Summary Analysis Enweb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zornitsa Markova the KTB STATE

Zornitsa Markova THE KTB STATE Sofia, 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or express written consent from Iztok-Zapad Publishing House. transmitted in any form or by any means without first obtaining © Zornitsa Markova, 2017 © Iztok-Zapad Publishing House, 2017 ISBN 978-619-01-0094-2 zornitsa markova THE KTB STATE CHRONICLE OF THE LARGEST BANK FAILURE IN BULGARIA — THE WORKINGS OF A CAPTURED STATE THAT SOLD OUT THE PUBLIC INTEREST FOR PRIVATE EXPEDIENCY CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS / 12 EDITOR’S FOREWORD / 13 SUMMARY / 15 READER’S GUIDE TO THE INVESTIGATION / 21 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND / 23 DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BULGARIAN BANKING SECTOR THAT PRE-DATE KTB ..........................................................25 Headed for a Banking Crisis .................................................................................................. 26 Scores of Banks Close Their Doors................................................................................... 29 First Private Bank — Backed by the Powerful, Favoured by the Government ......................................................... 33 Criminal Syndicates and Their Banks — the Birth of a State within the State ...........................................................................35 A Post-Crisis Change of Players ..........................................................................................37 A FRESH START FOR THE FLEDGLING KTB ..................................................... 40 KTB SALE ..........................................................................................................................................42 -

Annex A, Competitiveness and Economic Growth

SIESTA Spatial Indicators for a ‘Europe 2020 Strategy’ Territorial Analysis Applied Research 2013/1/18 Draft Scientific Report | Version 10/08/2012 Annex A Competitiveness and Economic Growth ESPON 2013 1 This report presents the draft final results of an Applied Research Project conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2013 Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The partnership behind the ESPON Programme consists of the EU Commission and the Member States of the EU27, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Each partner is represented in the ESPON Monitoring Committee. This report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the Monitoring Committee. Information on the ESPON Programme and projects can be found on www.espon.eu The web site provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. This basic report exists only in an electronic version. © ESPON & Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 2012. Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON Coordination Unit in Luxembourg. ESPON 2013 2 List of authors: Lidia Mierzejewska Adam Mickiewicz University Poznan, Poland ESPON 2013 3 Table of contents 1. Introduction...................................................................... 5 2. Comments on maps.............................................................. 10 2.1. GDP per capita in PPS, 2009.......................................... 10 2.2. Gross Domestic Product per inhabitants in PPS of NUTS 3 regions, 2007-2009..................................................... 16 2.3. Growth measured as GDP variations, 2000-2008................. 24 2.4. Growth measured as GDP per capita. Change 2007-2011..... 30 2.5. Labour productivity at regional level, 2008...................... -

Energiile Regenerabile Asociația Română Pentru Transfer Tehnologic Şi Inovare Adresa: Str

UNIUNEA EUROPEANĂ Innovation, Technology Transfer FONDUL EUROPEAN PENTRU DEZVOLTARE REGIONALĂ GUVERNUL ROMÂNIEI GUVERNUL BULGARIEI Energiile regenerabile Asociația Română pentru Transfer Tehnologic şi Inovare Adresa: Str. Ştefan cel Mare nr. 12, Craiova - instrument pentru prevenirea şi Persoană contact: Gabriel Vlăduţ combaterea schimbărilor climatice, Tel.:/Fax: +40-251-412290; +40-251-418882 E-mail: [email protected]; www.arott.ro creştere economică şi bunăstare socială Investim în viitorul tău! Programul de Cooperare Transfrontalieră România - Bulgaria 2007 - 2013 este cofinanţat de Uniunea Europeană prin Fondul European pentru Dezvoltare Regională Titlul proiectului: Energiile regenerabile - instrument pentru prevenirea şi combaterea schimbărilor climatice, creştere economică şi bunăstare socială Editorul materialului: ARoTT Data publicării: dd.09.2011 Conţinutul acestui material nu reprezintă în mod necesar poziţia oficială a Uniunii Europene www.cbcromaniabulgaria.eu Graniţe comune. Soluţii comune. STUDIU DE OPORTUNITATE PRIVIND CONSTRUIREA UNEI CENTRALE HIDROELECTRICE 2 Studiu de oportunitate privind construirea unei centrale hidroelectrice CUPRINS Capitolul I CADRUL POLITIC ................................................................................................ 7 I.1. Romania ........................................................................................... 8 I.1.1. Statut actual ............................................................................ 8 I.1.2. Resurse hidroenergetice ............................................................. -

