Stories in Fabric: Quilting in the African American Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Textile Society of America Newsletter 21:3 — Fall 2009 Textile Society of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Newsletters Textile Society of America Fall 2009 Textile Society of America Newsletter 21:3 — Fall 2009 Textile Society of America Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews Part of the Art and Design Commons Textile Society of America, "Textile Society of America Newsletter 21:3 — Fall 2009" (2009). Textile Society of America Newsletters. 56. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsanews/56 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Newsletters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. T VOLUME 21 NUMBER 3 FALL, 2009 S A Conservation of Three Hawaiian Feather Cloaks by Elizabeth Nunan and Aimée Ducey CONTENTS ACRED GARMENTS ONCE to fully support the cloaks and and the feathers determined the worn by the male mem- provide a culturally appropriate scope of the treatment. 1 Conservation of Three Hawaiian bers of the Hawaiian ali’i, display. The museum plans to The Chapman cloak is Feather Cloaks S or chiefs, feather cloaks and stabilize the entire collection in thought to be the oldest in the 2 Symposium 2010: Activities and capes serve today as iconic order to alternate the exhibition collection, dating to the mid-18th Exhibitions symbols of Hawaiian culture. of the cloaks, therefore shorten- century, and it is also the most 3 From the President During the summer of 2007 ing the display period of any deteriorated. -

Antiracism and Restorative Justice in Classics Pedagogy

ANTIRACISM AND RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN CLASSICS PEDAGOGY: RACE, SLAVERY, AND THE FUNCTION OF LANGUAGE IN BEGINNING GREEK AND LATIN TEXTBOOKS by KELLY P. DUGAN (Under the Direction of RUTH HARMAN) ABSTRACT In Greek and Latin textbooks, verbal and visual discourses function together to construe Greco-Roman systems of enslavement. This dissertation is a critical discourse analysis of this construal based on the theories and methodologies of multicultural education and systemic functional linguistics. The findings illustrate how the linguistic resources of appraisal (feelings and character) and transitivity (agency and action) function to sanitize and normalize enslavement. The accompanying comparative analysis to 19th-century American discourses on enslavement demonstrates how the use of these linguistic resources are consistent across time and context. Therefore, although systems of enslavement in the Greco-Roman world were not race-based, the presentation of enslavement in Greek and Latin textbooks today engages in racist discourses that permeate the American education system. The eight chapters of this dissertation examine the context, theoretical framework, methodology, findings, and implications of the research. I begin with a discussion of the current context of Classics in America including its connection to White supremacy. I then narrow the scope by examining the situational context of Greek and Latin classrooms in America. At the center of this work is the analysis of Greek and Latin textbooks using multicultural education and systemic functional linguistics theory and methodology. After discussing the findings, I explore the pedagogical implications of this research. To conclude, the final chapter reflects on the research and offers a look toward future studies on enslavement discourses in American classrooms. -

Harriet Powers

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 21st Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 8th, 10:30 AM - 11:45 AM A Modern Mother: Harriet Powers Alyssa Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Johnson, Alyssa, "A Modern Mother: Harriet Powers" (2019). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2019/003/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. 1 A Modern Mother: Harriet Powers (1837-1911) [Catalogue Essay] In her conclusion to the widely-known essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists” Linda Nochlin declared, “Disadvantage may indeed be an excuse; it is not, however, an intellectual position.”1 This statement, while intended to be a charge for future contemporary artists and art historians alike, very well could have similarly been a salute to the artists of the past who worked from a place of disadvantage. The exhibition A Modern Mother: Harriet Powers (1837-1911) aims to identify one such woman, Harriet Powers, who lived nearly 150 years prior to the publication of Nochlin’s essay, in relationship with shift toward the avant-garde abstract art at the start of the modern era. The legacy left behind from the quilts of Harriet Powers, a freed slave from Georgia, is humble, but displays an example of great art coming from intersectional disadvantage. -

