Usefulness of Expected Values in Liability Valuation: the Role of Portfolio Size

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

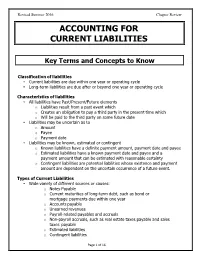

Accounting for Current Liabilities

Revised Summer 2016 Chapter Review ACCOUNTING FOR CURRENT LIABILITIES Key Terms and Concepts to Know Classification of liabilities • Current liabilities are due within one year or operating cycle • Long-term liabilities are due after or beyond one year or operating cycle Characteristics of liabilities • All liabilities have Past/Present/Future elements o Liabilities result from a past event which o Creates an obligation to pay a third party in the present time which o Will be paid to the third party on some future date • Liabilities may be uncertain as to o Amount o Payee o Payment date • Liabilities may be known, estimated or contingent o Known liabilities have a definite payment amount, payment date and payee o Estimated liabilities have a known payment date and payee and a payment amount that can be estimated with reasonable certainty o Contingent liabilities are potential liabilities whose existence and payment amount are dependent on the uncertain occurrence of a future event. Types of Current Liabilities • Wide variety of different sources or causes: o Notes Payable o Current maturities of long-term debt, such as bond or mortgage payments due within one year o Accounts payable o Unearned revenues o Payroll-related payables and accruals o Non-payroll accruals, such as real estate taxes payable and sales taxes payable o Estimated liabilities o Contingent liabilities Page 1 of 16 Revised Summer 2016 Chapter Review Analysis • Liquidity ratios measure short-term ability to pay current liabilities o Current ratio and working capital • Solvency ratios measure the ability to pay short-term and long-term liabilities o Debt to Assets ratio and Times Interest earned ratio Page 2 of 16 Revised Summer 2016 Chapter Review Key Topics to Know Short-Term Notes Payable ** See separate module on Notes Payable ** Current Maturities of Long-Term Debt • The portion of long-term debt payments due within one year. -

Contingencies and Provisions

U.S. GAAP vs. IFRS: Contingencies and provisions Prepared by: Richard Stuart, Partner, National Professional Standards Group, RSM US LLP [email protected], +1 203 905 5027 February 2020 Introduction Currently, more than 120 countries require or permit the use of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), with a significant number of countries requiring IFRS (or some form of IFRS) by public entities (as defined by those specific countries). Of those countries that do not require use of IFRS by public entities, perhaps the most significant is the U.S. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires domestic registrants to apply U.S. generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), while foreign private issuers are allowed to use IFRS as issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (which is the IFRS focused on in this comparison). While the SEC continues to discuss the possibility of allowing domestic registrants to provide supplemental financial information based on IFRS (with a reconciliation to U.S. GAAP), there does not appear to be a specified timeline for moving forward with that possibility. Although the SEC currently has no plans to permit the use of IFRS by domestic registrants, IFRS remains relevant to these entities, as well as private companies in the U.S., given the continued expansion of IFRS use across the globe. For example, many U.S. companies are part of multinational entities for which financial statements are prepared in accordance with IFRS, or may wish to compare themselves to such entities. Alternatively, a U.S. company’s business goals might include international expansion through organic growth or acquisitions. -

Reimagining Accounting to Measure Climate Change Risks

Reimagining Accounting To Measure Climate Change Risks December 4, 2020 PRIMARY CREDIT ANALYST Key Takeaways Imre Guba Madrid - Greater balance-sheet recognition of actual and potential climate-related liabilities +34 91 423 3187 would be a positive step and could be applied under existing accounting standards. This imre.guba @spglobal.com would enable users of financial statements to shift qualitative measures of climate exposures to more quantitative assessments. SECONDARY CONTACT Sam C Holland, FCA - Applying incremental changes to today's accounting practices would contribute not only London to increased transparency around climate-related legal risks, but would also enhance + 44 20 7176 3779 visibility of any capital expenditure (capex) needed to adapt to, or mitigate, future sam.holland climate risks and the potential effects of factors such as consumer preferences and @spglobal.com carbon taxes on demand, revenues, and operating margins. - S&P Global Ratings also supports certain new and more ambitious changes to accounting regimes that would incorporate a wider view of each reporting company's sustainability position. Carbon emissions intensity, and their absolute level, must reduce significantly over the next few decades if the most dramatic climate-change scenarios--and the associated social and economic costs--are to be mitigated. Given this backdrop, it follows that accounting--the means by which companies measure and record financial performance, position, and cash flow generation--needs to be similarly reimagined. Incremental changes can happen alongside the more radical. We believe accounting standards can and should be improved to facilitate the provision of more historic and forward-looking sustainability and climate-related data and information. -

