DMCA Exemption Comment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) ‘Whose Vietnam?’ - ‘Lessons learned’ and the dynamics of memory in American foreign policy after the Vietnam War Beukenhorst, H.B. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Beukenhorst, H. B. (2012). ‘Whose Vietnam?’ - ‘Lessons learned’ and the dynamics of memory in American foreign policy after the Vietnam War. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 Bibliography Primary sources cited (Archival material, government publications, reports, surveys, etc.) ___________________________________________________________ Ronald Reagan Presidential Library (RRPL), Simi Valley, California NSC 1, February 6, 1981: Executive Secretariat, NSC: folder NSC 1, NSC Meeting Files, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library (RRPL). ‘News clippings’, Folder: ‘Central American Speech April 27, 1983 – May 21, 1983’, Box 2: Central American Speech – Exercise reports, Clark, William P.: Files, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library (RRPL). -

Vita PDF Download

AMOR SCHUMACHER SYNCHRON (Rollen und Ensemble) Auswahl „The Dinner“ Splendid Nana Spier „Superstore“ BSG Frank Muth „Librarians“ Interopa Elke Weidemann „Billions“ Cinephon Reinhard Knapp „Patriots Day“ RC Bernhard Völger „Collateral Beauty“ FFS Marianne Gross „Christmas Office RC Kathrin Fröhlich Party“ „La La Land“ Cinephon Dr. Harald Wolff „House of Lies“ Cinephon Dr. Harald Wolff Wohnort: Berlin „Flikken Maastricht“ Antares Marc Böttcher Geburtsdatum: 14.08.1979 Sprachen: deutsch (Muttersprache), „Paradise“ Studio Funk Olaf Mierau spanisch (Muttersprache), „Homeland“ Cinephon Stephan Hoffmann englisch (fliessend), italienisch (GK) „Istanbul“ Taunusfilm Beate Klöckner Dialekte: hessisch, American English, „Better Call Saul“ BSG Frank Muth British English „Brigade“ SDI Uschi Hugo Akzente: englisch, spanisch, französisch, italienisch, arabisch „Bull“ Cinephon Stefan Ludwig Stimmlage: Alt „New Girl“ Cinephon Martin Schmitz „Bad Batch“ SDI Bernhard Völger Sprachberatung: Spanisch diverse Dialekte „Die irre Heldentour Interopa Christoph Cierpka des Billy Lynn“ „The Strain“ Cinephon Stefan Ludwig „Brotherhood“ Cinephon Wolfgang Ziffer AUSBILDUNG „Veep“ Cinephon Stefan Ludwig „Captain America: FFS Björn Schalla 2009, 2010, 2012 Larry Moss, Susan Civil War“ Batson Masterclass, „I Zombie“ Arena Synchron Gabrielle Pietermann Meisner Technique Mike Bernardin, Berlin „Relentless Justice“ Lautfabrik U.G. Benjamin Plath 2002 - 2006 Berliner Schule für „Longmire” FFS Marianne Gross Schauspiel „ScoobyDoo” SDI Sven Plate 2000 Method Studio London „Vampire -

Paul Hightower Instrumentation Technology Systems Northridge, CA 91324 [email protected]

COMPRESSION, WHY, WHAT AND COMPROMISES Authors Hightower, Paul Publisher International Foundation for Telemetering Journal International Telemetering Conference Proceedings Rights Copyright © held by the author; distribution rights International Foundation for Telemetering Download date 06/10/2021 11:41:22 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631710 COMPRESSION, WHY, WHAT AND COMPROMISES Paul Hightower Instrumentation Technology Systems Northridge, CA 91324 [email protected] ABSTRACT Each 1080 video frame requires 6.2 MB of storage; archiving a one minute clip requires 22GB. Playing a 1080p/60 video requires sustained rates of 400 MB/S. These storage and transport parameters pose major technical and cost hurdles. Even the latest technologies would only support one channel of such video. Content creators needed a solution to these road blocks to enable them to deliver video to viewers and monetize efforts. Over the past 30 years a pyramid of techniques have been developed to provide ever increasing compression efficiency. These techniques make it possible to deliver movies on Blu-ray disks, over Wi-Fi and Ethernet. However, there are tradeoffs. Compression introduces latency, image errors and resolution loss. The exact effect may be different from image to image. BER may result the total loss of strings of frames. We will explore these effects and how they impact test quality and reduce the benefits that HD cameras/lenses bring telemetry. INTRODUCTION Over the past 15 years we have all become accustomed to having television, computers and other video streaming devices show us video in high definition. It has become so commonplace that our community nearly insists that it be brought to the telemetry and test community so that better imagery can be used to better observe and model systems behaviors. -

Thi Bui's the Best We Could Do: a Teaching Guide

Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do: A Teaching Guide The UO Common Reading Program, organized by the Division of Undergraduate Studies, builds community, enriches curriculum, and engages research through the shared reading of an important book. About the 2018-2019 Book A bestselling National Book Critics Circle Finalist, Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do offers an evocative memoir about the search for a better future by seeking to understand the past. The book is a marvelous visual narrative that documents the story of the Bui family escape after the fall of South Vietnam in the 1970s, and the difficulties they faced building new lives for themselves as refugees in America. Both personal and universal, the book explores questions of community and family, home and healing, identity and heritage through themes ranging from the refugee experience to parenting and generational changes. About the Author Thi Bui is an author, illustrator, artist, and educator. Bui was born in Vietnam three months before the end of the Vietnam War and came to the United States in 1978 as part of a wave of refugees from Southeast Asia. Bui taught high school in New York City and was a founding teacher of Oakland International High School, the first public high school in California for recent immigrants and English learners. She has taught in the MFA in Comics program at California College for the Arts since 2015. The Best We Could Do (Abrams ComicArts, 2017) is her debut graphic novel. She is currently researching a work of graphic nonfiction about climate change in Vietnam. -

Image Resolution

Image resolution When printing photographs and similar types of image, the size of the file will determine how large the picture can be printed whilst maintaining acceptable quality. This document provides a guide which should help you to judge whether a particular image will reproduce well at the size you want. What is resolution? A digital photograph is made up of a number of discrete picture elements, known as “pixels”. We can see these elements if we magnify an image on the screen (see right). Because the number of pixels in the image is fixed, the bigger we print the image, then the bigger the pixels will be. If we print the image too big, then the pixels will be visible to the naked eye and the image will appear to be poor quality. Let’s take as an example an image from a “5 megapixel” digital camera. Typically this camera at its maximum quality setting will produce images which are 2592 x 1944 pixels. (If we multiply these two figures, we get 5,038,848 pixels, which approximately equates to 5 million pixels/5 megapixels.) Printing this image at various sizes, we can calculate the number of pixels per inch, more commonly referred to as dots per inch (dpi). Just note that this measure is dependent on the image being printed, it is unrelated to the resolution of the printer, which is also expressed in dpi. Original image size 2592 x 1944 pixels Small format (up to A3) When printing images onto A4 or A3 pages, aim for 300dpi if at all Print size (inches) 8 x 6 16 x 12 24 x 16 32 x 24 possible. -

Julia Reichert and the Work of Telling Working-Class Stories

FEATURES JULIA REICHERT AND THE WORK OF TELLING WORKING-CLASS STORIES Patricia Aufderheide It was the Year of Julia: in 2019 documentarian Julia Reichert received lifetime-achievement awards at the Full Frame and HotDocs festivals, was given the inaugural “Empowering Truth” award from Kartemquin Films, and saw a retrospec- tive of her work presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (The International Documentary Association had already given her its 2018 award.) Meanwhile, her newest work, American Factory (2019)—made, as have been all her films in the last two decades, with Steven Bognar—is being championed for an Academy Award nomination, which would be Reichert’s fourth, and has been picked up by the Obamas’ new Higher Ground company. A lifelong socialist- feminist and self-styled “humanist Marxist” who pioneered independent social-issue films featuring women, Reichert was also in 2019 finishing another film, tentatively titled 9to5: The Story of a Movement, about the history of the movement for working women’srights. Yet Julia Reichert is an underrecognized figure in the contemporary documentary landscape. All of Reichert’s films are rooted in Dayton, Ohio. Though periodically rec- ognized by the bicoastal documentary film world, she has never been a part of it, much like her Chicago-based fellow Julia Reichert in 2019. Photo by Eryn Montgomery midwesterners: Kartemquin Films (Gordon Quinn, Steve James, Maria Finitzo, Bill Siegel, and others) and Yvonne 2 The Documentary Film Book. She is absent entirely from Welbon. 3 Gary Crowdus’s A Political Companion to American Film. Nor has her work been a focus of very much documentary While her earliest films are mentioned in many texts as scholarship. -