Proquest Dissertations

Stitching Together A Past To Create A Future: women, quilting groups and community in rural, southern New Brunswick By Danielle Sharp A Thesis Submitted to Saint Mary's University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts: Women and Gender Studies. (In partnership with Mount Saint Vincent University) February, 2010, Halifax, Nova Scotia © Danielle Sharp, 2010 Approved: Dr. Sandra Alfoldy, Supervisor Approved: Dr. Linda Christiansen-Ruffman, Examiner Approved: Dr. Louise Carbert, Reader Date: 19 February 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'gdition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-64857-5 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-64857-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliothdque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Finding Aid for Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Collection, Michigan State University Museum

1 Cuesta Benberry Quilt Research Collection Finding Aid for Cuesta Benberry African and African American Quilt and Quilt History Collection, Michigan State University Museum Contents Collection Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Collection numbers (DACS 2.1; MARC 099): ............................................................................................. 3 Collection title (DACS 2.3; MARC 245): ..................................................................................................... 3 Dates (DACS 2.4; MARC 245): ................................................................................................................... 3 Size (DACS 2.5; MARC 300): ...................................................................................................................... 3 Creator/Collector (DACS 2.6 & Chapter 9; MARC100, 10, 245, 600): ....................................................... 3 Acquisition info. (DACS 5.2; MARC 584): .................................................................................................. 3 Accruals (DACS 5.4; MARC 584): ............................................................................................................... 4 Custodial history (DACS 5.1; MARC 561): ................................................................................................. 4 Language (DACS 4.5; MARC 546): ............................................................................................................ -

FEMMAGE and the DIY MOVEMENT: FEMINISM, CRAFTY WOMEN, and the POLITICS of GENDER PERFORMANCE Rosemary L

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2016 FEMMAGE AND THE DIY MOVEMENT: FEMINISM, CRAFTY WOMEN, AND THE POLITICS OF GENDER PERFORMANCE Rosemary L. Sallee Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Recommended Citation Sallee, Rosemary L.. "FEMMAGE AND THE DIY MOVEMENT: FEMINISM, CRAFTY WOMEN, AND THE POLITICS OF GENDER PERFORMANCE." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/48 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Rosemary L. Sallee Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication. Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Rebecca Schreiber, Ph.D. Associate Professor, American Studies, University of New Mexico Michael L. Trujillo, Ph.D. Associate Professor, American Studies, University of New Mexico Ronda Brulotte, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Anthropology, University of New Mexico Joyce Ice, Ph.D. Director, Museum of Art, West Virginia University ii FEMMAGE AND THE DIY MOVEMENT: FEMINISM, CRAFTY WOMEN, AND THE POLITICS OF GENDER PERFORMANCE BY ROSEMARY L. SALLEE A.B. American Culture, Vassar College, 1992 M.A. American Studies, University of New Mexico, 2003 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2016 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must first thank my stalwart committee, Rebecca Schreiber, Michael Trujillo, Ronda Brulotte and Joyce Ice, for your endurance, patience, and insight through this journey. -

Discover Something Different

Fall 2020 Discover something different. Registration opens Sep 3 | Classes start the week of Sep 28 GREETINGS Welcome to Minneapolis Community Education! Our mission is to engage youth and adults in community-driven learning and enrichment opportunities. Our programs, Adult Enrichment, Minneapolis Kids, Adult Education and Youth Enrichment embrace these beliefs: • Education is a lifelong process; • Everyone in the community - individuals, businesses, public and private agencies — shares responsibility for educating all members of the community; and • Citizens have a right and a responsibility to be involved in determining community needs, identifying community resources, and linking those needs and resources to their community. We invite you to get involved. Take a class, share your ideas with a focus group, join an advisory committee, teach a class or partner with us. Due to COVID-19, Minneapolis Community Education’s fall programs will look different this year. We’ve taken steps to make sure your experience is as enjoyable as it’s always been and are offering over 300 adult enrichment classes online! See page 27 for some socially distant outside options, too. We also will be offering a wide array of other youth and adult options Like you, we wish circumstances allowed us to meet in person, but as we learned this spring and summer, we can continue lifelong learning, share common passions, and grow our community together— from a distance. Table of Contents Life & Learning Academic Enrichment ....................................... 5 Writing ............................................................... 7 Business & Consumer ........................................ 8 Real Estate & Personal Development ..............10 Computers & Technology ................................11 30 Trips & Tours ....................................................16 Hobbies & Skills 11 Cooking ........................................................... 12 Hobby & Leisure ............................................. -

Down Time by Leslie M

Time OOOn the An Arrrt of RRRetetetrrreateateat Finding Down Time by Leslie M. Wilson William Sidney Mount Farmers Nooning, 1836 A black man reclines on a low haystack sleeping in the hot sun while a child tickles his ear with a feather. Three white male figures occupy the immediate foreground in various forms of repose and quiet activity. The tools of their work are at hand, but these laborers are firmly in the world of a mid-day break in William Sidney Mount’s Farmers Nooning (1836). Yet, as Elizabeth Johns has persuasively interpreted Mount’s famous nineteenth-century painting, the composition’s allegor- ical dimensions suggest a far more charged significance for the black man’s sleep and the child’s prank.1 Through an anti-aboli- tionist lens, Johns posits that the “ear tickling” child who wears a tam-o’-shanter represents those who sought to ill-advisedly stir up black people, to wake them up in 1830s America (as if they did not possess their own ample motivations). If that is the case, rousing the sleeping figure is akin to the act of consciousness raising. Outstretched in resplendent, indulgent sleep—open to accusations of laziness or the even more racially charged designation of “shiftlessness”—the dormant man has the potential to be all at once peaceful and dangerous. I quietly meditated on Mount’s painting as the students of “Exhibition in Practice I” shaped the concept behind this exhibition. It then found its way into class discussion through Cameron Robertson (AB ’19), who suggested this as an artwork to consider for our exhibition Down Time: On the Art of Retreat. -

Recommended Trade Books for Adult Literacy Programs: Part Three. INSTITUTION Kent State Univ., OH

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 414 510 CE 075 499 AUTHOR Sapin, Connie; Bloem, Pat; Padak, Nancy TITLE Recommended Trade Books for Adult Literacy Programs: Part Three. INSTITUTION Kent State Univ., OH. Ohio Literacy Resource Center. SPONS AGENCY National Inst. for Literacy, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1997-11-00 NOTE 93p.; For part one, see ED 381 672. For part two, see CE 071 922. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; High School Equivalency Programs; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Materials; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS General Educational Development Tests ABSTRACT This supplement to an annotated bibliography describes nearly 100 books that are appropriate for use with adult learners. Some of the titles in this supplement are books best used for independent reading, but most have strong instructional ties. The supplement contains many books that can be useful in General Educational Development (GED) instruction, even for learners whose achievement may be at pre-GED levels. Each one-page summary lists bibliographical information, including ordering information, a brief summary, and themes related to the book and a GED descriptor, if appropriate. A "teaching ideas" section on each page offers general instructional suggestions, writing or discussion topics, and, in some instances, related titles. This supplement also includes a "Thematic Collections Index" for all three parts of the "Recommended Trade Books" series. Books chosen for this publication have bec: re_d t .7.t. least three readers and are rated by "W" (whole-hearted approval) or "G" (guidance). (KC) ******************************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Author Last Prefix