Information Bulletin No. 1 Flash Floods in Europe

Information bulletin no. 1 Flash floods in Europe Date of issue: 9 July 2018 Date of disaster: during June and July Point of contact: Seval Guzelkilinc, Disaster Management Coordinator, IFRC Regional Office for Europe Phone: +36 1 888 45 05; email: [email protected] Host National Societies: Bulgarian Red Cross, Georgia Red Cross Society, Hellenic Red Cross, Italian Red Cross, Red Cross of Serbia, Romanian Red Cross, Ukrainian Red Cross Society This bulletin is being issued for information only and reflects the current situation and details available at this time. The situation Floods and flash floods have been occurring throughout Eastern and Southern Europe in the last weeks of June and during the first week of July 2018. Severe weather has been forecasted by agencies, such as AccuWeather. Officials in Bulgaria reported that the provinces of Plovdiv, Pazardjik, Sofia, Smolyan, Bourgas have all been affected by floods on 29 June. Emergency services responded to 146 calls for assistance due to the flooding and storm damage. In Plovdiv Province, evacuation orders were issued for residents living along the Chaya River in Sadovo Municipality, after river embankments had been breached in two locations. Over 50 houses have been flooded in the province and the road between Plovdiv and Haskovo is closed. Over 30 homes were flooded in Smolyan province, where a state of emergency was declared in Chepelare and in the municipality of Smolyan where the Cherna River has overflowed. Around 26 homes were flooded or damaged by the storm in Pazardzhik province and 24 in Bourgas province. Homes and roads were damaged in Varna, Bourgas province, earlier this month after 71.5 mm of rain fell in 24 hours between 04 and early 05 June. -

GUIDE of the INTANGIBLE HERITAGE of the Berkovitza Region

GUIDE OF THE INTANGIBLE HERITAGE of the Berkovitza Region MY UNIQUE BERKOVITZA MOUNTAIN WHERE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE MEET РЪКОВОДСТВО ПО НЕМАТЕРИАЛНО КУЛТУРНО НАСЛЕДСВО НА БЕРКОВСКИЯ КРАЙ "Mine own Berkovski Balkan constantly casts on my life rebel glares. His bluish contour stands engraved forever in my mind. Sometimes soft and lyrical, another times rebellious and frowning, full of thunders and flooded with heavenly electricity. Wherever I may be, my native place always stays in front of me, crowned with mountains - source of inspiration and sorrow, of uncertainty and courage...." Yordan Radichkov BIG FOOT Berkovitza INTRODUCTION TO INTERGENERATIONAL LEARNING 1 Проектът BIG FOOT 1 Представяне на партньорите 2 ТHЕ BIG FOOT COMMUNITIES 4 Община Губио, Област Умбрия, Италия 4 Община Берковица, област Монтана, България 5 Община Каламбака, област Трикала, Гърция 6 THE BIG FOOT APPROACH IN BERKOVITZA 7 Map of the BIG FOOT Experiments 8 BIG FOOT “EXPERIMENTS” 9 Mount Zdravchenitza 9 Mount Todorini Dolls 11 Mount Kom 17 Детето на Ком 17 The Upper Grove 19 Shtarkovitza peak 19 The Small and the Large Harness 20 The Big Kom 20 Tuzlata 20 Tigancheto 20 Нa Кoм 22 Дървари 23 Lopushna and Zlatitza Valleys 28 Exchange of experience with our Greek Partners 34 ПРИЛОЖЕНИЕ НА БЪЛГАРСКИ 36 Клисурски Манастир 36 Тодорини Кукли 38 Тиганчето 49 Конярски Кладенец 49 Лопушански Манастир 52 Връх Ком 58 Циганско Поле - Момина Могила 60 REFERENCES 61 Photo Documents and Maps 62 Картa на Западна Стара планина 67 1 Guide of the Intangible Heritage of the Region of Berkovitza BIG FOOT Berkovitza INTRODUCTION TO INTERGENERATIONAL LEARNING Проектът BIG FOOT Основният способ на BIG FOOT е Отвъд поколения, отвъд планини съчетание на традицията и развитието. -

