines is intimately related to the history of of Mechanical Engineering, steam engines. The Greeks and the Romans knew that steam IISc. His other interests include the use of straight could somehow be harnessed to do useful work. The device vegetable oils in diesel aeolipile (Figure 1) known to Hero of Alexandria was a primitive engines for sustainable reaction turbine apparently used to open temple doors! However development and working this aspect of obtaining power from steam was soon forgotten and with CAE applications in the industries. millennia later when there was a requirement for lifting water from coal mines, steam was introduced into a large vessel and quenched to create a low pressure for sucking the water to be pumped. Newcomen in 1710 introduced a cylinder piston ar- rangement and a hinged beam (Figure 2) such that water could be pumped from greater depths. The condensing steam in the cylin- der pulled the piston down to create the pumping action. Another half a century later, in 1765, James Watt avoided the cooling of the hot chamber containing steam by adding a separate condensing chamber (Figure 3). This successful steam engine pump found investors to manufacture it but the coal mines already had horses to lift the water to be pumped. -

MACHINES OR ENGINES, in GENERAL OR of POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, Eg STEAM ENGINES

F01B MACHINES OR ENGINES, IN GENERAL OR OF POSITIVE-DISPLACEMENT TYPE, e.g. STEAM ENGINES (of rotary-piston or oscillating-piston type F01C; of non-positive-displacement type F01D; internal-combustion aspects of reciprocating-piston engines F02B57/00, F02B59/00; crankshafts, crossheads, connecting-rods F16C; flywheels F16F; gearings for interconverting rotary motion and reciprocating motion in general F16H; pistons, piston rods, cylinders, for engines in general F16J) Definition statement This subclass/group covers: Machines or engines, in general or of positive-displacement type References relevant to classification in this subclass This subclass/group does not cover: Rotary-piston or oscillating-piston F01C type Non-positive-displacement type F01D Informative references Attention is drawn to the following places, which may be of interest for search: Internal combustion engines F02B Internal combustion aspects of F02B 57/00; F02B 59/00 reciprocating piston engines Crankshafts, crossheads, F16C connecting-rods Flywheels F16F Gearings for interconverting rotary F16H motion and reciprocating motion in general Pistons, piston rods, cylinders for F16J engines in general 1 Cyclically operating valves for F01L machines or engines Lubrication of machines or engines in F01M general Steam engine plants F01K Glossary of terms In this subclass/group, the following terms (or expressions) are used with the meaning indicated: In patent documents the following abbreviations are often used: Engine a device for continuously converting fluid energy into mechanical power, Thus, this term includes, for example, steam piston engines or steam turbines, per se, or internal-combustion piston engines, but it excludes single-stroke devices. Machine a device which could equally be an engine and a pump, and not a device which is restricted to an engine or one which is restricted to a pump. -

Building a Small Horizontal Steam Engine

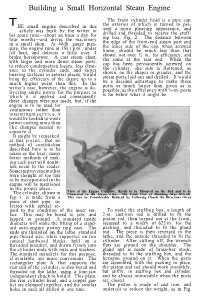

Building a Small Horizontal Steam Engine The front cylinder head is a pipe cap, THE small engine described in this the exterior of which is turned to pre- article was built by the writer in sent a more pleasing appearance, and his spare time—about an hour a day for drilled and threaded to receive the stuff- four months—and drives the machinery ing box, Fig. 2. The distance between in a small shop. At 40-lb. gauge pres- the edge of the front-end steam port and sure, the engine runs at 150 r.p.m., under the inner side of the cap, when screwed full load, and delivers a little over .4 home, should be much less than that brake horsepower. A cast steam chest, shown, not over ¼ in., for efficiency, and with larger and more direct steam ports, the same at the rear end. When the to reduce condensation losses; less clear- cap has been permanently screwed on ance in the cylinder ends, and larger the cylinder, one side is flattened, as bearing surfaces in several places, would shown, on the shaper or grinder, and the bring the efficiency of the engine up to a steam ports laid out and drilled. It would much higher point than this. In the be a decided advantage to make these writer's case, however, the engine is de- ports as much larger than given as is livering ample power for the purpose to possible, as the efficiency with ½-in. ports which it is applied, and consequently is far below what it might be. -

Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Robert Stirling

Stirling Stuff Dr John S. Reid, Department of Physics, Meston Building, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB12 3UE, Scotland Abstract Robert Stirling’s patent for what was essentially a new type of engine to create work from heat was submitted in 1816. Its reception was underwhelming and although the idea was sporadically developed, it was eclipsed by the steam engine and, later, the internal combustion engine. Today, though, the environmentally favourable credentials of the Stirling engine principles are driving a resurgence of interest, with modern designs using modern materials. These themes are woven through a historically based narrative that introduces Robert Stirling and his background, a description of his patent and the principles behind his engine, and discusses the now popular model Stirling engines readily available. These topical models, or alternatives made ‘in house’, form a good platform for investigating some of the thermodynamics governing the performance of engines in general. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Introduction 2016 marks the bicentenary of the submission of Robert Stirling’s patent that described heat exchangers and the technology of the Stirling engine. James Watt was still alive in 1816 and his steam engine was gaining a foothold in mines, in mills, in a few goods railways and even in pioneering ‘steamers’. Who needed another new engine from another Scot? The Stirling engine is a markedly different machine from either the earlier steam engine or the later internal combustion engine. For reasons to be explained, after a comparatively obscure two centuries the Stirling engine is attracting new interest, for it has environmentally friendly credentials for an engine. This tribute introduces the man, his patent, the engine and how it is realised in example models readily available on the internet. -

Champ Math Study Guide Indesign

Champions of Mathematics — Study Guide — Questions and Activities Page 1 Copyright © 2001 by Master Books, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced for educational purposes only. BY JOHN HUDSON TINER To get the most out of this book, the following is recommended: Each chapter has questions, discussion ideas, research topics, and suggestions for further reading to improve students’ reading, writing, and thinking skills. The study guide shows the relationship of events in Champions of Mathematics to other fields of learning. The book becomes a springboard for exploration in other fields. Students who enjoy literature, history, art, or other subjects will find interesting activities in their fields of interest. Parents will find that the questions and activities enhance their investments in the Champion books because children of different age levels can use them. The questions with answers are designed for younger readers. Questions are objective and depend solely on the text of the book itself. The questions are arranged in the same order as the content of each chapter. A student can enjoy the book and quickly check his or her understanding and comprehension by the challenge of answering the questions. The activities are designed to serve as supplemental material for older students. The activities require greater knowledge and research skills. An older student (or the same student three or four years later) can read the book and do the activities in depth. CHAPTER 1 QUESTIONS 1. A B C D — Pythagoras was born on an island in the (A. Aegean Sea B. Atlantic Ocean C. Caribbean Sea D. -

Steam As a General Purpose Technology: a Growth Accounting Perspective

Working Paper No. 75/03 Steam as a General Purpose Technology: A Growth Accounting Perspective Nicholas Crafts © Nicholas Crafts Department of Economic History London School of Economics May 2003 Department of Economic History London School of Economics Houghton Street London, WC2A 2AE Tel: +44 (0)20 7955 6399 Fax: +44 (0)20 7955 7730 1. Introduction* In recent years there has been an upsurge of interest among growth economists in General Purpose Technologies (GPTs). A GPT can be defined as "a technology that initially has much scope for improvement and evntually comes to be widely used, to have many uses, and to have many Hicksian and technological complementarities" (Lipsey et al., 1998a, p. 43). Electricity, steam and information and communications technologies (ICT) are generally regarded as being among the most important examples. An interesting aspect of the occasional arrival of new GPTs that dominate macroeconomic outcomes is that they imply that the growth process may be subject to episodes of sharp acceleration and deceleration. The initial impact of a GPT on overall productivity growth is typically minimal and the realization of its eventual potential may take several decades such that the largest growth effects are quite long- delayed, as with electricity in the early twentieth century (David, 1991). Subsequently, as the scope of the technology is finally exhausted, its impact on growth will fade away. If, at that point, a new GPT is yet to be discovered or only in its infancy, a growth slowdown might be observed. A good example of this is taken by the GPT literature to be the hiatus between steam and electricity in the later nineteenth century (Lipsey et al., 1998b), echoing the famous hypothesis first advanced by Phelps-Brown and Handfield-Jones, 1952) to explain the climacteric in British economic growth. -

An Atomic Physics Perspective on the New Kilogram Defined by Planck's Constant

An atomic physics perspective on the new kilogram defined by Planck’s constant (Wolfgang Ketterle and Alan O. Jamison, MIT) (Manuscript submitted to Physics Today) On May 20, the kilogram will no longer be defined by the artefact in Paris, but through the definition1 of Planck’s constant h=6.626 070 15*10-34 kg m2/s. This is the result of advances in metrology: The best two measurements of h, the Watt balance and the silicon spheres, have now reached an accuracy similar to the mass drift of the ur-kilogram in Paris over 130 years. At this point, the General Conference on Weights and Measures decided to use the precisely measured numerical value of h as the definition of h, which then defines the unit of the kilogram. But how can we now explain in simple terms what exactly one kilogram is? How do fixed numerical values of h, the speed of light c and the Cs hyperfine frequency νCs define the kilogram? In this article we give a simple conceptual picture of the new kilogram and relate it to the practical realizations of the kilogram. A similar change occurred in 1983 for the definition of the meter when the speed of light was defined to be 299 792 458 m/s. Since the second was the time required for 9 192 631 770 oscillations of hyperfine radiation from a cesium atom, defining the speed of light defined the meter as the distance travelled by light in 1/9192631770 of a second, or equivalently, as 9192631770/299792458 times the wavelength of the cesium hyperfine radiation. -

