Mature Conviction: Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comisión Permanente Sobre Liturgia Y Música

COMISIÓN PERMANENTE SOBRE LITURGIA Y MÚSICA Integrantes Rev. Dra. Ruth Meyers, Presidenta, 2015 Rvmo. Steven Miller, Vicepresidente, 2015 Dr. Derek Olsen, Secretario, 2018 Rev. Dr. Paul Carmona, 2018 Rvmo. Rev. Thomas Ely, 2015 Sra. Ana Hernández, 2018 Sr. Drew Nathaniel Keane, 2018 Rvmo. Rev. John McKee Sloan, 2015 Sr. Beau Surratt, 2015 Rev. Dr. Louis Weil, 2015 Rev. Canon Sandye Wilson, 2018 Reverendísimo Dr. Brian Baker, Enlace del Consejo Ejecutivo, 2015 Rev. Canon Amy Chambers Cortright, Representante de la Cámara de Diputados, 2015 Rev. Canon Gregory Howe, Custodio del Libro de Oración Común, Ex Officio, 2015 Reverendísimo Dr. William H. Petersen, Consultor; Representante de Consultas sobre Textos Comunes Sr. Davis Perkins, Intermediario ante Church Publishing Incorporated Rev. Angela Ifill, personal del Centro Episcopal, 2015 Cambios en la membrecía El Sr. Dent Davidson renunció en abril de 2013 y no fue sustituido. El Sr. John Repulski, Vicepresidente, renunció en febrero de 2014 y fue sustituido por el Sr. Beau Surratt; El Rvmo. Steven Miller fue elegido Vicepresidente. Hno. Christopher Hamlett, OP, renunció en agosto de 2014 y no fue sustituido. El Rev. Chris Cunningham renunció al Consejo Ejecutivo y fue sustituido por el Reverendísimo Dr. Brian Baker en diciembre de 2013. El Sr. Davis Perkins sustituyó a la Sra. Nancy Bryan en la coordinación con Church Publishing Incorporated en octubre de 2013. Representación en la Convención General El Obispo Steven Miller y el Diputado Sandye Wilson tienen autorización para recibir enmiendas menores para este informe en la Convención General. Resumen de las actividades Mandato: El Canon I.1.2(n)(6) instruye a la Comisión Permanente sobre Liturgia y Música que haga lo siguiente: (i) Cumplir con las obligaciones que le sean asignadas por la Convención General en cuanto a políticas y estrategias relacionadas con el culto común de esta Iglesia. -

Days & Hours for Social Distance Walking Visitor Guidelines Lynden

53 22 D 4 21 8 48 9 38 NORTH 41 3 C 33 34 E 32 46 47 24 45 26 28 14 52 37 12 25 11 19 7 36 20 10 35 2 PARKING 40 39 50 6 5 51 15 17 27 1 44 13 30 18 G 29 16 43 23 PARKING F GARDEN 31 EXIT ENTRANCE BROWN DEER ROAD Lynden Sculpture Garden Visitor Guidelines NO CLIMBING ON SCULPTURE 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. Do not climb on the sculptures. They are works of art, just as you would find in an indoor art Milwaukee, WI 53217 museum, and are subject to the same issues of deterioration – and they endure the vagaries of our harsh climate. Many of the works have already spent nearly half a century outdoors 414-446-8794 and are quite fragile. Please be gentle with our art. LAKES & POND There is no wading, swimming or fishing allowed in the lakes or pond. Please do not throw For virtual tours of the anything into these bodies of water. VEGETATION & WILDLIFE sculpture collection and Please do not pick our flowers, fruits, or grasses, or climb the trees. We want every visitor to be able to enjoy the same views you have experienced. Protect our wildlife: do not feed, temporary installations, chase or touch fish, ducks, geese, frogs, turtles or other wildlife. visit: lynden.tours WEATHER All visitors must come inside immediately if there is any sign of lightning. PETS Pets are not allowed in the Lynden Sculpture Garden except on designated dog days. -

Transcultural Psychiatry

transcultural psychiatry December 2000 ARTICLE Stambali: Dissociative Possession and Trance in a Tunisian Healing Dance ELI SOMER University of Haifa and Israel Institute for Treatment and Study on Stress MEIR SAADON Israel Institute for Treatment and Study on Stress Abstract This study investigated Stambali, a Tunisian trance-dance prac- ticed in Israel as a healing and a demon exorcism ritual by Jewish-Tunisian immigrants. The authors observed the ritual and conducted semi-structured ethnographic interviews with key informants. Content analysis revealed that Stambali is practiced for prophylactic reasons (e.g. repelling the ‘evil eye’), for the promotion of personal well-being, and as a form of crisis inter- vention. Crisis was often construed by our informants as the punitive action of demons, and the ritual aimed at appeasing them. Communication with the possessing demons was facilitated through a kinetic trance induction, produced by an ascending tempo of rhythmic music and a corresponding increased speed of the participant’s movements of head and extremities. The experience was characterized by the emergence of dissociated eroticism and aggression, and terminated in a convulsive loss of consciousness. Stambali is discussed in terms of externalization and disowning of intrapsychic conflicts by oppressed women with few options for protest. Key words dance • demon possession • dissociative trance • Israel • Stambali • Tunisia Vol 37(4): 581–602[1363–4615(200012)37:4;581–602;014855] Copyright © 2000 McGill University Transcultural Psychiatry 37(4) A Judeo-African legend has it that Jews came to the Tunisian island of Djerba in King Solomon’s time. Archaeological findings and numerous texts prove the existence of Jewish communities in Tunisia during the first century CE. -

Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Fall 1977

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Alumni News Archives Fall 1977 Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Fall 1977 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Connecticut College Alumni Magazine, Fall 1977" (1977). Alumni News. 200. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/alumnews/200 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni News by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. The ggrnecticut Alu~ Mag::xzine ,.. Don • ., 1'1"" "f II,.. CJ'lI"Y" "I' NfEW!L.ONT>ON .. ." . " ~" • ,,' \ ., i\. I .\ \ •I " ',"<,- ~_ • Alb ; iiiiihh1WJihi •• ""h"'!h, .... EDITORIAL BOARD: AJlen T. Carroll'73 EdilOr(R.F.D. 3, Colches- President / Sally Lane Braman '54 Secretary / Platt Townend Arnold ter, Ct. 06415), Marion vilbert Clark '24 Class NOles Editor, Elizabeth '64 Treasurer . '56 Damerel Gongaware '26 Assistant Editor, Cassandra Goss Sitnonds '55, Directors-at-Large. Michael J. Farrar '73, Anne Godsey Sun nett , Louise Stevenson Andersen '41 ex officio Terry Munger '50, Gwendolyn Rendall Cross '62 / Alumni Trusl~e~ Official publication of the Connecticut College Alumni Association. All Virginia Golden Kent '35 Jane Smith Moody '49, Joan Jacobson Krome. publication rights reserved. Contents reprinted only by permission of the '46 / Chairman of A iumni Giving: Susan Lee '70 / Chairman of NOInI- editor. Published by the Connecticut College Alumni Association at Sykes noting ~ommittee: Joann Walton Leavenworth '56/ Chairman of Fm.a;~: Alumni Center, Connecticut College, New London, Conn. -

Moses Brown School Preferred Name *

;.. ‘‘ tates Department of the Interior :* _..ag’e Conservation and Recreation Service Q,HCRS -National Register of Historic Places dat. enterS Inventory-Nomination Form - See instructions In How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Friends’ Yearly Me eting School and/orcommon Moses Brown School preferred name * . 2. Location . street & number 250 Lloyd Avenue - not for publication city, town Providence - vicinity of congressional district112 Hon. Edward P. Beard state Rhode Islandeode 44 county Providence code 007 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use - district - public & occupied agriculture - museum ....._X buildings private unoccupied commercial - park structure both Iwork in progress .x. educational private residence - site Public Acquisition Accessible - entertainment - religious - object - In process ç yes: restricted - government - scientific being considered yes: unrest!icted - industrial - - transportation - no . military .. other: 4. Owner of Property name New England Yearly Meeting of Friends street&number The Maine Idyll U.S. Rte. 1 city, town R. D. 1, Freeport - vicinity of state Ma i tie 04032 5. Location of Legal Description . courthouse, registry ot deeds, etc. Providence City hail street & number 25 Dorrance Street Providence city, town state Rhode Island 02903 : 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Friends’ School, now Moses Brown School ;lfistorical American title Survey HABS #RI-255 has this property been determined eiegible? __yes date 1 963 .x_fede ral state county - local depository for survey records Rhode Island Historical Society Library ‘ city, town Providence state Rhode Tslarmd 02906 r’r’ 1: 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent _deteriorated .. unaltered JL original site _.2 good -. -

Tax Snag Predicted

55th Year No.9 GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY, WASHINGTON, D.C. Friday, November 1, 1974 Tax Snag Predicted Lawyer Cites Corp As Liability Threat by Joe Lacercnza University legal counsel has informed University officials of th« possibility that the Student Corporation may endanger the Universuy's tax-exempt status on the property which the Corporation occupies. The Board of Directors of Students of Georgetown, Inc. have contacted their lawyers at Arnold and Porter to investigate the situation. In a letter to Vice-President for Administrative Services. Daniel Altobello, Vincent J. Fuller of tho problem. Wt' art' confident Williams, Connolly, and Califano, that it canbe resolved," he noted. the University's counsel, expressed Altobello suggt'st('d a number the opinion that leasing space to of options in a memorandum to tho non-profit Student Corpora Vice-President for Student De ~tricia tion may make that space liable to velopment, Dr. Patricia Ruec kel , Dr. Rueckel real estate taxes. following receipt of the cortes might exclude the Corporation if "It is a serious legal question," pondence from University coun it i" considered a purdy corn Student Government President sel. "It seems to me Georgetown mercial establishment. Jack Leslie said. "The Board of can do one of several thing" ... A number of areas questioning Student Body President Jack Leslie expressed optimism that the Directors of the Corporation has i.itiate action to bring about th« the attorney's argument are bl'lng current controversy over the Corp's tax status will be resolved "in good agreed to negotiate with the appropiate pro-rata charging of studied. -

Prophets in Sixteenth Century French Literature by Jessica Singer A

Glimpsing the Divine: Prophets in Sixteenth Century French Literature By Jessica Singer A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Timothy Hampton, Chair Professor Déborah Blocker Professor Susan Maslan Professor Oliver Arnold Spring 2017 Abstract Glimpsing the Divine : Prophets in Sixteenth Century French Literature by Jessica Singer Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Timothy Hampton, Chair This project looks at literary representations of prophets from Rabelais to Montaigne. It discusses the centrality of the prophet to the construction of literary texts as well as the material conditions in which these modes of representation were developed. I analyze literature’s appropriation of Hebrew and Classical sources to establish its practices as both independent and politically relevant to the centralizing French monarchy. I propose that prophets are important to the construction of literary devices such as polyphonic discourse, the lyric subject, internal space, and first-person prose narration. The writers discussed in this project rely on the prophet to position their texts on the edge of larger socio-political and religious debates in order to provide a perceptive, critical voice. By participating in a language of enchantment, these writers weave between social and religious conceptualizations of prophets to propose new, specifically literary, roles for prophets. I look at François Rabelais’ prophetic genres – the almanac and the prognostication – in relation to his Tiers livre to discuss prophecy as a type of advice. I then turn to the work of the Pléiade coterie, beginning with Pierre de Ronsard, to argue for the centrality of the prophet to the formation of the lyric subject. -

Theories of Ritual

1 UNIT 6 COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGICAL I THEORIES OF RITUAL Structure I '. 6.0 Objectives 6.1 Introduction 6.2 What is a Ritual? 6.2.1 The Nature of Rituals 6.2.2 The Definitions of Rituals ' 6.3 Characteristics of Rituals. 6.3.1 Ritual Needs 6.3.2 Ritual as Conscious and Voluntary 6.3.3 Ritual as Repetitions and Stylized Bodily Actions 6.4 Types of Rituals 6.4.1 Confirmatory Rituals 6.4.2 Piacular Rituals 6.4.3 Other Types of Rituals 6.5 Theories of Ritual 6.5.1 Evolutionary Theories 6.5.2 Functionalist Theories 6.5.3 Fieldwork Investigations of Malinowski 6.5.4 Evans-Pritchard-The African Experience 6.5.5 Symbolic Dimension of Ritual 6.5.6 The Psychoanalytic Approach 6.6 The Importance of Rituals 6.7 Let Us Sum Up 6.8 Key Words 6.9 Further Readings 6.10 Answers to Check Your Progress 6.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit you should be able to : examine the phenomenon of ritual as it occurs both in the religion as well as everyday sphere, to understand what constitutes a ritual, especially as presented by sociologists and anthropologists, to appreciate the importance of ritual for those who participate in it as well as for the society. 6.1 INTRODUCTION In our earlier units, we asought to familiarize ourselves with certain sociological explanations in the field of religion. In this unit your attention and enquiry will be drawn to the various theories contributed by the sociologists for studying religious behaviour in the everyday life of a society. -

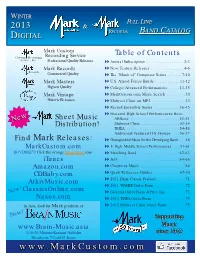

Digital Band Catalog V2 2012

WWINTERINTER FFULLULL LLINEINE 20132013 && RRECORDSECORDS BBANDAND CCATALOGATALOG DDIGITALIGITAL Mark Custom Table of Contents Custom Recording Recording Service Service, Inc. Professional Quality Releases Annual Subscription . 2-3 Mark Records New/Feature Releases . 4-6 Records Commercial Quality The “Music of” Composer Series . 7-10 Mark Masters U.S. Armed Forces Bands . 11-12 Highest Quality College/Advanced Performances . 13-35 Mark Vintage MarkCustom.com Music Search . 20 Historic Re-issues Midwest Clinic on MP3 . 32 Recital/Ensemble Series . 36-45 Featured High School Performances from: New Sheet Music All-State . 45-51 Distribution! Midwest Clinic . 51-54 TMEA . 54-56 Additional/Featured H.S. Groups . 56-57 Find Mark Releases: Distinguished Music for the Developing Band . 58 MarkCustom.com Jr. High/Middle School Performances . 57-61 BUY DIRECT! Click the orange Music Store icon. Marching Band . 62-63 iTunes Jazz . 64-66 Amazon.com Christmas Music . 66 CDBaby.com Quick Reference Guides . 67-70 ArkivMusic.com 2011 Dixie Classic Festival . 71 2011 WASBE Order Form . 72 New!ClassicsOnline.com General Order Form & Price List . 73 Naxos.com 2012 TMEA Order Form . 74 in Asia, look for Mark products at 2012 Midwest Clinic Order Form . 75 New! SupportingSupporting www.Brain-Music.asia MusicMusic 3-10-30 Minami-Kannon Nishi-ku sincesince 19621962 Hiroshima 733-0035 Japan www.MarkCustom.com Wind Band CD Subscription RECEIVE “Mark” CD Produced This Year! What is the “Mark CD Subscription?” The “Mark CD Subscription” includes CDs from conventions, universities, All-State recordings, Wind Band Festival CDs, and high quality high school projects. New Only $400 Reduced Price 13 CDs from The Midwest Clinic 2011 All Mark Masters & Mark Records University of Illinois David R. -

SEWARD JOHNSON Collection News: New GFS Beverly Pepper Explorers Guides WELCOME MEMBER EVENTS

FALL / WINTER 2020 REMEMBERING SEWARD JOHNSON Collection News: New GFS Beverly Pepper Explorers Guides WELCOME MEMBER EVENTS MEMBERS-ONLY HOURS ARTBOX Member Mornings have expanded! ArtBoxes are designed for children 5-12 years of age can be completed with Every Saturday and Sunday through November, members are granted exclusive family and friends at GFS, school, home or traveling. Each month will offer a early access to the grounds at 8 AM, and may stay as long as they wish. Enjoy new theme and supplies for you to explore. More info: a quiet start to your day and catch the morning light at GFS before the general public is admitted. At GFS, we believe visiting an oasis of beauty, where art and groundsforsculpture.org/artbox-6 imaginatively landscaped gardens awaken the senses, enhances well-being, and stimulates reflection. To ensure capacity is safely managed at GFS, Members and Guest Passes require a free reservation to visit. Reserve: groundsforsculpture.org/timed-admission-tickets MEMBERS' MUSINGS December 1, 2020 – February 28, 2021 An annual exhibition at Grounds For Sculpture, this year’s Members’ Musings is the eleventh show featuring artwork exclusively by GFS members. In addition Michael Unger, Gary Garrido Schneider, Seward Johnson and Eric Ryan to supporting the arts, many GFS members are gifted artists themselves. This Gary Garrido Schneider | Executive Director, Grounds For Sculpture exhibition showcases the diversity of the organization’s membership through their varied artistic creations and unique inspirations. This year’s exhibition will DIGITAL MEMBER LOUNGE On behalf of the staff and board of Grounds For Sculpture, I send warm isolated and living on Zoom meetings. -

The Golden Bough (Vol

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Golden Bough (Vol. 2 of 2) by James George Frazer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Golden Bough (Vol. 2 of 2) Author: James George Frazer Release Date: November 12, 2012 [Ebook 41359] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GOLDEN BOUGH (VOL. 2 OF 2)*** The Golden Bough A Study in Comparative Religion By James George Frazer, M.A. Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge In Two Volumes. Vol. II. New York and London MacMillan and Co. 1894 Contents Chapter III—(continued). .2 § 10.—The corn-spirit as an animal. .2 § 11.—Eating the god. 61 § 12.—Killing the divine animal. 81 § 13.—Transference of evil. 134 § 14.—Expulsion of evils, . 142 § 15.—Scapegoats. 165 § 16.—Killing the god in Mexico. 197 Chapter IV—The Golden Bough. 202 § 1.—Between heaven and earth. 202 § 2.—Balder. 220 § 3.—The external soul in folk-tales. 268 § 4.—The external soul in folk-custom. 295 § 5.—Conclusion. 323 Note. Offerings of first-fruits. 335 Index. 349 Footnotes . 443 [Transcriber's Note: The above cover image was produced by the submitter at Distributed Proofreaders, and is being placed into the public domain.] [001] Chapter III—(continued). § 10.—The corn-spirit as an animal. In some of the examples cited above to establish the meaning of the term “neck” as applied to the last sheaf, the corn-spirit appears in animal form as a gander, a goat, a hare, a cat, and a fox. -

A Perra Inexorável Se a Ethiopia (Or Invadida

¦' ——- UMA SECÇAO EDIÇÃO DE 14 PAGINAS y O JORNAL ANNO XVII MO DE JANEIRO — QUARTA-FEIRA, 7 DE AGOSTO DE 1935 S. 4.854 As providencias adoptadas pelo governo italiano fazem crer não haver mais duvida de que a guerra é inevitável Para regular a applica- A inexorável se a Ethiopia (Or invadida Graves oceorrencias nos dos decretos-leis perra estaleiros de Brest ção Tudo fará para manter a paz, mas em cas o de hostilidade agirá a altura da situação, Após um choque declarou ² entre os operários e as Convocada uma reunião, em Paris, de todos o imperador Hailé Selassié forças enviadas para combatel-os, aquelles — "COSSERIA" "Internacional" os prefeitos da França Os objectivos des- MANIFESTAÇÕES DE REGOSIJO, EM ROMA, PELA MOBILIZAÇÃO DA DIVISÃO se retiraram cantando a sa BREST, 6 (H.) — Verificarani-ao do francez ¦¦-;¦-v---r-*'.'v.¦¦•-'¦>. ¦y-y/.yy,:-:-.:-. pela manhã, no Amenal, providencia governo LONDRES, fi (Havas) — A im- .,.v.v—.syv........-*<.¦.'..*»....¦ ...,.• -..-.¦..¦,¦.•/.-..¦-¦'¦,%¦.-- >:-¦::•¦¦-¦¦ fvs'*:*.-•.¦¦;¦',••->.--.-x yy.y.--yyyy.".ymyy.T.-:y^,.-.-.- sra- ssssws&íí' ''[m:m::ym:ym/ ves incidentes; que tiveram inicio nos estaleiros onde so encontra o — prensa vespertina reproduz dechi- ¦/¦;•¦ ¦¦¦.¦ "Dunkerque", PARIS, 6 (Havas) Pela prinamra água, melhoramento do estradas, rações feitas iSiSiS¦¦¦¦¦•,-.-..•¦¦. .¦.-. .¦•¦.¦¦:¦ ?;,..;;/;••*;.;:-:¦•:-;.¦ -.¦•¦. .:mym cruzador-couracadci guardado pela tropa. vez foram convocados em Paris pelo Ncgus em Addis- Os operário» nüo to- quadruplicarão de vias férreas c ou- Abcba a um correspondento