VALUE IFRS Plc Illustrative IFRS Consolidated Financial Statements December 2019

VALUE IFRS Plc Illustrative IFRS consolidated financial statements December 2019 This publication presents the sample annual financial reports of a fictional listed company, VALUE IFRS Plc. It illustrates the financial reporting requirements that would apply to such a company under International Financial Reporting Standards as issued at 31 May 2019. Supporting commentary is also provided. For the purposes of this publication, VALUE IFRS Plc is listed on a fictive Stock Exchange and is the parent entity in a consolidated entity. VALUE IFRS Plc 2019 is for illustrative purposes only and should be used in conjunction with the relevant financial reporting standards and any other reporting pronouncements and legislation applicable in specific jurisdictions. Global Accounting Consulting Services PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP This content is for general information purposes only, and should not be used as a substitute for consultation with professional advisors. About PwC At PwC, our purpose is to build trust in society and solve important problems. We're a network of firms in 158 countries with more than 250,000 people who are committed to delivering quality in assurance, advisory and tax services. Find out more and tell us what matters to you by visiting us at www.pwc.com © 2019 PwC. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the PwC network and/or one or more of its member firms, each of which is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. VALUE IFRS Plc Illustrative IFRS consolidated financial statements December -

Volume VI Chapter 21

Financial Policy Volume VI Liabilities Chapter 21 Contingent Liabilities Approved: _________________________________________ Jon J. Rychalski Assistant Secretary for Management and Chief Financial Officer Department of Veterans Affairs July 2019 Contingent Liabilities Volume VI – Chapter 21 2101 Overview .............................................................................................................. 2 2102 Revisions ............................................................................................................. 2 2103 Definitions ............................................................................................................ 2 2104 Roles and Responsibilities ................................................................................. 4 2105 Policies ................................................................................................................. 4 210501 General Policies ........................................................................................ 4 210502 Estimate of Contingent Liabilities ........................................................... 4 210503 Accounting for Contingent Liabilities ..................................................... 5 210504 Reporting of Contingent Liabilities ......................................................... 6 210505 Unasserted claims and the Legal Representation Letter ...................... 6 2106 Authorities and References .............................................................................. 8 2107 Rescissions ........................................................................................................ -

Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets

FRS-15 Issued 11/00 Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand FINANCIAL REPORTING STANDARD NO. 15 2000 PROVISIONS, CONTINGENT LIABILITIES AND CONTINGENT ASSETS Issued by the Financial Reporting Standards Board Institute of Chartered Accountants of New Zealand Approved November 2000 by the Accounting Standards Review Board Under the Financial Reporting Act 1993 CONTENTS paragraph Introduction ......................................................................................... 1.1 Application .......................................................................................... 2.1 Statement of Purpose .......................................................................... 3.1 Definitions .......................................................................................... 4.1 Financial Reporting Recognition Provisions .............................................................................. 5.1 Present Obligation ........................................................... 5.2 Past Event ......................................................................... 5.4 Probable Outflow of Resources Embodying Economic Benefits ........................................................... 5.10 Reliable Estimate of the Obligation .................................. 5.12 Contingent Liabilities ............................................................. 5.14 Contingent Assets ................................................................... 5.18 Measurement Best Estimate ......................................................................... -