Steam and You! How Steam Engines Helped the United States to Expand Reading

Name____________________________________ Date ____________ Steam and You! How Steam Engines Helped The United States To Expand Reading How Is Steam Used To Help People? (Please fill in any blank spaces as you read) Have you ever observed steam, also known as water vapor? For centuries, people have observed steam and how it moves. Describe steam on the line below. Does it rise or fall?____________________________________________________________ Steam is _______ and it ___________. When lots of steam moves into a pipe, it creates pressure that can be used to move things. Inventors discovered about 300 years ago that they could use steam to power machines. These machines have transformed human life. Steam is used today to help power ships and to spin large turbines that generate electricity for millions of people throughout the world. The steam engine was one of the most important inventions of the Industrial Revolution that occurred about from about 1760 to 1840. The Industrial Revolution was a time when machine technology rapidly changed society. Steam engines were used to power train locomotives, steamboats, machines in factories, equipment in mines, and even automobiles before other kinds of engines were invented. Boiling water in a tea kettle produces A steamboat uses a steam engine to steam. Steam can power a steam engine. turn a paddlewheel to move the boat. A steam locomotive was powered when A steam turbine is a large metal cylinder coal or wood was burned inside it to boil with large fan blades that can spin when water to make steam. The steam steam flows through its blades. -

Steam Engine Use and Development

STEAM ENGINE USE AND DEVELOPMENT A diagram of Cameron's aero-steam engine, from an 1876 dictionary The first industrial applications of the vacuum engines were in the pumping of water from deep mineshafts. The Newcomen steam engine [[12]] operated by admitting steam to the operating chamber, closing the valve, and then admitting a spray of cold water. The water vapor condenses to a much smaller volume of water, creating a vacuum in the chamber. Atmospheric pressure, operating on the opposite side of a piston, pushes the piston to the bottom of the chamber. In mineshaft pumps, the piston was connected to an operating rod that descended the shaft to a pump chamber. The oscillations of the operating rod are transferred to a pump piston that moves the water, through check valves, to the top of the shaft. The first significant improvement, 60 years later, was creation of a separate condensing chamber with a valve between the operating chamber and the condensing chamber. This improvement was invented on Glasgow Green, Scotland by James Watt[[13]] and subsequently developed by him in Birmingham, England, to produce the Watt steam engine [[14]] with greatly increased efficiency. The next improvement was the replacement of manually operated valves with valves operated by the engine itself. In 1802 William Symington built the "first practical steamboat", and in 1807 Robert Fulton used the Watt steam engine to power the first commercially successful steamboat. Such early vacuum, or condensing, engines are severely limited in their efficiency but are relatively safe since the steam is at very low pressure and structural failure of the engine will be by inward collapse rather than an outward explosion. -

EM Waves, Ray Optics, Optical Instruments Mar

Gen. Phys. II Exam 3 - Chs. 24,25,26 - EM Waves, Ray Optics, Optical Instruments Mar. 26, 2018 Rec. Time Name For full credit, make your work clear. Show formulas used, essential steps, and results with correct units and significant figures. Points shown in parenthesis. For TF and MC, choose the best answer. OpenStax Ch. 24 - Electromagnetic Waves 1. (3) Which type of electromagnetic (EM) waves has the highest frequency in vacuum? a. x-rays. b. infrared. c. red light. d. blue light. e. ultraviolet. f. AM radio. g. all tie. 2. (3) An EM wave is traveling vertically upward with its magnetic field vector oscillating north-south. Its electric field vector is oscillating a. north-south. b. east-west. c. vertically up and down. 3. (3) The first physicist to confirm the generation and detection of EM waves by using LC oscillator circuits was a. Alexander Bell. b. James Watt. c. Andr´e-Marie Amp`ere. d. Heinrich Hertz. e. Carl Friedrich Gauss. 4. (3) TF In vacuum, electromagnetic waves of higher frequencies travel faster than lower frequencies. 5. (3) TF EM waves in vacuum can be considered to be transverse waves. 6. (3) TF Earth's ozone layer is important in blocking dangerous infrared light from the sun. 7. (3) Which physical effect did James Clerk Maxwell add into the equations of electromagnetism that carry his name, based on theoretical reasoning? a. changing magnetic fields produce electric fields. b. changing electric fields produce magnetic fields. c. moving electric charges produce magnetic fields. d. moving electric charges experience magnetic forces. -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions.