Peer Mentoring, Newman University 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] [email protected]

NUCCAT Members 2015/2016 N.B. bold type denotes main or only representative; Board members highlighted by grey shading Institution Representative Position Address e-mail Address/Telephone Head of Academic Policy and University of Birmingham Gillian Davis Registry, University of Birmingham, B155 2TT [email protected] I Standards T: 0121 414 2807 University of Bolton, Deane Road, Bolton, University of Bolton Richard Gill Quality Assurance Manager [email protected] I BL3 5AB T: 01204 903242 Head of Learning Enhancement and University of Bolton, Deane Road, Bolton, BL3 University of Bolton Dr Marie Norman [email protected] I Student Experience 5AB T: 01204 903213 University of Bolton Dr Anne Miller Academic Registrar University of Bolton Deane Road, Bolton, BL3 5AB [email protected] T: 01204 903832 Professor Gwendolen Director of Quality Enhancement Academic Standards & Support Unit, University of Bradford [email protected] Bradshaw and Standards Univeristy of Bradford, Richmond Road, I Bradford, BD7 1DP T: 01274 236391 Academic Standards & Support Unit, Univeristy Director of Academic Quality and University of Bradford Ms Celia Moran of Bradford, Richmond Road, Bradford, BD7 [email protected] Partnership 1DP T: 01274 235635 Academic Standards & Support Unit, Univeristy University of Bradford Laura Baxter Academic Quality Officer of Bradford, Richmond Road, Bradford, BD7 [email protected] 1DP T: 01274 235085 Unviersity College University College Birmingham, Summer Mr Robin Dutton Director of Quality Systems -

Prospectus Perseverance / Character / Hope Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel College

Immanuel College Prospectus Perseverance / Character / Hope Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel College Immanuel College Post 16 was the natural step for me and many of my peers from year 11. We find the support and teaching to be excellent and we are treated more like adults. I enjoy studying the subjects I’m passionate about. “Year 12 Student Opportunities and lessons have made me step outside my comfort zone in year 12. I now have a career goal thanks to the support I’ve received in post 16. ” Current student Welcome to “ Immanuel College Post 16 We are very proud of Immanuel College post 16 and the outstanding achievements of our students. We have had another record year at A-level with a quarter of grades being A/A*. At Immanuel College we offer a broad range of high quality courses to suit every learner ” alongside a rich choice of extracurricular activities that will develop skills and talents. Each year our students gain their first choice Immanuel university places or take up employment opportunities, progressing successfully to their next step. e eg ll Co I joined Immanuel College in year 12 and I’m pleased to say the teaching and results are everything I hoped for. It’s a successful school with a good reputation in the area. “Year 12 Student ” Perseverance / Character / Hope 1 Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel College Post 16 / Prospectus Immanuel Immanuel e eg ll Co College We are a truly comprehensive school and welcome applications Romans 5:4 from all learners. Our success is the result of our dedicated, caring Perseverance produces character; and supportive teachers, tutors and leaders who work within a strong Christian community. -

Access & Participation Plan 2019-20

York St John University Access & Participation Plan 2019-20 Access & Participation Plan 2019-20 York St John University A history of widening access York St John University has been widening access to higher education since its founding as a Teacher Training College by the Church of England in 1841: “…as the most powerful means of remedying the existing defects in the Education both of the Poor and Middle Classes of Society, to establish a School for the purpose of Training Masters in the Art and Practice of Teaching.” This has underpinned our approach ever since, as can been seen in the development of our latest Strategic Plan. Contents Section 1 Assessment of current performance 2 Section 2 Ambitions and Strategy 7 Section 3 Targets 10 Section 4 Access, success and progression measures 10 Section 5 Investment 19 Section 6 Provision of information to students 19 Appendix Students’ Union submission 20 1 York St John University Access & Participation Plan 2019-20 1. Assessment of current performance Our size and shape York St John University currently has 5,100 APP-countable students (paying Home/EU fees and studying on UG Degree, Foundation Degrees or PGCE courses). Figure 1 shows how this overall student population is broken down into the five underrepresented groups identified by the Office for Students (OfS) and the intersections between those groups: Figure 1 Understanding our student population in terms of underrepresented groups and their intersectionality (as at 1 February 2018) The largest of our underrepresented groups is the POLAR quintiles 1 and 2 metric. POLAR looks at how likely young people are to participate in Higher Education (HE). -

North East, Yorkshire and Humber Regions, but There Are Many More to Range of Subjects on Offer, Direct Explore All Over the UK

WHAT CAN YOU STUDY? There are around 37,000 different higher education courses on offer in the UK. These Thinking about courses can lead to qualifications such as degrees, Foundation degrees, Higher National Diplomas and Certificates. You may decide to continue a subject that you’re already familiar with, such as English, higher education? History, Mathematics or French, or you may want to try something completely new, like Archaeology, Town Planning, Pharmacology or Creative Multimedia. If you have a particular career in mind, then you might need to study a specific course, such as Medicine or Engineering. Many universities and colleges even offer you the chance to combine two or three different subjects. Are you thinking about what to do after you finish school or college? With so much to choose from, the most important thing is to research thoroughly what’s available and decide what interests you the most. The perfect course might be something Have you thought about continuing your studies at a university or you have yet to read about. college of higher education? WHERE CAN YOU STUDY? To help get you started, this Finding the right course isn’t the only decision you have to make. You also have over 300 leaflet will answer some of your universities and colleges to choose from. This leaflet will introduce you to some of the questions, introduce you to a institutions in the North East, Yorkshire and Humber regions, but there are many more to range of subjects on offer, direct explore all over the UK. Leeds College of Art you to where you can find out Leeds Beckett University Students choose a particular university or college for many different reasons including more and provide information Leeds Trinity University distance from home, reputation, geographical location and facilities. -

Study Abroad for Economics Majors

Study Abroad in Movement & College of Health Exercise Science, Professions Rehabilitation Sciences: School of Movement and Pre-PT & Pre-AT Majors Rehabilitation Sciences Flynn Building 502-742-4915 “The opportunities Bellarmine University provides for students in the School of http://www.bellarmine.ed Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences (i.e. doctor of physical therapy, exercise science, u/lansing/exercisescience/ and master’s in athletic training) allow for personal, intellectual and professional growth. Students and faculty experience different cultures and appreciate different Faculty Liaison for perspectives on health, wellness, and the management of acute and chronic disease and Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences disabilities. Students learn to challenge their ideas and biases about health and health care Dr. Thomas Wójcicki systems, apply their knowledge and skills in culturally diverse environments, and Flynn 111 understand their individual roles and responsibilities to the global community as future [email protected] clinicians, practitioners, researchers, and professionals. Study abroad is clearly one of the best ways to acquire skills necessary for future success in a global community.” Office for Study Abroad Dr. Tony Brosky, Dean-School of Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences & International Learning, Horrigan Hall 111 502-272-8479 Study Abroad as an Exercise Dr. Gabriele Weber-Bosley, Science Major and . Executive Director [email protected] • Learn firsthand about global trends in the fields Exercise and Physical -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies MATEOS-GONZALEZ, JOSE,LUIS How to cite: MATEOS-GONZALEZ, JOSE,LUIS (2019) Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13359/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Non-EU International Students in UK Higher Education Institutions: Prosperity, Stagnation and Institutional Hierarchies José Luis Mateos-González Department of Sociology, Durham University A thesis submitted to Durham University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2019 1 To my mum –her unconditional support has made this thesis possible. A mi madre, cuyo apoyo incondicional ha hecho de esta tesis una realidad. To my dad –I will always miss him. -

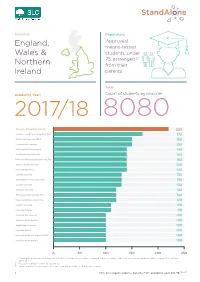

FOI 158-19 Data-Infographic-V2.Indd

Domicile: Population: Approved, England, means-tested Wales & students, under 25, estranged [1] Northern from their Ireland parents Total: Academic Year: Count of students by provider 2017/18 8080 Manchester Metropolitan University 220 Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) 170 De Montfort University (DMU) 150 Leeds Beckett University 150 University Of Wolverhampton 140 Nottingham Trent University 140 University Of Central Lancashire (UCLAN) 140 Sheeld Hallam University 140 University Of Salford 140 Coventry University 130 Northumbria University Newcastle 130 Teesside University 130 Middlesex University 120 Birmingham City University (BCU) 120 University Of East London (UEL) 120 Kingston University 110 University Of Derby 110 University Of Portsmouth 100 University Of Hertfordshire 100 Anglia Ruskin University 100 University Of Kent 100 University Of West Of England (UWE) 100 University Of Westminster 100 0 50 100 150 200 250 1. “Estranged” means the customer has ticked the “You are irreconcilably estranged (have no contact with) from your parents and this will not change” box on their application. 2. Results rounded to nearest 10 customers 3. Where number of customers is less than 20 at any provider this has been shown as * 1 FOI | Estranged students data by HEP, academic year 201718 [158-19] Plymouth University 90 Bangor University 40 University Of Huddersfield 90 Aberystwyth University 40 University Of Hull 90 Aston University 40 University Of Brighton 90 University Of York 40 Staordshire University 80 Bath Spa University 40 Edge Hill -

Post 18 Option Choices Evening – Presentations

Post 18 Option Choices Evening – Presentations Y12 Parents - Please book these presentations on ParentPay. All presentations are at 5.30pm and 6.30pm. Organisation Speaker Presentation Topics Room Apprenticeships CYC Beverley Wills How Apprenticeships Work En1 Studying at Askham Bryan Askham Bryan College Rob Wilson En2 General Information on University of Huddersfield Jane Murphy En3 the University of Huddersfield Studying at Lancaster University Michaela Lowerson Ma2 Lancaster University Leeds Beckett University Rob Rattray The University Application Process Ma3 Student Life/Expectations Newcastle University Sophie Bennett The Unique Student Experience Ma4 in Newcastle Application Process Student Finance Northumbria University Lisa Shannon Choosing a Course HSC Choosing a University Accommodation University of Oxford Dr Dave Leal Interviews/ Admissions RE1 Student Finance Why Choose Higher Education? Sheffield Hallam University Becki McKechnie RE2 Why Choose Sheffield? UCAS process University of Hull Amy Newton Studying at the University of Hull ME Supporting Your Child: Admissions University of Leeds Amy Wilson RE3 Student Finance Accommodation Applying to Higher Education Russell Group Universities University of Sheffield Suzie Murray How to Give a Competitive Edge to your NBM University Application Student Life University of York Lorna Bowling Life at the University of York NBPE University of St Andrews University of St Andrews Kirsty McDonald Studying in Scotland NBS Studying Chemistry York St John University Zack Sizer Studying at York St John NBE Ex All Saints Student at Pembroke College, Oxford. In her final year of studying a 4 year Jess Ellins integrated Masters in Bio-Chemistry. NB6 Starting a PhD at Imperial College in September 2019. The Alcohol Trust Practical advice for parents and students. -

College and University Acceptances

COLLEGE AND UNIVERSITY ACCEPTANCES 2016 -2020 UNITED KINGDOM • University of Bristol • High Point University • Aberystwyth University • University of Cardiff • Hofstra University • Arts University Bournemouth • University of Central Lancashire • Ithaca College • Aston University • University of East Anglia • Lesley University • Bath Spa University • University of East London • Long Island University - CW Post • Birkbeck University of London • University of Dundee • Loyola Marymount University • Bornemouth University • University of Edinburgh • Loyola University Chicago • Bristol, UWE • University of Essex • Loyola University Maryland • Brunel University London • University of Exeter • Lynn University • Cardiff University • University of Glasgow • Marist College • City and Guilds of London Art School • University of Gloucestershire • McGill University • City University of London • University of Greenwich • Miami University • Durham University • University of Kent • Michigan State University • Goldsmiths, University of London • University of Lancaster • Missouri Western State University • Greenwich School of Management • University of Leeds • New York Institute of Technology • Keele University • University of Lincoln • New York University • King’s College London • University of Liverpool • Northeastern University • Imperial College London • University of Loughborough • Oxford College of Emory University • Imperial College London - Faculty of Medicine • University of Manchester • Pennsylvania State University • International School for Screen -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1 Report introduction................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2 The Erasmus Mundus project (2012-2015) ............................................................................................................................... 2 2.1 Handbook conceptual approach ...................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Open source handbook ................................................................................................................................................... 2 3 The Social and Solidarity Economy Conference ........................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 Conference theme ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Conference aim and objectives ....................................................................................................................................... 3 3.3 Conference methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 4 3.4 Project and conference acknowledgements (in alphabetical order by surname) ........................................................... 4 3.5 -

The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press on Behalf of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

© The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. All rights reserved. This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Schizophrenia Bulletin following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version Jardri, R., Hugdahl, K., Hughes, M. et al. 2016. Are Hallucinations Due to an Imbalance Between Excitatory and Inhibitory Influences on the Brain? Schizophrenia Bulletin is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw075 1 2 3 Are Hallucinations Due to an Imbalance Between Excitatory and Inhibitory Influences on the Brain? 4 5 6 7 8 Renaud Jardri1,*, Kenneth Hugdahl2, Matthew Hughes3, Jérôme Brunelin4,5, Flavie Waters6, Ben 9 10 Alderson-Day7, Dave Smailes8, Philipp Sterzer9, Philip R. Corlett10, Pantelis Leptourgos11, Martin 11 12,13 14 11 12 Debbané , Arnaud Cachia , Sophie Denève . 13 14 15 16 17 1. Univ Lille, CNRS UMR 9193, SCALab (psyCHIC team) & CHU Lille, Psychiatry Dpt. (CURE), Lille, France 18 2. University of Bergen, Dpt. Biological and Medical Psychology & Division of Psychiatry/ Dpt. of Radiology, Haukeland University 19 Hospital, Bergen, Norway 20 3. Swinburne University of Technology, Brain & Psychological Sciences Centre, Melbourne, Australia 4. Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherche en Réadaptation et en Intégration Sociale (CIRRIS), Université Laval, Québec (Qc), Canada 2221 23 5. Université Lyon 1, INSERM U1028 & CNRS 5292, Lyon Neuroscience Research Centre (ΨR2 team), Centre Hospitalier Le Vinatier, 24 Lyon, France 25 6. School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, University of Western Australia, and Clinical Research Centre, Graylands Health 26 Campus, North Metropolitan Area Health Service Mental Health, Perth, Australia 7. -

Maryvale Director to Speak at Leeds Trinity University College Conference on New Evangelisation Posted on April 29, 2012 by Anthony Athanasius Mgr

Maryvale Director to speak at Leeds Trinity University College conference on New Evangelisation Posted on April 29, 2012 by Anthony Athanasius Mgr. Paul Watson, Director of Maryvale Higher Institute of Religious Sciences, is to speak at the international conference to be held at Leeds Trinity University College, ‘Vatican II 50 years on: The New Evangelisation’, 26-29 June 2012. ‘The fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of the Second Vatican Council provides a unique opportunity to revisit that seminal event which had such a profound impact on the life of the Catholic Church and its mission. In particular, the Council began an engagement with the modern and secularized world through a renewed proclamation of the Gospel. Blessed John Paul II described this as the ‘new evangelization’, and in 2010, Pope Benedict XVI confirmed this priority by creating the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization.’ ‘In order to reflect on the impact of Council and deepen understanding of the New Evangelization, Leeds Trinity University College is hosting an international Catholic theological conference on 26-29 June 2012 in the city of Leeds, UK. It is being organised by Leeds Trinity in conjunction with the Centre for Catholic Studies at Durham University. This is the first in a series to celebrate Catholic Higher Education in the UK.’ ‘Francis Cardinal George, Archbishop of Chicago, Fernando Cardinal Filoni, Prefect for the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, Archbishop Salvatore Fisichella, President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization, Professor Gavin D’Costa of Bristol University, Professor Tracey Rowland of the John Paul II Institute in Melbourne, Professor Susan Wood of Marquette University, Professor Mathijs Lamberigts of Leuven University, Professor Paul Murray of Durham University, Dr Richard Baawobr, Superior General of the Missionaries of Africa, and other high profile church leaders and theologians from different parts of the world will address the conference.