On the Non-Existence of Cartesian Linguistics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

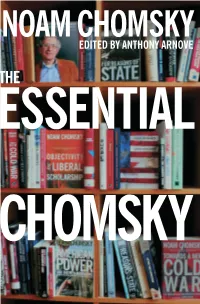

Essential Chomsky

CURRENT AFFAIRS $19.95 U.S. CHOMSKY IS ONE OF A SMALL BAND OF NOAM INDIVIDUALS FIGHTING A WHOLE INDUSTRY. AND CHOMSKY THAT MAKES HIM NOT ONLY BRILLIANT, BUT HEROIC. NOAM CHOMSKY —ARUNDHATI ROY EDITED BY ANTHONY ARNOVE THEESSENTIAL C Noam Chomsky is one of the most significant Better than anyone else now writing, challengers of unjust power and delusions; Chomsky combines indignation with he goes against every assumption about insight, erudition with moral passion. American altruism and humanitarianism. That is a difficult achievement, —EDWARD W. SAID and an encouraging one. THE —IN THESE TIMES For nearly thirty years now, Noam Chomsky has parsed the main proposition One of the West’s most influential of American power—what they do is intellectuals in the cause of peace. aggression, what we do upholds freedom— —THE INDEPENDENT with encyclopedic attention to detail and an unflagging sense of outrage. Chomsky is a global phenomenon . —UTNE READER perhaps the most widely read voice on foreign policy on the planet. ESSENTIAL [Chomsky] continues to challenge our —THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW assumptions long after other critics have gone to bed. He has become the foremost Chomsky’s fierce talent proves once gadfly of our national conscience. more that human beings are not —CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT, condemned to become commodities. THE NEW YORK TIMES —EDUARDO GALEANO HO NE OF THE WORLD’S most prominent NOAM CHOMSKY is Institute Professor of lin- Opublic intellectuals, Noam Chomsky has, in guistics at MIT and the author of numerous more than fifty years of writing on politics, phi- books, including For Reasons of State, American losophy, and language, revolutionized modern Power and the New Mandarins, Understanding linguistics and established himself as one of Power, The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human the most original and wide-ranging political and Nature, On Language, Objectivity and Liberal social critics of our time. -

Skepticism and Pluralism Ways of Living a Life Of

SKEPTICISM AND PLURALISM WAYS OF LIVING A LIFE OF AWARENESS AS RECOMMENDED BY THE ZHUANGZI #±r A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PHILOSOPHY AUGUST 2004 By John Trowbridge Dissertation Committee: Roger T. Ames, Chairperson Tamara Albertini Chung-ying Cheng James E. Tiles David R. McCraw © Copyright 2004 by John Trowbridge iii Dedicated to my wife, Jill iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In completing this research, I would like to express my appreciation first and foremost to my wife, Jill, and our three children, James, Holly, and Henry for their support during this process. I would also like to express my gratitude to my entire dissertation committee for their insight and understanding ofthe topics at hand. Studying under Roger Ames has been a transformative experience. In particular, his commitment to taking the Chinese tradition on its own terms and avoiding the tendency among Western interpreters to overwrite traditional Chinese thought with the preoccupations ofWestern philosophy has enabled me to broaden my conception ofphilosophy itself. Roger's seminars on Confucianism and Daoism, and especially a seminar on writing a philosophical translation ofthe Zhongyong r:pJm (Achieving Equilibrium in the Everyday), have greatly influenced my own initial attempts to translate and interpret the seminal philosophical texts ofancient China. Tamara Albertini's expertise in ancient Greek philosophy was indispensable to this project, and a seminar I audited with her, comparing early Greek and ancient Chinese philosophy, was part ofthe inspiration for my choice ofresearch topic. I particularly valued the opportunity to study Daoism and the Yijing ~*~ with Chung-ying Cheng g\Gr:p~ and benefited greatly from his theory ofonto-cosmology as a means of understanding classical Chinese philosophy. -

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

How to Represent Human Behavior and Decision Making in Earth System Models?

Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., doi:10.5194/esd-2017-18, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Syst. Dynam. Discussion started: 2 March 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. How to represent human behavior and decision making in Earth system models? A guide to techniques and approaches Finn Müller-Hansen1,2, Maja Schlüter3, Michael Mäs4, Rainer Hegselmann5, 6, Jonathan F. Donges1,3, Jakob J. Kolb1,2, Kirsten Thonicke1, and Jobst Heitzig1 1Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, Telegrafenberg A31, 14473 Potsdam, Germany 2Department of Physics, Humboldt University Berlin, Newtonstraße 15, 12489 Berlin, Germany 3Stockholm Resilience Center, Stockholm University, Kräftriket 2B, 114 19 Stockholm, Sweden 4Department of Sociology and ICS, University of Groningen, Grote Rozenstraat 31, 9712 TG Groningen, The Netherlands 5Frankfurt School of Finance & Manangement, Sonnemannstraße 9-11 60314 Frankfurt am Main, Germany 6Bayreuth Research Center for Modeling and Simulation, Bayreuth University, Universitätsstrasse 30, 95440 Bayreuth, Germany Correspondence to: Finn Müller-Hansen ([email protected]) Abstract. In the Anthropocene, humans have a critical impact on the Earth system and vice versa, which can generate complex feedback processes between social and ecological dynamics. Integrating human behavior into formal Earth System Models (ESMs), however, requires crucial modeling assumptions about actors and their goals, behavioral options and decision rules, as well as modeling decisions regarding human social interactions and the aggregation of individuals’ behavior. In this tutorial 5 review, we compare existing modeling approaches and techniques from different disciplines and schools of thought dealing with human behavior at various levels of decision making. Providing an overview over social-scientific modeling approaches, we demonstrate modelers’ often vast degrees of freedom but also seek to make modelers aware of the often crucial consequences of seemingly innocent modeling assumptions. -

A Naturalist Reconstruction of Minimalist and Evolutionary Biolinguistics

A Naturalist Reconstruction of Minimalist and Evolutionary Biolinguistics Hiroki Narita & Koji Fujita Kinsella & Marcus (2009; K&M) argue that considerations of biological evo- lution invalidate the picture of optimal language design put forward under the rubric of the minimalist program (Chomsky 1993 et seq.), but in this article it will be pointed out that K&M’s objection is undermined by (i) their misunderstanding of minimalism as imposing an aprioristic presumption of optimality and (ii) their failure to discuss the third factor of language design. It is proposed that the essence of K&M’s suggestion be reconstructed as the sound warning that one should refrain from any preconceptions about the object of inquiry, to which K&M commit themselves based on their biased view of evolution. A different reflection will be cast on the current minima- list literature, arguably along the lines K&M envisaged but never completed, converging on a recommendation of methodological (and, in a somewhat unconventional sense, metaphysical) naturalism. Keywords: evolutionary/biological adequacy; language evolution; metho- dological/metaphysical naturalism; minimalist program; third factor of language design 1. Introduction A normal human infant can learn any natural language(s) he or she is exposed to, whereas none of their pets (kittens, dogs, etc.) can, even given exactly the same data from the surrounding speech community. There must be something special, then, to the genetic endowment of human beings that is responsible for the emer- gence of this remarkable linguistic capacity. Human language is thus a biological object that somehow managed to come into existence in the evolution of the hu- man species. -

The Language Faculty – Mind Or Brain?

The Language Faculty – Mind or Brain? TORBEN THRANE Aarhus University, School of Business, Denmark Artiklens sigte er at underkaste Chomskys nyskabende nominale sammensætning – “the mind/brain” – en nøjere undersøgelse. Hovedargumentet er at den skaber en glidebane, således at det der burde være en funktionel diskussion – hvad er det hjernen gør når den behandler sprog? – i stedet bliver en systemdiskussion – hvad er den interne struktur af den menneskelige sprogevne? Argumentet søges ført igennem under streng iagttagelse af de kognitive videnskabers opfattelse af information og repræsentation, specielt som forstået af den amerikanske filosof Frederick I. Dretske. 1. INTRODUCTION Cartesian dualism is dead, but the central problems it was supposed to solve persist: What kinds of substances exist? Are bodily things (only) physical, mental ‘things’ (only) metaphysical? How is the mental related to the physical? Although “we are all materialists now”, such questions still need answers, and they still need answers from within realist and naturalist bounds to count as scientific. Linguistics is a discipline that may be expected to contribute with answers to such questions. No one in their right mind would deny that our ability to acquire and use human language is lodged between our ears – inside our heads. That is, in our brains and/or minds. In some quarters it has been customary for the past 50 odd years or so to regard this ability as a distinct and dedicated cognitive ability on a par with our abilities to see (vision) or to keep our balance (equilibrioception), and to refer to it as the Human Language Faculty (HLF). This has been the axiomatic starting point for the development of main stream generative linguistics as founded by Chomsky in 1955 in what I shall refer to as ‘Chomsky’s programme’. -

