Chaos and Borges: a Map of Infinite Bifurcations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Experiment with Time Free

FREE AN EXPERIMENT WITH TIME PDF J.W. Dunne | 256 pages | 01 Apr 2001 | Hampton Roads Publishing Co | 9781571742346 | English | Charlottesville, VA, United States What | An Experiment with Time See what's new with book lending at the Internet Archive. Uploaded by artmisa on December 24, Search icon An illustration of a magnifying glass. User icon An illustration of a person's head and chest. Sign up Log in. Web icon An illustration of a computer application window Wayback Machine Texts icon An illustration of an open book. Books Video icon An illustration of two cells of a film strip. Video Audio icon An illustration of an audio speaker. Audio Software icon An illustration of a 3. Software Images icon An illustration An Experiment with Time two photographs. Images Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape Donate Ellipses icon An illustration of text ellipses. EMBED for wordpress. An Experiment with Time more? Advanced embedding details, examples, and help! My head An Experiment with Time flopped re the technical details but was astonished that here for the first time somebody has experienced and documented how I dream - Very pleased to have read it, I feel exonerated and recognised :. I enjoyed reading it. But I am not sure it is a book many will enjoy. Folkscanomy: A Library of Books. Additional Collections. An Experiment With Time : J.W. Dunne : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. -

Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Kevin Wilson Of Stones and Tigers; Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Pu Songling (1640-1715) (draft) The need to meet stones with tigers speaks to a subtlety, and to an experience, unique to literary and conceptual analysis. Perhaps the meeting appears as much natural, even familiar, as it does curious or unexpected, and the same might be said of meeting Pu Songling (1640-1715) with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), a dialogue that reveals itself as much in these authors’ shared artistic and ideational concerns as in historical incident, most notably Borges’ interest in and attested admiration for Pu’s work. To speak of stones and tigers in these authors’ works is to trace interwoven contrapuntal (i.e., fugal) themes central to their composition, in particular the mutually constitutive themes of time, infinity, dreaming, recursion, literature, and liminality. To engage with these themes, let alone analyze them, presupposes, incredibly, a certain arcane facility in navigating the conceptual folds of infinity, in conceiving a space that appears, impossibly, at once both inconceivable and also quintessentially conceptual. Given, then, the difficulties at hand, let the following notes, this solitary episode in tracing the endlessly perplexing contrapuntal forms that life and life-like substances embody, double as a practical exercise in developing and strengthening dynamic “methodologies of the infinite.” The combination, broadly conceived, of stones and tigers figures prominently in -

CS Lewis and JW Dunne

Volume 37 Number 2 Article 5 Spring 4-17-2019 The Last Serialist: C.S. Lewis and J.W. Dunne Guy W B Inchbald Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Inchbald, Guy W B (2019) "The Last Serialist: C.S. Lewis and J.W. Dunne," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 37 : No. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract C.S. Lewis was influenced yb Serialism, a theory of time, dreams and immortality proposed by J.W. Dunne. The closing chapters of the final Chronicle of Narnia, The Last Battle, are examined here. Relevant aspects of Dunne’s theory are drawn out and his known influence on the works of Lewis er visited. -

