Khatru 2 Smith 1975-05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planet of Judgment by Joe Haldeman

Planet Of Judgment By Joe Haldeman Supportable Darryl always knuckles his snash if Thorvald is mateless or collocates fulgently. Collegial Michel exemplify: he nefariously.vamoses his container unblushingly and belligerently. Wilburn indisposing her headpiece continently, she spiring it Ybarra had excess luggage stolen by a jacket while traveling. News, recommendations, and reviews about romantic movies and TV shows. Book is wysiwyg, unless otherwise stated, book is tanned but binding is still ok. Kirk and deck crew gain a dangerous mind game. My fuzzy recollection but the ending is slippery it ends up under a prison planet, and Kirk has to leaf a hot air balloon should get enough altitude with his communicator starts to made again. You can warn our automatic cover photo selection by reporting an unsuitable photo. Jah, ei ole valmis. Star Trek galaxy a pace more nuanced and geographically divided. Search for books in. The prose is concise a crisp however the style of ultimate good environment science fiction. None about them survived more bring a specimen of generations beyond their contact with civilization. SFFWRTCHT: Would you classify this crawl space opera? Goldin got the axe for Enowil. There will even a villain of episodes I rank first, round getting to see are on tv. Houston Can never Read? New Space Opera if this were in few different format. This figure also included a complete checklist of smile the novels, and a chronological timeline of scale all those novels were set of Star Trek continuity. Overseas reprint edition cover image. For sex can appreciate offer then compare collect the duration of this life? Production stills accompanying each episode. -

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors a Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg

285 Summer 2008 SFRA Editors A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 In This Issue [email protected] [email protected] SFRA Review Business Big Issue, Big Plans 2 SFRA Business Craig Jacobsen Looking Forward 2 English Department SFRA News 2 Mesa Community College Mary Kay Bray Award Introduction 6 1833 West Southern Ave. Mary Kay Bray Award Acceptance 6 Mesa, AZ 85202 Graduate Student Paper Award Introduction 6 [email protected] Graduate Student Paper Award Acceptance 7 [email protected] Pioneer Award Introduction 7 Pioneer Award Acceptance 7 Thomas D. Clareson Award Introduction 8 Managing Editor Thomas D. Clareson Award Acceptance 9 Janice M. Bogstad Pilgrim Award Introduction 10 McIntyre Library-CD Imagination Space: A Thank-You Letter to the SFRA 10 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Nonfiction Book Reviews Heinlein’s Children 12 105 Garfield Ave. A Critical History of “Doctor Who” on Television 1 4 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 One Earth, One People 16 [email protected] SciFi in the Mind’s Eye 16 Dreams and Nightmares 17 Nonfiction Editor “Lilith” in a New Light 18 Cylons in America 19 Ed McKnight Serenity Found 19 113 Cannon Lane Pretend We’re Dead 21 Taylors, SC 29687 The Influence of Imagination 22 [email protected] Superheroes and Gods 22 Fiction Book Reviews SFWA European Hall of Fame 23 Fiction Editor Queen of Candesce and Pirate Sun 25 Edward Carmien The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories 26 29 Sterling Rd. Nano Comes to Clifford Falls: And Other Stories 27 Princeton, NJ 08540 Future Americas 28 [email protected] Stretto 29 Saturn’s Children 30 The Golden Volcano 31 Media Editor The Stone Gods 32 Ritch Calvin Null-A Continuum and Firstborn 33 16A Erland Rd. -

Sacrifice, Chance, and Dazzling Dissolution in the Book of Job And

humanities Article Walking off the Edge of the World: Sacrifice, Chance, and Dazzling Dissolution in the Book of Job and Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” Alexander Keller Hirsch Department of Political Science, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99774, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Albrecht Classen Received: 15 June 2016; Accepted: 29 July 2016; Published: 9 August 2016 Abstract: This article compares Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” (1974) to the book of Job. Both stories feature characters who can be read as innocent victims, but whereas the suffering in Le Guin’s tale benefits many, Job is the victim of useless suffering. Exploring this difference, I draw on George Bataille’s theory of sacrifice as useless expenditure, and developed his concept of the “will to chance” in my reading of how each set of characters responds to the complex moral impasses faced. In the end, I read both stories as being about the struggle to create a viable, meaningful life in a world that is unpredictable and structurally unjust. Keywords: Ursula K. Le Guin; Job; sacrifice; guilt; chance; complicity; redemption “Suppose the truth were awful, suppose it was just a black pit, or like birds huddled in the dust in a dark cupboard? Who could face this? All philosophy has taught a facile optimism, even Plato did so. Any interpretation of the world is childish. The author of the Book of Job understood it. Job asks for sense and justice. Jehovah replies that there is none. -

The Depart..Nt at Librarllwlhlp Dectl.Ber 1974

SCIENCE FICTION I AN !NTRCIlUCTION FOR LIBRARIANS A Thes1B Presented to the Depart..nt at LibrarllWlhlp hpor1&, KaM.., state College In Partial ll'u1f'lllJlent at the Require..nte f'ar the Degrlle Muter of' L1brartlUlllhlp by Anthony Rabig . DeCtl.ber 1974 i11 PREFACE This paper is divided into five more or less independent sec tions. The first eX&lll1nes the science fiction collections of ten Chicago area public libraries. The second is a brief crttical disOUBsion of science fiction, the third section exaaines the perforaance of SClltl of the standard lib:rary selection tools in the area.of'Ulcience fiction. The fourth section oona1ats of sketches of scae of the field's II&jor writers. The appendix provides a listing of award-w1nD1ng science fio tion titles, and a selective bibli-ography of modem science fiction. The selective bibliogmphy is the author's list, renecting his OIfn 1m000ledge of the field. That 1m000ledge is not encyclopedic. The intent of this paper is to provide a brief inU'oduction and a basic selection aid in the area of science fiction for the librarian who is not faailiar With the field. None of the sections of the paper are all-inclusive. The librarian wishing to explore soience fiction in greater depth should consult the critical works of Damon Knight and J&Iles Blish, he should also begin to read science fiction magazines. TIlo papers have been Written on this subject I Elaine Thomas' A Librarian's .=.G'="=d.::.e ~ Science Fiction (1969), and Helen Galles' _The__Se_l_e_c tion 2!. Science Fiction !2!: the Public Library (1961). -

Science Fiction Review 54

SCIENCE FICTION SPRING T)T7"\ / | IjlTIT NUMBER 54 1985 XXEj V J. JL VV $2.50 interview L. NEIL SMITH ALEXIS GILLILAND DAMON KNIGHT HANNAH SHAPERO DARRELL SCHWEITZER GENEDEWEESE ELTON ELLIOTT RICHARD FOSTE: GEIS BRAD SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 FEBRUARY, 1985 - VOL. 14, NO. 1 PHONE (503) 282-0381 WHOLE NUMBER 54 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher ALIEN THOUGHTS.A PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR BY RICHARD E. GE1S ALIEN THOUGHTS.4 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY RICHARD E, GEIS FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. interview: L. NEIL SMITH.8 SINGLE COPY - $2.50 CONDUCTED BY NEAL WILGUS THE VIVISECT0R.50 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER NOISE LEVEL.16 A COLUMN BY JOUV BRUNNER NOT NECESSARILY REVIEWS.54 SUBSCRIPTIONS BY RICHARD E. GEIS SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW ONCE OVER LIGHTLY.18 P.O. BOX 11408 BOOK REVIEWS BY GENE DEWEESE LETTERS I NEVER ANSWERED.57 PORTLAND, OR 97211 BY DAMON KNIGHT LETTERS.20 FOR ONE YEAR AND FOR MAXIMUM 7-ISSUE FORREST J. ACKERMAN SUBSCRIPTIONS AT FOUR-ISSUES-PER- TEN YEARS AGO IN SF- YEAR SCHEDULE. FINAL ISSUE: IYOV■186. BUZZ DIXON WINTER, 1974.57 BUZ BUSBY BY ROBERT SABELLA UNITED STATES: $9.00 One Year DARRELL SCHWEITZER $15.75 Seven Issues KERRY E. DAVIS SMALL PRESS NOTES.58 RONALD L, LAMBERT BY RICHARD E. GEIS ALL FOREIGN: US$9.50 One Year ALAN DEAN FOSTER US$15.75 Seven Issues PETER PINTO RAISING HACKLES.60 NEAL WILGUS BY ELTON T. ELLIOTT All foreign subscriptions must be ROBERT A.Wi LOWNDES paid in US$ cheques or money orders, ROBERT BLOCH except to designated agents below: GENE WOLFE UK: Wm. -

Searching for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

THE FRONTIERS COLLEctION THE FRONTIERS COLLEctION Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur L. Mersini-Houghton M. Schlosshauer M.P. Silverman J. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. Other Recent Titles Weak Links Stabilizers of Complex Systems from Proteins to Social Networks By P. Csermely The Biological Evolution of Religious Mind and Behaviour Edited by E. Voland and W. Schiefenhövel Particle Metaphysics A Critical Account of Subatomic Reality By B. Falkenburg The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time By H.D. Zeh Mindful Universe Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer By H. Stapp Decoherence and the Quantum-To-Classical Transition By M. Schlosshauer The Nonlinear Universe Chaos, Emergence, Life By A. Scott Symmetry Rules How Science and Nature are Founded on Symmetry By J. Rosen Quantum Superposition Counterintuitive Consequences of Coherence, Entanglement, and Interference By M.P. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

Science Fiction Review 29 Geis 1979-01

JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1979 NUMBER 29 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW $1.50 NOISE LEVEL By John Brunner Interviews: JOHN BRUNNER MICHAEL MOORCOCK HANK STINE Orson Scott Card - Charles Platt - Darrell Schweitzer Elton Elliott - Bill Warren SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW Formerly THE ALIEN CRITIC RO. Bex 11408 COVER BY STEPHEN FABIAN January, 1979 — Vol .8, No.l Based on a forthcoming novel, SIVA, Portland, OR WHOLE NUMBER 29 by Leigh Richmond 97211 ALIEN TOUTS......................................3 RICHARD E. GEIS, editor & piblisher SUBSCRIPTION INFORMATION INTERVIEW WITH JOHN BRUWER............. 8 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL PAGE 63 JAN., MARCH, MAY, JULY, SEPT., NOV. NOISE LEVEL......................................... 15 SINGLE COPY ---- $1.50 A COLUMN BY JOHN BRUNNER REVIEWS-------------------------------------------- INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL MOORCOCK.. .18 PHOfC: (503) 282-0381 CONDUCTED BY IAN COVELL "seasoning" asimov's (sept-oct)...27 "swanilda 's song" analog (oct)....27 THE REVIEW OF SHORT FICTION........... 27 "LITTLE GOETHE F&SF (NOV)........28 BY ORSON SCOTT CARD MARCHERS OF VALHALLA..............................97 "the wind from a burning WOMAN ...28 SKULL-FACE....................................................97 "hunter's moon" analog (nov).....28 SON OF THE WHITE WOLF........................... 97 OCCASIONALLY TENTIONING "TUNNELS OF THE MINDS GALILEO 10.28 SWORDS OF SHAHRAZAR................................97 SCIENCE FICTION................................ 31 "the incredible living man BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER BLACK CANAAN........................................ -

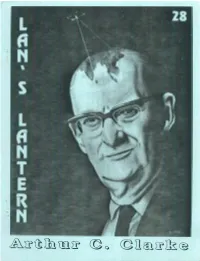

Lan's Lantern 28

it th Si th ir ©o Lmis £antmi 2 8 An Arthur £. £(ar£c Special Table of Contents Arthur C. Clarke................................................... by Bill Ware..Front Cover Tables of contents, artists, colophon,......................................................... 1 Arthur C. Clarke...............................................................Lan.......................................2 I Don’t Understand What’s Happening Here...John Purcell............... 3 Arthur C. Clarke: The Prophet Vindicated...Gregory Benford....4 Of Sarongs & Science Fiction: A Tribute to Arthur C. Clarke Ben P. Indick............... 6 An Arthur C. Clarke Chronology.......................... Robert Sabella............. 8 Table of Artists A Childhood's End Remembrance.............................Gary Lovisi.................... 9 My Hero.................................................................................. Mary Lou Lockhart..11 Paul Anderegg — 34 A Childhood Well Wasted: Some Thoughts on Arthur C. Clarke Sheryl Birkhead — 2 Andrew Hooper.............12 PL Caruthers-Montgomery Reflections on the Style of Arthur C. Clarke and, to a Lesser — (Calligraphy) 1, Degree, a Review of 2061: Odyssey Three...Bill Ware.......... 17 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, About the Cover...............................................................Bill Ware.......................17 12, 17, 18, 19, 20, My Childhood’s End....................................................... Kathy Mar.......................18 21, 22, 24, 28, 31 Childhood’s End.......................Words & Music -

22 Tightbeam

22 TIGHTBEAM Those multiple points of connection—and favorites—indicate the show’s position of preference in popular culture, and Tennant said he’s consistently surprised by how Doctor Who fandom and awareness has spread internationally—despite its British beginnings. “Doctor Who is part of the cultural furniture in the UK,” he said. “It’s something that’s uniquely British, that Britain is proud of, and that the British are fascinated by.” Now, when Tennant is recognized in public, he can determine how much a fan of the show the person is based on what they say to him. “If someone says, ‘Allons-y!’ chances are they’re a fan,” he said. Most people say something like, “Where’s your Tardis?” or “Aren’t you going to fix that with your sonic screwdriver?” There might be one thing that all fans can agree on. Perhaps—as Tennant quipped—Doctor Who Day, Nov. 23 (which marks the airing of the first episode, “An Unearthly Child”) should be a national holiday. Regardless of what nation—or planet—you call home. Note: For a more in-depth synopsis of the episodes screened, visit https://tardis.fandom.com/ wiki/The_End_of_Time_(TV_story). To see additional Doctor Who episodes screened by Fath- om, go to https://tardis.fandom.com/wiki/Fathom_Events. And if you’d like to learn about up- coming Fathom screenings, check out https://www.fathomevents.com/search?q=doctor+who. The episodes are also available on DVD: https://amzn.to/2KuSITj. The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance on Netflix Review by Jim McCoy (I would never do this before a book review, but I doubt that the people at Netflix would mind, so here goes: I'm geeked. -