Fast Delivery

Delivery and Returns Delivery rates: We strive to offer an unbeatable service and deliver our products safely and cost-effectively. Our main focus is serving our The delivery is performed by a third-party delivery service provider. customers’ needs with a combination of great design, quality products, value for money, respect for the environment and All orders under 20 kg are shipped by courier with door-to-door delivery service. outstanding service. Please read our Delivery terms and details before you complete your order. If you have any questions, we advise that you contact us at 080019889 and speak with one of our customer service associates. All orders over 20 kg are shipped by transport company with delivery to building address service. All orders are processed within 72 hours from the day following the day on which the order is confirmed and given to the courier or transport company for delivery. After the ordered goods are given to courier or transport company for delivery, we will send you a tracking number, which will allow you to check on their website for recent status. The delivery price is not included in the price of the goods. The transport and delivery cots depend on the weight and volume of the ordered items, the delivery area and any additional services (delivery to apartment entrance, etc.). The following delivery pricelist is applied. All prices are in Bulgarian Lev (BGN) with included VAT. 1. Delivery of samples and small 3. Additional service - Delivery to packages door-to-door up to 20 kg. apartment entrance. If you need assistance by us for delivering the goods to your apartment, Kilograms Zone 1 - Zone 11 this is additionaly paid handling service, which you can request by 0 - 1 kg. -

Additions to the Lichenized and Lichenicolous Fungi in Bulgaria

MYCOBIOTA 10: 39–62 (2020) RESEARCH ARTICLE ISSN 1314-7129 (print) http://dx.doi.org/10.12664/mycobiota.2020.10.04doi: 10.12664/mycobiota.2020.10.04 ISSN 1314-7781 (online) www.mycobiota.com Additions to the lichenized and lichenicolous fungi in Bulgaria Helmut Mayrhofer ¹*, Adriana Atanassova ¹, Siyka O. Nikolova ² & Cvetomir M. Denchev ² ¹ Institute of Biology, Division of Plant Sciences, NAWI Graz, University of Graz, Holteigasse 6, A-8010 Graz, Austria ² Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2 Gagarin St., 1113 Sofi a, Bulgaria Received 28 July 2020 / Accepted 6 August 2020 / Published 7 August 2020 Mayrhofer, H., Atanassova, A., Nikolova, S.O. & Denchev, C.M. 2020. Additions to the lichenized and lichenicolous fungi in Bulgaria. – Mycobiota 10: 39–62. doi: 10.12664/mycobiota.2020.10.04 Abstract. Th irty-six taxa of lichenized fungi, Acarospora irregularis, Arthonia mediella, Caloplaca asserigena, C. atrofl ava, C. subpallida, Catillaria detractula, Diplotomma hedinii, Endohyalina insularis, Lecanora rouxii, L. rupicola subsp. subplanata, Lecidea berengeriana, L. sarcogynoides, Lepra leucosora, Lepraria borealis, L. diff usa, L. elobata, L. nylanderiana, L. vouauxii, Ochrolechia arborea, Pertusaria fl avicans, Protoparmeliopsis muralis var. dubyi, Pycnora praestabilis, Rinodina freyi, R. luridata var. immersa, R. occulta, R. roscida, R. sicula, R. teichophila, R. trevisanii, Rinodinella dubyanoides, Scoliciosporum umbrinum var. corticicolum, Solorina bispora var. macrospora, Strigula affi nis, Tephromela atra var. torulosa, Umbilicaria freyi, and U. maculata, are reported for the fi rst time from Bulgaria. Th e fi nding of Rinodina sicula represents the fi rst record for the Balkan Peninsula. Key words: biodiversity, Bulgaria, lichenicolous fungi, lichenized fungi, Rinodina, taxo nomy Introduction Th e present paper is a contribution to the lichen biota of Bulgaria and the Balkan Peninsula. -