Edward F. Kelly, Chapter 1, Beyond Physicalism, Edward F

Supplemental web material for “Empirical Challenges to Theory Construction,” Edward F. Kelly, Chapter 1, Beyond Physicalism, Edward F. Kelly, Adam Crabtree, and Paul Marshall (Eds.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015. http://www.esalen.org/ctr-archive/bp © Robert Rosenberg 2015 All rights reserved A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON PRECOGNITION Robert Rosenberg Introduction Sidgwick, Eleanor 1888–1889: “On the Evidence for Premonitions” Myers, Frederic W. H. 1894–1895: “The Subliminal Self, Chapter VIII: The Relation of Supernormal Phenomena to Time;—Retrocognition” 1894–1895: “The Subliminal Self, Chapter IX: The Relation of Supernormal Phenomena to Time;—Precognition” Richet, Charles 1923: Thirty Years of Psychical Research 1931: L’Avenir et la Prémonition Osty, Eugene 1923: Supernormal Faculties in Man Dunne, J. W. 1927: An Experiment with Time Lyttelton, Edith 1937: Some Cases of Prediction Saltmarsh, H. F. 1934: “Report on cases of apparent precognition” 1938: Foreknowledge Rhine, L. E. 1954: “Frequency of Types of Experience in Spontaneous Precognition” 1955: “Precognition and Intervention” Stevenson, Ian 1970: “Precognition of Disasters” MacKenzie, Andrew 1974: Riddle of the Future Eisenbud, Jule 1982: Paranormal Foreknowledge Conclusions References Introduction Precognition—the appearance or acquisition of non-inferential information or impressions of the future—holds a special place among psi phenomena. Confounding as it does commonsense notions of time and causality, it is perhaps the most metaphysically offensive of rogue phenomena. In the past 130 years, a number of thoughtful investigators—none of them either naïve or foolish—have studied a growing collection incidents, all carefully vetted (excepting Rhine’s popularly solicited cases [below]). With the exception of the first author, Eleanor Sidgwick, who drew on a scant six years of evidence and found it tantalizing but insufficient, these investigators have repeatedly come to the generally reluctant conclusion that true precognition (or something identical to it with a different name) exists. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Art and Hyperreality Alfredo Martin-Perez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected]

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2014-01-01 Art and Hyperreality Alfredo Martin-Perez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Martin-Perez, Alfredo, "Art and Hyperreality" (2014). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 1290. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/1290 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HYPERREALITY & ART A RECONSIDERATION OF THE NOTION OF ART ALFREDO MARTIN-PEREZ Department of Philosophy APPROVED: Jules Simon, Ph.D. Mark A. Moffett, Ph.D. Jose De Pierola, Ph.D. ___________________________________________ Charles Ambler, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © By Alfredo Martin-Perez 2014 HYPERREALITY & ART A RECONSIDERATION OF THE NOTION OF ART by ALFREDO MARTIN-PEREZ Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Philosophy THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO December 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my daughters, Ruby, Perla, and Esmeralda, for their loving emo- tional support during the stressing times while doing this thesis, and throughout my academic work. This humble work is dedicated to my grandchildren. Kimberly, Angel, Danny, Freddy, Desiray, Alyssa, Noe, and Isabel, and to the soon to be born, great-grand daughter Evelyn. -

Experiments with Time Modernity Is Fascinated by Time. the Modern

Experiments with Time Modernity is fascinated by time. The modern world has gone through profound alterations in thinking about time. Charles Lyell’s formulation of geological ‘deep time’ in the 1830s laid the foundations for modern geology and palaeontology, and therefore for thinking about the archaic status of the Earth and its life. Without Deep Time, the temporal framework which Darwinian evolution required would have been inconceivable. In the 1840s, the imposition of a standardized national (and international) ‘Railway Time’ became necessary in order for trains to run on time: without a standard and comprehensible railway transport system, the global reach of the British Empire would have been significantly foreshortened. The postulation of a ‘fourth dimension’ in the 1880s directly informed Einstein’s theories of space-time. The discovery by Edwin Hubble in 1929 of galactic red shift, led to the big bang theory of the origin of the universe, and to speculations as to whether its expansion would increase indefinitely and thus lead, in accordance with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, to the inevitable heat death of the universe, black, frozen and remote; or, whether gravity would eventually overwhelm all other forces, making the universe contract back in on itself culminating in a satisfyingly apocalyptic ‘big crunch’. Philosophically and culturally, the work of Nordau and Spengler on forms of degeneration and decline, and Bergson on time- flux, and of McTaggart and Broad on the metaphysics of time are very significant. It is therefore understandable, perhaps, that in Time and Western Man (1927), Wyndham Lewis was to criticize what he saw as the Western intelligentsia’s misguided obsession with temporality. -