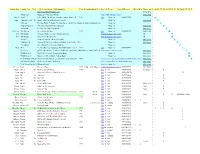

Author_First - Author_Last Prefix - Title -- Last Update 2003-August-16 Year SettingMulticultural ThemesAmazonLvl Theme Own i SBN (no i ) AR LevelAR ptsComments RecAtwellBourque (A)ChicagoCalif (B)Frstbrn24 CDCEGirls (D)MacKnight (F)NewberyOaklandPat RiefRAllison USDTCY (P)W X * * http://www.WelchEnglish.com/ i Merged List of0 Recommended and Favorite Books for Adolescent Readers * * About.com About.com - Historical Fiction http://childrensbooks.about.com/cs/historicalfiction/i http://childrensbooks.about.com/cs/historicalfiction/0 Nancie * Atwell In the Middle: New Understandings About Writing, Reading,1998 and Learning http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0867093749/timstore06-20* * Book List i 0867093749 1 A Louise * Bourque (and GwenThe Johnson)Book Ladies' List of Students' Favorites * * Book List i http://www.qesnrecit.qc.ca/ela/refs/books.htm1 B * * Chicago Chicago Public Schools - Reading List (recommended books for high school students) * * Book List i 1 C * * Dept of Ed, Calif * Reading List for California Students * * Book List i http://www.cde.ca.gov/literaturelist/litsearch.asp1 D * * Frstbrn24 Reading List 2002: Firstbrn24 * * Book List i http://pages.ivillage.com/frstbrn24/readinglist2002.htm1 F Kathleen * G - Odean Great Books for Girls 1997 http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0345450213/timstore06-20* * Book List 1 i 0345450213 Updated 20021 edition also availableG Eric * MacKnight Favourite Books as chosen by my students http://homepage.mac.com/ericmacknight/favbks.htmli UK 1 M Eric * MacKnight Independent Reading -

Anna Von Mertens Discipline: Visual Arts (Quilting)

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Needlework Subject: Anna Von Mertens Discipline: Visual Arts (Quilting) SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE RESOURCES – TEXTS RESOURCES – WEB SITES BAY AREA RESOURCES - CLASSES BAY AREA RESOURCES – TEXTILE COLLECTIONS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................8 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 10 Quilts in the MATRIX project series by Anna Von Mertens on exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum in 2003. Reprinted with permission from http://www.annavonmertens.com. Photo: Jean‐Michel Addor. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES Needlework To enable students to ‐ Understand the development of personal works of SUBJECT art and their relationships to social themes and Anna Von Mertens ideas, abstract concepts, and the history of art. Develop basic observational drawing and/or GRADE RANGES painting skills. K‐12 & Post‐secondary Develop visual, written, listening and speaking skills through looking -

Africana Studies Student Research Conference 2019 Program

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 21st Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 8th, 8:30 AM - 3:00 PM Africana Studies Student Research Conference 2019 Program Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the Africana Studies Commons Bowling Green State University, "Africana Studies Student Research Conference 2019 Program" (2019). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 4. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2019/posters/4 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. THE 21ST ANNUAL AFRICANA STUDIES STUDENT RESEARCH CONFERENCE & LUNCHEON Emerging Perspectives in Africana Studies Friday, February 8, 2019 BOWEN-THOMPSON STUDENT UNION • BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY THE 21ST ANNUAL AFRICANA STUDIES MORNING AGENDA 8:30–9:00 Tea & coffee BTSU Ballroom, Side B 9:00–10:15 PANEL 1: INTERSECTIONS OF RACE BTSU Ballroom, Side B Moderator: Ivan Gusev Johnson (MA student, Literary & Textual Studies/Spanish, BGSU) PANELISTS: Joseph Z. Johnson (Undergrad, World Music and Saxophone Performance, BGSU) “Blended Styles of African American Folk Music” Sarah Bishop (PhD candidate, Ethnomusicology, The Ohio State University) “‘Unite Yourselves in the Name of Anywaa’: Music and Anywaa Ethnic Identity in Gambella, Ethiopia” Jasmine Mitchell (Undergrad, East Asian Studies, Oberlin College) “Racism, Prejudice, and Democratization: The Westernization of Japan Under U.S. Occupation, 1945-52” PANEL 2: EDUCATION Sky Bank Room (201) Moderator: Eva-Maria Trinkaus (Austria: Fulbright, PhD candidate, American Literature) PANELISTS: Lyndah Naswa Wasike (MA student, Cross-Cultural & International Education [MACIE], BGSU) “Giving a Voice to the Voiceless and Women’s Education in Kenya” Ethan W.