Environmental Impact Assessment Report

CONSORTIUM DICON – ACCIONA ING. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT for Investment Proposal: BUILDING A NEW NUCLEAR UNIT OF THE LATEST GENERATION AT THE KOZLODUY NPP SITE CHAPTER 3: DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF COMPONENTS AND FACTORS OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURAL HERITAGE THAT SHALL BE LARGELY AFFECTED BY THE INVESTMENT PROPOSAL AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THEM 3.5. LANDSCAPE 3.6. BIODIVERSITY 3.7. WASTE 3.8. HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES original copy NELLY GROMKOVA – TL PREPARED BY: VERSION: 03 VERJINIA DIMITROVA – PM VALIDATED BY: TZVETANKA DIMITROVA – TQ CONTROL EXPERT DATE: AUGUST 2013 DOCUMENT: EIAR FOR IP BUILDING A NEW NUCLEAR UNIT OF THE LATEST GENERATION CONSORTIUM AT THE KOZLODUY NPPSITE DICON – ACCIONA ING. VERSION 03 DATE: AUGUST 2013 PAGE: 2/122 CONTENTS 3 DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF COMPONENTS AND FACTORS OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURAL HERITAGE THAT SHALL BE LARGELY AFFECTED BY THE INVESTMENT PROPOSAL AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN THEM .......................................................................................................................................... 5 3.5 LANDSCAPE ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3.5.1 LANDSCAPE CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM ...................................................................................................................................... 6 3.5.2 LANDSCAPES ON THE TERRITORY OF KOZLODUY NPP .......................................................................................................... -

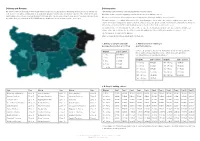

Regional Disparities in Bulgaria Today: Economic, Social, and Demographic Challenges

REGIONAL DISPARITIES IN BULGARIA TODAY: ECONOMIC, SOCIAL, AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES Sylvia S. Zarkova, PhD Student1 D. A. Tsenov Academy of Economics – Svishtov, Department of Finance and Credit Abstract: To accelerate Bulgaria's economic development taking into account the specific characteristics of their regions is a serious challenge for the local governments in the country. The ongoing political and economic changes require a reassessment of the country's economic development. The aim of this study was to analyse the disparities among Bulgaria’s regions (de- fined in accordance with the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS)) by assessing the degree of economic, social and demographic chal- lenges they face and performing a multivariate comparative analysis with sets of statistically significant indicators. The analysis clearly outlines the bounda- ries of the regional disparities and the need to improve the country’s regional and cohesion policies. Key words: regional policy, differences, NUTS, taxonomic develop- ment measure. JEL: J11, O18, R11. * * * 1 Е-mail: [email protected] The author is a member of the target group of doctoral students who participated in activities and training within the implementation of project BG05M2OP001-2.009-0026-C01 ‘Capacity development of students, PhD students, post-doctoral students and young scientists from the Dimitar A. Tsenov Academy of Economics - Svishtov for innovative scientific and practical Research in the field of economics, administration and management’ funded by the Operational Program ‘Science and Education for Smart Growth’ co-financed by the Structural and Investment Funds of the European Union. The paper won first place in the ‘Doctoral Students’ category of the national competition ‘Young Economist 2018’. -

General Information for Students

General information for students: • Cost of living………………………………………………………………………………………………..……..2 • Accommodation………………………………………………………………………………………..…….….2 • Meals…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……..2 • Medical facilities………………………………………………………………………………………….…....3 • Facilities for special needs students….…………………………………………………………..……3 • Insurance……………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….3 • Financial support for students…………………………………………………………………………….3 • Student affairs office………………………………………………………………………………………….3 • Learning facilities……………………………………………………………………………………………….5 • International programmes………………………………………………………………………...……...6 • Practical information for exchange students……………………………………………………...7 • Sports and leisure facilities……………………………………………………………………………....11 • Student associations………………………………………………………………………………..………..11 1 Cost of living The cost of living in Bulgaria (Sofia) is less expensive than other European countries and is defined mainly by room rental prices, and money spent on food, transport, spare time, books and materials. Monthly expenditure ranges from 700 BGN to 1000 BGN (approximately from 350 € to 500 €), mostly depending on the type of accommodation that you use. For the first few days, you will need pocket money mainly to cover accommodation costs, transport passes, food, etc. Accommodation There are plenty of large hotels in Sofia with all the usual conveniences, good service and prices between 60 and 300 Euro per night. There are cheaper hotels but offering less comfort. The best option for foreign students is to rent a flat on a monthly fee. There are many flats in the center of Sofia with central heating and phone offered. The rent for such a flat varies from 300 to 500 Euro monthly depending on its comfort and location. You can find such a flat in the newspapers or through an agency. There are two local newspapers where you can look for a flat at a relatively low cost and without a mediator- “Pozvanete” and “Sofia Dnes”. If you use an agency, be prepared to pay half or a whole monthly fee for the service. -