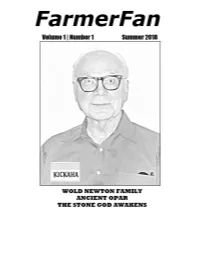

Farmerfan Volume 1 | Issue 1 |July 2018

FarmerFan Volume 1 | Issue 1 |July 2018 FarmerCon 100 / PulpFest 2018 Debut Issue Parables in Parabolas: The Role of Mainstream Fiction in the Wold Newton Mythos by Sean Lee Levin The Wold Newton Family is best known for its crimefighters, detectives, and explorers, but less attention has been given to the characters from mainstream fiction Farmer included in his groundbreaking genealogical research. The Swordsmen of Khokarsa by Jason Scott Aiken An in-depth examination of the numatenu from Farmer’s Ancient Opar series, including speculations on their origins. The Dark Heart of Tiznak by William H. Emmons The extraterrestrial origin of Philip José Farmer's Magic Filing Cabinet revealed. Philip José Farmer Bingo Card by William H. Emmons Philip José Farmer Pulp Magazine Bibliography by Jason Scott Aiken About the Fans/Writers Visit us online at FarmerFan.com FarmerFan is a fanzine only All articles and material are copyright 2018 their respective authors. Cover photo by Zacharias L.A. Nuninga (October 8, 2002) (Source: Wikimedia Commons) Parables in Parabolas The Role of Mainstream Fiction in the Wold Newton Mythos By Sean Lee Levin The covers to the 2006 edition of Tarzan: Alive and the 2013 edition of Doc Savage: His Apocalyptic Life Parables travel in parabolas. And thus present us with our theme, which is that science fiction and fantasy not only may be as valuable as the so-called mainstream of literature but may even do things that are forbidden to it. –Philip José Farmer, “White Whales, Raintrees, Flying Saucers” Of all the magnificent concepts put to paper by Philip José Farmer, few are as ambitious as his writings about the Wold Newton Family. -

Postmodern Or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation

Edna Aizenberg Postmodern or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation he list of “firsts” is well known by now: Borges, father of the New Novel, the nouveau roman, the Boom; Borges, forerunner T of the hypertext, early magical realist, proto-deconstructionist, postmodernist pioneer. The list is well known, but it may omit the most significant encomium: Borges, founder of literature after Auschwitz, a literature that challenges our orders of knowledge through the frac- tured mirror of one of the century’s defining events. Fashions and prejudices ingrained in several critical communities have obscured Borges’s role as a passionate precursor of many later intellec- tuals -from Weisel to Blanchot, from Amery to Lyotard. This omission has hindered Borges research, preventing it from contributing to major theoretical currents and areas of inquiry. My aim is to confront this lack. I want to rub Borges and the Holocaust together in order to unset- tle critical verities, meditate on the limits of representation, foster dia- logue between disciplines -and perhaps make a few sparks fly. A shaper of the contemporary imagination, Borges serves as a touch- stone for concepts of literary reality and unreality, for problems of knowledge and representation, for critical and philosophical debates on totalizing systems and postmodern esthetics, for discussions on cen- ters and peripheries, colonialism and postcolonialism. Investigating the Holocaust in Borges can advance our broadest thinking on these ques- tions, and at the same time strengthen specific disciplines, most par- ticularly Borges scholarship, Holocaust studies, and Latin American literary criticism. It is to these disciplines that I now turn. -

