Sandia and the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant 1974-1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 30 2018 Seminole Tribune

BC cattle steer into Brooke Simpson relives time Heritage’s Stubbs sisters the past on “The Voice” win state title COMMUNITY v 7A Arts & Entertainment v 4B SPORTS v 1C Volume XLII • Number 3 March 30, 2018 National Folk Museum 7,000-year-old of Korea researches burial site found Seminole dolls in Manasota Key BY LI COHEN Duggins said. Copy Editor Paul Backhouse, director of the Ah-Tah- Thi-Ki Museum, found out about the site about six months ago. He said that nobody BY LI COHEN About two years ago, a diver looking for Copy Editor expected such historical artifacts to turn up in shark teeth bit off a little more than he could the Gulf of Mexico and he, along with many chew in Manasota Key. About a quarter-mile others, were surprised by the discovery. HOLLYWOOD — An honored Native off the key, local diver Joshua Frank found a “We have not had a situation where American tradition is moving beyond the human jaw. there’s organic material present in underwater horizon of the U.S. On March 14, a team of After eventually realizing that he had context in the Gulf of Mexico,” Backhouse researchers from the National Folk Museum a skeletal centerpiece sitting on his kitchen said. “Having 7,000-year-old organic material of Korea visited the Hollywood Reservation table, Frank notified the Florida Bureau of surviving in salt water is very surprising and to learn about the history and culture Archaeological Research. From analyzing that surprise turned to concern because our surrounding Seminole dolls. -

Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace In

TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: History TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terry H. Anderson Committee Members, Jon R. Bond H. W. Brands John H. Lenihan David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace in Korea. (May 2008) Larry Wayne Blomstedt, B.S., Texas State University; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terry H. Anderson This dissertation analyzes the roles of the Harry Truman administration and Congress in directing American policy regarding the Korean conflict. Using evidence from primary sources such as Truman’s presidential papers, communications of White House staffers, and correspondence from State Department operatives and key congressional figures, this study suggests that the legislative branch had an important role in Korean policy. Congress sometimes affected the war by what it did and, at other times, by what it did not do. Several themes are addressed in this project. One is how Truman and the congressional Democrats failed each other during the war. The president did not dedicate adequate attention to congressional relations early in his term, and was slow to react to charges of corruption within his administration, weakening his party politically. -

June 1-15, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/2/1972 A Appendix “B” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/5/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/6/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/9/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/12/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1972 – June 15, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THF WHITE ,'OUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Travel Record for Travel AnivilY) f PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day. Yr.) _u.p.-1:N_E I, 1972 WILANOW PALACE TIME DAY WARSAW, POLi\ND 7;28 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ccd R=Received ACTIVITY 1----.,------ ----,----j In Out 1.0 to 7:28 P The President requested that his Personal Physician, Dr. -

The Atomic Energy Commission

The Atomic Energy Commission By Alice Buck July 1983 U.S. Department of Energy Office of Management Office of the Executive Secretariat Office of History and Heritage Resources Introduction Almost a year after World War II ended, Congress established the United States Atomic Energy Commission to foster and control the peacetime development of atomic science and technology. Reflecting America's postwar optimism, Congress declared that atomic energy should be employed not only in the Nation's defense, but also to promote world peace, improve the public welfare, and strengthen free competition in private enterprise. After long months of intensive debate among politicians, military planners and atomic scientists, President Harry S. Truman confirmed the civilian control of atomic energy by signing the Atomic Energy Act on August 1, 1946.(1) The provisions of the new Act bore the imprint of the American plan for international control presented to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission two months earlier by U.S. Representative Bernard Baruch. Although the Baruch proposal for a multinational corporation to develop the peaceful uses of atomic energy failed to win the necessary Soviet support, the concept of combining development, production, and control in one agency found acceptance in the domestic legislation creating the United States Atomic Energy Commission.(2) Congress gave the new civilian Commission extraordinary power and independence to carry out its awesome responsibilities. Five Commissioners appointed by the President would exercise authority for the operation of the Commission, while a general manager, also appointed by the President, would serve as chief executive officer. To provide the Commission exceptional freedom in hiring scientists and professionals, Commission employees would be exempt from the Civil Service system. -

Dixy Lee Ray, Marine Biology, and the Public Understanding of Science in the United States (1930-1970)

