Youth During the American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeking a Forgotten History

HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar HARVARD AND SLAVERY Seeking a Forgotten History by Sven Beckert, Katherine Stevens and the students of the Harvard and Slavery Research Seminar About the Authors Sven Beckert is Laird Bell Professor of history Katherine Stevens is a graduate student in at Harvard University and author of the forth- the History of American Civilization Program coming The Empire of Cotton: A Global History. at Harvard studying the history of the spread of slavery and changes to the environment in the antebellum U.S. South. © 2011 Sven Beckert and Katherine Stevens Cover Image: “Memorial Hall” PHOTOGRAPH BY KARTHIK DONDETI, GRADUATE SCHOOL OF DESIGN, HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2 Harvard & Slavery introducTION n the fall of 2007, four Harvard undergradu- surprising: Harvard presidents who brought slaves ate students came together in a seminar room to live with them on campus, significant endow- Ito solve a local but nonetheless significant ments drawn from the exploitation of slave labor, historical mystery: to research the historical con- Harvard’s administration and most of its faculty nections between Harvard University and slavery. favoring the suppression of public debates on Inspired by Ruth Simmon’s path-breaking work slavery. A quest that began with fears of finding at Brown University, the seminar’s goal was nothing ended with a new question —how was it to gain a better understanding of the history of that the university had failed for so long to engage the institution in which we were learning and with this elephantine aspect of its history? teaching, and to bring closer to home one of the The following pages will summarize some of greatest issues of American history: slavery. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Lesson 4 Name: Classwork Date

Lesson 4 Name: Classwork Date: “Thanksgiving for the Repeal of the Stamp-Act” (Diary of John Adams, 1:316) 1765 1768 1770 The Stamp Act is repealed Soldiers are stationed The Boston Massacre in the colonies By 1770, 16,000 people lived in Boston. About 600 were soldiers of the British Army. They were called “lobsterbacks” by the townspeople because of the red coat they wore as part of their uniform. The soldiers and the people of Boston did not get along because the colonists thought the soldiers were sent to enforce laws they did not want and therefore limited their freedom. Some colonists did not believe the soldiers were sent for their protection. Several incidents that preceded the Boston Massacre on March 5th 1770: Event 1 On February 28, 1770, a mob of people formed outside a British tax collector’s house in Boston’s North End. This tax collector was also believed to be an informant for the British government. The protestors showed their anger by throwing rotten food, ice, and stones at the tax collector’s house as well as calling him names. The crowd was out of control. Suddenly, something flew through the window and hit the tax collector’s wife. Her husband grabbed the gun, which was unloaded and waived it out the window to warn the crowd. When they kept up, he loaded the gun and fired into the crowd. Christopher Seider, an eleven-year-old boy, was shot, and died later that evening. Read what John Adams wrote in his diary about the funeral for Christopher: Feb. -

Exploring Boston's Religious History

Exploring Boston’s Religious History It is impossible to understand Boston without knowing something about its religious past. The city was founded in 1630 by settlers from England, Other Historical Destinations in popularly known as Puritans, Downtown Boston who wished to build a model Christian community. Their “city on a hill,” as Governor Old South Church Granary Burying Ground John Winthrop so memorably 645 Boylston Street Tremont Street, next to Park Street put it, was to be an example to On the corner of Dartmouth and Church, all the world. Central to this Boylston Streets Park Street T Stop goal was the establishment of Copley T Stop Burial Site of Samuel Adams and others independent local churches, in which all members had a voice New North Church (Now Saint Copp’s Hill Burying Ground and worship was simple and Stephen’s) Hull Street participatory. These Puritan 140 Hanover Street Haymarket and North Station T Stops religious ideals, which were Boston’s North End Burial Site of the Mathers later embodied in the Congregational churches, Site of Old North Church King’s Chapel Burying Ground shaped Boston’s early patterns (Second Church) Tremont Street, next to King’s Chapel of settlement and government, 2 North Square Government Center T Stop as well as its conflicts and Burial Site of John Cotton, John Winthrop controversies. Not many John Winthrop's Home Site and others original buildings remain, of Near 60 State Street course, but this tour of Boston’s “old downtown” will take you to sites important to the story of American Congregationalists, to their religious neighbors, and to one (617) 523-0470 of the nation’s oldest and most www.CongregationalLibrary.org intriguing cities. -

Publishing Blackness: Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE publishing blackness publishing blackness Textual Constructions of Race Since 1850 George Hutchinson and John K. Young, editors The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2013 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Publishing blackness : textual constructions of race since 1850 / George Hutchinson and John Young, editiors. pages cm — (Editorial theory and literary criticism) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 472- 11863- 2 (hardback) — ISBN (invalid) 978- 0- 472- 02892- 4 (e- book) 1. American literature— African American authors— History and criticism— Theory, etc. 2. Criticism, Textual. 3. American literature— African American authors— Publishing— History. 4. Literature publishing— Political aspects— United States— History. 5. African Americans— Intellectual life. 6. African Americans in literature. I. Hutchinson, George, 1953– editor of compilation. II. Young, John K. (John Kevin), 1968– editor of compilation PS153.N5P83 2012 810.9'896073— dc23 2012042607 acknowledgments Publishing Blackness has passed through several potential versions before settling in its current form. -