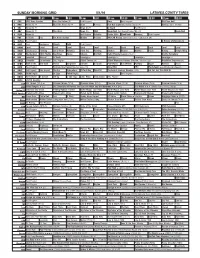

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Paratracks in the Digital Age: Bonus Material As Bogus Material in Blood Simple (Joel and Ethan

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. Werner Huber, Evelyne Keitel, Gunter SO~ (eds.) - I lntermedialities ~ Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier Aeier Feb. Paratracks in the Digital Age: Bonus Material as Bogus Material in Blood Simple (Joel and Ethan 919. Coen, 1984/2001) Eckart Voigts-Virchow Introducing the Paratrack: The DVD Audio Commentary ' In the past few years, the DVD has wreaked havoc in the cinema. Just like the video cassette and the laser disc, it serves the movie industry as an ancillary market for theatrical releases - but worries about illegal copying abound. Consumers are as likely to encounter movies in the cinema and on television as in the comfort of their home on Digital Versatile Disk (DVD), which has virtually replaced the VCR tape. The ris zu appearance of the DVD has re-structured the apparatus of film/video and has gene 160- rated an increasing number of varied paratextual traces that bring film closer to Gerard Genette's model of the paratext - the printed codex or book. The practice of attaching audio commentaries to movies had already begun with the laser disc. -

Title: Title: Title

Title: Academy, The in - Best Short Plays of the World Theatre: 1958-1967 / COL Author: Fratti, Mario Rosenthal, Raymond Publisher: Crown Publishers 1968 Description: roy comedy - satire - women eight characters seven male; one female one act 1 interior set. "A Venetian professor believing Fascist Italy was unjustly defeated by the Americans has thought up an unusual revenge. He organizes a school for gigolos catering to American female tourists". Title: Academy, The in - Mario Fratti's The Cage, The Academy and The Refrigerators / COL Author: Fratti, Mario Publisher: Samuel French 1970 Description: roy comedy - satire - women eight characters seven male; one female one act 1 interior set. "A Venetian professor believing Fascist Italy was unjustly defeated by the Americans has thought up an unusual revenge. He organizes a school for gigolos catering to American female tourists". Title: Actuality of Henrik, The in - Dramatics (October 2013) / PER Author: Sellers, Jacob Publisher: Miscellaneous 2013 Description: roy comedy - absurdist seven characters; extras (doubling possible) flexible casting one act presented in a staged reading as part of the Thespian Playworks program at the 2013 Thespian Festival. George wakes up in a room full of people he doesn't know. Not knowing whether he is dreaming or awake, what ensues is an absurd, wacky comedy all about finding the truth and whether or not finding out the truth will actually make us happy. Title: Admirable Bashville; or, Constancy Unrewarded, The in - Seven One Act Plays / COL Author: Shaw, George Bernard Publisher: Penguin Books 1958 Description: roy comedy - farce - romance nine characters; extras seven male; two female three scenes 3 interiors; 1 exterior. -

The Daily Egyptian, April 28, 1978

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC April 1978 Daily Egyptian 1978 4-28-1978 The aiD ly Egyptian, April 28, 1978 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_April1978 Volume 59, Issue 144 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, April 28, 1978." (Apr 1978). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1978 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in April 1978 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ByJ~... Neu After the romplaints are submitted to Board chairman I Is a law studMlt and SCaUWriter Brian Adams. the I"I«tion official. he his finals start next wm. That makt'S It ~ contested Studftd GOV«lIment IillBt rule 011 them. Beller said that ie kind of hard." election results may be brought to • certifying the vote tallies. Adams If. order to have a fwoarinj{. 5e'Vm J hearing .. early as Friday. Robert .utomatically rule1l the complaints ~d. mt'Tllbm5 must bt- prt"it'nt. A J.Board may hear Beller. chairman 01 the Judicial Board, ....alid. maJOl1ty of four Yotes is ~ to ap said Thursday. "Thea he (AJexander) can appeal to prove a rulHlff election. an option Beller Minutes after the unofficial result. 1M J.Board.·' Beller said. He said SOI11e admits is possible. election charges were tabulated WedMsday night. ~ .... students also romplained Wed •• Anything is possible," Beller said. "If were challenged by ~ Alexander, nesday that the Health Service poll WB'I the board votes far another electim. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations.