Morris Birkbeck's Estimate of the People of Princeton in 1817

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Craig R. Ehlen 10929 Driver Drive Evansville, Indiana 47725

Craig R. Ehlen 10929 Driver Drive Evansville, Indiana 47725 812/867-6164 (Home) 812/464-1785 (Office) 812/465-1044 (Fax) [email protected] Education: Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) — Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (1994) Dissertation title: “An empirical examination of the fairness of AICPA- mandated peer and quality review decision-making procedures and their effects on reviewees’ attitudes toward the AICPA and the reviewer” Master of Accounting Science (MAS) — University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (1969) Bachelor of Science in Accountancy (BS) — University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (1968) Professional Certifications: Chartered Global Management Accountant — Indiana (2012) Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE) — Indiana (1997) Certified Public Accountant (CPA) — Illinois (1968) Affiliations: American Accounting Association American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Indiana CPA Society University of Illinois Alumni Association Major Awards and Honors: Indiana CPA Society “Outstanding Educator” Award (2001) USI College of Business “Excellence in Research” Award (2006, 2003, and 1999) USI College of Business Student Learning and Teaching Innovation Fellowship (2006) USI College of Business R. Malcolm Koch Research Fellowship (1998) Indiana CPA Educational Foundation Doctoral Loan/Grant (1994/1995) AICPA Doctoral Fellow (1991/1992 and 1990/1991) Bronze Tablet Scholar — University of Illinois (1968) 1 Teaching Experience: 2002 — present: Professor of Accounting Department -

History of Warrick and Its Prominent People : from the Earliest Time to The

Class _L5J3l2^^ Copyright N^ COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT. HISTORY i>T O F W A R R I C K AND ITS PROMINENT PEOPLE From the Earliest Time to the Present; Together with Interesting- Biographical Sketches, Reminiscences, Notes, Etc. '^Uvo-v-. LLUSTRATED NINETEEN HUNDRED AND NINE CRESCENT PUBLICATION COMPANY '^9 1 B o o n \ i 1 e , Indiana b V \H^ ^ TO T TI A T () X E Whose encouragenienl aiul aid resulted in this work THIS V O L U iM E is (iratefullv Dech'iated. LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two COBies Received MAY 17 1909 Copyriunt tntry g COPYRIGHT 1909 NO CLASS A[ ^ XXc. BY MONTE M. KATTERJOHf PREFACE. Tliis volume is doubtless one with many faults, for no history extant is free from errors. Great care was taken in preparing the matter found herein, and all discrepancies were eradicated. I n- just criticism cannot rectify the errors that are sure to apjiear, and the author feels assured that all thoughtful jjeople will recognize and a])preciate the undertaking, also realize that a i)ublic benefit has been accomplished. The biographical sectioii is devoted to the record of men, living and dead. If it is incomplete, the fault cannot be justly attributed to the author. Many people were solicited, but on mone- tary grounds refused to support the publication. Those who read this book, and who know what constitutes a true history, will agree with the author that this volume is sujierior to any ever published in this county, inasmuch as its fine illustra- tions are a single history within themselves. -

History of the English Settlement in Edwards County, Illinois : Founded

L I B RA R,Y OF THE U N I VER.5 ITY or ILLI NOIS 57737.31 F66h f RHHSIS BSIsJiM aiiffiE? 1 i I, I (I I 1 I 'i (Chicago ]^iBtoxica( ^ocieig COLLECTION Vol. I. Tke Libria of the Uiitv«r«ity of Illinois -^•^/^^r <y y^ ^^. i. a^^ rhotti-Mcchauiciil Printinjj; Co., Chicaj^o. Tk« Ubfiry of the 4n Chicago Historical Society's Collection. —Vol. I. HISTORY OF THE Englisli Settlement in Edwards County ILLINOIS, Founded in 1817 and 18 18, by MORRIS BIRKBECK A\'D GEORGE FLOWER. BY GEORGE FLOWER. WITH PREFACE AND FOOT-NOTES BY E. B. WASH BURN E, Member of the Chicago Historical Society; Honorary Member of the Massa- chusetts AND Virginia Historical Societies; Corresponding Member of the Maine Historical Society; author of the "Sketch of Edward Coles, and the Slavery Struggle in Illinois in 1823-4." etc., etc. CHICAGO: FERGUS PRINTING COMPANY. 1882. 977.3791 CONTENTS. Introductory, Preface, CHAPTER I. Prefatory Remarks The Founders of the Enghsh Colony in Illinois, Morris Birkbeck and George Flower Sketch of Morris Birkbeck —His Father a Quaker His Education and Early Life in Eng- land— Travels of Birkbeck and Flower through France -Edward Coles visits Mr. Birkbeck and Family at Wanborough, England — Coles afterward becomes Governor of Illinois, and Birkbeck his Secretary-of-State Characteristics of Birkbeck Embarks for the United States in April, 1817 — Richard Flower, father of George Flower Reflections on the United States —George Flower in the United States a year before Birkbeck. - - 17 CHAPTE R II. Mr. Flower sails for America — Reflections on the Voyage—Arrives in New York and visits Philadelphia— Invited to Monticello by Mr. -

American Identity in the Illinois Territory, 1809-1818 Daniel Northrup Finucane

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research Spring 2003 American identity in the Illinois Territory, 1809-1818 Daniel Northrup Finucane Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Recommended Citation Finucane, Daniel Northrup, "American identity in the Illinois Territory, 1809-1818" (2003). Honors Theses. Paper 317. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN IDENTITY IN THE ILLINOIS TERRITORY, 1809-1818 by Daniel Northrup Finucane Honors Thesis m Department of History University of Richmond Richmond, Virginia April 25, 2003 Advisors: Hugh West and Matt Basso Acknowled!!ments I would like to thank several people without whom my thesis would not have been possible. Professor Hugh West offered his guidance on this project not only for me, but for the other three who researched and wrote an honors thesis. His checkpoints and deadlines throughout the year helped curb my procrastination, and his criticism was timely, accurate, and extremely helpful. Professor Matt Basso, a scholar of the American West at the University, also aided my progress - pointing me in the right direction at the beginning of my research. He reeled off the names of numerous books necessary to my study and worked with me to develop a provocative argument. I would like to thank the Jim Gwin, the Collection Librarian at the University's Boatwright Memorial Library, for offering his services to the project. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46106 73-26,887

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings of^pitterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Gibson County LRTP

LONG RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN Gibson County, Indiana Prepared by the Evansville Metropolitan Planning Organization LONG RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN Gibson County, Indiana ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GIBSON COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS Bob Townsend, President Gerald Bledsoe, Vice-President Alan Douglas, Member CITY OF PRINCETON UMBRELLA COMMITTEE Bob Hurst, Mayor Kelly Dillon, Toyota Motor Manufacturing Indiana Tim Burris, Hansen Corporation Peg Michas, Pride in Princeton Alan Douglas, Gibson County Commissioner Jason Spindler Kathy Cowling, Princeton Councilwoman Jami Allen, Fifth Third Bank Lynn Roach, WRAY Radio Gary Blackburn, Princeton Publishing Chris Hayes, Princeton Retail Merchants Helen Hauke Todd Mosby, Gibson County Economic Development Corporation Karen Thompson, Gibson County Chamber of Commerce Bob Shaw EVANSVILLE METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION Mr. Bradley G. Mills, Executive Director Mr. Vishu Lingala, Transportation Planner Mr. Craig Luebke, Transportation Planner Ms. Erin Mattingly, Transportation Planner TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 1 A. Study Background ........................................................................................................................................... 1 B. Gibson County Transportation Planning Area ............................................................................................... 1 C. Plan Purpose ................................................................................................................................................... -

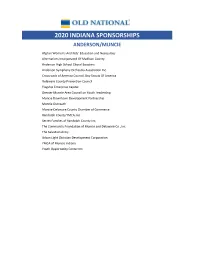

2020 Sponsorship Website Template.Xlsx

2020 INDIANA SPONSORSHIPS ANDERSON/MUNCIE Afghan Women's And Kids' Education and Necessities Alternatives Incorporated Of Madison County Anderson High School Choral Boosters Anderson Symphony Orchestra Association Inc. Crossroads of America Council, Boy Scouts Of America Delaware County Prevention Council Flagship Enterprise Capital Greater Muncie Area Council on Youth Leadership Muncie Downtown Development Partnership Muncie Outreach Muncie‐Delaware County Chamber of Commerce Randolph County YMCA, Inc. Secret Families of Randolph County Inc. The Community Foundation of Muncie and Delaware Co., Inc. The Salvation Army Urban Light Christian Development Corporation YMCA of Muncie Indiana Youth Opportunity Center Inc. BLOOMINGTON Amethyst House Inc. Bedford Clothe A Child Inc. Big Brothers Big Sisters of South Central Indiana Bloomington Health Foundation Bloomington PRIDE Boys and Girls Clubs of Bloomington Boys and Girls Club of Lawrence County Cardinal Stage Company Catholic Charities City of Bloomington Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday Celebration Commission Community Foundation of Bloomington and Monroe County Dimension Mill Inc. Dr Martin Luther King Commission City of Bloomington Ellettsville Chamber of Commerce Fairview Elementary School Foundation of Monroe County Community Schools Inc. Greater Bloomington Chamber of Commerce, Inc. Habitat for Humanity of Monroe County Indiana Hannah Center Inc. Hoosier Hills Food Bank Inc. Ivy Tech Foundation Kiwanis Club of South Central Indiana Lotus Education And Arts Foundation Inc. Monroe County Community School Corporation Monroe County YMCA Pantry 279 Inc. People and Animal Learning Services Inc. Radius Indiana Inc. Shalom Community Center Inc. Southern Indiana Exchange Clubs Foundation Inc. The Salvation Army of Monroe County United Way of Monroe County Indiana United Way of South Central IN/Lawrence County Wonderlab‐Museum Of Science Health and Technology Inc. -

Boonville Shopping Center

OFFERING MEMORANDUM BOONVILLE SHOPPING CENTER 802 W. MAIN ST | BOONVILLE, IN 47601 ™ LISTED BY CHUCK EVANS SENIOR ASSOCIATE DIRECT (310) 919-5841 MOBILE (925) 323-2263 [email protected] LIC # 01963473 (CA) BROKER OF RECORD KYLE MATTHEWS LIC # RC51700140 (IN) BOONVILLE SHOPPING CENTER OFFERING MEMORANDUM BOONVILLE SHOPPING CENTER 802 W. MAIN ST | BOONVILLE, IN 47601 04 | EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW 06 | PROPERTY OVERVIEW 10 | FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 14 | AREA OVERVIEW 3 SECTION I EXECUTIVE OVERVIEW 4 BOONVILLE SHOPPING CENTER INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS SALE PRICE: » Recently Extended Lease – Autozone just executed a lease $760,197.83 renewal until 2031 demonstrating a strong commitment to the site » Longevity of tenants – Most of the tenants in the shopping center have been there for the past 15 years » High Returns – True capitalization on an above market yield CAP RATE: 12.00% » Ideal placement – located on the main road from the city to the Walmart Supercenter which is the main shopping hub for the town » 19,000+ Vehicles per day » Capital Improvements: NOI: • Resurfaced and re-striped parking lot • The parking lot was cleaned, milled, and 350 tons of new asphalt $93,090.82 were laid on the parking lot. • 30% of roof was resurfaced with elastomeric coating • All parking lot and canopy lights replaced with LED lights and Four LED solar powered lights were installed as well. • In total, $86,000 were invested to improve the center in preparation for a sale. 5 SECTION II PROPERTY OVERVIEW 6 BOONVILLE SHOPPING CENTER PARCEL MAP PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION -

I LOVE, Ycqmmunitv SERVICE

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. \ THE I LOVE,yCQMMUNITV SERVICE I COOKBOOK Easy-to-do recipes for community service that combine service-learning with Youth as Resources projects. This publication is made possible by the National Crime Prevention Council, the Indiana Department of Education, Youth Resources of Southwestern Indiana, the Evansville Courier Company, and Krieger-Ragsdale & Company. First Printing April,1994 Second Printing October, 1994 COPYRIGHT ©1994 YOUTH RESOURCES OF SOUTHWESTERN IN "Helping others really gave me a warm feeling. It really opened my eyes to the poverty that's right around me. It's not just in New York and L.A. - it's here in Evansville. Aislln Arney Harrison High School History Class Project with Christian Life Center () () "One thing I'm going to do differently because of the Helping Hands project is to help people Who are in need, and not look down on them." Jamie Benefiel, Harrison High School Ii "It [the project] made me feel happy. I helped someone." o Jamila, Caze Elementary School First Aid From ttl'e First Grade "The hardest part was doing the work after school, but the best part was going to the day care center to work with the kids. It made me feel good." 8th Grader, McGary Middle School "I got a lot of pleasure watching how well my Exploring Childhood students worked with children. We were all touched by the hugs and 'I love yo us' when we left each place. I was"troubled to learn of the number of hours some children spend away from their families. -

Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Public Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln's Positions on Slavery

Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Public Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln's Positions on Slavery The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mcclelland, Edward. 2019. Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Public Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln's Positions on Slavery. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42004076 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Lincoln, Slavery and Springfield: How Popular Opinion in Central Illinois Influenced Abraham Lincoln’s Views on Slavery Edward McClelland A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University March 2019 !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Copyright 2018 [Edward McClelland] "!! ! Abstract Abraham Lincoln won the Republican nomination in 1860 because he was seen as less radical on the slavery than his rivals William Seward and Salmon P. Chase, and less conservative than Edward Bates. This thesis explores how his career as a politician in Central Illinois – a region that contained of mix of settlers from both New England and the South – required him to navigate between the extremes of the slavery question, -

University Library, University of Illinois

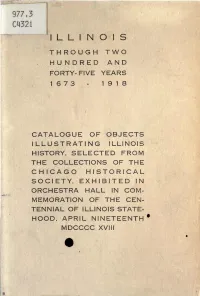

977.3 C4321 ILLINOIS THROUGH TWO HUNDRED AND FORTY- FIVE YEARS 1673 - 1918 CATALOGUE OF OBJECTS ILLUSTRATING ILLINOIS HISTORY, SELECTED FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF THE CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY, EXHIBITED IN ORCHESTRA HALL IN COM- MEMORATION OF THE CEN- TENNIAL OF ILLINOIS STATE- HOOD, APRIL NINETEENTH* MDCCCC XVIII OLD FLAGS OF ILLINOIS ILLINOIS REGIMENTAL FLAGS. Carried in the Civil War, by the 8th, 19th, 42d, 89th, and 129th Regiments, the last men- tioned being a relic of Sherman's March to the Sea. Loaned by the Grand Army Hall and Memo- rial Association of Illinois. UNITED STATES ZOUAVE CADETS. Champion flag awarded in 1859. This organization founded by Col. Elmer E. Ells- worth in the middle fifties was adjudged the best drilled body of men in the country. At the beginning of the war it was disbanded, being drawn upon to officer regi- ments all over the country. Colonel Ellsworth organized the New York Fire Zouaves and met his tragic death in guarding the approach to Washington. LINCOLN-ARNOLD BANNER. Given by President Lincoln to Hon. Isaac N. Arnold. The square in the center is from the battle flag of an unknown Illinois Regiment. CHICAGO RAILROAD BATTALION. Flag under which this battalion was recruited in 1862, after Lincdn's call for "300,000 more." Letters and Documents Signed by Explorers, Governors and Statesmen of Illinois 1673-1871 1. EXPLORATION, 1673-1682. JOLLIET, Louis, 1(145-1699 or 1700. Contract executed by Louis Jolliet, his wife, her brothers and others, at Quebec, Nov. 8, 1695. Jolliet, a trader, a native of Quebec, was chosen by Frontenac to explore the Mississippi, since he was "a man very experienced in these kinds of discoveries and who had already been very near this invert' With Father Marquette as his priest-associate, he descended the Wis- consin and Illinois Rivers, and entered the Mississippi, June 17, 1673. -

Download Download

Faulting in Posey and Gibson Counties, Indiana Curtis H. Ault, Dan M. Sullivan, and George F. Tanner Indiana Geological Survey, Bloomington, Indiana 47405 Introduction and History of Study In the fall of 1977 we began our investigation of the Wabash Valley Fault System to help characterize the tectonic processes in southwestern Indiana. It was part of a project funded by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission for geologists and geophysicists from various universities and geological surveys to study the tectonics, seismicity, and structure of the area within a 200-mile radius of New Madrid, Missouri. Since the early 1900's more than 6,000 petroleum test wells and other tests have been drilled in Posey County and southern Gibson County, which contain nearly all known faults of the Wabash Valley Fault System in Indiana. Detailed subsurface structural mapping by petroleum companies was conducted from the 1930's and 1940's until the late 1960's, when oil activity declined. But these studies have been proprietary, and the companies have released little or no structural data. Further, oil companies have usually focused attention on the reservoir rocks near the faults rather than on the complexity of the faults themselves. Part of the Ridgway Fault of the Wabash Valley Fault System in Illinois was early described by Cady in 1919 (4). As drilling for petroleum and mining for coal progressed in Illinois, the fault system was further defined in county reports and maps and other fault studies (Stonehouse and Wilson (11) for example). The most recent mapping of the faults in Illinois was completed by Bristol and Treworgy in 1979 (2).