D' an Examination of 17Th-Century British Burial Landscapes in Eastern

‘Here lieth interr’d’ An examination of 17th-century British burial landscapes in eastern North America by Robyn S. Lacy A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland September 2017 Abstract An archaeological, historical, and geographical survey-based examination, this research focuses on the first organized 17th-century British colonial burial grounds in 43 sites in New England and a further 20 in eastern Newfoundland, and how religious, socio- political, and cultural backgrounds may have influenced the placement of these spaces in relation to their associated settlements. In an attempt to locate the earliest 17th-century burial ground at Ferryland, Newfoundland, this research focuses on statistical analysis, and identifying potential patterns in burial ground placement. The statistical results will serve as a frequency model to suggest common placement and patterns in spatial organization of 17th-century British burial grounds along the eastern seaboard of North America. In addition, text-based and geochemical analyses were conducted on the Ferryland gravestones to aid in determining age and origin. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank everyone who has provided their support and guidance throughout the course of this project. First, I’d like to thank Dr. Barry Gaulton for his endless assistance and support of my ever-growing thesis. I could not have asked for a better supervisor throughout this project, and I hope his future students know how lucky they are. Secondly, I’d like to thank my reviewers, Dr. -

Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court Of

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com AT 15' Fl LEMUEL SHAW I EMUEL SHAW CHIFF jl STIC h OF THE SUPREME Jli>I«'RL <.OlRT OF MAS Wlf .SfcTTb i a 30- 1 {'('• o BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY tHASH BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY 1 9 1 8 LEMUEL SHAW CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT OF MASSACHUSETTS 1830-1860 BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY (Sbe Slibttfibe $rrtf Cambribgc 1918 COPYRIGHT, I9lS, BY FREDERIC HATHAWAY CHASE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Published March iqiS 279304 PREFACE It is doubtful if the country has ever seen a more brilliant group of lawyers than was found in Boston during the first half of the last century. None but a man of grand proportions could have emerged into prominence to stand with them. Webster, Choate, Story, Benjamin R. Curtis, Jeremiah Mason, the Hoars, Dana, Otis, and Caleb Cushing were among them. Of the lives and careers of all of these, full and adequate records have been written. But of him who was first their associate, and later their judge, the greatest legal figure of them all, only meagre accounts survive. It is in the hope of sup plying this deficiency, to some extent, that the following pages are presented. It may be thought that too great space has been given to a description of Shaw's forbears and early surroundings; but it is suggested that much in his character and later life is thus explained. -

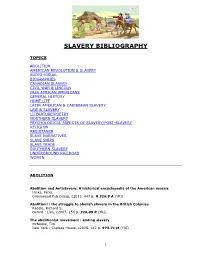

RIVERFRONT CIRCULATING MATERIALS (Can Be Checked Out)

SLAVERY BIBLIOGRAPHY TOPICS ABOLITION AMERICAN REVOLUTION & SLAVERY AUDIO-VISUAL BIOGRAPHIES CANADIAN SLAVERY CIVIL WAR & LINCOLN FREE AFRICAN AMERICANS GENERAL HISTORY HOME LIFE LATIN AMERICAN & CARIBBEAN SLAVERY LAW & SLAVERY LITERATURE/POETRY NORTHERN SLAVERY PSYCHOLOGICAL ASPECTS OF SLAVERY/POST-SLAVERY RELIGION RESISTANCE SLAVE NARRATIVES SLAVE SHIPS SLAVE TRADE SOUTHERN SLAVERY UNDERGROUND RAILROAD WOMEN ABOLITION Abolition and Antislavery: A historical encyclopedia of the American mosaic Hinks, Peter. Greenwood Pub Group, c2015. 447 p. R 326.8 A (YRI) Abolition! : the struggle to abolish slavery in the British Colonies Reddie, Richard S. Oxford : Lion, c2007. 254 p. 326.09 R (YRI) The abolitionist movement : ending slavery McNeese, Tim. New York : Chelsea House, c2008. 142 p. 973.71 M (YRI) 1 The abolitionist legacy: from Reconstruction to the NAACP McPherson, James M. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, c1975. 438 p. 322.44 M (YRI) All on fire : William Lloyd Garrison and the abolition of slavery Mayer, Henry, 1941- New York : St. Martin's Press, c1998. 707 p. B GARRISON (YWI) Amazing Grace: William Wilberforce and the heroic campaign to end slavery Metaxas, Eric New York, NY : Harper, c2007. 281p. B WILBERFORCE (YRI, YWI) American to the backbone : the life of James W.C. Pennington, the fugitive slave who became one of the first black abolitionists Webber, Christopher. New York : Pegasus Books, c2011. 493 p. B PENNINGTON (YRI) The Amistad slave revolt and American abolition. Zeinert, Karen. North Haven, CT : Linnet Books, c1997. 101p. 326.09 Z (YRI, YWI) Angelina Grimke : voice of abolition. Todras, Ellen H., 1947- North Haven, Conn. : Linnet Books, c1999. 178p. YA B GRIMKE (YWI) The antislavery movement Rogers, James T. -

Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents

Between the Covers - Rare Books, Inc. 112 Nicholson Rd (856) 456-8008 will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Discover, and Gloucester City NJ 08030 Fax (856) 456-7675 PayPal. www.betweenthecovers.com [email protected] Domestic orders please include $5.00 postage for the first item, $2.00 for each item thereafter. Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in Overseas orders will be sent airmail at cost (unless other arrange- the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. ments are requested). All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are Members ABAA, ILAB. unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions Cover verse and design by Tom Bloom © 2008 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. Catalogue 143 ~ Holiday 2008 Contents: ................................................................Page Literature (General Fiction & Non-Fiction) ...........................1 Baseball ................................................................................72 African-Americana ...............................................................55 Photography & Illustration ..................................................75 Children’s Books ..................................................................59 Music ...................................................................................80 -

Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783

2014 Felicia Y. Thomas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ENTANGLED WITH THE YOKE OF BONDAGE: BLACK WOMEN IN MASSACHUSETTS, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Deborah Gray White and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Entangled With the Yoke of Bondage: Black Women in Massachusetts, 1700-1783 By FELICIA Y. THOMAS Dissertation Director: Deborah Gray White This dissertation expands our knowledge of four significant dimensions of black women’s experiences in eighteenth century New England: work, relationships, literacy and religion. This study contributes, then, to a deeper understanding of the kinds of work black women performed as well as their value, contributions, and skill as servile laborers; how black women created and maintained human ties within the context of multifaceted oppression, whether they married and had children, or not; how black women acquired the tools of literacy, which provided a basis for engagement with an interracial, international public sphere; and how black women’s access to and appropriation of Christianity bolstered their efforts to resist slavery’s dehumanizing effects. While enslaved females endured a common experience of race oppression with black men, gender oppression with white women, and class oppression with other compulsory workers, black women’s experiences were distinguished by the impact of the triple burden of gender, race, and class. This dissertation, while centered on the experience of black women, considers how their experience converges with and diverges from that of white women, black men, and other servile laborers. -

Remembering Slavery in Massachusetts

Margot Minardi. Making Slavery History: Abolitionism and the Politics of Memory in Massachusetts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. 240 pp. $49.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-537937-2. Reviewed by Jeff Fortney Published on H-CivWar (March, 2012) Commissioned by Hugh F. Dubrulle (Saint Anselm College) According to Margot Minardi in Making Slav‐ Historical narratives written by Jeremy Belk‐ ery History, the history of the American Revolu‐ nap and other early historians in the wake of the tion taught in classrooms for generations, com‐ Revolution emphasized the extent to which aboli‐ plete with a runaway slave as frst martyr and an tionism based on “popular sentiment” ended slav‐ African poet as international celebrity, “owes as ery in Massachusetts--while ignoring the large much to Massachusetts activists and historians in number of “Bay Staters (who) did not share his the nineteenth century as it does to Crispus At‐ [Belknap’s] antislavery views” (p. 20). Further tucks or Phillis Wheatley themselves” (p. 12). Mi‐ complicating this issue were accounts of census nardi embraces the framework of historical mem‐ takers instructed to conduct their counts in such a ory to revisit “the fundamental question of recent way that slaves would not be recorded in the 1790 social history--‘who makes history?’”--including census. Moreover, a law passed in 1788 banning who disappeared, who reappeared, and what this “African or negro” people from living in Massa‐ meant for understanding ideology and identity in chusetts undermined the historical concept of lib‐ Massachusetts (p. 11). Over the course of fve erty for all races espoused in Belknap’s historical chapters, Minardi investigates stories about slaves narrative (p. -

Hjrthe STATE HISTORICAL OCIETY of WISCONSIN

HjrTHE STATE HISTORICAL OCIETY OF WISCONSIN rt-j' lew—*™inTtr ' ' " " tnm in -* -** THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN The STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN is a state-aided corporation whose function is the cultiva- tion and encouragement of the historical interests of the State. To this end it invites your cooperation; member- ship is open to all, whether residents of Wisconsin or elsewhere. The dues of annual members are two dollars, payable in advance; of life members, twenty dollars, payable once only. Subject to certain exceptions, mem- bers receive the publications of the Society, the cost of producing which far exceeds the membership fee. This is rendered possible by reason of the aid accorded the Society by the State. Of the work and ideals of the Society this magazine affords, it is believed, a fair example. With limited means, much has already been accomplished; with ampler funds more might be achieved. So far as is known, not a penny entrusted to the Society has ever been lost or misapplied. Property may be willed to the Society in entire confidence that any trust it assumes will be scrupulously executed. TH *ni ITTTTI mm mri The WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTOEY is published quarterly by the Society, at 450 Ahnaip Street, Menasha, Wisconsin, in September, December, March, and June, and is distributed to its members and exchanges; others who so desire may receive it for the annual subscription of two dollars, payable in advance; single numbers may be had for fifty cents. All correspondence concerning the magazine should be addressed to the office of the State Historical Society, Madison, Wis.