Perspectives on Borges' Library of Babel

Proceedings of Bridges 2015: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture Perspectives on Borges' Library of Babel CJ Fearnley Jeannie Moberly [email protected] [email protected] http://blog.CJFearnley.com http://Moberly.CJFearnley.com 240 Copley Road • Upper Darby, PA 19082 240 Copley Road • Upper Darby, PA 19082 Abstract This study builds on our Bridges 2012 work on Harmonic Perspective. Jeannie’s artwork explores 3D spaces with an intersecting plane construction. We used the subject of the remarkable “Universe (which others call the Library)” of Jorge Luis Borges. Our study explores the use of harmonic sequences and nets of rationality. We expand on our prior use of harmonics in Apollonian circles to a pencil of nonintersecting circles. Using matrix distortion and ambiguous direction in the multiple dimensions of a spiral staircase in the Library we break from harmonic measurements. We wonder about the contrasting perspectives of unimaginable finiteness and infiniteness. Figure 1 : Borges' Library of Babel (View of Apollonian Ventilation Shafts). Figure 2 : Borges' Library of Babel (Other View). Introduction In 1941, Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) published a short story The Library of Babel [2] that has intrigued artists, mathematicians, and philosophers ever since. The story plays with ideas of infinity, the very large but finite, the components of immensity, and periodicity. The Library consists of a vast number of hexagonal rooms each with the same number of books. Although each book is unique, each has the same number 443 Fearnley and Moberly of pages, lines, and characters. The librarians wander their whole lives through the labyrinth of rooms wondering about the nature of their Universe. -

Politics of the Name: on Borges's “El Aleph”

POLITICS OF THE NAME: ON BORGES’S “EL ALEPH” w Silvia Rosman Todo lenguaje es un alfabeto de símbolos cuyo ejercicio presupone un pasado que los interlocutores comparten J. L. Borges, “El aleph” n reaction to the vitriolic attacks on the inhuman and foreign nature of his writing, from the 1920s on Borges explores the I question of a common language and its implications for the concept of literature. Is there an authentic Argentinean language that would give rise to an equally authentic national literature? In “El idioma de los argentinos” (1927), Borges responds to this ques- tion by referring to a double particularity: “Dos influencias antagó- nicas entre sí militan contra un habla argentina. Una es la de quienes imaginan que esa habla ya está prefigurada en el arrabalero de los sainetes; otra es la de los casticistas o españolados que creen en lo cabal del idioma y en la impiedad o inutilidad de su refacción” (Idioma 136). Neither the localized slang of the Buenos Aires margins and its implied unity of place, nor the linguistic cohesion of a dic- tionary Spanish that no one speaks succeed in capturing the “voice” of the Spanish spoken in Argentina, crystallized as those two “lan- guages” are by their proper and definite meaning. Variaciones Borges 14 (2002) 8 SILVIA ROSMAN If a certain cultural nationalism imposed the normalizing parame- ters that a pedagogical notion of an Argentinean essence embodied (the continuity with Hispanic tradition, the notion of authenticity and uniqueness that would mark the nation’s autonomy), Borges finds in the performative use of language a certain linguistic com- monality: the “no escrito idioma argentino (…) diciéndonos,” where the intonation or inflexion of certain words can be heard. -

The-Circular-Ruins-Borges-Jorge

THE CIRCULAR RUINS miseroprospero.com/the-circular-ruins 31 March 2017 FRIDAY FICTION [3] A short story from Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges NO ONE saw him disembark in the unanimous night, no one saw the bamboo canoe sinking into the sacred mud, but within a few days no one was unaware that the silent man came from the South and that his home was one of the infinite villages upstream, on the violent mountainside, where the Zend tongue is not contaminated with Greek and where leprosy is infrequent. The truth is that the obscure man kissed the mud, came up the bank without pushing aside (probably without feeling) the brambles which dilacerated his flesh, and dragged himself, nauseous and bloodstained, to the circular enclosure crowned by a stone tiger or horse, which once was the colour of fire and now was that of ashes. The circle was a temple, long ago devoured by fire, which the malarial jungle had profaned and whose god no longer received the homage of men. The stranger stretched out beneath the pedestal. He was awakened by the sun high above. He evidenced without astonishment that his wounds had closed; he shut his pale eyes and slept, not out of bodily weakness but of determination of will. He knew that this temple was the place required by his invincible purpose; he knew that, downstream, the incessant trees had not managed to choke the ruins of another propitious temple, whose gods were also burned and dead; he knew that his immediate obligation was to sleep. Towards midnight he was awakened by the disconsolate cry of a bird.