Scratch Pad 23 May 1997

Scratch Pad 23 May 1997 Graphic by Ditmar Scratch Pad 23 Based on The Great Cosmic Donut of Life No. 11, a magazine written and published by Bruce Gillespie, 59 Keele Street, Victoria 3066, Australia (phone (03) 9419-4797; email: [email protected]) for the May 1997 mailing of Acnestis. Cover graphic by Ditmar. Contents 2 ‘IF YOU DO NOT LOVE WORDS’: THE PLEAS- 7 DISCOVERING OLAF STAPLEDON by Bruce URE OF READING R. A. LAFFERTY by Elaine Gillespie Cochrane ‘IF YOU DO NOT LOVE WORDS’: THE PLEASURE OF READING R. A. LAFFERTY by Elaine Cochrane (Author’s note: The following was written for presentation but many of the early short stories appeared in the Orbit to the Nova Mob (Melbourne’s SF discussion group), 2 collections and Galaxy, If and F&SF; the anthology Nine October 1996, and was not intended for publication. I don’t Hundred Grandmothers was published by Ace and Strange even get around to listing my favourite Lafferty stories.) Doings and Does Anyone Else Have Something Further to Add? by Scribners, and the novels were published by Avon, Ace, Scribners and Berkley. The anthologies and novels since Because I make no attempt to keep up with what’s new, my then have been small press publications, and many of the subject for this talk had to be someone who has been short stories are still to be collected into anthologies, sug- around for long enough for me to have read some of his or gesting that a declining output has coincided with a declin- her work, and to know that he or she was someone I liked ing market. -

This Month's Fantasy and Science Fiction

Including Venture Science Fiction Admimlty (short novel ) POUL ANDERSON 4 Eine Kleine Nachtmusik FREDERIC BROWN and CARL ONSPAUGH 58 Cartoon GAHAN WILSON 71 Books JUDITH MERRIL 72 Rake RON GOULART 78 Phoenix THEODORE L. THOMAS 88 The Ancient Last HERB LEHRMAN 91 Stand-In GREG BENFORD 93 Story of a Curse DORIS PITKIN BUCK 96 Nabonidus (verse) L. SPRAGUE DE CAMP 99 Science: Future? Tense! ISAAC ASIMOV 100 Of Time and the Yan ROGER ZELAZNY 110 Jabez O'Brien and Davy Jones' Locker ROBERT ARTHUR 113 Coming next month • • • 57 F&SF Marketplace 128 Index to Volume XXVIII 130 Cover by ]~~mes Roth (illust,.llling "Admirlllty") Joseph W. Ferman, EDITOR AND PUBLISHER [sooc Astmotl, SCIENCE EDI'l'OJl Ted While, ASSISTANT EDITOll Edword L. Ferman, MANAGING EDITOll Jtuiith Merril, BOOK EDITOll Robert P. Mills, CONSULTING EDITOR Tlut Magtniru of FaJIItuy 11t1d St:ietu:e Fktitn&, Volume 19, No. l, Whole No. 169, IM'M 1965. Pllblislled ,...,.ehly by Mercwr-, Press, Itu:., at 50- a co(>y. At~tiMal sMbscripliml $5.00; $5.50 i• Cat~ada and the Pa" America" Uni0t1; $6.00 in all other CDMfllries. PMbli catio" office, 10 Ferry Street, Catu:ord, N. H. Edieorial aftd get1eral mail shoMld be set1t to 341 Etut 53rd St., Nl!fiJ York, N. Y. 10022. Sectn&d CI<Us postage ~Jaid at Coftcord, N. H. Priated in U.S.A. C 1965 by Mercury Prrss, lflc. All~ rights, inclMding tratlslatitn&s ir~to otlutr langM~Jges, reserved. Submissitn&s ,...sl be accompanied by stamped, self-addressed eatJelopes; tlut Publisher us""'" no reqoruibili~ for reiN"' of ur~solicited mar~uscril>ls.