Marcelle Bienvenu Transcript Edited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lunch Express All Plates Are $12 and Include 2 Sides. Main Dishes Sides

Lunch Express All Plates are $12 and include 2 sides. Pick any Main Dish, or a Daily Special along with two sides, unless otherwise stated. Delivered to your table fast, so you can get back to work or play in a hurry. Main Dishes Cuban BBQ Pork Fried Catfish Beef Grillades Fried or Broiled Shrimp Steak Palomino Grilled “Mojo” Chicken Breast Chicken Etouffée Shrimp Creole & White Rice (w/1 side) Shrimp & Grits (with 1 side) Sides Black Beans & Coconut Rice Broccoli Slaw White Rice Sidewinder Fries Coconut Rice Corn Maque Choux Southern Greens Garlic Mashed Potatoes Fried Plantain Chips Smothered Squash Cheese Grits Daily Specials MONDAY Smothered Chicken Stuffed Bell Peppers Half a chicken smothered in a rich dark southern gravy. Seasoned ground beef, pork and rice tucked in roasted bell peppers topped with Creole sauce. TUESDAY Round Steak Stuffed Eggplant Slowly cooked down with the holy trinity in a rich, Ground beef, ground pork, Gulf shrimp and rice stuffed eggplant dark roux onion gravy. with Creole sauce. WEDNESDAY Smothered Pork Chops Creole Beef Daube Two slow braised chops in delta-style onion gravy. Marinated pot roast, slow roasted to tender perfection in red Creole gravy. THURSDAY Liver and Onions Lechón a la Cubana Sautéed calf liver just like at Grandma’s house. Slow roasted pork marinated in sour orange and Cuban spices. FRIDAY Fried Flounder Filets Shrimp Etouffée Local flounder, perfectly flash fried. A Creole classic, shrimp smothered in a richly seasoned tomato gravy. *The consumption of raw and undercooked foods such as meat, poultry, seafood, shellfish and eggs may increase your risk of food-borne illness, especially if you have a medical condition. -

Soup Du Jour Cup -4- Bowl -7- Gumbo Du Jour Cup -4

Spicy Chicken Soup du Jour cup -4- bowl -7- Fried chicken breast topped with Pepper Jack cheese, sriracha paste, Gumbo du jour cup -4- bowl -7- bacon, and spicy Aioli served on ciabatta bun with hand cut fries -12- Chicken Wings Regular Burger 6 for $8 / 12 for $12 2 thin patties on brioche bun with hand cut fries -8- (Naked / BBQ / Honey-Sriracha / Buffalo) Add cheese +.50 Dressed+1.50 (cheese,lettuce,tomato,ketchup, mustard) Cajun Fried Mushrooms Cajun fried mushrooms served with spicy Aioli for dipping -11- Cote Burger 2 thin patties layered with American cheese and caramelized onions Dirty Fries on top of lettuce, tomatoes, and creole Aioli Hand cut fries topped with red onions, jalapenos, and served on a brioche bun with hand cut fries -12- Cochon de Lait and broiled with cheddar cheese -10 (add gravy +2) BBQ Bacon Burger 2 thin patties topped with house BBQ sauce and Applewood smoked Spinach, & Artichoke Dip bacon broiled with Cheddar cheese and dressed with pickle and Traditionally prepared spinach and artichoke dip, mustard served on a Brioche bun with hand cut fries --13- served with fried pasta strips -11- A1 Steakhouse Burger Fried Green Tomatoes & Blackened Shrimp House ground filet and ribeye pieces, hand pattied, topped with fried Fresh green tomatoes fried golden brown, topped with blackened shrimp over Steen’s cane syrup reduction onion strings, Applewood smoked bacon, and Pepper Jack cheese and finished with house Remoulade -13- dressed with garlic Aioli served on a Brioche bun with hand cut fries -13- House Salad Lettuce, -

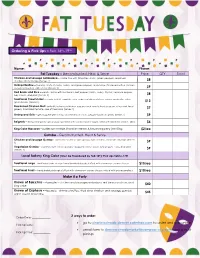

Ordering & Pick Ups – Feb 16Th–19Th

Ordering & Pick Ups – Feb 16th–19th Name: Phone: Fat Tuesday – Deconstructed, Heat & Serve Price QTY Total Chicken and Sausage Jambalaya – creole rice with tomatoes, onion, green peppers, seasoned chicken, and sausage (Serves 1) $8 Shrimp Etouffee – the Holy Trinity of onion, celery, and green pepper, and shrimp, thickened with a chicken roux served with a side of rice (Serves 1) $9 Red Beans and Rice – creole cuisine with red beans, bell pepper, onion, celery, thyme, cayenne pepper, bay leaves, and pork (Serves 1) $8 Traditional Crawfish Boil – ready to boil, crawfish, corn cobs, red skin potatoes, onions, andouille, citrus, green beans (Serves 1) $12 Blackened Chicken Melt- grilled blackened chicken, pepper jack, roasted red peppers, citrus aioli, local greens, marinated tomato, side of fried okra (Serves 1) $7 Shrimp and Grits – grits topped with shrimp simmered in a onion, pepper & bacon gravy (Serves 1) $9 Beignets – deep fried pastry generously sprinkled with confectioners’ sugar, filled with Bavarian cream (4ct) $4 King Cake Macaron – butter rum cookie, Bavarian cream & house raspberry jam filing $2/ea Gumbo – Deconstructed, Heat & Serve Chicken and Sausage Gumbo - authentic southern style gumbo with chicken, andouille sausage (Serves 1) $9 Vegetarian Gumbo - southern style creole gumbo chopped celery, onion, bell pepper, corn, and okra (Serves 1) $9 Local Bakery King Cake (Must be Preordered by Feb 10th)! Pick Ups Feb16-17th Traditional Large - traditional cake version hand braided dough stuffed with cinnamon-cream cheese $15/ea -

Sides Boiled Favorites Gumbo, Salad & More Gulf Oysters Appetizers

ONLINE ORDERING AVAILABLE WWW.REELCAJUNSEAFOOD.COM @reelcajunseafood /reelcajunseafood Appetizers Gumbo, Salad & More RC SAMPLER 20 Ranch, Italian, Thousand Island, Honey Mustard & Raspberry Vinaigrette Cajun egg rolls, shrimp rolls, boudain Add pistolette roll + 1 balls, pot stickers, and fried pickles. CHICKEN & SAUSAGE GUMBO CRAWFISH ÉTOUFFÉE POTSTICKERS 8 Served with potato salad. Small 5.95 | Large 10.95 Small 5.95 | Large 10.95 REEL CAJUN LINGUINE 13.95 FRIED ALLIGATOR 11 SEAFOOD GUMBO Linguine pasta tossed in our creamy Alfredo Served with potato salad. sauce, then topped with blackened shrimp, SHRIMP ROLLS 7 Small 6.95 | Large 12.95 house sauce and scallions. SHRIMP SALAD 13.95 BLACKENED CHICKEN GOOD TIMES FRIES 8 Served grilled or blackened with LINGUINE 11.95 fresh spring mix, grape tomatoes, Linguine pasta tossed in our creamy Alfredo CRAB CAKES (2) 12 shredded cheese and garlic croutons. sauce and topped with a blackened chicken breast. GRILLED CHICKEN SALAD 12.95 CAJUN EGGROLLS 8 Freshly prepared spring mix tossed with GARLIC NOODLES Cajun pecans, dried cranberries and WITH SHRIMP 12.95 BOUDAIN BALLS 9 crumbled goat cheese. Sautéed pasta tossed with garlic butter, SHAKEN BEEF SALAD 13.95 grilled shrimp, and green onions. SEARED AHI TUNA 11 House marinated sirloin sautéed with STUFFED BAKED POTATO 7.95 onions over spring mix, grape tomatoes, Freshly baked potato stuffed with fried, green onions and garlic croutons. grilled or blackened shrimp, butter, sour FRIED CHEESE 6 cream, cheese and green onions. Make it a gator tater + 2 CALAMARI FRIES 7 SWEET POTATO FRIES 7 Boiled Favorites FRIED PICKLES 6 All boiled seafood is MARKET PRICE and is subject to change, please ask server for details. -

Voodoo Gumbo

Appetizers Bucky’s Specialties Fried Seafood Sandwiches Happy Hour Sandwiches served with french fries Fried Green Tomatoes- Catfish Pontchartrain- Chicken & Waffles- Fried Catfish Fillets- Blackened or fried Catfish topped with The best Belgian waffle ever made topped Chicken Fried Steak Sandwich- Specials Hand battered and fried to perfection.......8.25 2 hand battered American catfish fillets crawfish in my amazing signature sauce and with real butter and served with maple syrup. cooked to perfection. Served with French fries Hand battered top round steak served on Hours:Tuesday - Friday 4-7 served over white rice...........................18.50 and jalapeno hushpuppies.......................13.50 Brioche with Lettuce, tomato and side of Boudin Balls- With 3 chicken tenders Lunch portion.....................................14.50 or 3 large chicken wings...........................13.50 cream gravy.............................................12.50 Thursday All Day Braised pork, rice, spices and herbs battered With chicken & veggies.......................13.50 Fried Jumbo Shrimp- and fried to perfection...............................8.25 Memphis Chicken & 6 butterflied Gulf Shrimp hand battered in Bucky’s Burger- $3 domestic bottles Atchafalaya- our signature saltine batter and fried to Jalapeno Waffle- Ground Brisket and Chuck cooked to order Cajun Chips and Queso- Blackened or fried Catfish topped with perfection. Served with French fries and Memphis dipped chicken with Jalapeno Corn served on Brioche Bread with lettuce, mayo $4 import -

Hors D'oeuvres & Appetizers

CATERING MENU Hors d’oeuvres & Appetizers Fish Tuna Sashimi with pickled ginger, seaweed, wasabi and soy glaze Sesame seared Tuna and watermelon skewers with caramel soy Tuna tartare on wonton with mango and siracha Hamachi ceviche with candied jalapenos and yuzu foam Smoked salmon bruschetta with Boursin capers and red onion Smoked salmon on blinis with crème fraiche and dill Smoked salmon on lavash cracker with truffle caviar and cucumber Salmon skewers with maple mustard and citrus brown butter Salmon wellington with mushroom duxelle and gorgonzola Grouper bites with chipotle remoulade dipping sauce Sturgeon caviar with capers, tomato, onion, separated egg and blinis Shellfish Chilled jumbo shrimp with tequila lime cocktail sauce Dueling pesto grilled shrimp with tomatoes and basil Prosciutto wrapped prawns with chili mango chutney Coconut crusted shrimp with pineapple marmalade House garlic shrimp with chili butter and white wine Lemongrass curry shrimp with lime and coconut foam Seared scallop with a smoked pepper bacon jam Seared sea scallop wrapped with applewood smoked bacon Mini crab cakes with siracha aioli and cilantro Crab stuffed mushroom caps with a sherry cream sauce Cold lobster cocktail with fresh fennel, mango, orange supreme and watercress Fried lobster bites with a chili orange glaze and lemon pepper Sautéed lobster bites en croute, puff pastry and creamed garlic butter Jumbo lump crab martini with whole grain mustard remoulade Oyster shooter with yuzu, champagne, cocktail sauce and micro horseradish Fried oyster bite -

Holiday Recipes © 2017 WWL-TV

Holiday Recipes © 2017 WWL-TV. All rights reserved. Recipes on pages 17-87 appear with permission of WWL-TV, the Frank Davis family, and Kevin Belton. Recipes on pages 90-96 appear with permission of Cajun Country Rice and recipe authors. Cajun Country Rice Logo and MeeMaw appear with permission of Cajun Country Rice. Southern Food and Beverage Museum Logo and National Food & Beverage Foundation Culinary Heritage Register Logo appear with permission of Southern Food and Beverage Museum. IN THE KITCHEN | WWL-TV | WUPL Table of Contents Introduction Chef Kevin Belton Frank Davis 10 12 13 What is SoFAB? Sausage Bites Sweet Tater Casserole 15 17 19 Franksgiving: Mayflower-Style Sausage Stuffing with Smothered Creamed Spinach Turkey-Oyster Sauce Okra & Tomatoes 21 23 25 © 2017 WWL-TV. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. | 3 IN THE KITCHEN | WWL-TV | WUPL Table of Contents Shrimp & Crab Creole Tomatoes Candied Yams Stuffed Bell Peppers 27 29 31 Sicilian Stuffed Frank's Oyster Dressing Oyster Patties Vegetables 33 35 37 Naturally Noel: Oysters Mac & Cheese Vegetables & Rice 39 41 43 4 | © 2017 WWL-TV. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. IN THE KITCHEN | WWL-TV | WUPL Table of Contents Franksgiving Past: Cabbage & Sausage Trinity Dirty Rice Casserole 45 47 49 Black Eyed Peas White Beans & Shrimp Stuffed Mirliton 51 53 55 African Connections – Frank's Turkey Okra Gumbo Okra and Gumbo Andouille Gumbo 57 59 61 © 2017 WWL-TV. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. | 5 IN THE KITCHEN | WWL-TV | WUPL Table of Contents Potato, Shrimp & Ham with Cane Spinach Salad Cheddar Soup Syrup Glaze 63 65 67 Gourmet Naturally Noel: Franksgiving N'Awlins French-Fried Christmas Goose Slow-Roased Turkey Turkey 69 71 73 Frank's Christmas Eggnog Brisket with Holiday Paneed Pork Loin Bread Pudding Broasted Yams 75 77 79 6 | © 2017 WWL-TV. -

DAT Good Stuff Po-Boy's Boudin Boils Fries Combeauxs

Boudin B'z Boudin Ballz 5.99 rice, pork, chicken, garlic, poblano pepper, rolled, hand battered & deep fried & drizzled w/ breaux sauce DAT good stuff total of (3) ballz stuffed w/ pepper jack cheese (PJC) 6.75 ChIcKeN & AnDoUiLlE SaUsAgE GuMbO 9.99 dark roux, white rice, chicken & andouille sausage, garnished w/ green onyon' Smoked Boudin BREAD FOR DIPPIN' +1.00 Links 3.50 each ShRiMp PlAtTa 12.50 traditional hickory smoked boudin link (7) breaux battered gulf shrimp w/ cajun seasoned fries and breaux sauce for dippin' ReD BeAnS & RiCe 7.99 Fries white rice, red beans, diced andouille sausage, garnished w/ green onyon' Slap Ya Daddy CrAwFiSh ÉtOuFfÉe 13.50 Fries 5.50 blonde roux, white rice, crawfish tails sautéed in the cajun holy trinity, garnished garlic, parmesan, breaux sauce, green with green onyon onion garnish BREAD FOR DIPPIN' +1.00 Slap Ya Daddy SmOtHeReD CaT-DaDdY 14.99 breaux battered catfish on a bed of long and fancy white rice smothered w/ "Harder" Fries 10.50 crawfish étouffée and garnished with green onyon' (SYD) fries topped with crawfish EXTRA CATFISH FILET +2.75 étouffée, our house made signature slaw & garnished w/ green onion Combeauxs The Dirty "Berty" 12.50 SeAfOoD DiNnEr CoMbEaUx 13.99 (SYD) fries topped w/ crawfish (2) breaux battered catfish, (4) gulf shrimp, w/ cajun seasoned fries, our house étouffée, red beans, chicken & signature slaw w/ tarter & breaux sauce for dippin' andouille sausage (from gumbo) & garnished w/ green onion CaT-PaPpY PlAtTa 10.99 (2) breaux battered catfish, w/ cajun seasoned fries, -

Louisiana Cooking : Easy Cajun and Creole Recipes from Louisiana Pdf, Epub, Ebook

LOUISIANA COOKING : EASY CAJUN AND CREOLE RECIPES FROM LOUISIANA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sarah Spencer | 94 pages | 06 Dec 2017 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781981482276 | English | none Louisiana Cooking : Easy Cajun and Creole Recipes from Louisiana PDF Book No trivia or quizzes yet. Have all the ingredients prepped before you start cooking. By thedailygourmet. More filters. Tammy Chmielewski is currently reading it Jan 12, Louis Peanut Butter Pie recipe. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. Karen D Olanlege added it Dec 20, Boudin Balls. Ingredients: 2 pints fresh Louisiana oysters in liquid 1 lb. Brandon Bales. If you prefer not to make cornbread from scratch, use 4 cups diced prepared cornbread. Give your deviled egg recipe a dose of Creole flair with shrimp, spicy mustard, and lots of garlic. You can make one of the most iconic restaurant dishes in America right in your own kitchen. Creole cookbook. I decided to simplify this recipe to use the rice as a side to the catfish rather than make it the main course—though I plan to do that later, so stay tuned! For foodies, Louisiana is great not only when it comes alive in the spring , but any time of year. A traditional Crawfish Pie recipe that originated in the town of Napoleonville. Cook your shrimp in bacon fat and we promise, you'll never look back. Shrimp Creole. Get the recipe from Simple Sweet Recipes. Cook your shrimp in bacon fat and we promise, you'll never look back. Of course, Louisiana is proudly home to the Cajun and Creole recipes Southerners love. -

Cajun ~ Creole Cooking

CAJUN ~ CREOLE COOKING The French Cajuns fled British rule in the 18th century because of religious persecution and settled in bayous. They lived and cooked off the land, creating one-pot dishes such as gumbo, jambalaya and e’touffe’e. New Orleanians of European heritage, adapted classic French cooking with creations like baked fish in papillot (paper) and oysters Rockefeller. A Cajun gumbo is thickened with a dark roux and file’ powder whereas a Creole gumbo is thickened with okra and tomatoes. This is just one of the differences that Acadians argue over when it comes to traditional foods. The next few pages will describe traditional Cajun cuisine. Ándouille (ahn-do-ee) is a smoked sausage stuffed with cubed lean pork and flavored with Dirty rice is left-over rice that is pan-fried and vinegar, garlic red pepper and salt. This spicy sauteed with green peppers, onion, celery, stock, sausage is usually used in gumbo. liver, giblets and other ingredients. Beignet (ben-yea) are delicious sweet donuts that Étoufée (ay-too-fay) is a tangy tomato-based are square-shaped and minus the hole. They are sauce which usually smothers shrimp or crawfish. lavishly sprinkled with powder sugar. Filé powder (fee-lay) is ground dried sassafras Boudin (boo-dan) is the name for blood sausage. leaves and was first used by Native Americans. It It is a hot, spicy pork mixture with onions, is most popular for flavoring or thickening cooked rice and herbs. gumbo. File’ becomes stringy when boiled so should be added after the gumbo is finished Chickory (chick-ory) is an herb. -

LARRY AVERY French Market Foods—Lake Charles, LA

LARRY AVERY French Market Foods—Lake Charles, LA *** Date: September 10, 2007 Location: French Market Foods—Lake Charles, LA Interviewer: Sara Roahen Length: 39 minutes Project: Southern Boudin/Gumbo Trail 2 [Begin Larry Avery-Boudin/Gumbo Interview] 00:00:00 Sara Roahen: This is Sara Roahen with the Southern Foodways Alliance. It’s Monday, September 10, 2007. I’m in Lake Charles, Louisiana, at French Market Foods and I’m sitting here with Mr. Larry Avery. Could I get you to pronounce your first name yourself and tell me your birth date? 00:00:22 Larry Avery: Larry Avery, and my birthday is January 10, 1952. 00:00:26 SR: And what is your position here at French Market Foods? 00:00:31 LA: President and CEO. 00:00:32 SR: And how—what is your history with the company? How long have you been here? 00:00:38 © Southern Foodways Alliance www.southernfoodways.com 3 LA: Well I’m—I am the owner also, so we started the company in, back in 1999. We—by putting small food companies together, and now we’ve created a much larger food company. That was the basis for French Market Foods. 00:00:57 SR: And your—most of your product is sold under Tony Chachere’s? 00:01:05 LA: That’s correct. We did a licensing arrangement with Tony Chachere in 2003 where everything that we manufacture gets branded the Tony Chachere name. It’s worked very well for both companies. 00:01:20 SR: So—so I was pronouncing it wrong. -

715-543-8700 2020 Carry out Menu

2020 Carry Out Menu 715-543-8700 Website – www.AberdeenDining.com Appetizers Cheese Curds $8 Can’t break tradition-you gotta have ‘em! Wisconsin White Cheddar Curds served with Ranch Dressing Walleye Fingers $13 Canadian Walleye, hand battered & fried, served with Tartar Sauce & Lemon Soups & Salads Dressing Choices-Served on the side: French, Italian, Ranch, Blue Cheese, Sesame Vinaigrette Blackened Salmon Cobb* (GF) $19 Romaine, Cucumbers, Onions, Tomatoes, Bacon & Blue Cheese Crumbles. Topped with 6 oz. Blackened Salmon Filet Grilled Romaine Wedge $10 Artisan Romaine Wedge grilled & topped with Bacon, Tomato, Croutons & Blue Cheese Crumbles Crawfish Chowder $10 Traditional New England Style Chowder with Crawfish Desserts Peanut Butter Chocolate Silk Cake (GF) $9 Lori’s Bread Pudding $9 With homemade Whiskey Sauce Meals To Go Spanish Pork (GF) $19 Pork Tenderloin marinated & tenderized served over a bed of Spanish Rice topped with a Jalapeno Cream Sauce & fresh Pico de Gallo - Served with Seasonal Veggies Pasta Madeline $18 7 ounce Grilled Chicken Breast on a bed of Linguini layered with our popular Madeline Cream Sauce, accompanied by Sauteed Spinach & Prosciutto Canadian Walleye Fish Fry $18 Fried Canadian Walleye served with Aberdeen's homemade Tartar Sauce, Spicy Cole Slaw & Seasoned Waffle Fries Cheeseburger* $12 1/2 lb. Burger. Served with Lettuce, Tomato, Pickle & Onion. Topped with your choice of Cheddar, Pepper Jack or Provolone Cheese. Served with Seasoned Waffle Fries French Dip $16 Shaved Prime Rib marinated in Au Jus, layered