The Role of Affect in Language Development∗

The Role of Affect in Language Development∗ Stuart G. SHANKER and Stanley I. GREENSPAN BIBLID [0495-4548 (2005) 20: 54; pp. 329-343] ABSTRACT: This paper presents the Functional/Emotional approach to language development, which explains the process leading up to the core capacities necessary for language (e.g., pattern-recognition, joint attention); shows how this process leads to the formation of internal symbols; and how it shapes and is shaped by the child’s development of language. The heart of this approach is that, through a series of affective transfor- mations, a child develops these core capacities and the capacity to form meaningful symbols. Far from be- ing a sudden jump, the transition from pre-symbolic communication to language is enabled by the advances taking place in the child’s affective gesturing. Key words: Functional/Emotional hypothesis; affective transformations; usage-based linguistics; pattern-recognition; joint attention; learning-based interactions; nativism; autism 1. The F/E View of Language Development Chomsky began Cartesian Linguistics with the following quotation from Whitehead’s Science and the Modern World: A brief, and sufficiently accurate, description of the intellectual life of the European races during the succeeding two centuries and a quarter up to our own times is that they have been living upon the accumulated capital of ideas provided for them by the genius of the seventeenth cen- tury (Chomsky 1967). Chomsky was certainly right: both in regards to the accuracy of Whitehead’s ob- servation, and in regards to the significance of this outlook for Chomsky’s whole ap- proach to language acquisition. -

New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind Noam Chomsky Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521651476 - New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind Noam Chomsky Frontmatter More information New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind This book is an outstanding contribution to the philosophical study of language and mind, by one of the most influential thinkers of our time. In a series of penetrating essays, Noam Chomsky cuts through the confusion and prejudice which has infected the study of language and mind, bringing new solutions to traditional philosophical puzzles and fresh perspectives on issues of general interest, ranging from the mind–body problem to the unification of science. Using a range of imaginative and deceptively simple linguistic ana- lyses, Chomsky argues that there is no coherent notion of “language” external to the human mind, and that the study of language should take as its focus the mental construct which constitutes our knowledge of language. Human language is therefore a psychological, ultimately a “biological object,” and should be analysed using the methodology of the natural sciences. His examples and analyses come together in this book to give a unique and compelling perspective on language and the mind. is Institute Professor at the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Chomsky has written and lectured extensively on a wide range of topics, including linguistics, philosophy, and intellectual history. His main works on linguistics include: Syntactic Structures; Current Issues in Linguistic Theory; Aspects of the Theory of Syntax; Cartesian Linguistics; Sound Pattern of English (with Morris Halle); Language and Mind; Reflections on Language; The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory; Lec- tures on Government and Binding; Modular Approaches to the Study of the Mind; Knowledge of Language: its Nature, Origins and Use; Language and Problems of Knowledge; Generative Grammar: its Basis, Development and Prospects; Language in a Psychological Setting; Language and Prob- lems of Knowledge; and The Minimalist Program. -

CHOMSKY, Noam Avram (1928- ) Forthcoming in the Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, 1860-1960 Ed., Ernest Lepore, Thoemmes Press, 2004

CHOMSKY, Noam Avram (1928- ) Forthcoming in the Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers, 1860-1960 ed., Ernest LePore, Thoemmes Press, 2004. Noam Chomsky was born to Dr. William (Zev) Chomsky and Elsie Simonofsky in Philadelphia on December 7, 1928. His father emigrated to the United States from Russia. William was an eminent scholar, author of the study Hebrew, the Eternal Language (1957), as well as numerous other works on the history and teaching of Hebrew. Noam entered the University of Pennsylvania in 1945. There he came in contact with Zelig Harris, a prominent linguist and the founder of the first linguistics department in the United States (at the University of Pennsylvania). In 1947 Chomsky decided to major in linguistics, and in 1949 he began his graduate studies in that field. His BA honor’s thesis Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew (1949, revised as an MA thesis in 1951) contains several ideas that foreshadow Chomsky’s later work in generative grammar. In 1949 he married the linguist Carol Schatz. During the years 1951 to 1955 Chomsky was a Junior Fellow of the Harvard University Society of Fellows, where he completed his PhD dissertation entitled Transformational Analysis (1955; published as part of The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory in 1975). Chomsky received a faculty position at MIT in 1955 and he has been teaching there ever since. In 1961 he was appointed full professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics; the graduate program in linguistics began the same year. In 1966 he was appointed Ferrari Ward Professor of Linguistics. In 1976, the linguistics and philosophy programs at MIT were merged and the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy was created; this has been Chomsky’s home department ever since. -

Noam Chomsky Written by E-International Relations

Interview - Noam Chomsky Written by E-International Relations This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. Interview - Noam Chomsky https://www.e-ir.info/2014/02/03/interview-noam-chomsky/ E-INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, FEB 3 2014 Noam Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He received his PhD in linguistics in 1955 from the University of Pennsylvania. From 1951 to 1955, Chomsky was a Junior Fellow of the Harvard University Society of Fellows. The major theoretical viewpoints of his doctoral dissertation appeared in the monographSyntactic Structure in 1957. This formed part of a more extensive work,The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory, circulated in mimeograph in 1955 and published in 1975. Chomsky joined the staff of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1955 and in 1961 was appointed full professor. In 1976 he was appointed Institute Professor in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy. Chomsky has lectured at many universities in the US and abroad, and is the recipient of numerous honorary degrees and awards. He has written and lectured widely on linguistics, philosophy, intellectual history, contemporary issues, international affairs, and U.S. foreign policy. Among his more recent books are,New Horizons in the Study of Language and Mind; On Nature and Language; The Essential Chomsky; Hopes and Prospects; Gaza in Crisis; How the World Works;9-11: Was There an Alternative; Making the Future: Occupations, Interventions, Empire, and Resistance; The Science of Language; Peace with Justice: Noam Chomsky in Australia; Power Systems; and On Western Terrorism: From Hiroshima to Drone Warfare (with Andre Vltchek). -

Philosophy: Third Edition Robert Audi & Paul Audi Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-01505-0 - The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy: Third Edition Robert Audi & Paul Audi Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE DICTIONARY OF PHILOSOPHY THIRD EDITION This is the most comprehensive dictionary of philosophical terms and thinkers available in English. Previously acclaimed as the most author- itative and accessible dictionary of philosophy in any language, it has been widely translated and has served both professional philosophers and students of philosophy worldwide. Written by a team of more than 550 experts – including more than 100 new to this third edition – the dictionary contains approximately 5,000 entries ranging from short definitions to full-length articles. It concisely defines terms, concretely illustrates ideas, and informatively describes philosophers. It is designed to facilitate the understanding of philosophy at all levels and in all fields. Key features of this third edition: Some 500 new entries covering both Eastern and Western philosophy, as well as individual countries such as China, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain Increased coverage of such growing fields as ethics and philosophy of mind Scores of new intellectual portraits of leading contemporary thinkers Wider coverage of Continental philosophy Dozens of new concepts in cognitive science and other areas Enhanced cross-referencing to add context and to increase under- standing Expansions of both text and index to facilitate research and browsing Robert Audi is John A. O’Brien Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame. He is the author of numerous books and articles. His recent books include Moral Perception (2013); Democratic Authority and the Separation of Church and State (2011); Rationality and Religious Commitment (2011); Epistemology: A Contemporary Introduction to the Theory of Knowledge (2010); and Moral Value and Human Diversity (2007). -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Destructive realism: Metaphysics as the foundation of natural science Rowbottom, Darrell Patrick How to cite: Rowbottom, Darrell Patrick (2004) Destructive realism: Metaphysics as the foundation of natural science, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2824/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk DESTRUCTIVE REALISM: METAPHYSICS AS THE FOUNDATION OF NATURAL SCIENCE DARRELL PATRICK ROWBOTTOM THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD IN PHILOSOPHY, OF THE UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM 2004 ABSTRACT This thesis has two philosophical positions as its targets. The first is 'scientific realism' of the form defended by Boyd, (the early) Putnam, and most recently Psillos. The second is empiricism in the vein of Mill, Mach, Ayer, Carnap, and Van Fraassen. My objections to both have a rather Popperian flavour. For I argue that 'confirmation' is a misnomer, that so-called 'ampliative inferences' are heuristics at best, and that naturalism and subjectivism are regressive doctrines.