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Erik Ellis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the History of Science presented on November 21. 2005. Title: Dixy Lee Ray. Marine Biology, and the Public Understanding of Science in the United States (1930-1970) Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy This dissertation focuses on the life of Dixy Lee Ray as it examines important developments in marine biology and biological oceanography during the mid twentieth century. In addition, Ray's key involvement in the public understanding of science movement of the l950s and 1960s provides a larger social and cultural context for studying and analyzing scientists' motivations during the period of the early Cold War in the United States. The dissertation is informed throughout by the notion that science is a deeply embedded aspect of Western culture. To understand American science and society in the mid twentieth century it is instructive, then, to analyze individuals who were seen as influential and who reflected widely held cultural values at that time. Dixy Lee Ray was one of those individuals. Yet, instead of remaining a prominent and enduring figure in American history, she has disappeared rapidly from historical memory, and especially from the history of science. It is this very characteristic of reflecting her time, rather than possessing a timeless appeal, that makes Ray an effective historical guide into the recent past. Her career brings into focus some of the significant ways in which American science and society shifted over the course of the Cold War. Beginning with Ray's early life in West Coast society of the1920sandl930s, this study traces Ray's formal education, her entry into the professional ranks of marine biology and the crucial role she played in broadening the scope of biological oceanography in the early1960s.The dissertation then analyzes Ray's efforts in public science education, through educational television, at the science and technology themed Seattle World's Fair, and finally in her leadership of the Pacific Science Center. -

Dr. Earl Davis Is Always Busy with University of Texas at Austin and Completed His One Task Or Another

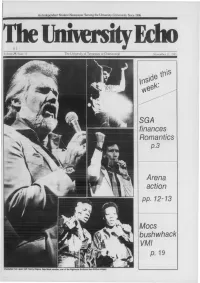

An Independent Student Newspaper Serving the University Community Since 1906 The University Echo <?3 • .-. W Volume/?f?/Issue The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga November II, 1983 SGA finances Romantics p.3 Arena action pp. 12-13 Mocs bushwhack VMI p. 19 Clockwise Irom upper left: Kenny Rogers, Gap Band member, one of the Righteous Brothers, New Edition singers. "Our Personnel Touch guarantees you quality service. Thanks tn Pi tWa Phi f„r rhi, pi.-t..,-,- I'II niri-fl ni-n rimis-.Li ^^'inrlniH Echo News 2 The Echo/November 11, 1983 No pay raise this year UTC faculty salaries below average By Sandy Fye Echo News Editor UTC will need $903,600 to bring faculty salaries up 155 and over stay, then there's no room for new faculty. to Southern Region Education Board (SREB) And we can't afford to retire. averages, according to information compiled by Dave To reach 1982-1983 fiscal year faculty pay "On the whole, I think we've got the best teaching Larson, vice chancellor of administration and finance, averages: faculty in the state," continued Printz. "But it makes in his "Planning for Excellence" report. 66 professors need an average of $2755 each you sort of sad that you can't afford to send your Because report figures were based on 1982-83 109 associate professors need an average of children somewhere else, so they won't be burdened SREB averages, much more money will be necessary $2330 each by having a parent on campus." to raise the salary level to the current average as the 85 assistant professors need an average of $2798 Printz said many former UTC faculty and staff UTC faculty did not receive pay raises for 1983 84, for each members have relocated to other jobs or out of the cost-of-living or otherwise. -

Charles Z. Smith Papers File://///Files/Shareddocs/Librarycollections/Manuscriptsarchives/Findaidsi

Charles Z. Smith papers file://///files/shareddocs/librarycollections/manuscriptsarchives/findaidsi... UNIVERSITY UBRARIES w UNIVERSITY of WASH INCTON Spe, ial Colle tions. Charles Z. Smith papers Inventory Accession No: 3306-001 Special Collections Division University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, Washington, 98195-2900 USA (206) 543-1929 This document forms part of the Guide to the Charles Z. Smith Papers. To find out more about the history, context, arrangement, availability and restrictions on this collection, click on the following link: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/permalink/SmithCharlesZUA3306/ Special Collections home page: http://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/ Search Collection Guides: http://digital.lib.washington.edu/findingaids/search 1 of 1 8/19/2015 6:33 PM CHARLES Z. SMITH Accession No. 3306-83-5 INVENTORY Box Seri es Folders Dates BIOGRAPH I CAL FEATURES GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE A - Z 5 1973-80 Unsorted Correspondence l 966-79 American Jewish Committee 1974 American Judicature Society 1973-74 Atlantic Richfield Company 1977 First Baptist Church 1976-81 National College of Criminal Defense Lawyers and Public Defenders 1973-75 National College of the State Judiciary 1975-76 Seattle (correspondence with various offices) 1974-78 Seattle. Pol ice Department 1971-80 Seattle . Schools 1974-80 Seattle-King County Public Defender 1972-79 United States (correspondence with various governmental departments) 1974 U. S. Defense Department. Military Appeals Court 1979 U.S. Health, Education and Welfare Department 1974-79 University of Puget Sound. Law School 1973-77 Washington (correspondence with various governmental departments) 1974-78 Washington. Governor (Daniel J. Evans) 1966-76 Washington . Governor (Dixy Lee Ray) 1976-80 Washington. -