Basic Insurance Accounting—Selected Topics

Basic Insurance Accounting – Selected Topics By Ralph S. Blanchard III, FCAS, MAAA 1 July 2008 CAS Study Note Author’s Change to This Edition This edition of the study note is the same as the June 2007 edition except for the following change to the third paragraph of section 8 on page 23: “Under GAAP all the newly purchased and identified assets and liabilities are to be valued at their “fair value”, with goodwill equal to the difference between the fair value of identified acquired assets and the fair value of identified acquired liabilities” has been changed to “Under GAAP all the newly purchased and identified assets and liabilities are to be valued at their “fair value”, with goodwill equal to the difference between the purchase price and the fair value of identified acquired assets less the fair value of identified acquired liabilities.” Basic Insurance Accounting – Selected Topics The purpose of this study note is to educate actuaries on certain basic insurance accounting topics that may be omitted in other syllabus readings. These topics include: • Loss and loss adjustment expense accounting basics • Reinsurance accounting basics • Examples of how ceded reinsurance impacts an insurers financial statements • Deposit accounting basics In addition, the following two fundamental accounting equations are provided, representing basic equations that may no longer be found in the other syllabus articles but that all actuaries should know. • Assets – Liabilities = Equity (sometimes labeled “net assets” or “surplus”) • Revenue – Expense = Income (with expense including incurred losses and underwriting expenses for an insurance company). (Note: Most accounting systems rely on some form of double-entry bookkeeping, under which all transactions result in debit and credit entries that have to balance. -

Resolving the Tension Between Lawyers and Auditors Over Contingent Liability Disclosure Samantha Nicole Kunz Student of Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2015 From Legally Confidential to Financially Confident: Resolving the Tension between Lawyers and Auditors over Contingent Liability Disclosure Samantha Nicole Kunz Student of Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Kunz, Samantha Nicole, "From Legally Confidential to Financially Confident: Resolving the Tension between Lawyers and Auditors over Contingent Liability Disclosure" (2015). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 1073. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1073 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT MCKENNA COLLEGE From Legally Confidential to Financially Confident: Resolving the Tension between Lawyers and Auditors over Contingent Liability Disclosure SUBMITTED TO Professor James Taylor AND DEAN NICHOLAS WARNER BY Samantha Kunz for SENIOR THESIS Spring 2015 April 27, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincerest gratitude goes out to all of my professors, advisors, mentors, colleagues, friends, and family for their endless support throughout this challenging yet rewarding experience. First, I would like to thank my Business Law professor, Lynne Brickner, for providing me with the inspiration for this topic. Additionally, a big thank you goes to my academic advisor, Professor Marc Massoud, for encouraging me to study this subject in spite of my self-doubt about conducting research in such a specialized field. This thesis would have been significantly less extensive and impactful if it weren’t for the professionals who provided opinions and commentary on my research. I would like to thank John Mackie and John Rubini for sharing their legal expertise with me. -

Cash Flow Statement 6

Cash Flow Statement 6 iill now you have learnt about the financial Tstatements being primarily inclusive of Position Statement (showing the financial position of an enterprise as on a particular date) and Income Statement (showing the result of the operational activities of an enterprise over a particular period). There is also a third important financial statement known as Cash flow statement, which shows inflows and outflows of the cash and cash equivalents. This statement is usually prepared by companies which comes as a tool in the hands of users of financial information to know about the sources and uses of cash and cash equivalents of an enterprise over a period of time from various activities of an enterprise. It has gained substantial importance in LEARNING OBJECTIVES the last decade because of its practical utility to the After studying this chapter, users of financial information. you will be able to : Financial Statement of companies are prepared • state the purpose and preparation of following the accounting standards prescribed in statement of cash flow the companies Act, 2013. Accounting Standards statement; are notified under section 133 of the Companies • distinguish between Act, 2013 vide Accounting Standards Rules, 2006 operating activities, and are mandatory in nature. Companies Act, 2013 investing activities and also specifies that if the accounting standards are financing activities; not followed, financial statements will not be true • prepare the statement and fair, which is a quality of financial statement. of cash flows using Financial Statements are defined in Companies Act, direct method; 2013 (Section 2 (40)] and includes Cash Flow • prepare the cash Statement prepared in accordance with Accounting flow statement using indirect method. -

Accounting for Litigation Contingencies

INSIGHTS VOLUME 31, NUMBER 1, JANUARY 2017 27 SECURITIES LITIGATION Accounting for Litigation Contingencies Certain questions seem to recur when it comes to out- has been incurred, the company must record the side counsel’s communications with a company’s audi- estimated loss or the best estimate from within a tors about potential exposures as a result of litigation, range of losses as a charge to income. If a liability is regulatory, or enforcement matters and the underlying possible or probable, but no reasonable estimation accounting for such matters. First, how can clients satisfy of the loss can be made, the company must disclose auditors’ requests for information without waiving the the nature of the contingency and state that such an attorney-client and work-product privileges? Second, estimate cannot be made. how do the standards for accounting for loss contingen- Although a company often must apply consider- cies apply in circumstances where a company expects able judgment in assessing and estimating contin- insurance to cover any ultimate losses? gent liabilities under ASC 450, these judgments and the facts and circumstances supporting them By Michael Y. Scudder and Andrew J. Fuchs bring careful secondary examination by a company’s independent auditors. A very good example of the Waiving Privilege in Response scrutiny applied to such judgments comes from the to Auditor Requests SEC’s recent enforcement action captioned SEC v. RPM International Inc.1Th e Commission charged an Under the Financial Accounting Standards issuer and its general counsel with violating the secu- Board’s Accounting Standards Codification rities laws for failing to record an accrual or disclose Topic 450 (ASC 450), titled “Contingencies” a loss contingency for a pending DOJ investigation (formerly Financial Accounting Standards No. -

Accounting for Contingencies

A Roadmap to Accounting for Contingencies and Loss Recoveries 2019 The FASB Accounting Standards Codification® material is copyrighted by the Financial Accounting Foundation, 401 Merritt 7, PO Box 5116, Norwalk, CT 06856-5116, and is reproduced with permission. This publication contains general information only and Deloitte is not, by means of this publication, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This publication is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional advisor. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this publication. As used in this document, “Deloitte” means Deloitte & Touche LLP, Deloitte Consulting LLP, Deloitte Tax LLP, and Deloitte Financial Advisory Services LLP, which are separate subsidiaries of Deloitte LLP. Please see www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of our legal structure. Certain services may not be available to attest clients under the rules and regulations of public accounting. Copyright © 2019 Deloitte Development LLC. All rights reserved. Other Publications in Deloitte’s Roadmap Series Business Combinations Business Combinations — SEC Reporting Considerations Carve-Out Transactions Consolidation — Identifying a Controlling Financial Interest Contracts -

Guide to Annual Financial Statements – Illustrative Disclosures 2016

Illustrative disclosures Guide to annual financial statements IFRS® October 2016 kpmg.com/ifrs Contents About this guide 2 Independent auditors’ report 5 Consolidated financial statements 12 Financial highlights 13 Consolidated statement of financial position 14 Consolidated statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 16 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 18 Consolidated statement of cash flows 20 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 22 Appendices I New standards or amendments for 2016 and forthcoming requirements 150 II Presentation of comprehensive income – Two‑statement approach 152 III Statement of cash flows – Direct method 154 IV Example disclosures for entities that early adopt Disclosure Initiative (Amendments to IAS 7) 155 V Example disclosures for entities that early adopt IFRS 9 Financial Instruments (2014) 158 VI Other disclosures not illustrated in the consolidated financial statements 220 Keeping in touch 226 Acknowledgements 228 Notes Basis of preparation 22 Other information 118 1. Reporting entity 22 37. Operating leases 118 2. Basis of accounting 22 38. Commitments 119 3. Functional and presentation currency 22 39. Contingencies 119 4. Use of judgements and estimates 22 40. Related parties 120 41. Subsequent events 123 Performance for the year 24 5. Operating segments 24 Accounting policies 124 6. Discontinued operation 31 42. Basis of measurement 124 7. Revenue 33 43. Correction of errors 125 8. Income and expenses 34 44. Significant accounting policies 126 9. Net finance costs 36 45. Standards issued but not yet effective 142 10. Earnings per share 37 Employee benefits 39 11. Share‑based payment arrangements 39 12. Employee benefits 42 Income taxes 47 13.