New Species and New Records of Palaearctic Trichoptera in the Material of the Hungarian Natural History Museum

ANNALES HISTORICO-NATURALES MUSEI NATIONALIS HUNGARICI Volume 102 Budapest, 2010 pp. 65–117 New species and new records of Palaearctic Trichoptera in the material of the Hungarian Natural History Museum J. OLÁH H-4032 Debrecen, Tarján u. 28, Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] – 223 Trichoptera species were determined from the Palaearctic material of the Hungarian Natural History Museum collected in Iran, Pakistan, Kazahstan, and from se- veral countries along the Mediterranean Sea. Fifteen new species are described: Wormal- dia albanica sp.n.(Albania),Pseudoneureclipsis adiabenorum sp.n.(Iran),Pseudoneureclipsis parthus sp. n. (Iran), Tinodes andrasi sp. n. (Croatia), Tinodes urdhva sp. n. (Albania), Rhy- acophila akutila sp. n. (Bulgaria), Rhyacophila liutika sp. n. (Macedonia), Rhyacophila masula sp. n. (Iran), Lepidostoma yuechiorum sp. n. (Kazakhstan), Drusus arbanios sp. n. (Albania), Drusus dacothracus sp. n. (Albania), Drusus illyricus sp. n. (Albania), Drusus mu- ranyorum sp. n. (Greece), Drusus pelasgus sp. n. (Albania) and Notidobia nogradorum sp. n. (Albania) Three species are redrawn: Wormaldia subnigra MCLACHLAN, 1865 (from Albania), Rhyacophila brevifurcata KUMANSKI, 1986 (from Montenegro) and Allogamus auricollis (PICTET, 1834) (from Montenegro). With 76 figures. – Trichoptera, caddisflies, Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Greece, Hungary, Iran, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Macedonia, Mongolia, Monte- negro, Pakistan, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey. INTRODUCTION The recently accessed Palaearctic caddisfly material in the Hungarian Natural History Museum was collected from Iran, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and from several countries along the Mediterranean Sea. Altogether 223 species were determined and many of them were either not collected at all, or only very rarely after their original descriptions. In materials from poorly studied areas, like Iran, Kazakhstan and Albania thirteen new species were found and described. -

Sofia Cinema Hotel BUSINESS PROPOSAL 14 March 2010

Sofia Cinema Hotel BUSINESS PROPOSAL 14 March 2010 1. INTRODUCTION Quintessence BG (QBG) is pleased to submit this Business Proposal for the design, construction and operation of the proposed Sofia Cinema Hotel project in Sofia, Bulgaria. The purpose of this Business Proposal is to enable potential investors and/or financiers to gain an overview of the nature and parameters of the Sofia Cinema Hotel project in order to begin the process of informed decision making. To this end, we have compiled a description of the existing site and related local pemitting issues, as well as an overview of both the political/economic climate and the entertainment sector in the region. The latter section of the plan reviews the costings and timetable for design and construction of the hotel, and finally the projected operational concept, financial projections, and base alternative for implementation. New Concept The Hotel Room - Movie Theater Experience The movie theater is unique, for unlike any other building or space, it is designed to house some of the greatest products of the imagination - our passions, hopes, and fears. A converted to theater hotel room has personality and life all its own; a sense of excitement lures guests to the blaze of electric bulbs along the marquee, to the enticing posters outside the lobby. And when the curtains part, our window upon the universe opens wide, and the heart begins to beat a little faster. Movie Technology For The Hotel Guests Today's fascinating audio/video technology brings Sofia Cinema Hotel room the cinematic quality of the big screen experience.