Tragedy Strik, Es Town Manager

· Vol. 79 No. 11 Bulk Rate,U-8 P~~taoe PaTf1 TUESDAY, OCTOBER 1 t, 1988 (603)862-1490 Durham.N.H. Durham 1\1 H Perm,, ,r3(i Tragedy Strik,es ·Plea to picket town manager decision process By Pamela DeKoning "If we could go back to the Students were called on to poinL where students were By R. Scott Nelson search will be expanded today picket the process usea by the . involved and come up with the st The search continues for from Nubble Light seven miles admini ration to determine its same conclusions about a site, , I Durham Town Administrator -. south to Ogunquit, with a final new housing site at an emotion- . I,would be happy. The point. is ~ Terry.Hundley and his _11-year · search o-f the accident scene to al forum in Hamiltion Smith that students and faculty were old daughter who were lost and · be conducted at 4 p.m.. last night. , not consulted," he said. presumed drowned Sunday after ,'The s.earch was expanded Jennifer Rand, organizer of Condon also expressed con- · being swept into the ocean near because of extra people, We got the equine students who oppose cerns over the contracting firm Maine.' a whole bunch of help from the administration's , plans, Aring Schroeder which has been Xhe pair was on a large rock vohmteers," Finley said. asked s_tudents to picket Friday's the consultant in architectural below Bald Head Cliff watching "We won'.t allow the search rededication of the·New Eng- matters. Felix De Vito, the swells created by an offshore to be conducted Tuesday if it'.s land Center at 3:30 p.m., when former Campus Planner for the storm when a large wav~ pulled raining and wet," Finley added. -

October 11, 1992 MEMORANDUM to the LEADER FROM: JOHN

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu October 11, 1992 MEMORANDUM TO THE LEADER FROM: JOHN DIAMANTAKIOU SUBJECT: POLITICAL BRIEFINGS Below is an outline of your briefing materials for your appearances throughout the month of October. Enclosed for your perusal are: 1. Campaign briefing: • overview of race • biographical materials • Bills introduced in 102nd Congress 2. National Republican Senatorial Briefing 3. City Stop/District race overview 4. Governor's race brief (WA, UT, MO) 5. Redistricting map/Congressional representation 6. NAFTA Brief 7. Republican National Committee Briefing 8. State Statistical Summary 9. State Committee/DFP supporter contact list 10 Clips (courtesy of the campaigns) 11. Political Media Recommendations (Clarkson/Walt have copy) Thank you. Page 1 of 72 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas 10-08-1992 08=49RM FROM CHANDLER 92http://dolearchives.ku.edu TO 12022243163 P.02 CHANDLER-~2 MEMORANDUM TO: John Diamantakiou FR: Kraig Naasz RE: Senator Dole's Visit DT: October 7, 1992 I On Rod's be9Flf, I want to thank you for all your help. I hope the followinj information and attachments are of assistance to you and Senator Doi 11e. · I 1!,! I Primary Election In Washington's open primary, Rod finished first ahead of Leo Thorsness and Tim Hill with 21% of the vote. Patty Murray, who had only one Democrat foe, finished with 29% of the vote. No independent candidate qualified for the general election ballot. A total of 541, 267 votes were cast for one of the three Republicans in the primary (48.6% of the vote). -

"Notice of Appearance for Applicant" and "Answer of Applicant." These Should Also Be on File in the Public Document Room in Scottsboro

41 .40 August 30, 1973 William E. Garner, Esq. Route 4, Box 354 Scottsboro, Alabama 35768 In the Matter of Tennessee Valley Authority Bellefonte Nuclear Plant, Units 1 and 2 Docket Nos. 50-438 and 50-439 Dear Bill, In response to your request, I attach a copy of the "Notice of Appearance for Applicant" and "Answer of Applicant." These should also be on file in the Public Document Room in Scottsboro. Enclosed are the biographies you requested. Very truly yours, William D. Paton Counsel for AEC Regulatry Staff Enclosures: Distribution: OGC files 1. Notice of Appearance for Applicant Germantown 2. Answer of Applicant Reg Central files 3. Biography of Elizabeth S. Bowers, Shapar/Engblhardt PDR Scinto/Karman Chairman of Atomic Safety and LPDR DL - D. Davis Licensing Board, and other ASLAB EP - G. Dittman biographies as requested ASLBP Formal files Chron WDPaton C13 WDPJ A~b~ 9 I DAj E .... /3 0 / 73 ----- -- ----------I---- --------- --------------- -------- Form AEC-318 (Rev. 9-53) AECM 0240 GPO c43-16-81465-1 445-678 to ct. UNITED STATES ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20545 FES August 30, 1973 William E. Garner, Esq. * Route 4, Box 354 Scottsboro, Alabama 35768 In the Matter of Tennessee Valley Authority Bellefonte Nuclear Plant, Units 1 and 2 Docket Nos. 50-438 and 50-439 Dear Bill, In response to your request, I attach a copy of the "Notice of Appearance for Applicant" and "Answer of Applicant." These should also be on file in the Public Document Room in Scottsboro. Enclosed are the biographies you requested. Very truly yours, William D. -

Thomas Kuchel Oral History Interview I

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION The LBJ Library Oral History Collection is composed primarily of interviews conducted for the Library by the University of Texas Oral History Project and the LBJ Library Oral History Project. In addition, some interviews were done for the Library under the auspices of the National Archives and the White House during the Johnson administration. Some of the Library's many oral history transcripts are available on the INTERNET. Individuals whose interviews appear on the INTERNET may have other interviews available on paper at the LBJ Library. Transcripts of oral history interviews may be consulted at the Library or lending copies may be borrowed by writing to the Interlibrary Loan Archivist, LBJ Library, 2313 Red River Street, Austin, Texas, 78705. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION LYNDON BALNES JOHNSON LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interview of THOMAS H. KUCHEL In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code, and subject to the terms and conditions hereinafter set forth, I, Betty M. Kuchel, of Los Angeles, California, do hereby give, donate and convey to the United States of America all my rights, title, and interest in the transcript and the tape recording of the personal interview conducted with my late husband, Thomas H. Kuchel, on May 15, 1980 at Los Angeles, California, and prepared for deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. This assignment is subject to the following terms and conditions: (1) The transcript shall be available for use by researchers as soon as it has been deposited in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. -

The Department of Agriculture: a Historical Note

The Department of Agriculture: A Historical Note The U.S. Department of Agriculture was established on May 15, 1862, by a law signed by President Abraham Lincoln. The new Department was "to acquire and to diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected with agriculture in the most general and comprehensive sense of the word." In carrying out his duties, the Commissioner was authorized to conduct experiments, collect statistics, and to collect, test, and distribute new seeds and plants. This law, very broad in scope, has remained the basic authority for the Department to the present time. Proposals for an agricultural branch of the national government had been made as early as 1776. George Washington recommended the establishment of such an agency in 1796. The Secretary of the Treasury gave the idea support in 1819 by asking consuls and naval officers abroad to send home seeds and improved breeds of domestic animals. In 1836, Henry L. Ellsworth, Commissioner of Patents, on his own initiative undertook to distribute seeds obtained from abroad to enterprising farmers. Three years later Congress appropriated $1,000 of Patent Office fees for collecting agricultural statistics, conducting agricultural investigations, and distributing seeds. By 1854, the Agricultural Division of the Patent Office employed a chemist, a botanist, and an entomologist, and was conducting experiments, During this period many farm editors, agricultural leaders, and officers of the numerous county and state agricultural societies continued to urge that agriculture be represented by a separate agency. The United States Agricultural Society assumed leadership of the movement, and its efforts, combined with the pledges of thé Republican Party in 1860 for agrarian reforms that would encourage family farms, led to the establishment of the Department.